Contracts Law Outline: Formation, Consideration, & Bargaining

advertisement

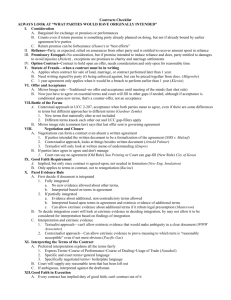

Contracts Outline – Hadfield, Fall 2005 - Elements to the existence of a contract: (1) A promise or promises, AND (2) Enforcement Contract Law: wants to enforce contracts that people want to be in and not enforce the ones that they don’t want to be in. Contracts are consensual agreements. 2 types of K: (3) Unilateral K: a K where only one party makes a promise and consideration is the promise’s performance in return for the promisor’s promise. promise performance of promise (4) Bilateral K: Consideration is the promisee’s promise to perform; each party’s bargained-for promise must be legally sufficient consideration for its counterpromise. promise promise ((What law applies?)) 1) Common Law: governs contracts for services 2) The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC): governs contracts for the sale of goods (movable objects) a) Has special rules applying to merchants: people who regularly deal with the sale of goods. ((Was a K formed?)) 1) Formation a) Mutual Assent – Intent to contract ((see Bargaining Process below)) i) **What it is reasonable to understand the parties to have agreed to?** i) An agreement is formed when there is a meeting of the minds between the parties on all of the essential terms of the proposed transaction ii) Objective Theory of Contracts: Must determine what the reasonable interpretation of the words/conduct of the parties were in the context of the contract iii) Offer/Acceptance as mechanisms for mutual assent (a) Is it reasonable to interpret the offer as an intent to be bound? (b) Is it reasonable to interpret the acceptance as an intent to be bound? Lucy v. Zehmer (Sup. Ct. of VA – 1954): An agreement can only be judged by the expressions of the intentions that are communicated, not mental assent, so a person cannot claim it was a joke when the words said would make a reasonable person believe the agreement was real. (Zehmer claimed to be drunk – the court didn’t buy it). Promise of land Promise of $50,000. Leonard v. Pepsico (S.D.NY – 1999): The commercial was an advertisement, not an offer. The general attitude of the commercial would not cause a reasonable person to conclude that the fighter planes were really being given away in the promotion (that the ad was an offer). b) Consideration i) Must be bargained for ii) Additional types of consideration: (1) Benefit - a promise is legally binding if it is given in return for some benefit which is rendered/or to be rendered, to the promisor. (2) Detriment – a promise is binding if the promisee incurs a detriment by reliance upon it Kirksey v. Kirksey (Sup. Ct. of AL – 1845): Brother-in-law told the widow to move her and her children to come live with him, and she could raise her family and tend land there. Court said this was not an enforceable promise because there is no bargain or deal. – Just a gratuitous promise with no consideration. Hamer v. Sidway (Ct. of Apps. NY – 1891): Uncle promised his nephew to give him $5,000 if he did not drink any liquor, smoke, or gamble until he turned 21. Court said that the nephew had the freedom of action to do these things and he gave up that freedom so there was consideration for the exchange. Nephew was giving up a “right” Promise of $5,000 iii) No consideration (1) Gift/Gratuitous Promise – no exchange, no consideration (2) Nominal Consideration – “in name only” – what is given is so small in value in exchange for what is being received that no reasonable person would make such a one-sided bargain (basically make it an enforceable contract without a bargain) (3) Illusory Consideration – where the promise on one side is not a promise that constrains the person on that side. Ex. “Pay me $10 and I will walk to the corner if I feel like it” (Might not feel like it). Ex2. “We will promise to sell it to you, if we decide to.” – must be some constraint. (4) Past Consideration – not consideration because it is not given in exchange for a promise (5) Moral Consideration – not consideration because it is just a promise made in recognition of moral obligation. iv) Substitutes/Alternatives to Consideration – Can enforce promises without a bargained-for legal detriment (1) Promissory Estoppel (§90): reliance (a) Promisor made a promise (b) Promisor could reasonably foresee that the promisee might rely on it (c) Promisee relied on it to his substantial detriment (d) And injustice can be avoided only by enforcement Katz v. Danny Dare (Ct. of Apps. Missouri – 1980): Katz worked at Danny Dare and left work when he was offered a pension plan. The promise was made to him. It was foreseeable to Dare that Katz would rely on this promise when he retired. Katz relied on this promise and retired (incurring a detriment of $10K in earnings a year. Now, Katz cannot engage in a full-time job to return the earnings because he is 70 years old – only avoid injustice by enforcement. (2) Promissory Restitution (§86: A promise made for a benefit already received is binding unless the benefit is a gift or the value is disproportionate) (a) The promisee conferred a material and substantial benefit, AND (b) That benefit was personally received by the promisor Webb v. McGowin (Ct. of Apps. AL – 1935): Webb saved McGowin from death or grievous harm when he diverted the direction of a falling block by harming himself, and McGowin agreed to pay him for the service rendered. “Where the promisee cares for, improves, and preserves the property of the promisor, though done without his request, it is sufficient consideration for the subsequent agreement to pay for the service, because of the material benefit received.” c) Sufficient Definiteness i) The terms must be certain – no ambiguity ii) Court must have a basis for judging breach and remedy. iii) Look at terms of the contract and perhaps at subsequent conduct that might support. ((What goes into making a K? – The Bargaining Process)) 1) Offer and Acceptance are tools for establishing the intent to enter a contract and the bargain for a contract (§22) i) An offer is not a contract, and there is no obligation, until there is an appropriate acceptance. ii) The offer must be received to be accepted – the acceptance must be a response to the offer. a) The acceptance must comply with the terms of the offer (§58) i) Mirror Image Rule – acceptance must mirror the offer, or it might be a counteroffer b) OFFER (§24): the manifestation of the willingness to enter a bargain. Offer is enough for the offeree to show intention to sell on the part of the offeror. The offeror is the Master of the Offer. c) ACCEPTANCE (§50): the manifestation of assent to the terms proposed in the offer. As soon as acceptance is shown, the offeror intends to be bound. i) Silence may be acceptance based on context d) Mailbox Rule (§63): acceptance is effective upon dispatch, not receiving – this rule applies when no other method is stipulated in the contract. Lonergan v. Scolnick (Ct. App. CA – 1954): P wants to show that a contract for 40 acres in Joshua Tree for $2500 came into existence. There was an ad placed in the paper, an inquiry, further information, verification of information, D warns P to act fast and sells to someone else, P enters into escrow but too late. Trial court says an offer was made, but by the terms, the acceptance should have been faster and P did not reply quickly enough. Appellate Ct says that no offer was made – just an intention to weigh interest, not intention to offer. Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. (Ct. App England – 1893): D ran an ad that promised to pay 100 pounds to anyone who contracted the flu after inhaling the smoke ball 3 times a day for 2 weeks. P accepted by performance. Court says as long as the offer hasn’t been revoked, offeror can get the notice of acceptance at the same time as the notice of performance. Davis v. Jacoby (Sup. Ct. CA – 1934): The Whiteheads were sick, and called their niece and her husband to come and take care of them. In exchange Mr. WH told them that they would get a large amount of money from their wills. The Court, reluctant to accept an offer as an offer for a unilateral contract, said that there was a bilateral contract – promise to make a will promise to come to CA and help them. – there was an offer and acceptance. e) Termination of Offer and Power of Acceptance: (1) Revocation – offeror can revoke the offer at any time before acceptance is made or consideration is given by telling the offeree that the offer is no longer open – need notification – unless it is an option contract. (a) Indirect Revocation – if offeree receives reliable information that the offeror no longer considers the offer open, then the offer is revoked. (b) Problem with revocation – people often need time to decide whether to enter into contracts. So offerors/offerees might bargain for time to consider the offer and give an Option Contract, promising not to revoke the offer within time. There must be consideration, and the parties must agree. This contract survives death and only come to an end by the terms of the contract. Dickinson v. Dodds (Ct. App – 1876): D agreed to sell his land to P and to leave the offer open until Friday 9 AM (option contract). P decided to accept the offer, but held off on telling D. P found out that D was selling to someone else (revoking the offer). Court says that this is an indirect revocation situation because P knew that the offer was being revoked. They say that there was no consideration for the option contract – not enforceable. Beall v. Beall (Ct. App. MD – 1980): 3 option contracts for land – the first two had consideration, but the third had no additional consideration. P contacts D to buy land (exercise the option) and she refuses to sell. Court sends back to trial court saying that even if there was no consideration, there may still be a valid offer since it was un-revoked, and whether there was acceptance – more facts are needed. (2) Death or Incapacity of Offeror – this is immediate termination. And the offer does not revive when offeror recovers from his incapacity. (3) Lapsing – offer lapses when it ends – this can come from the explicit terms of the offer, or after a reasonable time. (4) Rejection – rejection by the offeree dissolves the offer. Egger v. Nesbitt (Sup. Ct. Missouri – 1894): D has the deeds to the land, P has the tax titles. P sells his titles to Larkin. D asks for $400 to make a Q.C. Deed to P or Larkin. P replies to D asking him to send a blank Deed to his son and authorizes his son to put in the name. Court says that this acceptance rejected the previous offer and created a counter-offer since P added additional terms. ((Is this a deal the court will enforce?)) 1) Unenforceable Contracts a) Public Policy (e.g. illegal K): some contracts that courts will refuse to enforce i) i.e. contract to commit a crime, a tort, engage in sexual relationships, contracts dealing with families, etc. R.R. v. M.H. (Sup. Ct. Mass – 1998): Biological mother and contracting father entered into a surrogacy contract. Use the same policy notions underlying adoption – decide that the surrogacy contract is not enforceable b) Unconscionability i) Procedural Unconscionability: Imbalance in bargaining (1) Must show absence of meaningful choice (a) The party had no reasonable alternative to accepting it (b) They had no notice of it, OR (c) They were not able to understand it or appreciate its significance ii) Substantive Unconscionablility: “Shocking the conscious” (1) Must show that the terms are unreasonably favorable to one side – unfair to the party who did not have a meaningful choice iii) Remedy is non-enforcement if only part of whole K is unconscionable. Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture Co. (DC Cir. Apps. – 1965): Williams purchased many household items on an installment plan that she did not understand. When a party of little bargaining power, so no real choice, signs an unreasonable contract with little or no knowledge of its terms, its hardly likely that consent can be assumed to all its terms – case was remanded for further proceedings. c) Sufficient Definiteness d) Statute of Frauds: some contracts must be in writing and signed i) Common inclusions that are unenforceable if not in writing: (1) To guarantee someone’s debt (2) Sales of land (3) K to be performed more than one year from time of making (4) Sales of goods greater than $500 (UCC §2-201) (5) Wills e) Illusory K’s 2) Formation Defenses (things that happened at the time of formation)((contract is void or voidable)) a) Mistake ((Sherwood)) i) As to fact at time of contracting a fact that is important/material to the agreement ii) Mutual Mistake (1) §152: When mistake of both parties makes a contract voidable (a) Mistake of both parties (b) Made as to a basic assumption (c) Has a material effect on the exchange (d) Doesn’t bear the risk of the mistake iii) Unilateral Mistake (1) §153: When mistake of one party makes a contract voidable (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) Mistake of one party Made as to a basic assumption Has a material effect on the exchange Doesn’t bear the risk of the mistake AND, the enforcement would be unconscionable or the other party had reason to know of the mistake or his fault caused the mistake iv) It is harder to prove unilateral because it has more terms – probably because we want to protect the innocent person in this case, and do not think they should have to bear the risk. v) §154: When a party bears the risk of mistake (1) A party bears the risk of a mistake when (a) When the risk is allocated to him by agreement of the parties, or (b) He is aware at the time the contract is made that he only has limited knowledge, but treats this as sufficient ((assumption of the risk)), or (c) The risk is allocated to him by the court on the ground that it is reasonable in the circumstances to do so. Sherwood v. Walker (Sup. Ct. Mich. – 1887): P purchased a cow from D – had confirmation of sale in writing. D refused to deliver the cow because he discovered that the cow was not barren (as they had initially thought), was with calf, and was therefore worth more. Court says that the assent was made on a contract with a mistake in material fact – this mistake went to the root of the agreement – not the type of animal the sellers intended to sell, or buyers intended to buy. Donovan v. RRL Corp. (Sup. Ct. CA – 2001): D newspaper published a price wrong for a car, P attempted to buy the car. Unilateral mistake on the part of D’s newspaper ad. Uses RSC approach: Price difference is material, seller bore the risk of the mistakes (coz they messed up), but based on policy concerns, ask whether it is reasonable to allocate the risk to the seller – D satisfies grounds for rescission of the contract on the ground of unilateral mistake of fact. b) Misrepresentation/Fraud i) Fraud is a tort action for the harm caused when a duty to convey the truth is breached (1) Must show intent to deceive in tort ii) Misrepresentation (1) An assertion not in accord with facts (a) May be a “half-truth,” non-disclosure, silence, or concealment (2) A fraudulent or material assertion (a) Fraudulent: intent to deceive & person knows it is untrue (b) Material: would induce a reasonable person into K (i) Satisfied if seller has reason to know it is material for particular buyer (3) Show reliance in fact (actual reliance on statement) (4) Reliance must be justified (buyer reasonably thinks its true) (a) Opinions are tricky (i) Generally, not justified to rely on opinion (ii) If expertise of seller, facts behind opinion, or a special (family or fiduciary) relationship - then reliance could be justified Halpert v. Rosenthal (1970): P is the seller who said there were no termites. D discovers termites and refuses to close the deal. It was not fraudulent because P did not know about the termites, but this innocent misrepresentation still = misrepresentation since it has to do with a material fact. With two innocent party, the loss should be shifted to the more blameworthy (“simple justice”). Swinton v. Whitinsville Bank (1942): The contract was complete and 2 years later, P discovers termites. D is the seller who knew there were termites but concealed. Court says it is unrealistic/idealistic to expect D to disclose this – would disrupt transactions. Weintraub v. Krobatsch (1974): Rejects Swinton. There was a fumigation condition for the house, D the buyer discovered vermin and refused to close. Court says that the seller has an obligation in terms of justice and fair dealing to disclose the defect. c) Misunderstanding i) Parties have confusion about the thing they are contracting for mistake about the intent and the deal ii) §20: No manifestation of mutual assent to an exchange if the parties attach different meanings to their manifestations (1) Neither party knows/ has reason to know the meaning attached by the other (2) Or, each party knows/ has reason to know the meaning attached by the other. iii) §201: Whose meaning prevails? (1) Where they attach same meaning (2) Where they attach different meanings, its interpreted in accordance with the meaning attached by one of them if at the time the agreement was made (a) That party did not know of the other meaning, but the other knew the meaning attached by the first. (b) That party had no reason to know any different meaning Raffles v. Wichelhaus (England – 1864): Entered into a contract for the sale of cotton. But, buyer thought it was the Oct. ship “Peerless” while Seller thought it was the Dec. ship “Peerless”. Court said there was no contract because there was no mutual assent/ “meeting of the minds” to these specific terms (§20(1)(b)) d) Duress i) Voidable K – victim can choose to void ii) Physical threat §175 – destroys consent – recovery always allowed iii) Improper threat §176 (1) Regardless of the fairness of a bargain, if (a) Threat to commit a crime or a tort (b) Threat of criminal prosecution (c) Threat of civil action (sue) made in bad faith (d) Threat of breach of good faith and fail dealing in K (2) Unfair deal and (a) Threat that harms victim doesn’t significantly benefit person making threat (b) Effectiveness of the threat is increased by a history of unfair dealing (c) Threat to use power for illegitimate ends iv) Must leave no reasonable alternatives (resulting in unfair bargain) Totem v. Alyeska (1978): K between a contractor and a transporter to move construction materials by sea. Transporter made sufficient showing of economic duress since he was the victim of a wrongful or unlawful act or threat, and that act/threat deprived him of his unfettered will – enough to pass the sum. judgment stage and get to trial. Other test: 1. one party involuntarily accepted the terms of another, 2. circumstances permitted no other alternative, and 3. circumstances were a result of coercive acts of the other party. e) Undue Influence i) §177 - Unfair coercive persuasion by (1) Party who is dominant over the other party (one in position of power or confidence), or (2) Party who has a special relationship which would justify reliance on judgment (Relationship between parties) ii) The subject of persuasion is justified in expecting the other to look out for their welfare. iii) Hard because must establish that relationship exists, and unfair persuasion Odorizzi v. Bloomfield School District (1966): Teacher was arrested. While he was in severe mental and emotional strain, the superintendent and principal came and asked for his resignation. Dominant figures used excessive pressure to persuade a servient man. Overpersuaded him (factors listed on 302). – Undue influence 3) Excuses (things that happened after the formation) a) Impossibility/Impracticability (§261) i) §261: (1) Performance is impracticable ((must be something dramatic and outside normal course of events)) (2) Goes to a BASIC ASSUMPTION of the contract (3) No fault of party seeking relief – they have not assumed the risk Taylor v. Caldwell: A basic assumption of the contract was the existence of the Music Hall. If the Hall no longer exists, performance has become impossible. The Court implies a condition in by law. b) Frustration of Purpose i) The value of the performance dramatically changes ii) Same as impossibility, but the parties must be SUBSTANTIALLY frustrated iii) Classic case: Man rents room for Kings coronation, king gets sick so no coronation. Basic assumption of the coronation occurring has been frustrated. c) Conditions – i) For the most part, express conditions ii) Says that the obligation made in the contract is not effective unless some event occurs (§224) (1) Event (2) Not certain to occur (unless non-occurrence is excused) iii) Performance is not due UNLESS or UNTIL the condition occurs iv) The condition disappears when (1) parties agree on a time of expiration (2) in a reasonable amount of time, as applied by the court, or (3) circumstances have changed so that the condition could never occur now Peacock v. Modern Air: Subcontractors entered into a contract for a construction project. After they finished, D refused to pay because they had not received final payment from the owner. Within the terms of the K, there is a condition for full payment by owner – and the condition did not occur. The Court says that there was no condition as a matter of law – looking at intent, the clause was ambiguous and may just have been establishing a term and not a condition. d) Waiver i) Express waiver, or ii) Waiver implied by conduct (1) There was a condition on performance, but by conduct, the condition seems excused. – course of performance after the contract. Clark v. West: Express waiver: Parties entered into a publication employment contract. K said that if P abstained from alcohol while writing he would get $6/pg, but if he drank $2/pg. He drank. Court said that D expressly waived the condition by accepting the completed manuscript without objection and assuring P he would get the higher royalty rate. May v. Paris: Implied waiver: Parties entered into a 10 year lease with a guarantee on payment for the first two years. Guarantors agreed to extend their liability if the tenant was in default for the first two years. Tenant normally paid after the 15th of the month, but after the 2 years the landlord said that put him in default. Court says that the course of performance where the landlord accepted payment after the 15th has waived a right. e) Repudiation (One party repudiates before the breach – releases party from contract) i) Must be a clear manifestation of intent not to perform Hochster v. De La Tour: When there is clear manifestation not to perform before the breach occurs, the non-breaching party has a right to treat the K as over and move on/sue; or wait and see if breaching party retracts repudiation, and sue on the day the K was supposed to be performed. Court says that when the party anticipatorily repudiates the K, that will be considered the time of breach. Truman Flatt v. Schupf: K for property with condition that the buyer can void if not rezoned. Buyer sends letter withdrawing re-zoning; seller rejects; buyer still wants to buy; seller says K is void now because the new offer was a repudiation of K and terminated it; buyer sues. Court says that the letter was not a repudiation, just trying to get a lower price. And even if it was a repudiation, seller had no right to treat K as terminated coz buyer retracted before a material change in position was made. f) Material Breach (Substantial Performance is not a material breach) i) Essentially deprives other party of the benefit of their contract ii) Goes to essence of the bargain iii) §241: To determine whether breach was material, Court will look at: (1) Extent to which other party will be deprived (2) Extent to which the party may be compensated (3) Whether the breach will lead to forfeiture (4) Likelihood of party curing his failure (5) Extent of good faith and fair dealing of breaching party Gibson v. City of Cranston: K to become superintendent of school district. Term in K that said there would be evaluation procedures – this was breached, and she resigned. The breach was not material though so she was entitled to damages, but had an obligation to keep performing. She breached K when she resigned so the damages of the initial breach were offset. To be material, the breach must frustrate the entire purpose of the K and make continued performance pointless. Jacob & Youngs v. Kent: K to build home using a specific type of pipe in plumbing. P did not use the pipe, but D did not complain until the work was done. D refused to pay. If the breach was material, D would not have had to pay and would be released from performance. But, here P’s actions were not fraudulent, and the pipe used was not substantially different from the one requested – no material breach. ((What are the terms of the K?)) 1) Interpretation - What is it reasonable to conclude the parties agreed to/intended? a) If a K is ambiguous, courts may: (1) Interpret the contract to have enough content in it (strongest way) (2) Use implied terms – strengthen the case (i.e. “reasonable”, “good faith”) (3) Default Terms/Rules – “gap filler” – comes from a statute b) Modification/Pre-existing Duty: i) UCC §2-209: No additional consideration is necessary for modification to K’s ii) §73: When pre-existing duty is doubtful or the subject of honest dispute, modification is okay even without additional consideration iii) §89: Will enforce modification when its fair and equitable under unanticipated circumstances, to the extent provided by statute, or, to the extent that justice requires enforcement. iv) 2 settings for this: (1) Initial contracting setting (2) Amendments/Modifications to K’s (a) After the initial K is made, one party can force the other to do something because they are in a situation of necessity (b) Opportunism: sunk investments Alaska Packers Ass’n v. Domenico (1902): K for fisherman to sail from SF to AK during the fishing season. Once there, the fisherman demanded more $. Supervisor agreed to an altered K since they were so far away and there were no replacement workers. When they got back to SF, company denied the validity of the modification since there was not additional consideration. Court said that since they only did what they were already contractually obligated to do, no $. Angel v. Murray (1974): K between city and refuse collector. When the amount of refuse went up, collector demanded more $. P’s say the modification violated city charter and was made without consideration. Court said city voluntarily agreed to give more $ and amend, the modification was made when the K was not yet fully performed and the refuse had grown – additional $ was fair. c) Open Terms: parties sometimes agree to renewal terms, but weren’t ready at time of agreement to decide the price/rent. Basically says “we will fill this in later”. You can fill it in by: (1) Leave it to discretion of one party (2) Third Party discretion (3) “Formula” – CPI (determining inflation) (4) Agree to agree (especially when the reason for open terms is conflict avoidance, strategic, or bounded rationality) – looks like an illusory contract (doesn’t restrict discretion at all) Courts are often vary of enforcing these because there is no real contract. Varney v. Ditmars (Ct. App. NY – 1916): Sufficient Definiteness: P was employed with D. D told P that “I am going to give you $5 more /wk. And if you boys get me out of trouble, and get some [old] jobs started, on Jan. 1, I will close my books and give you a fair share of the profits”. P got sick and did not return from Nov to Dec. D fired him. Court says that the contract was unenforceable because they agreed to “fair share” but that is not sufficiently definite – dependent on intent and the subject matter Walker v. Keith (Ct. App. KY – 1964): Open Terms : Additional option in lease to extend for 10 more years dependant on a rent then agreed upon in accordance with “comparative business conditions”. Lessee gave proper notice to renew, but the parties did not agree upon a rent. Court says their role is not to create a new contract – if the parties don’t fix the terms with certainty, no agreement, no intent to be bound, and no legal obligations for the party. Renewal options still require certainty on terms. The option was illusory. Moolenaar v. Co-Build Companies, Inc. (US Dist. Ct. – 1973): P was a sheep/goat farmer who leased land. The lease was for 5 years/$375 month with a renegotiable renewal option for another 5 years. Land was sold to D. When P exercised the option, D said they would extend it to $17,000/month because of the high price they paid and the great value of the land if it was put to industrial use. Court said the renewal clause was valid and enforceable, it should be at a reasonable rate as calculated by the value of the land for agricultural purposes (according to original intent) and fair rent is $400 month. Fregaliment Importing Co. v. B.N.S. Int’l (S.D.NY – 1960): Ambiguous Express Terms: Dispute over whether the right thing had been delivered and whether money was owed when both sides think they contracted for something different. Dictionary, USDA definitions, then a) Trade Usage – legal test: (1) Whether the party is “in the trade” – or have actual knowledge, and are held to understand the trade usages (2) Party must show (i) That it is well-established (ii) Notorious (use experts to establish this) b) Purpose – “Commercially Reasonable” – what they were trying to establish with the contract (1) Relevant to look at price (broiler birds more expensive – so D would have incurred a loss by intending to sell those) (2) Look at the purpose of usage for the buyer c) Course of Performance d) Negotiations – they clearly said they wanted the English word to apply – they SHOULD HAVE KNOWN. e) Looked at context, etc. Court said that in the end the express terms (written in the contract) dominate – when there is a contract written down, it dominates all the other oral or implied “contracts” d) Parol Evidence – comes up only when there is a written document that someone is saying is an agreement i) Based on the premise that agreements may be made along the way of making a contract– but if they produce a piece of paper on the way (with signatures) ((a written document)), if that document is intended by the parties to be a final and complete agreement or an integrated agreement, then the court will ignore the negotiations or modifications, and only pay attention to the “entire agreement” in the written documents (a) Cannot even allege that there were prior or other negotiations – even if they were said, if there is a written final complete document, that is all that matters and all the court will look at. (b) “4 corners rule” – do not go beyond the 4 corners of the paper 1. Problem of Ambiguity 2. Problem of not integrated ii) 2 settings/versions (1) Interpretation of written document/”contract” (a) Bars extrinsic evidence ((contemporaneous or prior oral/conduct/activity)) to prove meaning of term unless term is ambiguous (reasonably susceptible of multiple meanings) (b) Court must first establish that there is something ambiguous to apply this – then establish that the meaning that you want applies. (i) Using extrinsic evidence both times (what Kazinsky is upset about) – use to prove ambiguity and then to prove your meaning is right. (2) Proof of prior oral agreement/extrinsic agreement (a) Parol evidence rule bars proof if: 1. K is fully integrated (final and complete) – cannot conflict and cannot supplement, OR 2. K is partially (some terms) integrated – cannot conflict, but can supplement with consistent terms (ii) Use extrinsic evidence to determine integration and again once decided. Nelson v. Elway (Sup. Ct. CO – 1995): P is trying to establish that D owed him $50/car to prove that this has been breached in order to collect damages. Parol Evidence applies because they must determine whether there was an oral service agreement that should/should not be included. Court says the document is fully integrated, so no additional extrinsic evidence. Esbensen v. Usermore (Ct. App. CA – 1992): P is trying to establish that good cause was required for termination. Parol Evidence applies on whether the agreement was fully or partially integrated – court says it is partially integrated, and good cause does not conflict with the written document, so P should be allowed to attempt to prove (probably not enough proof for the breach of agreement because of the 2 week notice clause) Trident Center v. Connecticut (Ct. of App. 9th – 1988): P is trying to establish that D is obligated to accept prepayment of the loan at a 10% fee. Parol Evidence is whether the prepayment clause is ambiguous – Court says under CA law, they are entitled to admit evidence to prove if there is ambiguousness. e) Gaps in contracts i) Sometimes the contracts do not tell the court what the obligation should be ii) What can the court do to determine the obligation? (1) Interpretation of the document with no gap (a) If it does not say anything about something, just assume that it was not meant to be there (b) Some terms might be IMPLIED-IN-LAW (as opposed to IMPLIED-INFACT *true intent*) (i) Implied-in-law terms can come from statutes (UCC) (From partnership law) 1. Default rules a. Can contract out of it b. If you choose not to contract it though, the law will default c. (most of the UCC are default rules) 2. Mandatory rules a. Not allowed to contract out of them (ii) From common law – good faith and fair dealing obligation 1. Implied in every contract 2. In order to fill gaps, a court will supply reasonable term Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon (Ct. App. NY – 1917): Court faces a gap because there is a promise from Wood that he has a duty to try to market designs or to place certificates of endorsement – there is nothing in the contract that says how much effort Wood has to make, if any – under the contract if he did not have to do anything, she did not get anything. If promise for him to sell something was not implied there would be no consideration, and it would be illusory. Court fills in the gap saying that “reasonable efforts” must be implied. IMPLIED IN FACT since it is what they intended. Locke v. Warner Bros., Inc. (Ct. App. CA – 1997): Court faces a gap because P is looking for an obligation on their part that they consider her on merit (she has reason to believe that they only accepted her scripts to help Eastwood. Court implies term IN LAW for an obligation of good faith and fair dealings – definitely an exercise of discretion, but it must be made in good faith at least (cannot be a sham deal). Hobin v. Coldwell Banker (Sup. Ct. NH – 2000): P says that D is under an obligation not to allow other franchisees in the area, but there is an express term that says that they are under no such obligation, and can add other franchisees (non-exclusive). Court says that they can only imply a good faith reasoning if the contract would otherwise be illusory – but there was real consideration in this agreement. ((Remedies)) 1) Expectation Damages is what P is entitled to (basic remedy for breach of contract) ((sets standard and limits reliance damages)) a) Must be shown with adequate certainty (not speculative) b) Put P in position as if contract performed c) Duty to mitigate d) §347: (1) Loss in value of performance + (2) Incidental or consequential losses caused by breach – (3) Loss/cost avoided by not having to perform b) “Incidental” damages: costs incurred in responding to the breach c) “Consequential” damages: lost profits on other opportunities that would have materialized if there had been no breach. (in contrast with lost opportunities) i) Hadley v. Baxendale (1854): the consequential had to have been reasonably foreseeable. Hawkin v. McGee (1929): K for a 100% perfect hand. Breach: ruined hand. Damages: at trial, P was awarded damages for pain and suffering + (value of the hand pre-surgery – value of hand post-surgery). Court says that these damages are incorrect – it should be: value of a promised 100% hand – value of hand post-surgery. 2) Reliance Damages (as alternative) a) Put P in position as if no contract b) Loss must be caused by reliance on the contract c) Limited by expectation interest d) §349: (1) Out of pocket expenditures + (2) “Lost opportunities” – (3) Loss suffered if performed if proved by D Hollywood Fantasy v. Gabor (1998): K for $11,000 for an appearance at an event. Breach: no show at the appearance. Damages: Claimed to have lost $250,000 in future vacation packages and $1 million on a TV series, but the expectation damages were just speculative. They can recover reliance damages as an alternative - $57,000 spent on printing, marketing, etc. in reliance of her appearing. Fair v. Red Lion Inn (1997): K for at will employment. She was on leave for injury and learned she was pregnant. She was wrongfully fired, and later the employer offered to reinstate her but she rejected the offer. Her reasons for rejecting the offer were not special circumstances that showed a reasonable basis for rejection – she did not mitigate or minimize her damages appropriately. So her damages will be limited. 3) Punitive Damages a) Only if on independent tort (mostly awarded in business cases) b) “Efficient Breach”: when it might be better from an economic point of view to breach than to perform – the gain is greater than the loss. i) Total value of the breach for “everyone” > value of performance Paton v. Mid-Continent Systems: K for franchise that has an exclusive territory provision on it. Breach: D set up a franchise in the area. P is requesting punitive damages. Indiana law allows punitive damages for breach of K with elements of fraud, malice, negligence, or oppression – no evidence that any of these elements were there in D’s actions. It was an efficient breach – and does not justify punitive damages. 4) Liquidated Damages a) Must be reasonable efforts to eliminate the actual damages b) Liquidated Damages provisions (agreed damages as remedies) will be enforced by the courts if: (1) Actual damages contemplated at the time of contracting are uncertain, or difficult to determine, and (2) The amount is not grossly excessive compared to the actual damages O’Brian v. Langley School: K for school enrollment had a liquidated damages clause that said any withdrawals must be made by a certain date or they would have to pay a full year’s tuition. O’Brians withdrew late and refused to pay. Court said the O’Brians were entitled to have the opportunity to prove that the clause was unenforceable, discovery should be allowed. 5) Restitution Damages a) Return any benefits that P gave to D ((recover benefits given to breaching party)) (ie. deposits) b) Where someone is seeking the remedy of rescission – to void the contract i) See under formation defenses: (1) Fraud (2) Misrepresentation (3) Misunderstanding (4) Undue influence (5) Duress 6) Specific Performance a) When there is no adequate remedy at law in money damages b) SP is of special interest to the buyer, and not easily obtainable Triple-A Baseball Club v. Northeastern Baseball: K to sell/buy a AAA baseball franchise. Term in the K that if the Eastern Clubs refuse to approve the sale, modifications would apply. Breach: AAA refuses to sell. Court grants SP since they cannot get the AAA team elsewhere and they cannot calculate the profits lost (and NBI had a special interest in the team and profits won’t compensate). ESPN v. Baseball: K for 6 broadcasts of a baseball game. Breach: they were not broadcast. Baseball is not able to provide any certainty to the damages lost or any formula for the calculation of damages. Court decides they are entitled to nominal damages. Need sufficient certainty for damages – cannot just be speculation.