A Deleted Scene from The Myth of the Rational Voter by Bryan Caplan

advertisement

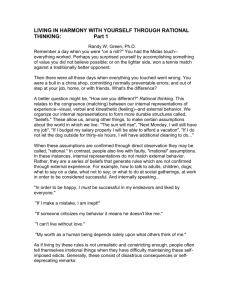

A Deleted Scene from The Myth of the Rational Voter by Bryan Caplan Am I Irrational? So far I have neglected the question likely to loom largest in the minds of philosophically inclined readers. Anyone who says that "Human beings are irrational" opens himself up to the deduction "Since you're a human being yourself, on your own theory you're irrational too." It is easy to dispose of this simplest version of the objection: When I say "Human beings are irrational" I mean that "Most human beings are irrational some of the time," not "All human beings are always irrational." But the careful reader can construct a better version of the self-referential objection, something along the lines of: Caplan says that people tend to be irrational on questions where there are no direct material costs of being wrong. But there are no direct material costs to Caplan of being wrong on most if not all of the questions he addresses in this book. Even if he is utterly mistaken, he will continue to receive his salary for the rest of his tenured existence. Admittedly, this is only a "tendency," but considering the fact that Caplan has gone to the trouble of writing a book on this topic, he probably has a big emotional investment in his answer. I take this possibility seriously. In all honesty, my situation is precisely the kind in which I claim that people's attachment to rationality is weakest. In many instances, admittedly, I could take refuge in the fact that my views are widely shared by other economists, and that neither self-serving bias nor ideological bias can empirically account for our shared distinctive outlook. But whenever I claim to make a novel contribution, I cannot hide behind a professional consensus which ipso facto does not yet exist. What then? I could offer numerous "cheap-talk" reassurances. I could tell you that what really motivates me is the desire to be right, not just to feel right. I might also point out several instances where I changed my mind in spite of the fact that my initial belief was emotionally comforting and materially cheap. My first academic publication explained why the Austrian economists who introduced me to the economics discipline have little to add that is both original and true. My closest friends will vouch that I prefer the company of insightful critics to admiring followers. But I doubt that any of this would or should convince a rational outside observer. "That's what they all say!" is too strong – the Pope does not surround himself with free-thinkers. Nevertheless, few beliefs are as emotionally satisfying as "Unlike other people, who believe what makes them feel best, I believe whatever is most likely to be true." Rather than making a mostly futile effort to convince you of my own cognitive virtues, I prefer to direct your attention inwards. Do your best to put your feelings and ideological commitments aside, and judge my claims on their own merits. If you then determine that I am in large part correct, there is little need to speculate about my psychology. If on the other hand you deem that I have little of value to offer, you are not going to change your mind even if I somehow convince you of my undying love of truth. One curious possibility is that critics will adopt my basic framework and then use it to label me and my favorite empirical examples "irrational." Rational irrationality is a natural framework for anyone who questions the status quo in a democracy. That includes not just professors of economics or toxicology, but also globalization protestors, radical protectionists, theocrats, and communists. If Vladimir Lenin were alive today, perhaps he would seize rational irrationality as the one useful insight of bourgeois economics: The public irrationally underestimates the benefits of Leninist policies because its members are individually powerless to impose them. In fact, all of these "crazies" have a point. When dealing with abstract, "impractical" areas like politics and economics, it is unfair to infer that a viewpoint is wrong just because it is unpopular. The best way to evaluate contrarian arguments, once again, is to put your feelings and ideological commitments aside and actually listen. Then the alleged crazies can be judged on their merits. A final interesting possibility is that I am basically right but fail to temper my judgments with due modesty. There is a wry passage from Adam Smith that undeniable makes me uneasy: Some general, and even systematical, idea of the perfection of policy and law, may no doubt be necessary for directing the views of the statesman. But to insist upon establishing, and upon establishing all at once, and in spite of all opposition, every thing which that idea may seem to require, must often be the highest degree of arrogance. It is to erect his own judgment into the supreme standard of right and wrong. It is to fancy himself the only wise and worthy man in the commonwealth, and that his fellow-citizens should accommodate themselves to him and not he to them.i Nevertheless, pleas for greater modesty should be viewed with suspicion on both strategic and intrinsic grounds. Strategically, the problem with modesty is that we live in a culture of energetic self-promotion. In this environment, humility is the equivalent of unilateral disarmament. When everyone is fighting for attention, modesty is a recipe for being entirely ignored. More fundamentally, though, neither I nor any other economist I know claims to be infallible or anything close. All I claim is that on average, economists' judgments about economic policy are a lot more trustworthy than the public's. It is good for experts to be aware of their limitations. But it is equally important to keep those limitations in perspective, to remember that limited expertise is better than none at all. i T of MS, p.?, Part 6 Sec 3 Chap 2