File

advertisement

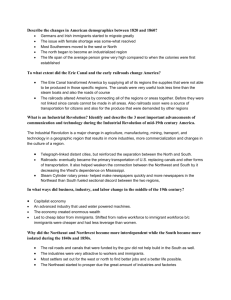

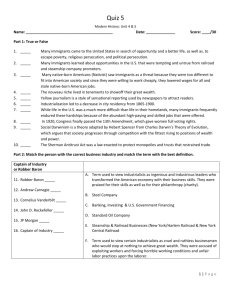

Kevin Moffatt 12/11/13 E Guiding Questions: Early Industrialization pages 261-272 1. How did the United States change from the War of 1812 to the Civil War? The US changed in many was between the War of 1812 and the Civil War. In 1812, America was essentially an agrarian nation, based on small towns, what few decent sized cities were there was sometimes a flourishing mercantile economy. In addition, there was a growing manufacturing activity, concentrated in the Northeast, however, the majority of Americans were farmers and trades people, working within an economy that was still mainly local. By the time the Civil War began in 1861, the US had transformed itself, and although most Americans were still rural people, most American farmers were now part of a national, and increasingly international, market economy. More importantly, the US had developed a major manufacturing sector and was beginning to challenge the industrial nations of Europe for supremacy. At this time the nation had experienced the first stage of its industrial revolution, and wile the changes that were produced were far from complete, most Americans understood that the world had changed for good. 2. What were the new economic characteristics by the middle of the 19c of the Northeast? The western lands? In the South and Southeast? The new economic characteristics in the middle of the 19c in the Northeast was that it had become an economic ally of the Northwest, and both were rapidly developing a complex, modern economy and society, increasingly dominated by large cities, important manufacturing, and commercial farming. It was an unequal society, but a fluid one, committed to the idea of free labor. Relatively few white Americans lived west of the Mississippi River, but parts of these western lands were becoming art of large-scale commercial agriculture and other enterprises and were creating links to the capitalist economy of the Northeast. These changes also occurred in the South and Southwest. Southern agriculture, especially cotton farming, flourished better than ever in response to the growing demand from textile mills in New England and elsewhere, but while the southern states were becoming increasingly a part of the national and international capitalist world, they also remained much less economically developed than their normal counterparts. As the North was becoming more committed to the fluidity and mobility of its free-labor system, the South was becoming more and more resolute in its defense of slavery, and ultimately these economic differences would result in the Civil War. 3. What were the three trends that characterized the American population between 1820 and 1840? What were some of the reasons for the rapid population increases in this time period? The three trends that characterized the American population between 1820 and 1840 were that: one, the population was increasing rapidly; two, much of the population was migrating westward; and three, much of it was moving towards towns and cities. One reason for the substantial population growth was improvements in public health. The number and lethality of epidemics (such as the great cholera plague of 1832) slowly declined, and the nation’s overall mortality rate followed this trend. Another reason was an increase in birth rate. IN 1840, white women bore an average of 6.14 children each, a decline from the very high rates of the eighteenth century, but still substantial enough to produce rapid population increases, particularly since a larger proportion of children could expect to grow to adulthood than had been the case a generation or two earlier. 4. Why was the rise of New York City so phenomenal? What forces combined to make it America's leading city? The rise of New York City was so phenomenal because by 1810 it was the largest city in the US. This quick growth was amazing because of the rapid increase in population, when from 1840 to 1860 it raised form 312,000 to 805,000 (it would have been 1.2 million but at the time Brooklyn was considered a separate municipality). This huge growth was amazing in the 19th century, making New York one of the most populated cities in the world. This growth was partly a result of its superior harbor. It was also a result of the Erie Canal (completed in 1825), which gave the city unrivaled access to the interior. Liberal state laws that made the city attractive for both foreign and domestic commerce also contributed to New York’s growth. 5. How were the Irish and German patterns of settlement in America different? What were the reasons for this difference? The Irish and German settlement in America were different, because while the great majority of the Irish settled in the eastern cities, where they swelled on the ranks of unskilled labor, most Germans moved on to the Northwest, where they became farmers or went into business in western towns. One reason for this difference was wealth: while German immigrants generally arrived with some money, the Irish often arrived with practically none (think of Angela’s Ashes). Another important factor was gender, for while most German immigrants were members of family groups or were single men (for whom movement to the agricultural frontier was both possible and attractive), many of the Irish immigrants were young, single women, for whom the movement west would be much less plausible. These women were more likely to stay in the eastern cities, where factory and domestic work was available. 6. Why did industrialists, land speculators, and political bosses welcome large numbers of immigrants? Industrialist, land speculators, and political bosses would welcome large numbers of immigrants because they had new employees, or buyers, or political followers. The influx of immigrants helped industrialists because it provided a larger base for unskilled, cheap labor, which was a necessity for the success of industrialism. Land speculators loved it because they had many more potential buyers to sell land to, and a bigger market usually drives prices up because someone will be willing to pay more money. Political bosses welcomed the immigrants because they were potential followers for a cause, whom could be used for political means. 7. List all of the arguments that the nativists made against the influx of large numbers of foreign immigrants. The nativists argued many things, some including basic racism, some claiming that the new immigrants were inherently inferior to older-stock Americans (ironically forgetting that they were originally immigrants). Others viewed the new immigrants with the same contempt and prejudice with which they viewed African Americans. Many nativists avoided racist arguments but argued nevertheless that the newcomers were socially unfit to live alongside people of older sock, and that the immigrants did not hold sufficient standards of civilization, claiming for evidence the urban and rural slums they lived in (some nativists assumed that these slums were a choice of the immigrants wretchedness, instead of their extreme poverty). Others, mostly workers, complained that because foreigners were willing to work for low wages, they were stealing jobs from the native labor force. Religion was also a matter; Protestants, observing the success of Irish Catholics in establishing footholds in urban politics, warned that the Church of Rome was gaining a foothold in the American government. Whig politicians were angered because many of the new immigrants voted Democratic, so they were naturally against immigrants that hurt the success of their party. Others complained that ht immigrants corrupted politics by selling their votes. Many olderstock Americans of both parties feared that immigrants would bring new, radical ideas into national life, which would mess up the political balance of the US at the time. 8. How did the nativists respond politically to the surge in immigration between 1830 and the 1850s? The nativists responded politically to the surge in immigration between 1830 and the 1850s by creating a number of new secrete societies to combat what nativists had come to call the “alien menace”. Most of these societies originated in the Northeast, but some later spread to the West, and even to the South. The first of these societies was the Native American Association, which began agitating against immigration in 1837. In 1845, nativists held a convention in Philadelphia and formed the Native American Party (unaware that the term used to describe themselves would one day become a common label for American Indians). Anti-immigration sentiment peaked in the 1850s, when many of the nativist groups combined in 1850 to form the Supreme Order of the Star-Spangled Banner. This new, bigger order endorsed a list of demands that included banning Catholics or foreign-born people form holding public office. They also endorsed more restrictive naturalization laws, and literacy tests for voting. They adopted a strict code of secrecy, which included the secret password, used in lodges across the country: “I know nothing”. Ultimately, members of the movement became known as the “Know Nothings”. Gradually, these Know-Nothings turned their attention to party politics, and after the election of 1852 they created a new political organization called the American Party. In the East, the new organization scored an immediate success in the 1854 elections, in which they cast a large vote in Pennsylvania and New York and won control of the state government in Massachusetts. In other places, their progress was more modest. Western members found it hard to not oppose naturalized Protestants, and after 1854, the strength of the Know-Nothings declined. Their most lasting impact was its contribution to the collapse of the existing party system, which was organized around the Whig and the Democratic parties, and the creation of new national political alignments. 9. Why did Americans continue to use, whenever possible, water routes for transportation and travel? What advantages did water have over land? Americans continued to use water routes over land routes because they were far superior to land roads traveled by mostly horse drawn vehicles. Water routes could be traveled much quicker, and were adequate for the growing nation’s needs. Larger rivers were especially quicker, such as the Mississippi and the Ohio, where traffic, mostly flat barges little more than rafts, floated quickly downstream, transporting goods and people down the larger distance quickly. The only downside was that vessels that raveled upstream were agonizingly slow, and sometimes took up to four moths to travel the length of the Mississippi. The rivers became vastly more important by the 1820s, as steamboats grew in number and improved in design. These new riverboats carried the corn and wheat of northwestern farmers and the cotton and tobacco of southwestern planters to New Orleans in a fraction of the time of old barges. Then, from New Orleans, oceangoing vessels took the cargoes on to eastern ports. In addition, steamboats also developed significant passenger traffic, and companies built increasingly lavish vessels to compete for this lucrative trade (although most passengers couldn’t’ afford the luxurious amenities and often slept in either in the hold or on the deck). 10. How did Americans propose to overcome the geographic limitations on water travel? What role was the federal government forced to play in this? Why? Although an improvement of highways across the mountains provided a partial solution, the better proposal of the canal system. The canals had a much larger economic interest, however, the federal government did not take a large step into this transportation system, because at the time, it was the belief of the federal government that in state transportation improvements should be left to the states, not the federal government. As a result, the federal government did not take a role in the development, and as canal building was too expensive for private enterprise, the building was left to the states. 11. Which area took the lead in canal development? What was the effect of these canals on that section of the country? How did other sections respond to this example? The ambitions state governments of the northwest took the lead in constructing them, and New York was the first to act. It had the natural advantage of a good land route between the Hudson River and Lake Erie through the only real break in the Appalachian chain, but the engineering tasks were still imposing. The distance was more than 350 miles, which was several times as long as any of the currently existing canals in America at the time. High ridges and a wilderness of woods interrupted the route. After a long debate over the practicality, the canal advocates prevailed, and digging began on July 4, 1817. The building of the Erie Canal was the greatest construction project America had yet undertaken. Although the canal itself was simple (a forty foot wide and four foot deep ditch with towpaths along the banks for horses or mules that were to draw the boats), hundreds of difficult cuts and fills, some o them enormous, were required to enable the canal to pass through hills and over valleys. Stone aqueducts were necessary to carry it across streams, and eighty-eight locks, of heavy masonry and great wooden gates, were needed to permit ascents and descents. However, once finished, it was not just an engineering triumph, but also an immediate financial success. Traffic was soon so heavy that within about seven years tolls had repaid the entire cost of construction. By providing a route to the Great Lakes, the canal gave New York direct access to Chicago and the growing markets of the West. The canal system extended farther when Ohio and Indiana provided water connections between Lake Erie and the Ohio River. These canals helped to create them all the way to New York; the beginnings of an intricate network of canals in America. Next, rival cities along the Atlantic seaboard attempted to catch up. Boston did not even try to connect itself to the West, and Philadelphia and Baltimore had the formidable Allegheny Mountains to contend with. Maryland’s canals never made it passed the mountains, and in the South, Richmond and Charleston aspired to build water routes to the Ohio Valley, but they were never completed. 12. What advantages did railroads have over other forms of transportation? What were the results of the introduction of major trunk lines on the nation into different regions of the country? The advantages that railroads had were that they could carry passengers and freight, and could be built in a wider variety of places compared to canals. However, the railroad system was not improved greatly until the 1830s and 1840s. Railroads and canals were soon competing bitterly, but railroads had so many advantages that when they were able to compete freely with other forms of transportation they always prevailed. New railroad networks spread throughout the country in the 1850s, tripling the amount of trackage in just ten years. An important change in the railroad development was the trend toward the consolidation of short lines into longer lines (known as “trunk lines”), and by 1853, four major railroad trunk lines had crossed the Appalachian barrier to connect the Northeast with the Northwest. These trunk lines connected all the different parts of the nation, especially the east with the west. By weakening the dependence of the West on the Mississippi, the railroads helped to weaken further the connection between the Northwest and the South. 13. What role did state and local governments play in the development of rail transportation? the role of the federal government? Capital to finance the railroad came from many sources. Private investors provided part of the funding, and railroad companies borrowed large sums from abroad, but local governments, states, counties, cities, and towns, often contributed capital because they were so eager to have railroads serve them. This support came in the form of loans, stock subscriptions, subsidies, and donations of land for right-of-way. The railroads obtained substantial additional assistance form the federal government in the form of public land grants. For example, in 1850, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and other railroad advocate politicians persuaded Congress to grant federal lands to aid the Illinois Central, which was building form Chicago toward the Gulf of Mexico. Other states and their railroad promoters demanded the same privileges and by 1860, Congress had allotted over 30 million acres to eleven states in order to assist the railroad construction. 14. How did innovations in communications and journalism draw communities together? How did these innovations help divide the sections? The innovations in communications and journalism brought communities together because they formed communities together into a common communications system. In 1846, for example, Richard Hoe invented the steam cylinder rotary press, making it possibly to print newspapers rapidly and cheaply. The development of the telegraph, together with the introduction of the rotary press, made it possible for much speedier collection and distribution of news than ever before. By 1846, newspaper publishers from around the nation formed the Associated Press to promote cooperative news gathering by wire, for no longer did they have to depend on the cumbersome exchange of news-papers for out-of-town reports. This quickly delivered news helped to bring communities together by giving them something to talk about, creating close, talkative, and even sometimes gossipy communities. On the contrary, the rise of the new journalism helped to feed sectional discord. Most of the major magazines and newspapers were in the North, reinforcing the South’s sense of subjugation. Southern newspapers tented to have smaller budgets, and reported largely local news. Above all, the news revolution, along with the revolutions in transportation and communications that accompanied it, contributed to a growing awareness within each section of how the other sections lived and of the deep differences that had grown between the North and the South that would eventually cause a war.