Case Studies in Use of DNA Evidence

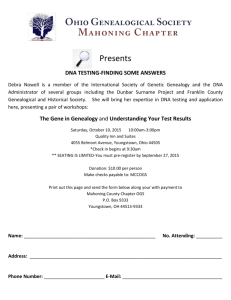

advertisement