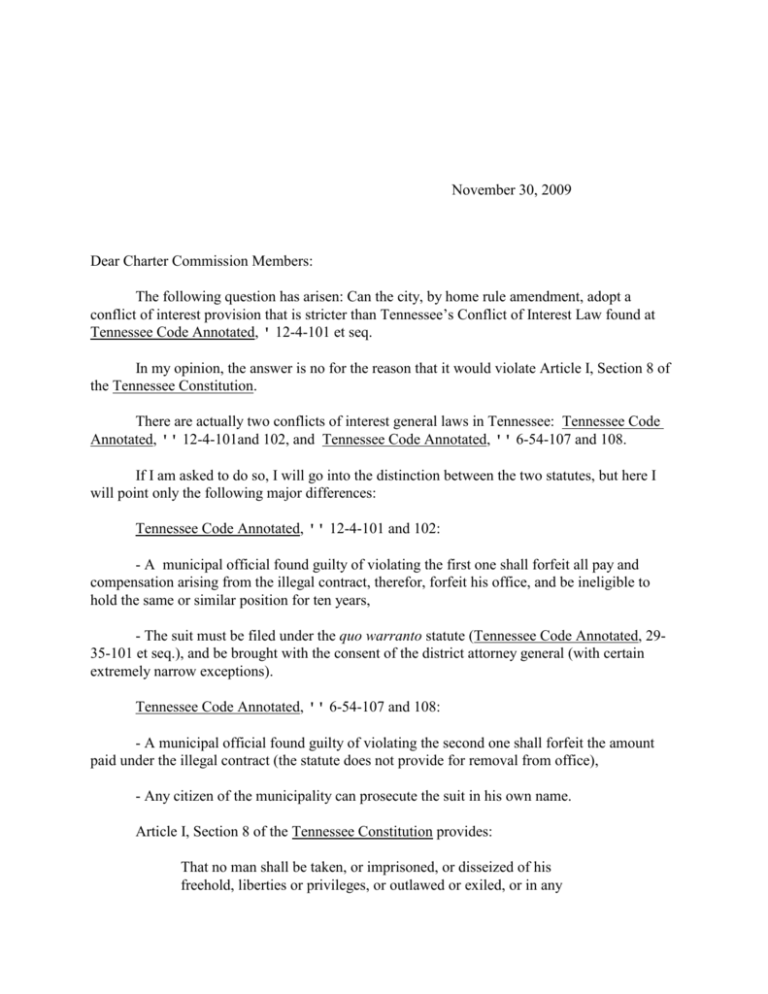

Conflict of Interest Provision public

advertisement

November 30, 2009 Dear Charter Commission Members: The following question has arisen: Can the city, by home rule amendment, adopt a conflict of interest provision that is stricter than Tennessee’s Conflict of Interest Law found at Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 12-4-101 et seq. In my opinion, the answer is no for the reason that it would violate Article I, Section 8 of the Tennessee Constitution. There are actually two conflicts of interest general laws in Tennessee: Tennessee Code Annotated, '' 12-4-101and 102, and Tennessee Code Annotated, '' 6-54-107 and 108. If I am asked to do so, I will go into the distinction between the two statutes, but here I will point only the following major differences: Tennessee Code Annotated, '' 12-4-101 and 102: - A municipal official found guilty of violating the first one shall forfeit all pay and compensation arising from the illegal contract, therefor, forfeit his office, and be ineligible to hold the same or similar position for ten years, - The suit must be filed under the quo warranto statute (Tennessee Code Annotated, 2935-101 et seq.), and be brought with the consent of the district attorney general (with certain extremely narrow exceptions). Tennessee Code Annotated, '' 6-54-107 and 108: - A municipal official found guilty of violating the second one shall forfeit the amount paid under the illegal contract (the statute does not provide for removal from office), - Any citizen of the municipality can prosecute the suit in his own name. Article I, Section 8 of the Tennessee Constitution provides: That no man shall be taken, or imprisoned, or disseized of his freehold, liberties or privileges, or outlawed or exiled, or in any manner destroyed or deprived of his life, liberty or property, but by the judgment of his peers or the laws of the land. In State v. Hamby, 63 S.W.2d 515 (1933), the question of whether a 1933 private act applying only to Hamilton County by population bracket violated Article 1, Section 8. The private act provided that it would be a misdemeanor, punishable by fine and imprisonment for any member of the County Court or any person related within the third degree to any member of the County Court or any person related within the third degree to any member of the county court to enter into any contract for the sale of property, rendering of any service, furnishings of any supplies, or doing other things for a consideration to be paid out of public funds of the County or any public funds of the State disbursed by any officer or agent of the County and over which the County Court may have jurisdiction. [At 515] The Tennessee Supreme Court held that the private act violated Article I, Section 8 of the Tennessee Constitution, for several reasons: - First, The term “law of the land” meant the general law. - Second, “Both the words ’liberty’ and ’property’ in the foregoing section include the right to make contracts.” - Third, “It is true,” said the court that: The right to contract is subject to curtailment, limitation, and destruction, by the Legislature when done pursuant to “the law of the land.” [Citation omitted by me.] .... The general rule is that the Legislature cannot pass special acts, but there are certain exceptions to this rule. [Citation omitted by me.] Classification from a population basis is permissible where the classification is based upon reason, is natural, and is not arbitrary and capricious. [At 516] - Fourth, even though some cases support private acts because they are based upon reason, are natural and not arbitrary or capricious, said the court: We are unable to perceive any justification for denying to the large number of citizens of Hamilton county affected by this act their constitutional right to contract when citizens similarly situated in other counties of the state are not deprived of that privilege. Conceding, as did the chancellor, that political nepotism is a “hateful thing,” we are unable to say that it is more prevalent in Hamilton county than in the other counties of the state, and if such a law would improve political conditions in Hamilton county, such a law wold likewise benefit the other counties of this state.... [At 516] The plaintiff argued that Hamilton County was distinguished from other counties of the state in a way that would support the private act by virtue of the fact that what is now Tenacious Code Annotated, '' 12-4-1201 and 102 had been repealed as to Hamilton County in 1911. The Court acknowledged that: The question as to the validity of the attempted repeal of the general law for the benefit of Hamilton County is not before us for determination. But see Woodard v Brien, 82 Tenn. (14 Lea) 523. [At 516] Although the “validity of the attempted repeal of the general law for the benefit of Hamilton County [was] not before us for determination,” the court’s advice or admonition to “But see Woodard,” on that issue plainly telegraphed what it felt about the “attempted repeal.” Woodard, is a 1884 case that held that a 1877 general law that applied only to Davidson and Shelby counties by population brackets violated Article XI, Section 8 of the Tennessee Constitution, the court explaining that: By Article XI, section 8 of the Constitution, it is provided that the Legislature shall have no power to suspend any law for the benefit of any particular individual, nor to pass any law for the benefit of any particular individual, nor to pass any law for the benefit of individuals consistent with the general laws of the land, nor to pay any law granting to any individual or individuals, rights, privileges, immunities or exemptions other than such as may be, by law extended to any member of the community who may be able to bring himself within the provisions of such law.... The court reasoned that: The act in question is so clearly a suspension of the general law for the benefit of the two counties mentioned as to require no argument to establish the proposition. “The Legislature may suspend the operation of the general laws of the state; but when it does so the suspension must be general, and cannot be made for individual cases or for particular localities....” [At 520] Again, as the Hamby court itself indicated, the question of whether the Legislature could have repealed what is now Tennessee Code Annotated, '' 12-4-101 and 102 as to Hamilton County was not before the court. For that reason, its reference to Woodard is not binding on the court in this day. But the Tennessee Supreme Court in Hamby, by referring to Woodard, clearly telegraphed that it would not abide the suspension of Tennessee’s Conflicts of Interest Law for a local government, if it were faced with that question. But a home rule charter containing conflicts of interest law stricter than the two Tennessee Conflicts of Interest Laws, would run into problems under Article I, Section 8 of the Tennessee Constitution. Although Hamby applied to a private act, it is clear that home rule cities are subject to the Tennessee Constitution the same as are other cities, and that under Article I, Section 8, the right to contract cannot be limited except by general law. A provision in the city’s home rule charter that is more restrictive of the right of citizens to contract than is Tennessee’s Conflicts of Interest Law found at Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 12-4-101 and 102, or of Tennessee Code Annotated, '' 6-54-107 and 108 would not meet the requirement that the restriction be accomplished by general law, and we need not even reach the question of whether it would be a general law that is reasonable, natural and is not arbitrary and capricious. However, with respect to the latter, I can think of no reason why the City could be distinguished from the rest of the local governments of the state in the area of conflicts of interest. Presumably, the City could ask the Legislature to exempt it from the application of Tennessee’s two conflicts of interest laws, so that it could enact its own charter provision governing conflicts of interest, but even if such an attempt succeeded, it could face a challenge that the “suspension” of the general law as to it would violate Article XI, Section 8 of the Tennessee Constitution. State v. Hamby’s reference to Woodard (and subsequent cases on the suspension of general law) would support that challenge. Sincerely, Sidney D. Hemsley Senior Law Consultant SDH/