KNOWLEDGE CULTURES AND HIGHER EDUCATION

advertisement

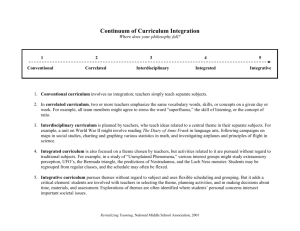

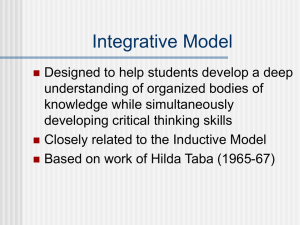

KNOWLEDGE CULTURES AND HIGHER EDUCATION: ACHIEVING BALANCE IN THE THE CONTEXT OF GLOBALISATION ELWYN THOMAS INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION,UNIVERSITY OF LONDON INTRODUCTION The nature of knowledge has been a changing phenomenon for centuries and institutions of higher education have, in the main, attempted to adapt by changing their curricula, access procedures and organisation, to meet the challenges which knowledge change has brought about. Many individuals nowadays, have to handle many frames of reference in order to understand themselves, and the world around them. This has been described by Barnett (2000), as an age of “supercomplexity”, the outcomes of which will be changing perceptions of the function of knowledge and profound challenges to the future of higher education. Globalisation and internationalism are now central issues world wide, affecting all areas of higher education Altbach (2002a), in which increased knowledge production and distribution, the consequences of globalisation, open up new opportunities for the future of higher education, Gibbons (1998). The speed and complexity of change over the last decade, has certainly made an examination of the rationale for higher education even more acute. In many, but not in all ways, the source of the problem stems from the institutions of higher educations themselves, which have been responsible for the generation and production of many forms of knowledge. From an international perspective, the changing nature of knowledge in higher education has raised challenges stemming from the emergence of 1 new domains of knowledge and the need to rethink the task of knowledge integration For instance, Weiler (1996) has indicated how new domains of aesthetic, normative and spiritual knowledges have recently emerged, alongside the rise of so called indigenous knowledges, and the effect such developments will have, and are having, on the ways we need to look at the future of the curriculum and pedagogy in higher education. Hayhoe (1996) has signified that a more integrated and systematic way of thinking about universities and knowledge is needed, and that by bridging both comparative education theory and international relations theory, a more successful integration could be achieved. leading presumably to qualitative changes in higher education that are needed for the 21st century This paper will confine itself to a discussion of the challenges faced by faculties of education and other related social sciences, with reference to the profound changes in the nature of knowledge cultures, especially in the context of internationalism and globalisation. While the overall focus of the discussion that follows relates to university education, references will also be made to college education, because teacher education which is one of the principal thrusts of the paper, is still in many countries of the world, carried out are in colleges which are outside the university sector and under government control. The author’s recent experience of working in higher education in East and South East Asia will be reflected in what follows. The main argument put forward here will embrace three key notions these are, knowledge cultures, globalisation and internationalism The author defines the three notions as follows. Firstly, a knowledge culture is understood here to mean on going encounters between a group of individuals that share common discourse and interests, the outcomes of 2 which may be transient or durable knowledge. Secondly, globalisation is essentially multifaceted and intimately related to free trade, technological innovation and information communication, demographic change linked to the development of global societies, socio-cultural, economic and ideological convergence. Globalization is primarily an exogenous process, which means that ideas and information arising from outside a system, have the potential to produce fundamental change to that system But there is an endogenous aspect to the consequences of globalisation, in which certain forces within a system have the potential to counter exogenous influences, by adapting and enriching them further. Much of the endogenous nature of globalisation is closely related to the culture of a society, Thomas (2003). Finally, internationalism is viewed as the development of knowledge communities which transcend national boundaries, but in which national interests are able to persist. It is essentially a process of knowledge transfer and exchange which embraces administration, teaching, research and professional development. The argument which runs through this paper is; that one of the principal tasks facing the future of higher education, especially in the emergent economies of the world, is to achieve an acceptable, integrated yet dynamic balance between new knowledge cultures, and existing cultural knowledges, (including local or indigenous), so that cultural identities and societal continuity can be maintained and enriched, the catalyst for the enrichment being globalisation and internationalism. The paper will encompass three themes, the first of these will examine the changing nature of knowledge cultures and how far higher education should reflect uniformity and diversity. The second theme will tackle the challenge of achieving an Integrative Education, which attempts to 3 balance new knowledge cultures with more traditional knowledge cultures including local and indigenous forms of knowledge. The third theme will examine the relationship between integration and balance in the context of Integrative Education, and the role research and professional development should play in the process. THE CHANGING NATURE OF KNOWLEDGE CULTURES (i) Knowledge cultures and curriculum change - general trends In the past five years, the debate about conceptualising curriculum change, Barnett(2004), Barnett, Parry, Coate (2001), Burn (2002), Bourner(2004), Northedge (2003)has intensified within higher education, and has been a response to a number of factors not least,the increasing impact of the age of supercomplexity in which we all now live. Central to the debate has been the nature of knowledge and how knowledge generation, production and distribution have changed, and the extent to which such changes have initiated a complete re-examination of the curriculum of higher education, especially in the developed economies. If we consider that the nature of knowledge arises as a shared discourse within a textual community Bruner(1996), and that such discourses can be underpinned by encounters which contribute to a body of knowledge and understanding which can be transient or durable, we can therefore perceive knowledge as comprising many knowledge cultures and subcultures. A knowledge culture that has existed for centuries at universities has been labelled “traditional”, and nowadays referred to as the basis of a Mode 1 curriculum, in which content was pre-eminent and the student generally 4 was a passive recipient in the teaching -learning process. With the influence of modernisation and more recently globalisation, another knowledge culture has emerged in which application and the practical value of content is considered to be as important as the content itself. This is known as “emerging” and forms Mode 2 curriculum , and embraces a knowledge culture which emphasises active participation on part of both student and university tutor. Barnett (2001) refers to this as part of an “emerging curriculum” which in essence is an emphasis on “knowing how”, and is as important as “knowing what”. These trends have lead to what is known as the commodification of higher education, where knowledge is mainly perceived as a commodity to be bought by the consumer. From a traditional knowledge base, a repertoire of skills and techniques have been developed further, for the benefit of multinational corporations, the world of financial institutions and the market economy. In response to the trend towards commodification, universities and other academic institutions have developed new roles as providers of commercial and business expertise, so making commodification their central raison d’etre. Many governments have actively supported such developments either directly eg Singapore, Malaysia or indirectly eg United Kingdom. Of particular concern to this paper, is the emergence of an important challenge to the epistemological tradition of university education relating to the place of traditional disciplines,( embraced within the sciences and humanities), in a world that is rapidly becoming more internationalised and influenced by globalisation. Weiler (1996) has discussed at length the need for higher education to embrace new domains of knowledge such as aesthetics, normative and spiritual studies 5 etc, to widen both the appeal and relevance of higher education in a changing world. New knowledge cultures such as the politics of knowledge, gender and a serious study of democracy ,( discussed by Weiler) are already being included in the curricula of many western academic institutions. The theory and practice of Information Technology, Networking, and the development of advanced digital technology and their theoretical underpinning, are other examples of new knowledge cultures that are included as part of most higher education curricula in developed countries. The new information knowledge cultures mentioned above however, are not isolated knowledge cultures as they pervade much of science, technology, medicine and engineering disciplines. It’s the author’s hope that not only should these new knowledge domains continue to figure in higher education curricula, but that future proven knowledge domains, will also be part of what is offered in higher education. The inclusion of the new with the old knowledge cultures marks an exciting future for higher education, a future that will affect higher education internationally It is to some of the international perspectives that we turn. (ii)Knowledge cultures - international perspectives To date, the debate about the changing the nature of knowledge and the relationship to the reconceptualisation of the curriculum in terms of Mode 2,has been focussed mainly in developed countries. But at the international level, questions about the commodification of knowledge and education have also arisen, albeit less prominently in developing countries. Altbach( 2002) points out that education is not only a 6 commodity to be bought and sold, but an essential process which underpins civil society and national participation. Neave (2002) is also concerned about the extent to which the commodification of knowledge endangers academic freedom and therefore minimises the autonomy of university education in society. Altbach in particular, has stressed that developments in higher education in the West towards increasing commodification , have filtered through to higher education institutions in developing countries. This means a growing western influence on university teaching and learning has taken place, that could be construed as neo-colonialism and a new form of cultural imperialism. The growth of transnational higher education in the form of twining partnerships and other forms of close academic exchange, has further added to western styled commodification being filtered into university education in the emergent economies eg South East Asia, although to a lesser extent in East Asia. This has not only challenged the ownership and transmission of knowledge on the part of less developed economies but has lead to cultural ,social and epistemological traditions being eroded, downgraded or at worse neglected altogether. The impact of transnational education it seems have had mixed blessings as far as higher education is concerned. The curricula in many universities in the emergent economies needed to be modernised, and this has in varying degrees been successful. For instance, in countries such as Nigeria, Tight (2003) and China, Easton(1991) the emphasis across most faculties has been to maintain the “knowledge based” Mode 1 curriculum, emphasising the value of specialised knowledge. However, there is less emphasis on Mode 2 approaches to teaching and learning but with little evidence of integration 7 across disciplines. For instance, from a cultural standpoint the state universities in Malaysia have ensured that the curriculum for undergraduate students have access ( sometimes mandatory), to religious(Islamic) and other cultural features of Malaysian society. Nevertheless, the private institutions of higher education in that country appear to have gone down the commodification road, with little apparent commitment to interesting students in the socio- cultural aspects of life in Malaysia. (iii) Whose universal values? Many academics from the West share the view that their traditions of seeking out knowledge and the methods they employ, have values that have developed over the centuries, and are now so universal that they transcend all cultures. Often cited as a basis of this universalism, have been the adoption of democratic principles of ancient Greece, the JudaicChristian tradition of values, and starting in the late 17th Century, the beginnings of modern scientific methods of inquiry and knowledge. This position is now challenged by an increasing number of academics in other parts of the world, especially China Easton (1991), India and other Asian countries. However, the effects of both internationalism and especially globalisation, appear to reinforce the primacy of Western knowledge, and the way it is being applied to higher education, through the advent of a Mode 2 type approach to teaching and learning in many non - Western countries. The continued dominance of Western technology in the context of Borderless Higher Education, Pincas (2002), new approaches to Distance Learning and Networking between institutions and professionals through the internet, has meant that the universality of Western knowledge, and 8 approaches to teaching and learning remains a key issue, when such developments need to be attuned to local cultural concerns about curricular relevance. The process of integration could be a valuable mechanism here, so that a balance be achieved between the various cultures of knowledge necessary for a university curriculum to prepare students the world of work. Integration could also assist in meeting the need to successfully attune both universal and relativistic values and traditions for a particular cultural context. It is to the process of integration and its role in reconceptualising the university curriculum that we now turn. INTEGRATING KNOWLEDGE CULTURES Integration in higher education is not new, it has been a feature for many decades of policy formulation affecting organisation, administration and not least the curriculum. However, the need and intensity for more integration relating to the explosion of knowledge in the latter part of the 20th century, has meant that integration has taken centre stage. It is therefore desirable at this juncture in the paper to raise four questions concerning integration. Firstly, we need to ask why is integration necessary in the first place ? Secondly, what is being integrated, thirdly, to what extent should a university education for the 21st century, replace General Education for an Integrative Education? Finally, how could integration achieve a cultural balance? (i) Why integrate? The effect of internationalism and globalisation has fuelled knowledge production in the last few decades to such an extent, that more and more academics have begun to analyse their knowledge areas closely, and 9 discovered considerable areas of over lap. The amount of overlap has been recognised as a reason for rationalising content and procedures in both research and teaching across the knowledge spectrum. The advent of ICT has not only contributed to the knowledge explosion today, it pervades almost all knowledge areas taught in higher education . It is a key tool for academics and researchers to communicate their ideas and propagate research findings. ICT will also generate new knowledges. Therefore, the main rationale for integration is to rationalise knowledge cultures, identifying common principles and concepts that can be valuable for knowledge transfer across disciplines and which will act as a sound basis for knowledge application. Integration would also make the organisation of knowledge more manageable. (ii)What is being integrated? The term integration means combining parts into a whole. At present, higher education curricular are undergoing considerable changes as efforts are being made to integrate various disciplines and approaches to form new knowledge cultures. So integration is already a current issue in re-conceptualising the curriculum. The main argument of this paper rests on achieving balance between different knowledge cultures, therefore the notion of integration is key to the whole idea of attaining balance. It might be useful at this point in the paper to briefly examine the integration issue within higher education, and to ascertain what aspects of the curriculum are affected. Integration in one form refers to combining parts of a subject discipline into a more coherent whole, for instance biotechnology is an amalgam of parts of biological, physical sciences, technology and mathematics. Pertinent to the present discussion on higher education integration, is the extent to which ICT and Networking 10 Systems can be integrated into other knowledge areas such as science, technology and language studies. This integration may be coined epistemological, however epistemological integration is not a new phenomenon, and certainly not confined to the sciences, as recent developments in combining parts of philosophy, psychology and sociology in the wider study of education has shown. Another type of integration involves integrating Mode 1 and Mode 2 more effectively for the purposes of making content more meaningful and useful. This trend is happening already in many developed economies, as a response to market requirements and the demand by multinationals and industry for relevant skills training .This type of integration can be termed supra-curricular. Supra-curricular integration, takes a take a bird’s eye view of teaching and learning in higher education, and operates at course planning level. Recently, Barnett ( 2004) has coined the term Mode 3 which refers to “knowing in and with uncertainty” and is a knowledge culture that is about uncertainty, relevant to the age of supercomplexity. It is a mode which attempts to come to terms with an ever complex world, where the conditions for human existence have become more unpredictable than ever. In this context, a supra- level curricuar integration would combine all three modes, the dominance of each mode depending on context and what influences pervade at a particular time. Another example of supra-curricular integration would relate to the current discussions on the value of General Education in the University curriculum . Burn (2002) discusses in her editorial on “General Education to Integrated studies”, (a special issue on the subject in the journal Higher Education Policy), the need for professionals in higher 11 education to adapt to the forces of globalisation and internationalisation. One stage in this adaptation process would be to re-examine the role and status of General Education. Burns points out that a new form ( author’s Italics), of general education needs to be developed so that it is more integrative and international. As a result, students will be better equipped to meet the challenges of the age of supercomplexity. The new form of General Education would it is hoped, make students and staff more aware of global and international issues, and encourage sound critical thinking and creativity. The need to provide an integrative approach is therefore crucial. In view of the importance of having a sound and effective General Education which addresses both generic and specific demands in the era of supercomplexity, it would be useful if we examine what form a new type of General Education might take .A discussion of the issue would also be valuable in pursuing the main argument put forward earlier in this paper, with its emphasis on achieving balance through an integrative approach. (iii) General Education into Integrative Education? The concept of a “General Education” goes back well before the scientific revolution which started in the 17th century. General education embraced the notion of an education for the mind ,through a study of philosophy, mathematics and rhetoric amongst other knowledge cultures In many ways, this early form of General Education was “integrative” in the sense that the main focus of study at a University was the improvement of the mind and to develop more rounded and “integrative human beings” Scott (2002). The scope of General Education increased by the end of the 19th century, resulting in fragmentation of knowledge 12 into many disciplines which marked the start of a steady departure from scholarly eclecticism. This fragmentation intensified during the 20th century and seemingly continues into the present millennium. Knowledge fragmentation is a natural consequence of scientific and technological discoveries, as well as the development of diversified knowledge in the humanities and social sciences. However, the increase in knowledge and subcultures of knowledge has been spurred on further by the advent of ICT, making access to knowledge wider, and greater in terms of capacity. Furthermore, ICT has its own specific knowledge culture and subcultures which has added to the fragmentation of knowledge. It is quite obvious in the light of the explosion of knowledge, and the ease to which it can be accessed , that the curriculum of higher education needs to adapt to these challenges both now and in the future. In view of such developments, we need to ask at least two key question about the nature, value and place of a General Education in the 21st Century. Firstly, is there a need for a General Education as part of higher education, if so, what form should it take? Secondly, should any notion of a wider education be abandoned in the face of more commodification, which encourages specialisation and further fragmentation ? The view of the author is that a balanced form of education should be offered to students in higher education, in which aspects of a General Education needs to be integrated as a response to the inevitable consequences of a further knowledge explosion. However, the search for more generic attributes would be necessary, to make curricular priorities more 13 manageable in the light of a predictable knowledge expansion and curriculum planning. The task of integration will not be an easy one. As commodification is likely to continue, there are those who would be unwilling to concede much space in a curriculum, to what is considered traditional and out of date. On the other hand, there are those who seek to preserve aspects of higher education as an opportunity for the education of the “whole person”. The fact is that both positions are understandable and tenable, so compromises will need to be made. Whoever wins the argument, a new form of General Education needs to emerge. General Education may not be the best term to use nowadays, in view of its past association with esotericism and charges of elitism unfounded or otherwise? Furthermore, recent trends in the production of new knowledge cultures discussed above would also signal a change of terminology. Integrative Education may be a more appropriate title in a world that is being transformed by the existence of knowledge networks, and is characterised by uncertainty and rapid communication. Under these conditions, an integrative framework is essential to meld new knowledge cultures with some of the more traditional ones, and provide a basis for job flexibility, as well ensuring that students will also receive an education that will enhance personal development, Barrie &Prosser (2004). Scott (2002) has suggested the term “integrative learning” instead of General Education, but this minimises the role pedagogy and therefore that of the university tutor. It can also be argued that “learning” is only part of the educative process and so “education” would be a more all embracing term to use as a substitute. 14 From an international perspective, the World Bank-UNESCO Task force on Higher Education and Society (2000), dedicated a section of their report to discussing the importance of General Education for the future of higher education in developing countries. Their conclusions about General Education were positive, stressing its role in preparing students for “flexible knowledge careers” for the world of work, and also developing a broad range of social attributes which could enhance their understanding of “global integration” However, the task force also emphasised that General Education should not be seen by developing countries, as a Western product, but should develop a General Education reflecting their own cultures, needs, and values. It is to the development of integrative education in the context of the achieving cultural balance that we now turn. (iv) Integrative education and cultural balance If an undergraduate curriculum in an emerging economy adopts an Integrative Education model, it is essential that alongside the need to include selected aspects of Mode 1 and Mode 2 knowledge cultures, the cultural contexts which reflect a particular society are also included, and integrated into the curriculum. For instance, the issue of language is particularly sensitive especially where a former colonial language( ie English or French) is retained as the language of instruction, local languages will also need to be included, either as second languages or in some case as “co- instructional” languages as in Singapore and recently Malaysia. This ensures a vital linguistic balance in the education of students. In countries like India and Malaysia, instruction may use two languages 15 during undergraduate studies for different disciplines. For instance, while the humanities curriculum is taught in the mother tongue, science and technology are often taught in English or a mix of both. Another aspect of attaining cultural balance in the context of an Integrative Education, would concern cultural/spiritual values. In Thailand, Buddhism would have a key place in the university curriculum for all students irrespective of their main studies. Similarly in Malaysia, Malay undergraduate students are expected to include Islamic studies as part of their university education. The subjects of language and cultural /spiritual values are just some examples of where a cultural balance needs to be achieved, in any plan that will use an Integrative Education model as a basis for a higher education curriculum. There are other cultural areas that would also need to be considered such as the inclusion of indigenous languages and customs, cultural history, indigenous philosophies and secular value systems. However, if an integrative model is to be used, the main objective should be to ensure cultural balance, so that the education a student receives not only prepares him or her for the age of supercomplexity, but the student’s cultural heritage is not neglected in the process. KNOWLEDGE CULTURES AND THE NOTION OF INTEGRATIVE EDUCATION The discussion so far has been framed within the general debate about re-conceptualising higher education curriculum per se. The basic assumption which underlies much of the discussion that follows, is that 16 the notion of an Integrative Education would hopefully provide a framework for what, and how knowledge is taught in higher education. For an Integrative Education to be successful, it has to address the needs of society by providing knowledge which is relevant, effective and a preparation for the world of work.. It also needs to provide opportunities to enrich a student’s personal development, which would be of benefit to the wider society. The challenge for an Integrative Education, in whatever form it manifests itself, would be to reflect the needs and expectations of a society in a balanced, integrated and acceptable manner. In the first part of this section key factors which influence the development of a particular model of Integrative Education will be discussed. The discussion will then continue to examine these influences, with reference to higher education in the emergent economies of South East and East Asia. Particular emphasis will be placed on the issues of cultural diversity and cultural inclusivity, in the light of the effects of globalisation and internationalism on the form a model of Integrative Education might take. The main thrust of the discussion will be limited to examining Integrative Education in the context of Education and Teacher Training. (i) Integrative Education and influencing factors Those responsible for developing an Integrative Education as a basis for an undergraduate curriculum in the age of globalisation and internationalism, will need to take account of at least six key influences which are shown in Figure 1 below These are (a) New Global Knowledge Cultures, (b) Internationalism, (c) National/political, (d) Regional (e) Traditional/historical (f) Socio –Cultural. It would be helpful to provide a brief description of each of the six influences. 17 FIGURE 1 (a) New Global knowledge cultures Such knowledge cultures would include both the theory and impact of ICT(Information Communication Technology), the need for more flexibility and application of information in changing work environments, a readiness to deal with uncertainty and rapid change in an age of supercomplexity. Looking to the future, it would also be necessary to anticipate the advent of new knowledge frameworks, which are likely to arise in an increasingly globalised world. This could be realised by encouraging teaching and learning to emphasise innovative and creative thinking. Global cultural influences would also require future undergraduates to be more adaptive, and to consolidate new ideas with greater rapidity; globalisation often being a rapid process. Therefore, knowledge is important in the way it is selected, processed, understood, critically analysed and presented. (b) Internationalism The influence of internationalism would entail the effects of increased networking between institutions of higher education, and between higher education, industry, marketing/financial institutions, commercial / multinational organisations and international bodies such as the UN and Development agencies eg World Bank. In many parts of the developing world especially in South East Asia, internationalism has had a very special influence through organised patterns of university exchange and interchange. The twinning of universities, technological institutions and 18 certain specialist higher education colleges in Malaysia, Thailand, Taiwan and Singapore with counterparts in Australia, United Kingdom and USA, have now become part of the landscape of higher education in the fields of Business studies, English, commerce, law, applied science and medicine. The initial purpose of such partnerships was to make up the short fall in university places in countries where the number of state universities were small. To date, twinning is still and will remain a feature for some time to come. At another level, internationalism also flourishes, with students going from their home country to study in overseas countries. This has been a trend that goes back before World War Two (WW2),continuing apace after independence was granted in its wake. Both types of international interchange have resulted in a marked flow of Western ideas and traditions from North to South. Therefore, the future development of Integrative Education will be influenced to some extent, by past experiences arising from such international interchange, that seems set to continue. However, the flow is not all one way Teichler (2004), as countries like Taiwan, Japan and Singapore have highly developed industrial and technological expertise, particularly in ICT. These developments are already being reflected in the higher education systems of these countries. Therefore some of the countries of East and South East Asia are already becoming donors as well as receivers with benefits for both.. 19 (c ) National/ political In most countries, higher education is too important to be left in the hands of private bodies, even if they play an increasingly important role in providing places for students in many countries. As most higher education will therefore be the responsibility of national governments, they would naturally have a key role to play in what is included in an Integrative Education curriculum. In instances where new knowledge cultures and their application, might appear to challenge the political status quo, as well as social and religious sensitivities, socio- political and national interests would, through government policy, ensure that such challenges are met. (d) Regional influences Regional influences on education vary from one part of the world to another. For example, in the European Union, in view of “on going programmes” of rationalisation between member states, both Mode 1 and Mode 2 knowledge cultures are showing signs of having a greater commonality in terms of purpose, content and approach within higher education. Accreditation and entry requirements are also starting to be rationalised across member states, which would also have implications for assessing student performance in an Integrative Education Curriculum in a particular country of the union. As yet, Asian countries that belong to ASEAN and the Pacific Rim, regional influences in higher education are not as strong as they are in the EU. However, in Japan, Korea, and increasingly China, there is growing evidence of academic and technological exchanges between 20 these countries of the North, and the emergent economies of southern Asia. Nevertheless, regional influences are not as intense as they are in Europe, but with greater economic and political cooperation between countries within East and South East Asia, the regional factor is likely to become more significant (e) Traditional /Historical A key influence that stems from traditional/historic factors, includes the status of traditional disciplines that have been part of university curricula for many years. For instance, subjects such as philosophy, pure and applied sciences, well established humanities like history, language and literature are amongst the well known subjects being taught. Their influence is still strong and remain crucial knowledge cultures. It is clear from an examination of university curricula in countries like Singapore and Malaysia, the links forged with British higher education before independence continue, inasmuch that traditional disciplines are still flourishing and becoming even more specialised. Although, it is not claimed here that older knowledge cultures are flourishing for any neo-colonialist reasons. Their retention is seen as a necessary as part of higher education provision. It is true however, that new subjects such as ICT, business studies, economics and management are also favoured areas and much in demand by students. But it remains to be seen whether an Integrative Education if adopted in these countries, would continue to retain the place of traditional knowledge cultures and what status and role they would have? 21 (f) Socio-cultural One of the affects of both globalisation and internationalism on higher education, would be the extent to which new knowledge cultures could supplant not only the traditional disciplines mentioned in (e), but devalue and erode cultural knowledge and traditions what are an integral part of a society. There is a growing recognition of the importance of indigenous knowledges Heckt (1999) Semali (2002) Thomas (2002), as part of a curriculum at both school and university levels. Knowledge domains that reflect cultural values, secular and religious, would need to be included as part of the mosaic of an Integrative Education for many countries. It is important that higher education should be an experience for students, which not only provides them with knowledge and skills for job opportunities in society, but that they experience an appreciation of their cultural heritage whether it be through the study of language, religion, art or cultural history. (ii) Educating Teachers through an Integrative Education In order to focus the discussion more succinctly, let us examine how an Integrative Education could be developed for the study of Education, and particularly Teacher Education, which in many countries increasingly takes place at a university or higher education institute. The growing trend worldwide points to making teaching an “all graduate” profession in the foreseeable future. Therefore, the issue of providing an Integrative Education for the education and training of teachers, is highly relevant in meeting the challenges faced by teachers in the new age of supercomplexity. 22 An appropriate teacher education curriculum in the age of supercomplexity is perhaps best viewed from recognising changing needs of learners, teachers and the workplace. It is possible to distinguish between two forms of need, namely extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic needs feature in all modern societies where a highly skilled and qualified work force is required. Meeting these needs usually targets the short to medium span of a person’s working life. Extrinsic needs are closely associated with the functioning of society and are part of a person’s motivational regimen. Intrinsic needs have an inner longer term personal dimension, which is integral to person’s development as a human being eg moral and spiritual development, love of learning and aesthetics. Figure 2 below shows three knowledge components that trainees would study in order to meet extrinsic, and intrinsic needs. Component A includes knowledge cultures that meet extrinsic needs of the workplace, and society in general. Component B includes knowledge cultures that are meant to widen students’ exposure to world issues, internationalism as well as their own cultural values. The knowledges included under B are meant to meet intrinsic needs This component also provides opportunities for students to study their own cultural heritage and to critically analyse it when and where desirable. Component C (ICT) has a dual function firstly, it is a knowledge culture in its own right act, with a theoretical framework and a growing amount of specialist knowledge. Secondly, ICT acts a bridge between components A and B, as it provides a means of communication between for all three components. Component C therefore fulfils both extrinsic and intrinsic needs. 23 FIGURE 2 HERE All three components would embrace Mode 1 and Mode 2 in each of the knowledge cultures listed. If we were to include Barnett’s Mode 3 in this scheme of Integrative Education, likely places could be Education Theory and Practice, Pedagogy or possibly one of the Education Disciplines (iii) Balancing cultural contexts within an integrative curriculum Cultural diversity is an important issue in the provision of education, so much so, that societies have had to face the fact, that educational provision needs to be diversified to meet the challenge of multicultural education which embodies much of cultural diversity. According to Corson (1998), post modernity has two distinct but conflicting features, on one hand a trend away from centralisation, mass production and consumerism which embrace schools, universities and state health services, and on the other hand, a development of flexible technologies and an emphasis on accountability, diversity of educational provision and more autonomy for higher education . This means, that while cultural diversity has begun to be addressed as an issue in curriculum planning in many societies, the need to equip students to survive in the ever competitive market place, has understandably become the priority, and the special cultural needs of students are in danger of being ignored. Therefore, any society that recognises the need to address the issue of cultural diversity as part of a policy of education for diversity, must seek a consensus between the conflicting demands of postmodernism outlined above. 24 Achieving this consensus means that education needs to be diversified, reflecting a culture sensitivity for both teachers and learners, as well as preparing students for the age of supercomplexity. A key determinant in attaining the success of any consensus, depends on the way teachers and lecturers will be trained, and the extent to which teacher educators are sufficiently prepared for the task. This raises the need for a different form of teaching and teacher education, reflecting cultural diversity and thence cultural sensitivity. An Integrative Education model as depicted in Figure 2, if appropriately integrated, would go some way to meeting the growing need to balance the role and status of new knowledge cultures with the existing ones, which include the values and traditions of a society. However, integration must be the responsibility of a particular society, in order that a balance is achieved which is relevant and acceptable to that society. Clearly, a move towards a more integrative form of higher education within and across different faculties, will mean that new roles and responsibilities will emerge for academic staff, which in turn will need new forms of training. Figure 3 attempts to spell out these requirements in the case of teacher and teacher educator training. Similar sets of roles responsibilities and training could also be mapped out for other higher education disciplines eg medicine, community and social work. Whatever model of Integrated Education is developed for different faculties at a university, the six influences discussed above, will have an important impact on how students from a particular society will be educated in the future. So the issue of well thought out integrative strategies for an Integrative Education will be the key to its success. In the remaining section of this paper we will examine further, the integrative process and what role research should play in making it an effective instrument for achieving 25 balance in higher education curricular. FIGURE 3 HERE ACHIEVING BALANCE THROUGH INTEGRATION: FACING REALITIES While much of this paper refers to knowledge cultures in higher education in emerging economies, the issues of balance and integration of knowledge are also ones that advanced economies face in their task to meet the challenges of globalisation and internationalism. Furthermore, while education and particularly teacher education, have been a focal exemplar in our discussions on how higher education curricular can be reconceptualised for the 21st century, changes affecting other disciplines would face similar problems. Therefore, the discussion that follows in the final section of the paper will have some relevance for curriculum change in higher education world wide. However, the main argument which underlies this paper, specifically pin points achieving balance in higher education between newer knowledge cultures and existing ones, so that emerging economies will be able to adapt to the ever increasing influences of globalisation and internationalism. The gist of this argument will be the main thrust of what follows In attempting to achieve some form of balance in the preparation of a higher education curriculum for the age of supercomplexity, policy makers, planners, academics and those with vested interests in higher education need to be aware of the realities. Apart from the magnitude and complexity of the task itself, four sets of realities emerge, these are identified and discussed below 26 (i) Socio- Political Realities It would be churlish not to recognise that political realities play a part in most aspects of higher education, and nowhere more evident would political decisions be felt, than in countries that have a rich cultural heritage embracing language, values, customs, religious beliefs although not necessarily with long established democratic institutions. In a country like Thailand a common language and religion is shared by over 95% of the population and therefore, the issue of cultural balance and integration will be to a great extent coloured by these realities. So any changes to the curriculum which ignore these realities would certainly be viewed with suspicion and maybe hostility. Circumstances in Korea and Japan are somewhat similar to those of Thailand, as both these countries have a mother tongue spoken by almost 98% of the population and a religious belief system shared by a majority in their respective populations. The Malaysian situation is different. Malaysia is a pluralistic society where different languages are spoken alongside the official Bahasa Malaysia, and different religions are freely practised by various sections of the population. Although the majority Malay population are Muslims. Any decisions about cultural balance therefore , will affect all cultural groups and clearly most key decisions about curricular change will be political. Although there are differences, the situation in Singapore is not dissimilar from that of Malaysia as curricular decisions affecting cultural, linguistic and religious matters need to be treated with respect and sensitivity for all four ethnic groups. In many countries of South East Asia, political realities may also include 27 the politics itself. For instance, perceptions about new knowledge cultures having the potential for developing insensitivity to certain political policies as well as religious and cultural values, may be construed as a threat to the status quo. Therefore ,any attempts to achieve cultural balance in higher education as far as the curriculum is concerned would need to address the nature of this reality with some thought. (ii)Economic The growth of international banking, marketing, commerce, multinational organisations and Hi- Tech industries are some of the main consequences of globalisation. This growth has in turn, lead to the need for more graduates with expertise in marketing, global economics, management, ICT, applied sciences and training across traditional knowledge and new knowledge cultures. Much of the impetus, is the result of market forces which translated into the economics of a society acts as a powerful factor, when decisions have to be made about curricular balance, and the nature of further integration concerning all knowledge cultures. The impact of the knowledge economy has meant a restructuring of industry and the jobs market around ICT Neave (2002), underlining the power of ICT as a new knowledge culture. In countries that practise social engineering as a means of realising success in the goals for national development, the effects of globalisation invariably means more pressure being put on higher education to produce graduates with the expertise demanded by market forces. In other words, achieving curricular balance will need to face the very real challenge of commodification ,and this in turn arises from globalisation and a society’s response to it. (iii) Epistemological realities 28 The notion of balance in the context of a higher education curriculum begs two questions the firstly, why is a balance required in the first place? Secondly, what is being balanced? The answer to the first question is contextual in two senses. Firstly, the explosion of knowledge has meant that it is no longer possible for university graduates to know all aspects of their chosen field of study. In other words, the global context in which higher education has to operate, needs to offer students a balanced curriculum, in order that essential knowledge and skills are provided. Secondly, there is a more limiting context to the why question, and this refers to a particular society. Achieving balance in this sense, means ensuring that knowledge and training required for students to enter the world of work, does not dominate and replace the need and opportunities for students to explore their own cultural heritage, including cultural and religious values, language, traditions as well as new knowledge domains outlined by Weiler and cited earlier in this paper. It is argued here, that integration is a mechanism that would assist the task of achieving curricular balance, and it has been suggested in the previous section ( see Figures 2 and 3) how balance could be attained in the case of Teacher Education. Of the many realities faced by those attempting curricular balance, are factors such establishing priorities, decisions about allotted time and space, and the nature of integration itself. Figures 2 and 3 refer to listed knowledge areas where integration is a looser arrangement. Deeper and closer integration between subjects eg Biophysics, International Studies, Citizenship etc would also be part of achieving balance, but in these cases within knowledge areas. Both looser and deeper forms of knowledge integration assist balance, but decisions about what, how and how far to integrate, present challenging realities in attaining the goal of an effective and relevant curriculum. 29 (iv) Supra-epistemological realities Earlier in this paper, a discussion of supra-curricular integration mentioned that this form of integration would a take a bird’s eye view of teaching and learning in higher education, and operates ultimately at the course planning level. Furthermore, it was pointed out that supra- level curricular integration could combine all three curricular modes, the balance between each mode depending on context and what influences pervade at a particular time. The issue of context appears yet again in our discussion about the realities facing the task of achieving balance, and the notion of an Integrative Education would be a challenging, but valuable context in which supra-curricular integration could take place. However, effective implementation of any model of Integrative Education need appropriate pedagogies, the key word here being appropriate. In achieving cultural balance the author has argued elsewhere , Thomas(1997, 2002) that both curriculum and pedagogy need to be the main building blocks of a Culture Sensitive Education, in which different pedagogies can be used to match different teaching and learning contexts. In future discussions on knowledge cultures in higher education, it may be useful to examine further what value some notion of a Culture Sensitive Education would have in achieving a meaningful and desirable balance for an Integrative Education curriculum. (v) Research management and staff development In this subsection two realities will be discussed that must be faced if an Integrated form of higher education is to succeed in the future. The first concerns research needs, priorities and their management, secondly the need for academic staff to be trained as part of on going staff 30 development policies to improve research potential, and thereby benefit teaching and learning in the new age of supercomplexity. Research, and research Management In East and South East Asia teaching has priority over research. The reasons being that (a) training is seen as the principal role of universities, research being of secondary importance (b) as a result, a research culture has been slow to take root, although this is starting to change ( c) in these days of accountability, the outcomes of teaching and training are more measurable. The latter reason shows the influence of globalisation in the form of increased managerialism and accountability which increasingly pervades higher education. An associated affect also linked to globalisation, is where a research presence exists, it tends to be applied rather than pure. When government funding supports research, it understandably targets projects that have a bearing on National Development. However, private funding towards research in many Asian Pacific Rim countries is now on the increase, Braddock (2002). This has lead to concerns that higher education ceases to be only source of legitimate knowledge . Increasingly, Hi Tech industries and multinational corporations are not only generating new knowledge, but provide research training, breaking the monopoly of universities, trends incidentally discernable in developed countries as well. Questions about research priorities and funding have implications for decisions relating to curricular design, knowledge cultures, methods of instruction and effective assessment, especially when these issues are part of a wider debate about integration and curricular balance. 31 Research both pure and applied are necessary if some form of Integrative Education is to be realised in the near future. The need for effective research management is now a reality for most universities, which should alert academics to address the issue constructively. Alternative sources of education and training for undergraduates and graduates alike, should nevertheless not be seen as a threat to the traditional role and status of universities, as it may be that another form of integration in the offing, which predicts new partnerships between higher education and the world of work.? It follows from this that management research is as important an enterprise as managing research. However, as Neave (2004) has pointed out, there is a clear need in most emergent economies, for capacity building for both types of enterprise. Staff Development In order that an Integrative Education is both balanced, integrated and delivered effectively, the role of academic staff development will be a key concern. Brew (2002) has argued convincingly in an article on “Research and the Academic Developer…”, there is a need to redefine the roles of staff and students for the future of higher education. The future culture of higher education will be one in which students are educated to make considered choices, to develop skills of inquiry and be able to predict uncertainties and attempt to resolve them. In the light of these possibilties, an Integrative Education would need to use Problem and Issue based approaches to teaching and learning, where suitable. To translate these ideas into action the need for staff development becomes key, and some of the points discussed above relating to the management of research, apply to sound career development in all areas of higher education. 32 Teaching in higher education is no longer a solely Mode 1 activity, it encompasses Mode2 and Mode 3 approaches as well. The emphasis on construction as opposed to knowledge transmission, of uncertainty and inquiry rather than blind acceptance, a stress on process rather than outcomes, Parker(2003), are skills that academic staff need to master if a truly Integrative Education is to be relevant and effective. Staff development therefore, needs to tackle these changes with vigour, and with periodic training programmes which emphasise the skills and competencies mentioned above. EPILOGUE However, we should not lose sight of the fact that teaching in higher education is not only about developing knowledge and skills, but that human qualities and dispositions are also important in the process, for these are also part of preparing students for the age of supercomplexity. 33 REFERENCES Altbach, P.(2002) Knowledge and Education as International Commodities:The collapse of the common good International Higher Education, 27, Summer, 6-8. Altbach,P.(2002a ) Perspectives on Internationalising Higher Education, International Higher Education, 28, Summer, 2-5. Barnett, R., Parry, G. & Coate, K.(2001) Conceptualising curriculum change, Teaching In Higher Education, 6,4, 435 – 449. Barnett,R.(2004) Learning for an unknown future, Higher Education Research and Development, 23, 3, 247 – 260. Barnett R.(2000) Realizing the University in an age of supercomplexity. Milton Keynes: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press. Barrie, S. & Prosser, M. (2004)Generic graduate attributes: citizens for an uncertain future, Higher Education Research and Development, 23, 3, 243 246. Braddock, R. (2002) The Asia Pacific Region, Higher Education Policy 15 291-311 Brew, A. (2002) Research and the Academic developer: A new agenda International Journal of Academic Development, 7,2 113 – 122. Bruner,J.S. The Culture of Education, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Bourner T (2004) The broadening of the higher education curriculum,1970 – 2002 : an ipsative enquiry Higher Education Review 36 2 39 – 52. Burn, B. (2002). General Education to Integrated Studies, Higher Education Policy, 15, 1-6 Corson, D.(1998). Changing Education for Diversity. Buckingham: Open University Press. 34 Easton. D.(1991) The division ,integration and transfer of knowledge In D.Easton &C.S. Schelling (Eds.) Divided Knowledge across disciplines, across cultures. Newbury Park: Sage p7-36. Hayhoe, R.(1996) Knowledge Across Cultures (Ed.) Ottawa: OISE Press, pp xvii – xxiii Introduction. Heckt,M.(1999) Mayan Education in Guatemala: A pedagogical Model and its Political Context, International Review of Education 45,3-4, 321 – 337. Gibbons, M.A.(1998) Commonwealth perspective on the globalisation of higher Education, In P. Scott (Ed). The globalisation of higher education Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press pp 70 – 87. Neave,G.(2002) Academic freedom in an age of globalisation. Higher Education Policy 15, 331-335. Neave, G. (2004) The Business of University Research Higher Education Policy 17, 1- 4. Neave ,G .(2002) Managing research or research management Higher Education Policy 15, 217-224. Neave, G. (2004) The Business of university research Higher Education Policy 17, 1 -4. Northedge, A. (2003) Rethinking Teaching in the context of Diversity Teaching in Higher Education 8, 1, 17 –32. Parker, J. (2003) Reconceptualising the curriculum:from commodification to transformation Teaching in Higher Education 8,4, 529 -543. Pincas. A.,(2002) Borderless Education: a new teaching model for United Kingdom higher education, In E. Thomas(Ed.), Teacher Education: Dilemmas and Prospects, World Yearbook of Education , London: Kogan Page, pp 227- 237. Scott, D.K.(2002) General Education for an integrative age, Higher Education Policy 15, 7-18. 35 Semali, L.M. (2002) Cultural perspectives and teacher education: indigenous pedagogies in an African context, In E.Thomas(Ed.), Teacher Education: Dilemmas and Prospects, World Yearbook of Education , London: Kogan Page, pp155 – 165. Thomas, E.(1997)Developing a culture sensitive pedagogy:tackling a problem of melding “global culture” within existing cultural contexts. International Journal of Educational Development, 17,13-26. Thomas, E.(2002) Toward a culture-sensitive teacher education: the role of pedagogical models, In E. Thomas(Ed.), Teacher Education: Dilemmas and Prospects, World Yearbook of Education , London: Kogan Page, pp 167- 179. Thomas, E. (2003).Strategies for Teacher Education and Training in the Context of Global Change- Plenary Paper given at the International Conference on Teaching and Teacher Education, Islamic International University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia September 16-18th,2003. Tight, M. (2003) The organisation of academic knowledge : a comparative perspective, Higher education 4, 46,389 – 410. Weiler, H.N. (1996). Knowledge, Politics,and the future of Higher Education: Elements of a worldwide Transformation, In Hayhoe,R.(Ed.) Knowledge Across Cultures Ottawa: OISE Press, pp 4-29 World Bank, (2000) Task Force on Higher Education and Society in Developing Countries: Higher Education and Society in Developing Countries: Peril and Promise. Washington D.C. : World Bank and UNESCO. E THOMAS INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1:11:2004 36 37