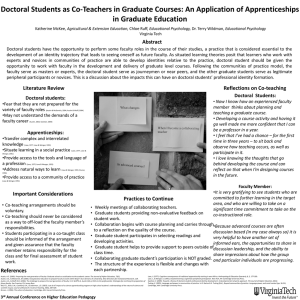

Cultural Theories of College-based Learning

advertisement

Towards a Cultural Theory of College-based Learning Phil Hodkinson[1], Gert Biesta[2] & David James[3] [1] University of Leeds, [2]University of Exeter, [3]University of the West of England A paper presented at the Annual Conference of the British Educational Research Association, Manchester, September 2004. Abstract This paper develops a cultural understanding of college-based learning, from a theoretical perspective. In doing so, we set out some of the ways in which such a perspective on learning differs from more well established views. We base our analysis on some of the principles established mainly in literature which addresses learning outside educational settings. This work suggests that individual learning is inherently embodied and social, and that learning may be valuably understood as a social practice. Following Bourdieu, we argue that learning should then be understood as cultural and relational. When this approach is applied to learning within a college, commonly expressed views about the differences between formal and informal learning become untenable, as are arguments that somehow college (or school) learning is inherently inferior to everyday learning, or learning at work. The paper then explores some of the implications of adopting a cultural perspective on learning. This includes problematising what counts as ‘good’ learning, and recognising that this varies from context to context, and from person to person. It is often contested. Implications for research include the need to see learning cultures as relational ‘wholes’, rather than searching for isolatable prime causes of learning. We conclude by raising some problems that the TLC project has encountered in operationalising this sort of theoretical stance, which is then further developed in then second paper in the symposium. Introduction Until relatively recently, the bulk of the literature on learning has shared four characteristics. Firstly, with the exception of the early learning of young children, it has concentrated on learning in educational settings, broadly defined to include schools, colleges and universities, together with adult education classes in diverse locations. Overall, schools dominate. Secondly, it has concentrated on learning as an almost exclusively individual activity, with the main theoretical roots located within psychology. Thirdly, it has adopted, either intentionally or implicitly, what Sfard (1998) terms the acquisition metaphor of learning. That is, learning is seen and understood as a process whereby knowledge is acquired. The crude version of this, what Bereiter (2002) terms the folk theory of learning, sees this process as a form of transmission – filling the vessel that is the student with the stuff that is to be learned, and with the teacher or lecturer acting as the conduit down which the stuff passes. The more sophisticated view sees the process of acquisition as one of construction. Here learning is conceived as requiring some major or minor adjustment to existing - usually cognitive - structures. This 1 sometimes entails ‘unlearning’ previous schemata, in order to allow the new knowledge to be properly understood. Fourthly, a dominant assumption is that learning is primarily concerned with the mind and with propositional knowledge, i.e., with rational thought, and with the ability to describe in words what it is that is known. Yet if our quest is to understand learning, the prevalence across a range of fields of an ‘acquisition of knowledge’ model can be criticised for what it cannot offer: ‘…the basic structural formula of learning, “transmit-internalize-transfer-apply,” presupposes the existence of special, secluded institutional arrangements. Nevertheless, this theory of learning does not allow us a full grasp of the significance of these institutional arrangements for leaning nor of learning in these arrangements’ (Dreier, 2001, p.23). For many years also, but especially more recently, views of learning that differ from this ‘standard paradigm’ (Beckett and Hager, 2002) have been developing. Empirically, they have been located primarily but not exclusively, outside mainstream educational settings, looking at what is often termed informal or everyday learning – learning found in the family, the local community, and the workplace. They see learning as social and move the centre of focus from the individual to the setting (community of practice or activity system) where learning is taking place. They share with constructivists the view that learning is a process, but see that broadly within what Sfard (1998) calls a metaphor of participation. That is, we learn through participating in activities, and/or through belonging to communities. Finally, these approaches see learning as embodied. That is, they are concerned with the practical and emotional, as well as the rational; with learning to do or to be, as well as learning to understand. Above all, they see learning as integral to all aspects of life – not some form of special process that is separate from the context in which it takes place, or which necessarily needs a teacher to function efficiently. Theories in this second group have been applied to learning in formal educational settings, but in limited ways, for example to critique formal education as an ineffective process (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Engestrom, 1991). In our view, this approach, though insightful, is dangerously partial, and leads to an unwarranted dismissal of formal educational learning as inherently inferior. In this paper, we examine the relevance of some of this second group of theoretical approaches to college learning in a hopefully more complete and certainly more positive way. Our reasons for wishing to do this derive from the research approach used in a major research project we are all engaged in – the Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education (TLC) project. Central to this project is a cultural understanding of learning. In what follows we outline the main tenets of our cultural approach to college-based learning, utilising key-insights from the second group of learning theories. The TLC Project 2 The TLC project is part of the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Teaching and Learning Research Programme (TLRP) (grant number L139251025). It is a four-year longitudinal study that takes a ‘cultural’ approach to learning in FE. We deliberately adopted a cultural perspective, because we believed teaching and learning, and the relationships between them, to be inherently complex and relational, rather than simple. Thus, our working assumption, now confirmed through the data collection and early analysis, was that all of the following dimensions would contribute to learning, and had to be examined in relation to each other: The positions, dispositions and actions of the students The positions, dispositions and actions of the tutors The location and resources of the site, which are not neutral, but enable some approaches and attitudes, and constrain or prevent others The syllabus or course specification, the assessment and qualification specifications and requirements The time tutors and students spend together, their interrelationships, and the range of other learning sites students are engaged with Issues of college management and procedures, together with funding and inspection body procedures and regulations, and government policy Wider vocational and academic cultures, of which any course or site is part Wider social and cultural values and practices, for example around issues of social class, gender and ethnicity, the nature of employment opportunities, social and family life, and the perceived status of FE as a sector. In order to examine the relationships between these dimensions, each of which is complex in its own right, we focussed on 16 learning sites, divided between four partner FE colleges1. The sites were selected through negotiation with the colleges, to illustrate some of the great diversity of FE learning, whilst, of course, not claiming to be representative of it. Changes since the project commenced extended the list to a total of 19 sites (see Hodkinson and James, 2003, for fuller details). One key tutor in each site worked with us as part of the research team. Data were collected over a three year period, in a variety of ways: repeated semi-structured interviews with a sample of students and with the tutors; regular site observations and tutor shadowing; a repeated questionnaire survey of all students in each site; and diaries or log books kept by each participating tutor. We also interviewed college managers, as and when relevant. The framing of the research owes much to the theoretical stance of Pierre Bourdieu. Although Bourdieu researched and wrote extensively on educational processes and their relation to wider social and economic matters, his work did not address learning in an explicit and direct sense. We wanted to explore the potential of his approach in understanding the cultural complexity of our learning sites. In what follows, we develop this approach further, drawing upon both the existing social/participatory literature about learning that was highlighted in the introduction, and on insights from pragmatism. The discussion that follows draws upon the overlapping but different academic backgrounds and theoretical preferences of the three authors of the paper, and also on the developing insights that are arising from the project thus far. Other papers in this symposium will 3 focus more directly on some our data, and our interpretation of them. We begin with a brief discussion of the notion of ‘culture’ and of how we wish to use it in our study of learning cultures and our cultural approach to learning. The Notion of ‘Culture’ in a Cultural Approach to Learning To make learning cultures an object of study and to put forward a cultural approach to learning requires some clarification of the notion of ‘culture’ – “one of the two or three most difficult words in the English language” (Williams 1983, p.87). Williams suggests three broad definitions. Culture as “a general process of intellectual, spiritual and aesthetic development,” culture as “a particular way of life, whether of a people, a period or a group,” and culture as “the works and practices of intellectual and especially artistic activity” (ibid., p.90). Our approach stays close to the second, anthropological definition of culture as a way of life. That is, we see culture as being constituted – that is, produced and reproduced – by human activity, often but not exclusively, collective activity. To think of culture as a practice constituted by the activities of those who make up the practice, does not necessarily entail an agency-driven view of culture, that is, a view which reduces culture to the intentions and actions of individual agents. As we will discuss in more detail below, Bourdieu’s notions of ‘habitus’ and ‘field’ are precisely meant to overcome the ‘either-or’ of subjectivist (agency) and objectivist (structure) readings of culture. What our approach does suggest, is that cultures exist in and through interaction and communication (see Biesta 1994; 1995; 2004; Carey 1992). From this it follows that a learning culture is not the same as a learning site. It rather is a particular way to understand a learning site, viz., as a practice constituted by the actions, dispositions and interpretations of the participants. This is not a one-way process. Cultures are (re)produced by individuals, just as much as individuals are (re)produced by cultures, though individuals are differently positioned with regard to shaping and changing a culture – in other words, differences in power are always at issue too. Cultures, then, are both structured and structuring, and individuals’ actions are neither totally determined by the confines of a learning culture, nor are they totally free. A key question that a cultural approach to learning brings to the fore is precisely that of the interplay between ‘constraints’ and ‘affordances’ in a learning culture (see Wertsch 1989, p.45). One of the most important implications of a cultural approach to learning is that learning culture is not seen as shorthand for the context or environment within which learning takes place. Rather, it is shorthand for the social practices through which people learn, or which themselves amount to learning. A cultural understanding of learning implies, in other words, that learning is not simply occurring in a cultural context, but is itself to be understood as a cultural practice. In what follows, we explore what thinking about learning in this way entails. First, we consider individual learners. 4 Individual Learning is Embodied and Social – and so is Teaching Long before the current wave of socio-cultural theories of learning, Dewey had argued strongly that learning was practical as well as mental (Dewey 1957; 1990; Biesta 1995). In Beckett and Hager’s (2002) terms, he challenged the Cartesian dualism that mind and body were separate, with the mind being the true location of human cognition, and mental/rational processes being superior to the emotional and the practical. When the focus is upon learning at work, the significance of this embodied view of learning is very clear. For much of what is learned at work entails practical activity, not just thinking. Beckett and Hager argue that this is a key weakness in Schon’s (1983, 1987) work on reflective practice – it over-emphasises the mind, as is implied in his use of the metaphor of reflection. Furthermore, Beckett and Hager (2002) argue that learning at work involves anticipation of the future, based upon accumulated experiences, not just reflection back. They prefer to think of this aspect of what they term informal learning as judgement making – which can be hot - almost instantaneous in the heat of action, or cold and more considered. But the judgments involve the whole person – emotions and practical activity, as well as the mind. The claim that people as learners are embodied is an ontological claim. That is, Beckett and Hager (2002) follow Dewey in arguing that people are inherently embodied – that the practical and emotional influence mental processes, and vice versa. It follows, therefore, that students and tutors in colleges are also embodied, and their learning should be considered as such. The embodied nature of learning is clearly shown in our data. For example, many college courses directly involve the practical as well as the mental. In the CACHE Diploma course, where mainly young women are trained as nursery workers, the emphasis was mainly on how to do the job, which was learned through a combination of doing it (both on placement and in college activities) and by thinking about what the work did and/or should entail, in discussions, group work and workshops. In all sites, there was a practical and emotional engagement with the learning as an activity that students participated in. Practical engagement might entail sitting at desks, writing notes, asking questions, and listening to the teacher (in AS psychology), as well as more obviously practical actions, such as editing a photographic image or speaking in a foreign language as in some other sites. Even in classes such as psychology, anyone who has observed learning will be aware of the physical and spatial nature of what goes on. At minimum, it can be seen in the ways people sit, move and interact, in the ways they use books, computers and pens. The emotional is also readily apparent. As well as indications of joy, boredom, frustration and even anger, in many sites there are deeper engagements. Thus, CACHE (Council for Awards in Children’s Care and Education) students were sub-consciously learning that emotional labour – a selfless giving of themselves whilst repressing their personal feelings, was required in the job, whilst entry level drama students were active in constructing their course as a second family – a place where they felt comfortable, and where tutors were pressured to adopt parenting roles. So college-based learning is embodied, even on the most ‘academic’ courses– such as psychology. 5 It logically follows that learning is also social. Firstly, the practices of learning and teaching themselves social. This is another key idea in the work of pragmatists like Dewey and Mead. It is especially Mead who shows in much detail that the social is not ‘outside’ the individual but exists in and through interaction, participation and communication (see Biesta 1999). Secondly, as Bourdieu points out, all people are socially positioned, at all times in their lives. Though he concentrates mainly on social class, the argument equally applies to issues of gender and ethnicity, of nationality or local community. Whilst this can be seen as part of social identity, Bourdieu prefers the term habitus. The habitus is a battery of dispositions to all aspects of life that are often sub-conscious or tacit. They develop from our social positions, and through our lives. The habitus can also be seen as social structures operating within and through individuals, rather than being something outside of us. This is another ontological claim, which closely parallels the non-Cartesian argument of the pragmatists. Just as mind and body are not separated, neither are the individual and social structures. The point is a very practical one for research in educational settings: work by Bloomer and Hodkinson (2000, 2002) shows how students as social individuals act upon the learning opportunities they encounter, and any courses they participate in. In Bloomer’s (1997) terminology, they construct their learning through studentship, and are not passive recipients of what tutors (or the system) tries to do to them. As Bloomer and Hodkinsons’s work also shows, life outside college can have a major impact on college learning. For whilst there may be a clear boundary around learning sites from the perspective of college timetable organisation, the social and embodied student often cannot make such a clear separation between their college learning and other parts of their lives. What applies to students also applies tutors. Just as Hodkinson and Hodkinson (2004b) found for schoolteachers, college tutors engage with work as social and embodied persons. They make judgements about how to teach and what to do, as Beckett and Hager (2002) describe. Our data provide many examples that illustrate this point. Tutors’ dispositions strongly influence the ways in which they approach teaching and their students, even leading them to go well beyond the formal job description (James and Diment, 2003). Some tutors challenged quite fundamental aspects of their practices as our fieldwork progressed, and one of our early project findings is that pedagogical changes sometimes entail significant shifts in a sense of identity. This is one way of understanding a well known truism that escapes the designers of teaching standards – what works for one teacher may not work for another, even in the same situation. The next stage in the cultural understanding of learning lies in changing the focus from the individual learner or teacher, to the social and cultural settings through which learning takes place. We do this by drawing upon some existing literature on situated learning, which considers learning as participation, rather than acquisition (Sfard, 1998). Situated Learning: Learning as Participation Work on situated learning became well known about 15 years ago. One of the first major thrusts in this work was the identification that learning was an inherently context-related 6 activity. Thus, Brown et al. (1989) argued that concepts, activities and context were always interrelated. Put simply, they argued that learning about using a chisel was different for a cabinet-maker and for a joiner, and that both were significantly different from such learning within a school (or college). In particular, they differentiated everyday learning from school learning, arguing that school learning, for example of mathematics, was based upon structured principles, whereas using number in work or at home was based on practical experience. They went on to argue that everyday learning was ‘authentic’, in the sense that concepts, activities and practices were in harmony with each other. In school, on the other hand, they claimed that there was a basic discordance between the subject matter to be learned, the activities to be engaged in, and the context where the learning took place. Lave and Wenger (1991) took this argument further. They used case studies of workplace learning in West Africa to focus upon the fact that many people in the world seemed able to learn without any formal schooling at all. In analysing what was happening in such learning situations, they argued that ‘In our view, learning is not merely situated in practice – as if it were some independently reifiable process that just happened to be located somewhere; learning is an integral part of generative social practice in the lived-in world.’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p.35) Two things follow from this view. Firstly, learning can take place anywhere, not just in educational establishments. Secondly, and more profoundly, there is no clear distinction between the process of learning, and other activities or processes with which people (including students) engage. They go on to argue ‘As an aspect of social practice, learning involves the whole person; it implies not only a relation to specific activities, but also a relation to social communities. … Learning only partly – and often incidentally – implies becoming able to be involved in new activities, to perform new tasks and functions, to master new understandings. Activities, tasks, functions, and understandings do not exist in isolation; they are part of broader systems of relations in which they have meaning. These systems of relations arise out of and are reproduced and developed within social communities, which are part of systems of relations among persons. … [Learning] is itself an evolving form of membership.’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p53) Put differently, the very thing that many educators and researchers into learning focus most attention on – the defined content to be taught and hopefully learned, is actually a small part of something much broader – learning to belong in whatever ‘community of practice’ a person participates in. Engestrom (2001, 2004) makes a similar point, but without the focus on communities of practice. For him, the key to understanding learning is to understand the activities learners are engaged in. He explains these activities through complex social and institutional systems, which he terms activity systems. Central to this point, from either Lave and Wenger’s or Engestrom’s perspective, lies the 7 move from viewing learning as acquisition of content, to viewing learning as participation (in a community or activity system). This does not mean that we cannot talk about what is learned, but it does entail seeing such outcomes as a part of something else, rather than the central raison d’etre of learning. Lave and Wenger (1991) are highly critical of school (and, by implication, college) as a location for learning. For if a college is seen as a community of practice, what students learn is how to belong to that college – how to be students, in other words. What they do not learn, according to Lave and Wenger, is how to be mathematicians, or plumbers or hairdressers. One way of expressing the problem that Lave and Wenger identify, is the clash between the content and outcomes of the official curriculum, and what Engestrom (2004, p151), following Bateson (1972), describes as ‘acquiring the deep-seated rules and patterns of behaviour characteristic of the context’. For Lave and Wenger, it is clear that the second type of learning is a pre-requisite for the first, which is the reverse of the more common position, which assumes that the knowledge is learned first, and then applied in practice. Furthermore, for learning to be truly effective, the two types must by synergistic (see also Dewey 1963; Biesta & Burbules 2003). This tension illustrates but also renders problematic a key distinction, drawn in much of the literature, between formal and informal learning. As Colley et al (2003a) show, this is a complex minefield of overlapping and even contradictory positions, yet it is usually seen in simple terms. College learning is generally thought of as ‘formal’. It is preplanned, intentional, often assessed: learning is the prime official objective of attending a college course. Everyday learning, on the other hand, is generally thought to be informal, in that it is often unintentional in the sense that people are not explicitly trying to learn but simply to cope with everyday tasks or problems. It is also often hidden or tacit, in the sense that people do not think they are learning at all. However, in informal learning, the argument goes, there is an ‘authentic’ relationship between what is learned, how it is learned, and the context in which learning takes place. For many writers from a situated learning perspective, this makes informal learning much more effective than anything that can be done in college. Yet, as Colley et al (2003a) show, this division between informal and formal learning breaks down upon closer examination. They argue that the terms formal and informal are attributed to learning by writers, in a variety of different, if overlapping ways. They also argue that what they term ‘attributes of in/formality’ can be found in all learning situations. Specifically, college and school learning is characterised by significant degrees of informality, which are every bit as important as any so-called formal attributes. Thus, Lave and Wenger’s (1991) sense of learning to participate as a student, and Engestrom’s acquiring deep-seated rules and patterns of behaviour, are exactly the sorts of learning process that are normally described as informal – but they takes place within school and college settings. In Colley et al,’s (2003a) terminology, some attributes of informality are important in colleges. 8 College Learning Sites as Communities of Practice One way of thinking about college learning from this situated perspective, is to consider each learning site as a community of practice. However, if we are to do this, we need first to move past some conceptual confusion in Lave and Wenger’s (1991) text, and Wenger’s (1998) subsequent work. Hodkinson and Hodkinson (2004a) argue that there are two different meanings in the text, and that each confuses the other. The broader more universal meaning can be derived from the quotes about learning already cited. From this perspective, Lave and Wenger (1991) are arguing that learning is a fundamentally social act. That is, we cannot learn without belonging to something – a something which they term a community of practice. Thus, ‘A community of practice is an intrinsic condition for the existence of knowledge. … Thus, participation in the cultural practice in which any knowledge exists is an epistemological principle of learning. The social structure of this practice, its power relations, and its conditions for legitimacy define possibilities for learning.’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p98, emphasis added). We return to this conception of community of practice later. However, most of the subsequent attention to Lave and Wenger’s work focussed upon a much narrower definition of community of practice. This can be seen in the examples they give, which are all of relatively close-knit groups of workers. This narrower view is captured by Wenger’s (1998) definition – that a community of practice exists where there is mutual engagement, joint enterprise and a shared repertoire of actions amongst its members. At first glance, many of our sample learning sites meet much of this narrower definition. Thus, in the CACHE Diploma site, all involved are mutually engaged in the joint enterprise of learning to become nursery nurses, whilst in AS French, they are mutually engaged with the joint enterprise of improving their linguistic ability and their associated understanding of French society and culture. In such sites. the repertoire of actions amongst students are also shared. However, if such sites are to be thought of as communities of practice, the differences in position, intention and actions of tutor and students cannot be underestimated. Engagement between tutor and students is different in kind from that between student and student; the enterprise of teaching and the actions of tutors are clearly different from the enterprise of learning and the actions of students even though the two are declared to be closely linked. Furthermore, if there is continuity within such a community over time, it lies mainly with the tutor. Students come and go, and one cohort is replaced by another. Consequently, in Lave and Wenger’s terms, a learning site community of practice is reconstructed every time an intake changes. The nature and extent of participation in a community of practice varies also. In some courses, tutor and students are present together almost on a fulltime basis. In others, they meet for a relatively short period of time every week. In some sites, it makes little sense to think about mutual engagement at all: learners may be engaged in very similar tasks and processes but be isolated from each other, in both the spatial sense of living and learning in different locations, and also in the social sense that they scarcely know of, let alone communicate with, each other. 9 Such difficulties around the concept community of practice explain one of the reasons why we use the term ‘culture’ in the title of this paper and the project. In Lave and Wenger’s (1991) work, communities of practice change when membership changes. Yet in many of the learning sites we are studying, there are strong elements of continuity that do not seem to be directly rooted in any individual or even group of individuals. That is, the culture of a site entails much more than the positions dispositions and inter-relations between participants at any one time. A learning culture persists in a latent form between the occasions on which it becomes most manifest or apparent. Put another way, there can be continuity because the tutor often remains in position, but there are also various ‘reified’ (Wenger, 1998) elements (textual and other learning materials, specifications from awarding bodies, assessment requirements, physical resources, organisational practices, relationships, logistical solutions) which will usually impose a good deal of structure on how things can be done. This means not seeing ‘participation’ as simply a metaphor for student and tutor activity, but recognising it as an instance of enactment and reproduction of social relations. The ‘field’ of Learning Wenger’s (1998) narrow notion of community of practice is thus too limited to fully encapsulate the cultures of our learning sites. However, there is greater mileage in the wider version of the concept in his earlier book with Jean Lave (Lave and Wenger, 1991) that has already been alluded to. As we have seen, in this wider version the two authors claim that belonging to a community of practice is an essential precondition for learning. This is combined with their very loose definition of a community of practice: ‘A community of practice is a set of relations among persons, activity, and world, over time and in relation with other tangential and overlapping communities of practice’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p98.) Thus, they are arguing that learning is an inherently social activity, and part of being a social human being is to belong to something. Community of practice is simply the term they use to describe what it is to which we belong. This is a very different position from that taken later by Wenger. With this wider definition, communities of practice do not have to possess any of his three defining characteristics at all. Hodkinson and Hodkinson (2004a) have argued that this wider version of community of practice resembles Bourdieu’s notion of ‘field’, and we will use the term ‘learning field’ in this paper, to distinguish this version from the narrower community of practice of Wenger. The concept of learning field helps us develop a cultural understanding of learning in several ways. Firstly, it reemphasises the point that learning is a social process, concerned with much more than just the individual learner. Next, it brings to the centre of the analysis the differing power relations between participants in a learning field, in ways that Lave and Wenger’s work does not. Also, it provides a vehicle for the integration of individual and social perspectives – something that few if any current theories of learning have achieved. (See Hodkinson and Hodkinson, 2004b, for further discussion of this 10 advantage, which we do not have space to fully explore here.) Finally, it makes it easy to conceptualise influences on learning from a variety of different scales or levels, for example seeing a learning site as defined not only by the localised setting of a particular teaching group, but also by the broader issues of college, national policy and social, economic and political pressures throughout society. How does it make these things possible? Bourdieu eschews a precise definition of field, and is unconcerned with identifying precise boundaries. Also, fields overlap. In particular, any specific field will always interrelate with what he terms the ‘field of power’ – the more macro structures and processes of inequality in society. Instead of a definition, Bourdieu uses two metaphors to describe what a field is (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992). The first is that of a market, and the second a game. A field is a ‘market’ in so far as it describes a social space of relationships that are unequal but mutually dependent, and where there is some competition. Individuals differ in the amount of ‘purchasing power’ they have because they have different backgrounds. This ‘purchasing power’ is not always monetary wealth, but may take the form of cultural of social capital (see below). This ‘market’ metaphor is useful up to a point, though the view of a field as a ‘game’ may be more helpful for our present purposes2. Bourdieu uses this metaphor to emphasise some key characteristics of a field. Thus, like a game, a field is in flux, not some static set of structural relations. Like a game, players in the field are striving to do well – both in their own terms, but also within the established rules of the game. He describes this as striving for distinction (Bourdieu, 1984), though this can take many different forms. As both market and game metaphors make clear, fields are conflictual as well as consensual. Like a game a learning field has rules, some of which are explicit – reified procedures, in Wenger’s (1998) terms. These might include college regulations, examination board specifications, and OFSTED inspection criteria. However, unlike many formal games, the rules of a field are also tacit and uncodified. They are determined in part by the players of the game, who construct the processes and procedures of the field through their participation in it. As in a literal game, the players are not equal. Linking back to the market metaphor, Bourdieu describes the roots of these differences and inequalities in two places. Firstly, people are unequally positioned in the field. In our sites, not only are tutors and students differently positioned, but also, students can be differently positioned from each other, as can be tutors, where more than one is involved. Secondly, such differences and inequalities relate to the levels and types of capital that players possess – which are, in turn, reciprocally related to the positions that they occupy. Bourdieu identifies three types, which overlap and are mutually exchangeable. Economic capital is the most straightforward, and equates with the financial resources different players possess. Economic capital impacts upon the learning of students, and on the teaching of tutors directly, but more importantly through its relations to social class. 11 Social capital, for Bourdieu, roughly equates to whom you know and who knows you. It is a way of expressing the advantages and disadvantages that come from social relations, including sponsorship or its opposite – marginalisation, discrimination or even exclusion. Social capital impacts upon learning within particular sites, in that who can belong, and the nature of their belonging (for example, friendship groups, and the relationships between tutor and students) are significant. This also connects with wider societal issues, as can clearly be seen in the feminine and working class nature of the CACHE Diploma site, as opposed to the more masculine engineering site (Colley et al., 2003b). The third, and arguably for Bourdieu most important, form of capital is cultural capital. This roughly equates to understanding how the game is played. People play such games largely within what Giddens (1991) terms ‘practical consciousness’. That is, people with high cultural capital possess ‘pre-perceptive anticipations, a sort of practical induction [to the future] based upon previous experience … [anticipations that] are the fact of the habitus as a feel for the game. Having the feel for the game is having the game under the skin; it is to master, in a practical way the future of the game; it is to have a sense of history of the game.’ (Bourdieu, 1998, p80). Put simply, those with superior positions and more capital not only have advantages in playing the game, or learning. They also have more influence on the rules that determine the nature of success, and what counts as capital or successful learning. Though these differences can be thought of at an individual level, Bourdieu seldom does that. He is more concerned with broader social and cultural differences. Thus, in relation to college learning, ‘players’ could include governments, college management, examination boards, OFSTED/ALI, NATFHE and, for some sites and courses, local employers – as well as the particular tutors and students involved. It should always be remembered that capital only has value in relation to specific fields. That is, like all other factors contributing to learning, it is relational. The only sense in which capital is more universal in nature, lies in its links with the wider field of power, which, as has already been explained, impinges on all other fields. Thus, issues such as social class, gender or ethnic inequalities are deep-seated across many if not all fields in contemporary British society. For Bourdieu, dispositions within the habitus strongly influence the ways in which people operate in a field. These dispositions influence their perceptions of the field and the actions they take within it. The Benefits and Implications of Adopting a Cultural Theory of Learning Implicit in the argument advanced thus far is the realisation that different theories of learning themselves construct and operate with different definitions of what learning is. 12 All such theories and definitions are of course human constructions, not simple representations of what is external to us as writers and thinkers. Thus far, we have argued that it makes best sense to see learners as embodied and social beings. Indeed, it is hard to conceive of them as being anything else. Mind is not separate from the body, and to be human is to be social. It then follows logically to see learning as a cultural practice. This entails a different definition of learning, from that often used in noncultural theories. A cultural understanding of learning needs to go beyond the assumption that learning has only to do with individual change and transformation (as, for example, in the ‘classic’ definition of learning as any permanent change that is not the result of maturation). When learning is seen as a cultural practice, the distinction between change and no change is arbitrary and far from clear. Much learning, if culturally understood, entails reinforcement and deepening (of understanding, of beliefs, of practices, of skills). Such learning may be passive or active on the part of the learner, at least in the sense that a learner may deliberately strive to learn, or learn simply by being there and taking part. Either way, learning is essentially a process of participation and construction (or reconstruction), not the transfer of knowledge or skills into the learner as vessel. Consequently a cultural approach to learning requires a theory of learning that is not simply individualistic but thoroughly social. In our view, such a social theory needs to accommodate issues of structure and position, as well as action and interaction, and Bourdieu’s thinking can help us do that. One of the benefits of understanding that learning is socially constructed, is that it allows us to focus on the nature of constructions of learning in FE and in different learning sites. Too often, educational writers, policy makers and practitioners see ‘learning’ as an inherent good. Yet learning is conceived and valued differently, within a particular learning field. On one level ‘learning’ is a descriptive concept that simply denotes particular processes. This, however, changes dramatically as soon as we focus upon actual learners in actual college situations. The point is that learners cannot be summed up as more or less motivated to learn in some general sense; they want to learn particular things (knowledge, skills), and they want to learn those things for particular purposes (such as personal development, qualifications, job prospects, etc.), and in particular ways. In Bourdieu’s terms: the players in a learning field might strive to do well, but they come with a range of different definitions of what ‘doing well’ means for them (see, e.g., the contribution to this symposium by Tedder and Biesta’s on young men’s motivations for learning computer skills). A similar point can be made about teachers’ perceptions of good or appropriate learning, as well as from an institutional angle: curricula, course aims and objectives, qualifications and examinations all express particular views about the kinds of learning that are valued and desired from the institution’s point of view. Funding agencies, policy makers, college managers, employers’ representatives and other interests may have yet other normative agendas about the purpose of learning in FE. The learning field, to put it differently, is partly constituted by the particular values and normative orientations of the players. While there may be some agreement and consensus about what constitutes ‘good’ or ‘worthwhile’ learning, there will also be different and even conflicting ideas about what counts as good learning. The struggle over the very meaning of learning is an integral part of a learning field. The recent 13 hegemony of credentialism and the economic imperative more generally, and the subsequent decline of the idea of learning for personal development is a good example of such a struggle that is relevant to FE. Struggles like this over the meaning of learning are not simply rhetorical. What counts as learning has real and direct implications for what can and cannot be learned. Operationalising a Cultural Theory of Learning A cultural approach to learning also has implications for research. If it is the case that a learning culture is a practice through which people learn, and if cultures are both structured and structuring, then there is little point in trying to identify and isolate prime causal factors that influence, shape or produce learning. Different factors and influences interact with each other, without any clear foundational starting point. (Of course, particular ‘starting points’ can be adopted for specific research purposes, but it must always be understood that to do so is a simplification that can easily lead to reductionism.) This is precisely the point made by Cole who argues that a cultural approach makes it possible to overcome “simplified notions of context as cause” (Cole 1996, p.139). Instead, research needs to try to understand how learning cultures come into existence and stay in existence, how they are produced and reproduced through interaction and communication, and what kind of learning takes place through participation in a learning culture. From a cultural point of view, a central question is what kind of learning becomes possible through participation in a particular learning field and also what kind of learning becomes difficult or even impossible as a result of participation. In short, how participation itself ‘shapes’ the opportunities for learning and therefore, the learning definitions that particular practices allow, or reproduce. Instead of a factorial model in which contextual factors are seen as input and learning is seen as output, a cultural approach calls for a transactional understanding of the relationship between learning cultures and learning, within a learning field (see Biesta & Burbules 2003). Whilst Bourdieu’s approach provides a conceptual framework within which to integrate a range of socio-cultural understandings of learning, our analysis also needs to get below the levels of generalisation implied in the above analysis. There are two challenges. The first concerns issues of specificity. Thus, for Bourdieu, the natural scale of analysis is pretty large. Had he ever addressed learning directly, he would almost certainly have seen the field in terms of education as a whole, as he did in the work with Passeron (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990). This leaves a key problem in that our data show significant differences between our sites, all within what we might crudely term the ‘FE learning field’. We consequently need to operationalise socio-cultural perspectives at a variety of levels. This is exactly what is suggested in our definition of a learning culture as the social practices through which people learn, since this allows for an approach which focuses on specific learning practices rather than on the field of FE as a whole – which, of course, is not to suggest that the boundaries of such learning practices are simple, obvious or clear-cut. Bourdieu would almost certainly have agreed with Lave (1996, p161-162) when she argues: 14 ‘There are enormous differences in what and how learners come to shape (or be shaped into) their identities with respect to different practices…Researchers would have to explore each practice to understand what is being learned, and how.’ However, whilst appearing to solve one problem, this presents us with its opposite – how can we say something more general about learning in FE, whilst still retaining the strong sense in which each learning site is distinctive? The next paper in this symposium takes up this challenge, in relation to the research evidence being generated in the TLC project. Conclusion In this paper, we have advanced some developing thinking about the nature of college learning as a cultural activity, the benefits of considering college learning in that way, and some possible means of developing such an approach in relation to the specifics of particular sites. Our argument is supported by three different types of claim. Firstly, we are building on recent thinking about learning, in claiming that it makes ontological sense to see it as holistic, embodied and social at the level of the individual, and also as an integral part of contexualised social practice. We use the term culture, to encapsulate both. Secondly, we are taking approaches to learning developed outside formal education, and applying them to college learning, to see what happens. In doing this, we are not assuming some simple and unproblematic transfer of concepts and processes, but asking two questions. Does this sort of thinking work in relation to college learning? If it does, how can/should such thinking be reconfigured in relation to that learning? Behind these questions lies a much bigger one. Is it possible or advantageous to consider workplace and college learning within the same broad theoretical lens? Put differently, is Billett (2002, p57) right, when he claims that ‘Workplaces and educational institutions merely represent different instances of social practices in which learning occurs through participation. Learning in both kinds of social practice can be understood through a consideration of their respective participatory practices. Therefore, to distinguish between the two … [so that] one is formalised and the other informal … is not helpful.’ Thirdly, our claims are and increasingly will be empirical. They are based upon the vast wealth of data collected in the TLC project, and the insights into learning in our 19 learning sites, which these data facilitate. At the time of writing, the process of analysing this empirical data is partway through. Many of the ideas presented here can already be broadly supported, and some of this empirical support will be presented in the other papers in this symposium. However, more still needs to be done to evaluate, refine and reconstruct the detail of our analysis. This work will continue, over the final year of the project. Notes 15 1 We chose the term ‘learning site’ for two principal reasons. Firstly, our knowledge of the English Further Education sector gave us reason to avoid using terms like ‘classroom’, ‘lesson’ or ‘course’ as if they would apply to a cross-section of the diverse work of the sector. Secondly, we wished to avoid any assumption that the spatial and temporal organisation of college provision would always equate with the ‘where’ of learning. A simple illustration of this might be where a student attends several scheduled classes each week, but still do most of their learning at home. 2 Because of the recent domination of certain types of market views within policies towards education, the ‘market’ metaphor carries some baggage that we wish to avoid. Consequently, we concentrate here on the metaphor of a game. References BATESON, G. (1972) Steps to an Ecology of Mind (New York: Ballantine Books). Bauman, Z. (1973). Culture as praxis. London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul. BECKETT, D. and HAGER, P. (2002) Life, Work and Learning: practice in postmodernity (London: Routledge). BEREITER, C. (2002) Education and the Mind in the Knowledge Age. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. London. BIESTA, G.J.J. (1994). Education as Practical Intersubjectivity. Towards a criticalpragmatic understanding of education. Educational Theory, 44(3), 299-317. BIESTA, G.J.J. (1995). Pragmatism as a Pedagogy of Communicative Action. In J. Garrison (Ed.), The New Scholarship on John Dewey (pp. 105-122). Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer BIESTA, G.J.J. (1999). Redefining the subject, redefining the social, reconsidering education: George Herbert Mead's course on Philosophy of Education at the University of Chicago. Educational Theory 49(4), 475-492. BIESTA, G.J.J. (2004). “Mind the gap!” Communication and the educational relation. In Charles Bingham & Alexander M. Sidorkin (eds), Foreword by Nel Noddings, No education without relation (pp. 11-22). New York: Peter Lang. BIESTA, G.J.J. & BURBULES, N.C. (2003). Pragmatism and educational research. BILLETT, S. (2001) Learning in the Workplace: Strategies for Effective Practice (Crow’s Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin). BILLETT, S (2002). Critiquing workplace learning discourses: participation and continuity at work. Studies in the Education of Adults, 34(1), 56–67. BLOOMER, M. (1997) Curriculum Making in Post-16 Education: the social conditions of studentship (London, Routledge). BLOOMER, M. & HODKINSON, P. (2000), Learning Careers: Continuity and Change in Young People’s Dispositions to Learning, British Educational Research Journal, 26 (5) 583 - 598. BLOOMER, M. & HODKINSON, P. (2002) Learning Careers and Cultural Capital: adding a social and longitudinal dimension to our understanding of learning, in R. Nata (ed) Progress in Education, volume 5 (Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science). 16 BOURDIEU, P. (1984) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (London, Routledge and Keegan Paul). BOURDIEU, P. (1998) Practical Reason. Cambridge, Polity Press. BOURDIEU P and PASSERON J-C (1990) Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, Second Edition (London, Sage). BOURDIEU, P. and WACQUANT, L.J.D. (1992) An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology (Cambridge, Polity Press). BROWN, J.S., COLLINS, A. and DUGUID, P. (1989) Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning Educational Researcher, 18 (1) 32-42. CAREY, J.W. (1992). Communication as culture. Essays on media and society. New York/London: Routledge. COLE, M. (1996). Cultural psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. COLLEY, H., HODKINSON, P. & MALCOLM, J. (2003) Informality and Formality in Learning: a report for the Learning and Skills Research Centre (London: Learning and Skills Research Centre). COLLEY, H., JAMES, D., TEDDER, M. & DIMENT, K. (2003) Learning as becoming in vocational education and training: class, gender and the role of vocational habitus, Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 471-497. DEWEY, J. (1957[1922]). Human nature and conduct. An introduction to social psychology. New York: The Modern Library. DEWEY, J. (1963[1938]). Experience and education. New York: Collier. DEWEY, J. (1990[1902; 1900]). The school and society. The child and the curriculum Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. DREIER, O. (2001) Learning in personal trajectories of participation, IN N. STEPHENSON, H. L. RADTKE, R. JORNA & H. J. STAM (eds) Theoretical Psychology – Critical Contributions. Toronto, Capitus University Publications ENGESTROM, Y. (1991) Non Scolae sed vitae discimus: toward overcoming the encapsulation of school learning, Learning and Instruction, 1, 243-259. ENGESTROM, Y. (2001) Expansive Learning at Work: towards an activity-theoretical reconceptualisation, Journal of Education and Work, 14 (1) 133 – 156. ENGESTROM, Y. (2004) The new generation of expertise: seven theses, in H. Rainbird, A. Fuller & A. Munro (Eds) Workplace Learning in Context (London: Routledge). GIDDENS, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity: self and society in the late modern age (Cambridge, Polity Press). HODKINSON, H. & HODKINSON, P. (2004a) Rethinking the Concept of Community of Practice in relation to Schoolteachers’ Workplace Learning, International Journal of Training and Development, 8 (1) 21-31. HODKINSON, P. & HODKINSON, H. (2004b), The Significance of Individuals’ Dispositions in Workplace Learning: a case study of two teachers, Journal of Education and Work, 17 (2) 167 – 182. HODKINSON, P. & JAMES, D. (2003) Introduction: Transforming Learning Cultures in Further Education, Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 55, 4, 389-406. JAMES, D. & DIMENT, K. (2003) Going Underground? Learning and Assessment in an Ambiguous Space. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 55, 4, 407-422 LAVE, J. (1996) Teaching, as Learning, in Practice Mind, Culture and Society, 3 (3) 149164). 17 LAVE, J. and WENGER, E. (1991) Situated Learning, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. SCHÖN DA (1983) The Reflective Practitioner, New York: Basic Books. SCHÖN DA (1987) Educating the Reflective Practitioner, San Francisco: Josey Bass. SFARD, A. (1998) On Two Metaphors for Learning and the Dangers of Choosing Just One, Educational Researcher, 27 (2) 4-13. WENGER, E. (1998) Communities of Practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. WERTSCH, J. (1998). Mind as action. New York: Oxford University Press. WILLIAMS, R. (1983). Keywords. London: Fontana. 18