romanov mystery solved - University of Mississippi Medical Center

advertisement

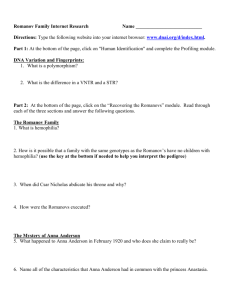

The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 Anastasia and Anna Anderson Anastasia's Family Grand Duchess Anastasia Nicholaevna was born on June 18, 1901. Her parents were Nicholas II, the last tsar of Russia, and his wife Alexandra. Anastasia had three elder sisters: Olga, Tatiana, and Maria. Her only brother, Alexei (often translated as "Alexis"), was born in 1904. For years Russia had been in upheaval. Anastasia's great-grandfather, Tsar Alexander II, freed the serfs and was known as the Tsar-Liberator, but in 1881 his carriage was bombed by a terrorist group called People's Will. Alexander was carried unconscious to the Winter Palace, where family members, including his thirteen-year-old grandson Nicholas, watched him die. Alexander II was succeeded by his son, Alexander III, Nicholas's father. Unlike his father, Alexander III believed in autocracy and opposed liberal reforms. He persecuted minorities, especially Jews. Nicholas grew up to be a kind and gentle young man. He spoke French, English, and German, and was an excellent dancer and horseman. But he was given little training for his future role as tsar. His father was still in his forties when Nicholas reached adulthood, and no one expected Nicholas to inherit the throne for many years. Nicholas's wife Alexandra was born Alix, Princess of Hesse-Darmstadt, the daughter of Princess Alice of England and Grand Duke Louis of Hesse. Alexandra was seen by many as cold and remote, but she had started life as a warm, happy child nicknamed Sunny. When Alix was six her mother died and Alix became withdrawn. For the rest of her life she appeared cool and aloof to those who didn't know her well. Alix was 12 and Nicholas 16 when they first met. Nicholas was smitten with Alix right away. When they were older they met again and fell in love, and in 1894 they became engaged. Soon after their engagement Alexander III died and 26-year old Nicholas became tsar. He said at the time, "I am not prepared to be a tsar. I never 1 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 wanted to become one." His first decree proclaimed Alix's new name, Alexandra Feodorovna. A week after Alexander III's funeral, Nicholas and Alexandra married. Nicholas and Alexandra were caring parents who spent a lot of time with their children. Anastasia and her sisters were close, and sometimes signed themselves collectively OTMA (their initials). The family lived quietly in the Alexander Palace at Tsarkoe Selo. This "simple" palace had over 100 rooms but was smaller than the nearby Catherine Palace, built by Catherine the Great to outshine Versailles. Anastasia as a Girl Anastasia was the youngest, most intelligent and most michievous of the tsar's daughters. She was an excellent mimic and enjoyed pranks and practical jokes. Anastasia's childhood playmate Tatiana Botkin described her as "lively and rough . . . roguish." Her cousin Princess Xenia described her as "frightfully temperamental, wild and rough." Years later Tatiana Botkin and Princess Xenia met Anna Anderson. Both believed that Anderson was Anastasia. But Anastasia had a gentle side. She was kind to her dogs: Shipka, who died of a brain disease, and Jemmy, a spaniel who died with the imperial family. And she was loving toward her sick brother. Few people outside the family knew that Alexei suffered from hemophilia, a disorder in which blood doesn't clot properly, causing internal bleeding. The smallest bump could cause Alexei agony, so he wasn't permitted play active games. Alexandra spent much of her time worrying about her son, who was unlikely to survive to adulthood. Anastasia had light brown hair (sometimes described as reddish blonde) and blue eyes. Like her mother and sisters she was a beauty, although as a teen she became rather fat. She shared a bedroom with her sister Maria, whom she dominated. Their room adjoined Olga and Tatiana's. The girls' quarters were separate from their parents'. They were raised relatively simply, bathing in cold water, sleeping on hard camp beds. The beds went with them everywhere, even to Germany when the girls visited their Uncle Ernst. They slept in these same beds until the night they died. 2 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 Like her sisters, Anastasia spoke English and Russian. Because of their isolation from the outside world, the girls' Russian was somewhat childish. Rasputin and the Revolution Nicholas II's reign lasted for over 22 years. He continued his father's policies of suppressing reform and persecuting minorities. His critics said that he listened too much to his advisors. Socialist groups agitated for the overthrow of the tsar's regime and the creation of a classless society. The Revolution of 1905 began when government troops fired on a crowd of workers who were marching to petition the tsar. This "bloody Sunday" caused peasant revolts, workers' strikes and naval mutinies. The Duma, a national parliament, was established, but it was hostile toward Nicholas and he dissolved it after 10 weeks. Later Duma conventions met the same fate. Meanwhile Alexandra was preoccupied with her attempts to help her sick son. She turned to Rasputin, a controversial holy man. Rasputin (1872-1916) had been born Grigori Yefimovich, the son of a Siberian farmer. As a young man Grigori was a drunken rake, so fellow villagers nicknamed him Rasputin, or "dissolute." One day Rasputin claimed to have received a vision from God. He became a wandering monk, apparently adept at healing. Rasputin did seem to have the power to help Alexei. One on occasion in 1912, when the tsarevich was on the verge of death, Rasputin sent a telegram saying, "The Little One will not die," and Alexei recovered. Rumors circulated about Rasputin's wild life when he was away from the imperial family, but Nicholas, Alexandra and their children trusted him completely, and he was always on his best behavior with them. Few people knew about Alexei's illness, so few understood why the imperial family chose to associate with the dirty, disreputable "mad monk." World War I began in 1914, and Nicholas personally took command of the Russian army the following year. In his absence Alexandra ran the government with Rasputin as her advisor. Many ministers resigned or were fired, and their posts filled by supporters of Rasputin. The government started to crumble. In 1916 a band of conspirators, including members of the imperial family, invited Rasputin to supper. According to the conspirators, they gave Rasputin poison, but it had no effect. They shot him and still he did not die. At last they tied him up and threw him into a river, 3 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 where he drowned. Rasputin was gone, but the damage he had done to image of the imperial family was irreparable. Disgusted by war losses and food shortages, workers in Petrograd and Moscow rioted. Mutiny spread through the military. On March 15, 1917 Nicholas was forced to abdicate. Captivity and Execution At the time of the abdication Anastasia and her siblings were suffering from measles. While they were confined to their beds the palace was taken over by soldiers. The imperial family were now prisoners. When the children recovered they went outside each day with their parents to walk in the park, where they were harassed and jeered. The imperial family had little peace during their months of captivity. Once, while sewing, Anastasia leaned repeatedly over a table. As she did so she moved back in forth in front of two colored lamps. Soldiers outside the window saw the lights flicker and thought she was sending signals to some outside accomplice. They burst in and searched the room, but of course found nothing. Eventually the imperial family was moved to Siberia. Their guards were rude and threatening. Anastasia and her sisters were not permitted to lock their bedroom door at night. Guards even followed the girls into the bathroom. The imperial family lived at Ipatiev House in Ekaterinburg for 78 days. Their last day was July 16, 1918. Late that night, the family was awakened and told to get dressed. After midnight they were taken to the cellar where, believing they were to be photographed, they stood in two rows. Anastasia, carrying her dog Jemmy, stood with her sisters, their doctor, and three servants. Suddenly armed men burst into the room and began firing. Anastasia's parents and sister Olga died at once, as did Dr. Botkin and two servants. But bullets bounced off Anastasia, Tatiana and Maria and ricocheted around the room. Unbeknownst to the men, the girls had sewn diamonds into their clothes so that they could smuggle them from place to place. This was what caused the bullets to bounce off them, but to the soldiers it appeared 4 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 miraculous. Astounded and scared, they kept firing. Tsarevich Alexei was on the floor, groaning but alive, so one soldier shot him in the head. It was a chaotic scene. The cellar was filled with smoke. Anastasia was seen huddled against the wall, covering her head with her arms. Eventually Tatiana and Maria died. A maid who did not die from the gunshots was bayoneted. By some accounts, Anastasia was also bayoneted many times. There is much confusion about how Anastasia died. Some people refuse to believe that she died at all. Anna Anderson The assassins did their best to destroy the bodies of the last imperial family and their attendants. First they were thrown down a mine shaft and grenades were tossed in after them. Later the corpses were removed from the mine shaft; some were burned, and others were doused with acid. The remains were thrown into a pit and buried. For decades, those who knew the location of the grave kept quiet for fear of the Soviet government, and rumors arose that one or more of the children had survived. Several supposed Anastasias surfaced over the years. One, Eugenia Smith, was still alive in the 1990s. The most famous Anastasia was Anna Anderson. On the night of February 17, 1920, less than two years after the murders in Ipatiev House, a woman jumped off a bridge in Berlin. She was rescued and taken to a hospital. She had no ID and refused to give her identity. She was sent to a mental asylum. There someone recognized her as Grand Duchess Tatiana. She didn't deny this right away, but eventually said, "I never said I was Tatiana." When she was given a list of the tsar's daughters' names, she crossed out all except Anastasia. When one of Alexandra's ladies-in-waiting visited her, the woman hid beneath a blanket. The lady-in-waiting called her an imposter and stormed off. But there were some who believed the woman's tale, and after her release in 1922 she lived on the charity of various sympathizers. Eventually she explained her escape from the imperial family's assassins. She had been bayoneted, she said, but survived because the soldiers' weapons were blunt. After the murders a soldier named Tschaikovsky saw 5 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 that she was still moving. During the chaos of that night he rescued her. Anderson said Tschaikovsky took her to Romania. Her story was confused, but it seems that at some point she may have married Tschaikovsky. After he was killed in a street fight she gave birth to his son, who was placed in an orphanage. The woman walked to Berlin to seek out "her" aunt, Princess Irene. (Scoffers asked why she hadn't sought out her parents' cousin, Queen Marie, while she was in Romania.) She reached the palace where Irene lived, but, fearing no one would recognize her, didn't try to enter. Instead she decided to commit suicide by jumping off the bridge. Princess Irene did meet the woman eventually and denied that she resembled Anastasia. Yet Irene later cried about the meeting and admitted, "She is similar, she is similar." Irene's son Prince Sigismund, a childhood friend of Anastasia, sent the woman a list of questions. Her answers convinced him that she was Anastasia. The woman, who began calling herself Anna Anderson in the 1920s, attracted many supporters and many deniers. Crown Princess Cecilie, the daughter-inlaw of the former kaiser and a relative of Anastasia, came to believe that Anderson was the lost grand duchess. Cecilie's son Prince Louis Ferdinand and his wife, Princess Kyra, did not believe. One of Anastasia's aunts, Grand Duchess Olga, met Anderson several times. Her opinion wavered, but finally she declared Anderson was not Anastasia. Anastasia's tutor, Pierre Gilliard, also met Anderson and thought she might be Anastasia. Later he changed his mind and called her "a first rate actress." Former ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska, who had been Nicholas's mistress before his marriage, and who later married Nicholas's cousin, Grand Duke Andrew, believed Anderson was Anastasia. She said Anderson had Nicholas's eyes, and looked at her with "the emperor's look." After spending two days with Anderson, Nicholas II's cousin Grand Duke Alexander exclaimed, "I have seen Nicky's daughter! I have seen Nicky's daughter!" Other staunch supporters included Anastasia's cousin Princess Xenia, and Gleb and Tatiana Botkin, whose father was murdered with the imperial family. Gleb's childhood drawings of animals in court dress had 6 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 delighted Anastasia. When he first met Anderson she asked about his "funny animals," convincing Gleb that she was Anastasia. Anderson also claimed to have startling knowledge about Anastasia's uncle, Grand Duke Ernst of Hesse. She said he had visited Russia in 1916, when his country and Russia were at war. Ernst angrily denied making the visit, but the kaiser's stepson testified in court in 1966 that he had been told Ernst did secretly made the trip. If this was true, how did Anna Anderson know about it? Determined to prove that Anderson was an imposter, Ernst backed an investigation that suggested Anderson was a Polish factory worker, Franziska Schanzkowska, who disappeared right before Anna Anderson surfaced. Some believe the investigation was tainted because the woman who identified Anderson as Schanzkowska was paid for her testimony. Although she depended on the good-will of her supporters, Anna Anderson was haughty and demanding, often arguing with her hosts. At times she attacked people or ran around naked. Her supporters pointed out it was not surprising Anastasia would have mental problems after watching her family die and being nearly murdered herself. Her detractors pointed out that she never spoke Russian. However, when she was addressed in Russian she understood and answered in other languages. She said she wouldn't speak Russian because it was the language spoken by those who had killed her family. She spoke good English, German and French - unusual for a Polish factory worker. She had scars that she said came from being shot and bayoneted. Her detractors said that the scars came from dropping a grenade when she worked in a munitions factory. Anderson and Anastasia had other physical similarities. Anderson had a foot deformity like Anastasia's. Anthropologists who studied their photographs found their faces to be very similar. One famous anthropologist, Dr. Otto Reche, testified in court that Anastasia and Anna Anderson had to be either the same person or identical twins. Anderson brought suit in a German court in 1938 to prove her identity and claim part of an inheritance. The case dragged on until 1970. Reche's testimony, made after examining photographs of Anastasia and Anna 7 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 Anderson, came in 1964. A handwriting expert, who was not paid for her testimony, also swore that Anderson was Anastasia. Anderson even tried to obtain samples of Anastasia's fingerprints for comparison, although this proved impossible. Finally the court ruled, not that Anderson wasn't Anastasia, but that she hadn't proved it. But experts continued to take Anderson's side. In 1977 a prominent forensic expert, Dr. Moritz Furtmayr, identified Anderson as Anastasia. For the last 15 years of her life Anderson was married to wealthy American John Manahan. She died of pneumonia in 1984 and was cremated at her own request. Her husband carried out her wishes and saw to it that her ashes were scattered in the cemetery at Castle Seeon in Germany, which was owned by distant relatives of the Romanov family. Recent DNA analysis of hair and tissue samples from Anderson seemed to prove that she was not Anastasia, but Franziska Schanzkowska. But some of Anderson's supporters cling to hope, saying that the tissue tested was not really Anderson's. They believe Anna Anderson - Anastasia - was swindled out of her true name and inheritance. The Romanov’s Remembered The remains of the imperial family were exhumed in 1991. Portions of nine skeletons were found, and DNA testing confirmed they included Nicholas, Alexandra, and three of their daughters. Two bodies remain missing. The consensus is that they are those of Alexei and one of his sisters, possibly Anastasia. On July 17, 1998, eighty years after the assassination, the imperial family and those who died with them were buried in the St. Catherine Chapel of St. Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg. Russian president Boris Yeltsin and members of the Romanov family attended the funeral, but senior members of the Russian Orthodox Church refused to attend due to lingering doubts over the identity of the remains. As tsar, and even after he abdicated, Nicholas II was the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. After the assassination, he and his family were revered by many as martyrs and numerous miracles were attributed to them. The family was canonized as royal martyrs by the Russian Orthodox Church 8 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 Abroad in 1981. In 2000, the Archbishops' Council of the Russian Orthodox Church voted unanimously to canonize Nicholas, Alexandra, and all of their children as passion bearers, a minor form of sainthood that recognizes the Christian humility and patience with which they endured their captivity. ROMANOV MYSTERY SOLVED Nine skeletons found in a shallow grave in Ekaterinburg, Russia, in July 1991 were tentatively identified as being the remains of the last Tsar, Tsarina and three of their five children - the Romanov family. It is believed that shortly after the night of 16th July 1918, Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Tsarina Alexandra and their five children Olga, Tatyana, Maria, Anastasia and Alexei were executed by the Bolsheviks. Their bodies were to have been transported to a mine shaft where they would have been disposed of however, the truck transporting them developed a mechanical fault along the way and so a shallow grave was hastily dug on the roadside and the bodies buried in un-consecrated ground. Despite extensive forensic evidence being collected, the version of events described above had never been positively verified and in 1992 the Forensic Science Service was approached by the Russian authorities to initiate an Anglo-Russian investigation to verify the authenticity of the remains using DNA analysis. Using samples taken from the surviving bones, the FSS performed DNA based sex testing and short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, the results of which confirmed that a family group was present in the grave. In addition a further testing technique was employed analysing Mitochondrial DNA (MtDNA). Mitochondrial DNA is a tiny amount of the total DNA present and can therefore be used when samples are too small, old or degraded for analysis by normal means. Where there is no body fluid or tissue available, Mitochondrial DNA can be taken from bone. MtDNA is more likely to survive for prolonged periods than chromosomal DNA and is particularly suited to 9 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 tracing maternal inheritance and testing relatedness if there are several generations between ancestor and living descendant. Following this extensive analysis, the FSS concluded that the DNA evidence produced supports the hypothesis that the remains are those of the Romanov family. DNA Test Confirms Dead Czar's Identity Science News, April 20, 1996 A new genetic analysis may finally allow former Russian Czar Nicholas Romanov II to rest in peace. On the night of July 16, 1918, a firing squad of Bolshevik soldiers executed the Russian royal family, including Nicholas, and buried the bodies in a hidden mass grave. The burial site finally came to light in 1989, and 2 years later nine skeletons were excavated. Though forensic analyses of the bones, clothing, and other material from the grave have provided b evidence that some of the skeletons belonged to the czar and his family, attempts to confirm the identifications by analyzing DNA samples have provoked controversy. When researchers compared DNA from bones presumed to be those of Nicholas II with DNA from two living relatives, they found an unusual mismatch. DNA is composed of long sequences of building blocks called nucleotides, which come in four forms that geneticist’s label A, C, G and T. The bits of DNA from the skeleton and Nicholas II's relatives matched perfectly except at one position. At a nucleotide site where both living relatives had a T, some of the DNA samples from Nicholas' bones had a T but others had a C. Such a variation is a rare condition called heteroplasmy. Despite the difference, investigators proclaimed that Nicholas had been identified. Yet the Russian Federation government and the Russian Orthodox Chruch, which is considering canonizing the entire Romanov family, demanded further proof. In July of 1994, researchers resorted to exhuming the body of Georgij Romanov, Nicholas' younger brother, who had died of tuberculosis in 1899. 10 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 Like Nicholas's DNA, Gerogij's had either C or T present at the controversial site, report Pavel L. Ivanov of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow and a team from the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory in Rockville, Md., led by Thomas J Parsons. The team describes its findings in the April Nature Genetics. The heteroplasmy, says Parsons, must have disappeared somewhere in the generations after Nicholas. An editorial in Nature Genetics notes that this is the first time heteroplasmy has been used to aid identification. "To me, this is the nail in the lid. It's the most convincing argument I've seen," adds William R, Maples of the University of Florida in Gainesville, who had suggested earlier that Nicholas' apparent heteroplasmy resulted from contamination of the DNA samples. Why Are Alexei's Bones Absent? By John Kendrick The St.Petersburg Times In the 80 years since the Romanov's deaths, numerous pretenders have claimed to be a member of the imperial family who miraculously survived. Sooner or later, their claims were debunked, but as John Kendrick reports, the claims of one man who never publicly pushed his case while alive have yet to be convincingly disproved. VANCOUVER, Canada - A world of controversy surrounds the identity of the remains to be interred this Friday in St. Petersburg, but one matter is not in dispute. The remains of Tsarevich Alexei, Nicholas II's only son and heir, will not be among those laid to rest. 11 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 Half a world and 11 time zones away from the former imperial capital, there is a grave where a man known as Alexei Tammet-Romanov was buried 21 years ago, soon after his death on June 26, 1977, which followed a two-year battle with a mysterious blood disease. On July 2, 1977, an obituary marked by the Romanov crest of the imperial double eagle ran in the Vancouver Sun stating that, "Alexei Nicolaievich, Sovereign Heir, Tsarevich, Grand Duke of Russia," had died June 26. On page 62 of its July 5 edition, the same paper reported that Tammet-Romanov's widow, Sandra, intended to write a book on her late husband's life. Within a month, the Ipatiev House where the Bolsheviks executed Nicholas II was gone, demolished by the governor of the Sverdlovsk region, one Boris Yeltsin, at Leonid Brezhnev's order. Tammet-Romanov never publicly claimed to be the tsarevich. When 16-year-old Sandra Brown met 52-year-old Heino Tammet on a beach in 1956, she had no idea that the man she would marry four years later was anything more than an Estonian immigrant who ran a small dance studio. Mrs. Romanov explained that when she met Alexei it was her father who first sensed that there was something unusual about the man calling himself Heino Tammet. In the beginning he would only tell them that, "as a youngster I lived in many houses," although he was not beyond dropping an occasional, broader hint. When pressed, he said that he was the Tsarevich Alexei Romanov, who had survived the bloodbath at Ipatiev House on July 17, 1918, when the rest of his family were killed. After Alexei had escaped the fate of his parents and sisters, he and the Veermann family who took care of him stayed at their farmhouse close to Yakaterinburg before moving to the Estonian capital of Tallinn in September 1921. He lived in Tallinn for the next 22 years, the same town where a boy named Alexy Mikhailovich Ridiger was born in 1929. Alexy Ridiger grew up to become His Holiness Patriarch Alexy II. 12 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 Tammet-Romanov used the name of Ernst Veermann until 1937, when he changed it to Heino Tammet. As Heino Tammet he operated seven newspapers in Tallinn as editor-in-chief, before fleeing the advancing Red Army in early 1944. He moved to Sweden, before emigrating to Canada in 1952. According to Mrs. Romanov, Alexei explained that he blacked out after hearing Yakov Yurovsky - the head of the execution squad - give the command to fire. He woke up almost three days later at nearby farm house belonging to Johann and Paula Veermann. Alexei was told that Johann Veermann was on the road with his farmer's cart when he happened upon the assassins' truck stuck in the mud possibly at the same spot where geologist Alexander Avdovin discovered in 1979 the remains that will be interred this Friday. Veermann told Alexei that he was asked to take two bundles wrapped in sheets off the truck to lighten its load and take them to a nearby pit. When one of the bundles moved he took it home, and found the injured Alexei wrapped inside the sheets. What exactly happened will probably never be known, but the official versions of the killings leave much to be desired. The firing squad of 11 to 13 men (official versions vary on the number of assassins) are said to have emptied their weapons at the party of 11 - Romanovs and servants - yet those who examined the remains and the house found evidence of far fewer than the 80-plus bullets that would have been loaded into the guns used by the firing squad. Then there are the bizarre assertions that bullets bounced off diamonds and jewels sewn into the grand duchesses' corsets. Yurovsky later claimed that his deputy, Grigory Nikulin, emptied an entire clip of bullets at the girls and Alexei with no effect. This story does not fit with an understanding of basic physics. The force of a bullet fired at near point blank range and striking a diamond or similar stone dead center would either shatter the stone or push it into the soft cloth and flesh situated directly behind it. If the bullet struck the stone offcenter then it might change direction slightly but it would still pass some of the energy of its forward momentum onto the jewel it struck. Anyone who has played a game of billiards knows how this works. Then there is the medical evidence. Execution squad commander Yurovsky fired two shots at the right ear of Tsarevich Alexei. Alexei Tammet-Romanov was completely deaf in that same ear. Doctors thought the injury was caused by some kind of concussion accident, such as a very loud noise, during his youth. 13 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 Adding that evidence to executioners' stories that the bullets they fired at the young Grand Duchesses were having no effect suggests a new possibility. Execution squad commander Yurovsky loaded the guns himself before handing them out to his hand-picked firing squad. Each assassin was told to fire at a certain member of the Imperial party. If Yurovsky had loaded some of the guns with blanks that would explain how guns fired at the Grand Duchesses had no effect. It would also explain how a gun fired at the ear of Alexei would make him deaf in that same ear, but would not kill him. At the height of the civil war Lenin was faced with the problem of 11 imperial hostages that were attracting a lot of attention. Might the Bolshevik leaders have looked for a way to reduce the number of hostages but keep the one who was the most politically important? The identity of Alexei Tammet-Romanov's foster mother, Paula Veermann, may provide a clue. Her maiden name was Paula von Benckendorff-Kanna. Research into the genealogy of the Benckendorff family has suggested that Paula may have been related to Count Paul Benckendorff, Grand Marshall of the Tsar's Imperial Court. Count Benckendorff was known to have led the efforts to find the Romanovs a place of exile or rescue right up to the time of the murders. Then there is the matter of the tsarevich's health. Historians have always suggested that Nicholas II's only son suffered from hemophilia, but no actual proof of that diagnosis is known to exist. The only official statement on the disease from the tsar's doctors described the boy's symptoms as "significant anemia." It took six months for Tammet-Romanov's Vancouver doctors to identify the disease that eventually took his life. They decided it was a form of leukemia. Throughout those last two years, Tammet-Romanov displayed the same symptoms that struck down Tsarevich Alexei during a visit to the tsar's hunting lodge at Spala in Poland in October 1912. The key to the true nature of Alexei's disease can be found in a letter that Nicholas II wrote to his mother. "The days from the 6th to the 10th were the worst ... His high temperature made him delirious night and day." 14 The Mystery of the Russian Royal Family Susan A. Bender 2005 An episode known to modern medicine as thrombocytopenia produces the same symptoms of hemorrhaging and fever that struck down the tsarevich and is known to occur in child and adult patients with leukemia and aplastic anemia. If thrombocytopenia does not kill the patient first it can instead go into spontaneous remission - which could explain Rasputin's alleged power to "heal" the tsarevich. Modern medicine also has greater knowledge on methods of identification. In 1994, British expert Peter Gill announced that DNA matching techniques at the Forensic Science Service Research Laboratory in Aldermaston, England, had shown that the woman known as Anna Anderson, who had long claimed to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia, could not have been related to Nicholas II or Empress Alexandra. Gill and Russia's molecular biologist Dr. Pavel Ivanov were the researchers who first used DNA to verify the identity of the bones to be interred Friday. Two of Alexei Tammet-Romanov's teeth extracted in 1962 were sent in April 1993 at Ivanov's request to the Adermaston laboratory. Ivanov admitted in a 1995 letter to Tammet-Romanov's widow that a DNA extraction was started on her late husband's DNA samples while the identification of the remains found near Yekaterinburg was being done at the English laboratory in 1993. He told her that shortly after that "we were forced to stop all the tests on any potential survived Romanov claimants." He did not explain why the tests were stopped. In the five years since DNA extraction was started on one of Tammet-Romanov's teeth, no one has said if the tests were ever completed. Neither has any person connected to the investigation of the murders of the Imperial Family been willing to say anything about the man buried in a Vancouverarea cemetery and whether or not he really could have been the missing Tsarevich Alexei Nicolaievich, Grand Duke and Sovereign Heir to Russia's throne. 15