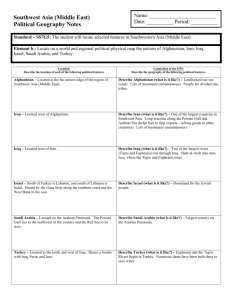

Global Studies

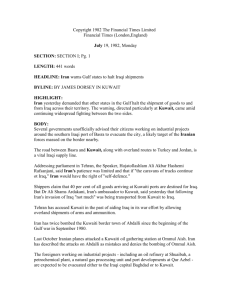

advertisement