Genome 10K: A Proposition to Obtain Whole Genome Sequence For

advertisement

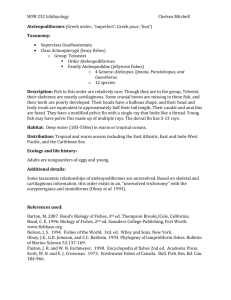

LGDMSNO09700 May 4, 2009 Journal of Heredity NB: please do not reformat reference w/ EndNote without checking Bob’s edits to the lit. cited section. Genome 10K: A Proposition to Obtain Whole Genome Sequence for 10,000 Vertebrate Species Genome 10K Community of Scientists Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 4 Proposal .......................................................................................................................... 7 Mammals......................................................................................................................... 9 Birds .............................................................................................................................. 10 Reptiles ......................................................................................................................... 11 Amphibians ................................................................................................................... 12 Fish ............................................................................................................................... 13 Discussion ..................................................................................................................... 15 Methods: ....................................................................................................................... 18 Appendix 1: Policy issues.............................................................................................. 19 Appendix 2: Detailed table of classes, orders, families, genera and species ................ 20 Appendix 3: Technological issues ................................................................................. 24 Authors: ......................................................................................................................... 25 References: ................................................................................................................... 26 Table 1: Vertebrate taxa ................................................................................................ 29 Table 2: List of collections and participating institutions (Fill this in) .............................. 30 Figure legends (need these) (Fill in references) ............................................................ 33 Figure 1: A phylogenetic view of the vertebrate subclass.............................................. 34 Figure 2: The mammalian radiations ............................................................................. 35 Figure 3: The birds of the world ..................................................................................... 36 Figure 4: The reptiles of today ....................................................................................... 37 Figure 5: The amphibians’ phylogeny............................................................................ 38 Page 2 Abstract The human genome project was recently complemented by whole genome sequencing assessment of 32 mammals and 24 non-mammal vertebrate species suitable for comparative genomic analyses. Here, we anticipate the precipitous drop in sequencing costs and the development of greater annotation technology by proposing to create a collection of tissue and DNA specimens for 10,000 vertebrate species specifically designated for whole genome sequencing in the very near future. For this purpose we, the G10K Community of Scientists, assemble and allocate a collection of some 16,000 representative vertebrate species spanning evolutionary diversity across living mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fishes (circa 60,000 living species). With this resource, the biological science community for genome sequence assessment may now pursue the opportunity to usher in a new era of investigation in the biological sciences, embark upon the most comprehensive study of biological evolution ever attempted, and invigorate genomic inference into every aspect of vertebrate biological enquiry. Page 3 Introduction The bold insight behind the success of the human genome project was that, while vast, the roughly three billion bits of digital information specifying the total genetic heritage of an individual is finite and might, with dedicated resolve, be brought within the reach of our technology [1] [2] [3]. The number of living species is similarly vast, estimated to be between 106 and 108 for all metazoans, and approximately 6 x 104 for the subphylum vertebrata, the evolutionarily closest relatives to humans. With that same unity of purpose, we can now contemplate reading the genetic heritage of all species, beginning with the vertebrates. The feasibility of a “Genome 10K” project to catalog the diversity of vertebrate genomes requires but one more order of magnitude reduction in the cost of DNA sequencing, following the four orders of magnitude reduction we have seen in the last 10 years. It is time to prepare for this undertaking. Living vertebrate species derive from a common ancestor that lived roughly 500 million years ago (Ma), near the time of the Cambrian explosion of animal life. Because a core repertoire of about 10,000 genes in a genome of about a billion bases is seen in multiple, deeply-branching vertebrates and close deuterostome out-groups, we may surmise that the haploid genome of the common vertebrate ancestor was already highly sophisticated; consisting of 108 - 109 bases specifying a body plan that includes segmented muscles derived from somites, a notochord and dorsal hollow neural tube differentiating into primitive forbrain, midbrain, hindbrain and spinal chord structures, basic endocrine functions encoded in distant precursors to the thyroid, pancreas and other vertebrate organs, and a highly sophisticated innate immune system [4-8] [9] [10]. In the descent of the living vertebrates, the roughly 108 bases in the functional DNA segments that specify these sophisticated features, along with more fundamental Page 4 biological processes, encountered on average more than 30 substitutions per nucleotide site, the outcome of trillions of natural evolutionary experiments. These and other genetic changes, including rearrangements, duplications and losses, spawned the diversity of vertebrate forms that inhabit the planet today. A Genome 10K project explicitly detailing these genetic changes will provide an essential reference resource for an emerging new synthesis of molecular, organismic, developmental and evolutionary biology to explore the forms of life, just as the human genome project has provided an essential reference resource for a new biomedicine. Beyond elaborations of ancient biochemical and developmental pathways, vertebrate evolution is characterized by stunning innovations, including adaptive immunity, multi-chambered hearts, cartilage, bones and teeth, an internal skeleton that has given rise to the largest aquatic and terrestrial animals on the planet, and specialized endocrine organs such as the pancreas, thyroid, thymus, pituitary, adrenal and pineal glands [11]. At the cellular level, the neural crest, sometimes referred to as a fourth germ layer, is unique to vertebrates and gives rise to a great variety of structures, including some skeletal elements, tendons and smooth muscle, neurons and glia of the autonomic nervous system and aspects of the sensory systems, melanocytes in the skin, dentin in the teeth, parts of endocrine system organs, and connective tissue in the heart [12, 13]. Sophisticated vertebrate sensory, neuroanatomical and behavioral elaborations coupled with often dramatic anatomical changes allowed exploitation of oceanic, terrestrial, and atmospheric ecological niches. Anticipated details of expansions and losses of specific gene families revealed by the Genome 10K project will provide profound insights into the molecular mechanisms behind these extraordinary innovations. Page 5 Adaptive changes in non-coding regulatory DNA also play a fundamental role in vertebrate evolution and its understanding represents an even greater challenge. Almost no part of the non-coding vertebrate gene regulatory apparatus bears any discernable resemblance at the DNA level to analogous systems in our deuterostome distant cousins, yet the apparatus occupies the majority of the bases we find to be under selection in vertebrate genomes, and is hypothesized to be the major source of evolutionary innovation within vertebrate subclades [14] [15] [6] [16]. The origins and evolutionary trajectory of the subset of non-coding functional elements under the strongest stabilizing selection can be traced deep into the vertebrate tree [17], in many cases to its very root, while other non-coding functional elements have uniquely arisen at the base of a particular class, order or family of vertebrate species. Within vertebrate clades that evolved from a common ancestor in the last 108 million years, such as mammals (5000 species), modern birds (10,000 species), Anura (5,700 frog and toad species), Acanthomorpha (16,000 fish species), snakes (3000 species), geckos (1000 species) and skinks (1300 species), evolutionary coalescence to a common ancestral DNA segment can be reliably determined even for segments of non-coding evolving DNA. This enables detailed studies of base-by-base evolutionary changes throughout the genome, in both coding and non-coding DNA [14]. With an estimated neutral branch length of about 20 substitutions per site within such clades, the Genome 10K project provides enormous depth of genome-wide sequence variation to address critical hypotheses concerning the origin and evolution of functional non-coding DNA segments and their role in molding physiological and developmental definitions of living animal species. Page 6 Proposal To this end, we propose to assemble a “virtual collection” of frozen or otherwise suitably preserved tissues or DNA samples representing on the order of 10,000 extant vertebrate species as well as some recently extinct species that are amenable to genomic sequencing (Table 1). This collection represents combined specimen materials from at least 43 participating institutions (Table 2). In most cases, we collected both male and female samples, and for certain species, several samples reflecting geographic diversity and/or diversity within localized populations. Tissues in genetic resources collections have been stored by different methods, which yield varying results with regard to DNA quality [18]. Many tissues that are sampled from the field may be left at ambient temperatures for several hours before they are finally frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored there or at -80°C. Nonetheless, many of these tissues still yield high quality DNA [19]. In other cases, non-cryogenic field buffers [20] are used, although with varying results. In addition to DNA quality, permit and species validation are also important issues (Appendix 1). We follow four general guidelines for Genome 10K sample collection. We seek 10μg of genomic DNA or about 0.5g of frozen tissue for each target species. Tissues may be field preserved in liquid nitrogen, ethanol, or DMSO. Initial preservation in liquid nitrogen is strongly recommended for new acquisitions when field conditions permit. Transport in liquid nitrogen or dry ice is encouraged. Tissues should be stored in -80ºC freezers or in liquid nitrogen. Tissues should be documented with voucher specimens when feasible. Preserved carcasses are preferred; photo vouchers acceptable and DNA Barcode Page 7 information will be collected for all (DNA barcode reference). In the case of rare or endangered species, a tissue sample, locality, ID by competent biologist and DNA Barcode confirmation or listing in the International Species Information System is nominally acceptable. All specimens used in the G10K project will be obtained and transported in accord with local and international statutes regulating the collection, use, and transport of biological specimens. In addition to samples for DNA extraction, we included 1,006 cryopreserved fibroblast cell lines derived from 602 different vertebrate species, primarily mammals, but include representatives of 300 taxa comprising 42 families of non-mammalian amniotes and one amphibian species, which provides an additional window into the unique cell biology of these species. With the recent development of transformation techniques to create induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from fibroblast lines [21, 22] [23] [24], the potential of cell line studies is greatly expanded. While it is still unclear how well current cell line generation methods can be extended to all vertebrate clades [25] [26], we propose to initiate primary fibroblast cell cultures for as many species as possible, with a target of at least 2,000 diverse species, as corollary to the Genome 10K project. These cell cultures, along with cDNA derived from primary tissues, will provide direct access to gene expression and regulation in the vertebrate species we catalog and provide a renewable experimental resource to complement the Genome 10K genome sequences. For at least one species of each vertebrate Order, we propose to assemble additional genomic resources, including physical maps and a BAC library, cell lines, and primary tissues for transcriptome analysis. For these species, we will also sequence multiple individuals to assess within-species diversity, including members of Page 8 both sexes to assess sex chromosome differences. A resource of this magnitude would help catalyze a much-needed extension of experimental molecular biology beyond the very limited set of model organisms it currently explores. The Genome 10K species collection will include tissue/DNA specimens from five major taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, amphibians, non-avian reptiles and fishes (Table 1). Mammals Mammals contain a morphologically and behaviorally diverse assemblage of approximately 5,400 species distributed in three major lineages: monotremes (platypus and echidnas—5 species), marsupials (~330 species, including the koala, kangaroos, opossums, etc.), and the speciose eutherian, or placental mammals (~5,000 species). The Genome 10K collections contain exemplars of all 139 families and we have access to ~90% of non-muroid and non-sciurid rodent genera and non-vespertilionid bat genera (Appendix 2, mammals). Ultimately, we will target all 1,200–1,300 genera. Additional sampling will be applied to deeply divergent, and especially endangered, or EDGE (Evolutionary Distinct and Endangered) species, including all species of Zaglossus (echidna), Cuban and Hispaniolan Solenodon, saddle-baked tapir, aardvark, and others. For fundamental biological investigation, it is a high priority to sequence “extremophiles”, such as deep sea divers, high elevation species, aquatic versus terrestrial taxa, species spanning the range of brain size, body size, and morphological convergence as well as aquatic species, gliders, lifespan extremes, nocturnal/diurnals, species with distinct sensory modalities, such as echolocation, and social versus solitary species with diverse mating systems and varying levels of paternal care and care from the social group. Page 9 Capturing wide ecological diversity holds great potential in identifying the genomic changes underlying the major mammalian anatomical and behavioral transformations including the dramatic changes underlying the evolution of advanced social and eusocial systems. We project approximately 3,000 of the 5,400 living mammal species. Birds Like eutherian mammals, modern birds (Neornithes) arose in the Late Cretaceous and diversified soon after the KT extinction event, 65 Ma. Since then, birds have dispersed across the globe and now occupy most of Earth's habitats and diverse ecosystems representing a wide array of functional lifestyles. At this time, we know very little about the genetic and developmental underpinnings of this biological diversity, but we expect that many key questions can and will be addressed as whole genome sequences are accumulated and interpreted. During recent decades, the avian systematic community built large frozen tissue collections that house high quality samples of a substantial portion of avian diversity. These collections provide an essential resource for future genomic analyses of avian structural, functional, and behavioral diversity. With representation from 15 natural history collections distributed globally, the Genome 10K collection includes specimens from 100% of the 27 orders, 87% of the 205 families, 71% of the 2,172 genera and 50% of the 9,723 species of birds (Appendix 2, birds). Every order is represented in multiple collections, as are all but 5 families and all but 104 genera, which is important for ensuring at least one sample of high quality. We plan to sequence both sexes for many lineages, especially the ratite birds, many of which have apparently monomorphic or near-monomorphic sex chromosomes. Sampling each genus may result in Page 10 oversampling of some avian orders and families (such as the extremely diverse passerines or hummingbirds), but we will strive to capture maximal phylogenetic coverage across all bird species. Non-avian Reptiles Non-avian reptile diversity includes snakes, lizards, turtles, crocodilians, and one or two species of tuatara. Because the traditional view of interfamilial relationships (based on morphology) differs appreciably with recent molecular phylogenies and the molecular phylogenies with one another, major issues such as the origin of snakes (which are clearly nested within lizards) remain controversial (NEW REF: Fry et al. 2006). In addition to these uncertainties, the phylogenetic relationships within and among the major groups of reptiles (i.e., families) are often unstable, especially as this relates to “colubroid” snakes and speciose assemblages of lizards. Major revisions occur within many groups, such as the geckos, where additional families are now recognized. Following online databases and Townsend et al. (2004) [27], reptile diversity is distributed among the following groupings: Snakes are divided among 19 families, 477 genera, and 3,048 species. Lizards are comprised of 33 families, 490 genera, and 5,057 species. Turtle diversity is divided among 13 families, 91 genera, and 313 species (NEW REF: Turtle Taxonomy working group, 2007). Crocodiles include 23 species divided among 7 genera in 3 taxonomic families. The tuatara is the only extant member of the formerly diverse and widespread Rhyncocephalia. Total reptile diversity therefore includes 70 families, 1,067 genera, and 8,443 species. The Genome 10K collection has 67%, 34% and 10% of these, respectively (Appendix 2, reptiles). Page 11 Amphibians The Class Amphibia is divided into three orders: Anura (frogs), Caudata (salamanders) and Gymnophiona (caecilians), derived from a common ancestor 260 Ma and representing the only three surviving lineages from a much greater diversity that existed before the Permian extinction 250 Ma (NEW REF: Marjanović, D. and M. Laurin, Fossils, molecules, divergence times, and the origin of lissamphibians. Systematic Biology, 2007. 56: p. 369-388.). These major clades contain 5,773 frog species, 580 salamander species, and 176 caecilian species, respectively. Amphibian taxonomy is currently in a state of flux, if not disarray, with different groups of systematists making frequent and often conflicting changes. Although controversial, we summarize amphibian diversity and tissue holdings for higher taxonomic groups (Appendix 2, amphibians) following the Amphibian Species of the World data base [41]. This reference largely follows the taxonomy of Frost et al. (2006) [29], but also incorporates subsequent changes. This schema tends to split groups, adding more families and genera, which helps us identify the major lineages using the standard ranks of Linnean classification. This taxonomy contains 61 families of amphibians shared among the three orders, containing a total of 510 genera and 6,260 species. The Genome 10K collection contains a total of 394 species (6%), 144 genera (28%), and 45 families (74%) (Appendix 2, amphibians). Amphibians are notorious for their morphological homoplasy due to developmental constraints [citation in COMMENT] as well as spectacular adaptativa convergences in morphology [citation in COMMENT], behavior, and development, e.g., roughly ten independent evolutionary origins of direct development from an ancestral biphasic life history[citation in COMMENT]. Perhaps the most striking example is the Page 12 convergent evolution in toxicity, coloration and parental care between mantellid frogs of Madagascar and dendrobatid frogs in the Neotropics, as well as repeated parallel evolution of these traits within each of these two taxonomic families [2 citations given in COMMENT]. Such homoplasies have wrecked havoc on amphibian taxonomy but offer marvelous opportunities to study the genetic basis of the repeated evolution of complex traits involved in both morphological and behavioral evolution. Collectively, amphibians are of global conservation concern [30], most recently because of pathogenic affects of a chytrid fungus, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis [see comment for new citation]. Habitat loss, pollutants, pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers and climatic changes are further contributing to their current demise. In the face of such diversity crises, sequencing many of species of amphibians has enormous to provide insight into novel antimicrobial compounds, given that many species of frogs harbor a diverse array of such compounds (NEW REF: in comments). The same peptide sequence is rarely recovered from closely related species. Genomic approaches to searching for such antimicrobial diversity using stem cell lines, transcriptomes, and whole genomic sequencing, is clearly warranted. Fishes Fishes include all non-tetrapod vertebrates comprising (i) jawless vertebrates (hagfishes and lampreys, 108 species), (ii) chondrichthyans (sharks, rays, chimeras, 970 species), (iii) actinopterygians (ray-fin fishes, 26,950 species), and (iv) piscine sarcopterygians (coelacanths, lungfishes, 8 species). Total described diversity comprises approximately 28,036 species [31], but actual diversity is probably greater than 50,000 species. A broad outline of the evolution of these most deeply coalescing of the vertebrate clades is provided by Stiassny et al. (2004) [32]. Page 13 In keeping with their very ancient origins, fishes account for nearly 50% of all living species of vertebrates, exhibiting a vast diversity in their morphology, physiology, behavior and ecological adaptations, and providing an exceptional opportunity to study basic vertebrate biology. Fishes are also a commercially important group of vertebrates as a food crop totaling about US $51 billion in trade per year, increasingly driven by the aquaculture industry [33]. Some 16% of all protein consumed is fish protein, and about one billion people depend on fishes as their major source of protein. Because of the great demand, many groups of fishes are over-exploited. Molecular data for commercially important species of fishes, especially those that are currently endangered and those raised by aquaculture, will be valuable in designing strategies for maintaining sustainable stocks and combating disease and other threats. Fish tissues for the Genome 10K project reside in a number of institutions and are usually curated as parts of formal institutional collections. The total number of species represented by tissue samples is not known, but 6,400 species have been DNA-barcoded and collections of new species continue to be added. Fresh material from many commonly available species can be obtained easily from fishing boats and the pet-trade industry for both genome and other molecular projects. The Genome 10K project has in hand suitable samples from 60/62 orders (97%), 382/492 families (78%), 1,270 of about 3,006 genera (42%) and 2,667 of about 11,430 species (23%), (Appendix 2, fish). The largest known animal genome is that of the marbled lungfish, Protopterus aethiopicus, with a haploid size of 133 pg (about 130Gb), followed by the salamanders Necturus lewisi and Necturus punctatus at 120pg (about 117Gb) [10]. The genomes are Page 14 bloated through the activity of transposons which, combined with their enormous size, make genome sequencing and assembly extremely challenging. While RNAsequencing is one avenue by which we may get direct access to interesting biology in these species, we recommend that full genome sequencing projects for selected largegenome species be undertaken nonetheless. There are important questions pertaining to gene regulation, genome structure and genome evolution that cannot be answered from analysis of transcribed RNA alone. Discussion Careful observations of the morphological and functional adaptations in vertebrates have formed the basis of biological studies for a millennium, but it is only very recently that we are able to observe the action of evolution directly at the genetic level. It is not known whether convergent adaptations in independent lineages are often governed by analogous changes in a small number of orthologous genome loci or if macro-evolutionary events in separate lineages usually result from entirely idiosyncratic combinations of mutations. Evidence from several recent studies point toward the former hypothesis (still need to get the best cites). For example, adaptive hind limb reduction occurred independently many times in different lineages and even within the same species, just as sticklebacks in different lakes adapted from an ocean to a freshwater environment [34]. These stickleback adaptations are all traced to independent deletions of the same distal enhancer of the PITX2 development gene, demonstrating remarkable convergent evolution at the genomic level [35]. By cataloging the footprints of adaptive evolution in every genomic locus on every vertebrate lineage, the Genome 10K project will provide the power to thoroughly test the “same adaptation, Page 15 same loci” hypothesis, along with other fundamental questions about molecular adaptive mechanisms. In the course of this investigation, we will discover the genetic loci governing fundamental vertebrate processes. The study of the evolution of viviparity is an outstanding example. Birds, crocodiles and turtles all lay eggs, while apart from monotremes, mammals are all live-bearers. Thus, we found one fundamental transition from oviparity to viviparity in these amniotes, which caused a fundamental reorganization in the developmental program and large-scale change in gene interactions that we are only just beginning to understand. Remarkably however, non-avian reptiles have an estimated 108 independent evolution origins of viviparity. Fish have an equally spectacular variety of such transitions, along with some amphibians, such as the frog genus Gastrotheca, which includes species with placental-like structures. These many independent instances of the evolution of viviparity afford an extraordinary opportunity to explore the genomics behind this reproductive strategy. The architecture of sex determination in vertebrates is similarly diverse, with examples of XY, ZW and temperature dependent mechanisms. This provides an equally exciting opportunity. In fact, a few vertebrate species have abandoned sex altogether. What happens when an asexual genome descends from an ancestral sexual genome, as has occurred repeatedly in Aspidoscelis lizard lineages? Are the independent parthenogenetic genomes parallel in any way? In one group of lizards, genus Darevskia, the formation of unisexual species is phylogenetically constrained, yet in others, e.g., Aspidoscelis, it is not. Many species of lizards and snakes are also known to have facultative parthenogenesis: unmated females produce viable eggs and Page 16 offspring. Unisexuality also occurs in amphibians and fishes by gynogenesis, hybridogenesis, and in amphibians by kleptogenesis [citation in COMMENT]. Sequential hermaphrodite fishes can change their sex. Do these parallel convergent changes involve the same genes? By identifying the genomic loci that support different evolutionary innovations, such analyses will drive fundamental progress in molecular and developmental biology, as have discoveries of the molecular basis for human diseases. The diversity of vertebrate species that cohabit on our planet attests to underlying life processes with remarkable potential. Genomics reveals a unity behind these life processes that is unrivaled by any other avenue of investigation, exposing an undeniable molecular relatedness and common origin among species. By revealing genetic vulnerabilities in endangered species and tracking host-pathogen interactions and coevolution, genomics plays an increasing role in sustaining biodiversity and tracking emerging infectious diseases. Access to the information contained in the genomes of threatened and endangered species is an important component of the Genome 10K project and provides crucial information for comparative vertebrate genomics, while generating information that may assist conservation efforts [36] [37]. In studying the genomes of recently extinct species as well, molecular aspects of species vulnerability are revealed and vital gaps in the vertebrate record restored. In all these ways, the Genome 10K project will engage the public in the quest for the scientific basis of animal diversity and in the application of the knowledge we gain to improve animal health and species conservation. As Guttenberg altered the course of human history with the publication of the first book, so did the human genome project forever change the course of the life sciences Page 17 with the publication of the first full vertebrate genome sequence. When Guttenberg’s success was followed by the publication of other books, libraries naturally emerged to hold the fruits of this new technology for the benefit of all who sought to imbibe the vast knowledge made available by the new print medium. We must now follow the human genome project with a library of vertebrate genomes, a genomic ark for thriving and threatened species alike, and a permanent digital recording of countless molecular triumphs and stumbles across some 500 million years of evolutionary episodes that forged the “endless forms most beautiful” that make up our living world. Methods: Branch length estimates: Page 18 Appendix 1: Policy issues The Genome 10K consortium members recognize this endeavor to be a noncommercial research program without “reach-through” intellectual property (IP) agreements. All individual(s)/institute(s) contributing biomaterials for sequencing thus comply with the above mentioned noncommercial policy and acknowledge that contributed samples have been collected and distributed in accordance with applicable national and international laws and regulations. The reference materials used for genome sequencing should be clearly identified, accessible and where possible, adhere to best practices for biodiversity repositories (particularly concerning taxonomic identification of voucher specimens/tissues and genome size estimation [38]). Reference documentation should include digital images/CT scans of the morphological voucher specimens, geospatial coordinates of the specimen collection site [39] and other emerging metadata standards proposed for genome sequences [40]. Deposition and publication will follow the Ft Lauderdale agreement in accord with prior best practices in genomic research, including release of primary sequence data to the international databases within 24 hours and release of the full genome assemblies as soon as quality assurance is complete. Consortium is committed to building programs for training of highly qualified personnel, particularly in developing nations. Page 19 Appendix 2: Detailed table of classes, orders, families, genera and species Group Orders Families Genera Species Mammals Afrosoricida 2/2 - 100% 7/19 - 36% 7/51 - 13% Mammals Artiodactyla 10/10 - 100% 81/89 - 91% 156/240 - 65% Mammals Carnivora 15/15 - 100% 82/126 - 65% 131/287 - 45% Mammals Cetacea 11/11 - 100% 38/40 - 95% 80/84 - 95% Mammals Chiroptera 13/18 - 72% 74/203 - 36% 162/1116 - 14% Mammals Cingulata 1/1 - 100% 3/9 - 33% 4/21 - 19% Mammals Dasyuromorphia 2/3 - 66% 3/23 - 13% 3/71 - 4% Mammals Dermoptera 1/1 - 100% 1/2 - 50% 1/2 - 50% Mammals Didelphimorphia 1/1 - 100% 6/17 - 35% 8/87 - 9% Mammals Diprotodontia 11/11 - 100% 19/39 - 48% 27/143 - 18% Mammals Erinaceomorpha 1/1 - 100% 4/10 - 40% 6/24 - 25% Mammals Hyracoidea 1/1 - 100% 3/3 - 100% 4/4 - 100% Mammals Lagomorpha 2/3 - 66% 7/13 - 53% 16/92 - 17% Mammals Macroscelidea 1/1 - 100% 3/4 - 75% 3/15 - 20% Mammals Microbiotheria 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% Mammals Monotremata 2/2 - 100% 2/3 - 66% 2/5 - 40% Mammals Notoryctemorphia 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/2 - 50% Mammals Paucituberculata 1/1 - 100% 3/3 - 100% 3/6 - 50% Mammals Peramelemorphia 2/3 - 66% 3/8 - 37% 3/21 - 14% Mammals Perissodactyla 3/3 - 100% 6/6 - 100% 16/17 - 94% Mammals Pholidota 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 6/8 - 75% Mammals Pilosa 4/4 - 100% 5/5 - 100% 7/10 - 70% Mammals Primates 14/15 - 93% 54/69 - 78% 145/376 - 38% Mammals Proboscidea 1/1 - 100% 2/2 - 100% 3/3 - 100% Mammals Rodentia 29/33 - 87% 118/481 - 24% 274/2277 - 12% Mammals Scandentia 2/2 - 100% 3/5 - 60% 9/20 - 45% Mammals Sirenia 2/2 - 100% 2/3 - 66% 2/5 - 40% Mammals Soricomorpha 3/4 - 75% 19/45 - 42% 26/428 - 6% Mammals Tubulidentata 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% Birds Anseriformes 3/3 - 100% 41/52 - 78% 129/162 - 79% Birds Apodiformes 2/3 - 66% 97/125 - 77% 238/429 - 55% Birds Caprimulgiformes 5/5 - 100% 17/22 - 77% 47/118 - 39% Birds Charadriiformes 14/18 - 77% 66/90 - 73% 208/383 - 54% Page 20 Group Orders Families Genera Species Birds Ciconiiformes 3/3 - 100% 32/39 - 82% 69/116 - 59% Birds Coliiformes 1/1 - 100% 2/2 - 100% 5/6 - 83% Birds Columbiformes 1/2 - 50% 31/44 - 70% 129/311 - 41% Birds Coraciiformes 9/11 - 81% 34/51 - 66% 96/209 - 45% Birds Cuculiformes 1/1 - 100% 22/36 - 61% 53/138 - 38% Birds Falconiformes 3/3 - 100% 60/83 - 72% 145/304 - 47% Birds Galliformes 5/5 - 100% 56/80 - 70% 131/290 - 45% Birds Gaviiformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 3/5 - 60% Birds Gruiformes 9/10 - 90% 32/59 - 54% 73/196 - 37% Birds Musophagiformes 1/1 - 100% 5/6 - 83% 16/23 - 69% Birds Opisthicomiformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% Birds Passeriformes 90/107 - 84% 838/1226 - 68% 2796/5756 - 48% Birds Pelecaniformes 7/7 - 100% 8/9 - 88% 30/62 - 48% Birds Phaethontiformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 3/3 - 100% Birds Phoenicopteriformes 1/1 - 100% 3/3 - 100% 4/5 - 80% Birds Piciformes 5/5 - 100% 53/68 - 77% 255/398 - 64% Birds Podicipediformes 1/1 - 100% 5/6 - 83% 11/22 - 50% Birds Procellariiformes 4/4 - 100% 19/27 - 70% 52/112 - 46% Birds Psittaciformes 1/1 - 100% 67/85 - 78% 186/364 - 51% Birds Sphenisciformes 1/1 - 100% 6/6 - 100% 13/17 - 76% Birds Strigiformes 2/2 - 100% 21/29 - 72% 64/195 - 32% Birds Struthioniformes 6/6 - 100% 14/15 - 93% 37/59 - 62% Birds Trogoniformes 1/1 - 100% 5/6 - 83% 25/39 - 64% Amphibians Anura 32/48 - 66% 107/411 - 26% 302/5532 - 5% Amphibians Caudata 10/10 - 100% 32/66 - 48% 86/552 - 15% Amphibians Gymnophiona 3/3 - 100% 5/33 - 15% 6/176 - 3% Reptiles Testudines 10/14 - 71% 43/98 - 43% 60/295 20% Reptiles Sphenodontia 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/1 100% Reptiles Squamata 35/41 - 85% 309/758 - 40% 735/3996 18% Reptiles Crocodylia 1/1 - 100% 8/9 - 89% 21/25 - 84% Fishes Petromyzontiformes 1/1 - 100% 2/10 - 20% 2/38 - 5% Fishes Myxiniformes 1/1 - 100% 2/6 - 33% 3/24 - 12% Fishes Rajiformes 1/1 - 100% 8/16 - 50% 25/107 - 23% Fishes Torpediniformes 2/4 - 50% 2/5 - 40% 5/15 - 33% Fishes Heterodontiformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 3/5 - 60% Page 21 Group Orders Families Genera Species Fishes Squaliformes 1/1 - 100% 2/2 - 100% 14/19 - 73% Fishes Orectolobiformes 5/5 - 100% 7/8 - 87% 13/17 - 76% Fishes Carcharhiniformes 6/8 - 75% 27/37 - 72% 70/140 - 50% Fishes Echinorhiniformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% Fishes Lamniformes 5/5 - 100% 8/10 - 80% 11/14 - 78% Fishes Hexanchiformes 3/3 - 100% 4/4 - 100% 5/6 - 83% Fishes Chimaeriformes 3/3 - 100% 4/4 - 100% 9/18 - 50% Fishes Lepidosireniformes 2/2 - 100% 2/2 - 100% 2/8 - 25% Fishes Ceratodontiformes 0/1 - 0% 0/1 - 0% 0/1 - 0% Fishes Coelacanthiformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/2 - 50% Fishes Acipenseriformes 2/2 - 100% 3/7 - 42% 5/38 - 13% Fishes Semionotiformes 1/1 - 100% 2/2 - 100% 4/7 - 57% Fishes Amiiformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% Fishes Elopiformes 2/2 - 100% 2/2 - 100% 5/7 - 71% Fishes Anguilliformes 14/15 - 93% 27/70 - 38% 52/159 - 32% Fishes Clupeiformes 4/6 - 66% 20/53 - 37% 38/142 - 26% Fishes Cypriniformes 4/5 - 80% 43/327 - 13% 92/1588 - 5% Fishes Characiformes 10/13 - 76% 44/104 - 42% 78/325 - 24% Fishes Siluriformes 14/37 - 37% 45/282 - 15% 71/929 - 7% Fishes Gymnotiformes 4/7 - 57% 5/21 - 23% 5/45 - 11% Fishes Esociformes 2/2 - 100% 4/4 - 100% 7/11 - 63% Fishes Salmoniformes 4/4 - 100% 17/36 - 47% 27/188 - 14% Fishes Gadiformes 9/11 - 81% 31/52 - 59% 54/132 - 40% Fishes Batrachoidiformes 1/1 - 100% 4/9 - 44% 7/16 - 43% Fishes Lophiiformes 10/12 - 83% 16/24 - 66% 21/45 - 46% Fishes Cyprinodontiformes 8/9 - 88% 29/109 - 26% 87/626 - 13% Fishes Beloniformes 5/5 - 100% 17/31 - 54% 36/97 - 37% Fishes Scorpaeniformes 20/32 - 62% 63/130 - 48% 149/465 - 32% Fishes Perciformes 114/151 - 75% 492/1108 - 44% 1213/4698 - 25% Fishes Pleuronectiformes 11/11 - 100% 64/95 - 67% 91/213 - 42% Fishes Osteoglossiformes 6/6 - 100% 9/28 - 32% 10/142 - 7% Fishes Polypteriformes 0/1 - 0% 0/2 - 0% 0/9 - 0% Fishes Gonorynchiformes 2/4 - 50% 2/7 - 28% 2/10 - 20% Fishes Mugiliformes 1/1 - 100% 5/8 - 62% 6/26 - 23% Fishes Tetraodontiformes 10/10 - 100% 51/69 - 73% 92/181 - 50% Page 22 Group Orders Families Genera Species Fishes Myliobatiformes 6/7 - 85% 18/22 - 81% 57/112 - 50% Fishes Atheriniformes 6/8 - 75% 13/33 - 39% 19/174 - 10% Fishes Synbranchiformes 2/2 - 100% 5/6 - 83% 6/19 - 31% Fishes Beryciformes 7/7 - 100% 12/18 - 66% 30/49 - 61% Fishes Stomiiformes 6/7 - 85% 18/21 - 85% 30/52 - 57% Fishes Albuliformes 1/1 - 100% 1/2 - 50% 2/14 - 14% Fishes Pristiformes 1/1 - 100% 2/2 - 100% 4/5 - 80% Fishes Zeiformes 4/5 - 80% 8/11 - 72% 12/17 - 70% Fishes Gasterosteiformes 7/10 - 70% 21/37 - 56% 31/98 - 31% Fishes Myctophiformes 2/2 - 100% 18/32 - 56% 28/90 - 31% Fishes Aulopiformes 12/14 - 85% 24/32 - 75% 36/68 - 52% Fishes Lampridiformes 6/6 - 100% 8/9 - 88% 10/15 - 66% Fishes Percopsiformes 2/3 - 66% 2/3 - 66% 2/4 - 50% Fishes Polymixiiformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 3/4 - 75% Fishes Stephanoberyciformes 5/7 - 71% 9/17 - 52% 10/49 - 20% Fishes Dactylopteriformes 1/1 - 100% 2/2 - 100% 3/4 - 75% Fishes Ophidiiformes 3/3 - 100% 12/18 - 66% 14/24 - 58% Fishes Argentiniformes 4/6 - 66% 8/21 - 38% 13/32 - 40% Fishes Ateleopodiformes 1/1 - 100% 1/2 - 50% 1/3 - 33% Fishes Notacanthiformes 2/2 - 100% 4/4 - 100% 6/7 - 85% Fishes Rhiniformes 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% 1/1 - 100% Fishes ???? 9/10 - 90% 15/24 - 62% 32/74 - 43% Page 23 Appendix 3: Technological issues (To be provided) Page 24 Authors: Coordinators: David Haussler, Stephen J. O’Brien, Oliver Ryder Mammals Group Members: Scott Baker, James Estes, Jennifer Graves, Alexander Graphodatsky, Kris Helgen, *Warren Johnson, Harris Lewin, Gordon Luikart, *William Murphy, Steve O’Brien, Oliver Ryder, Mark Springer, Emma Teeling, Terrie Williams, Nathan Wolfe, YaPing Zhang Birds Group Members: *Keith Barker, Joel Cracraft, Scott Edwards, Olivier Hanotte, *Fred Sheldon Amphibians and Reptiles Group Members: *Andrew J. Crawford, Matthew LeBreton, Paolo Martelli, *Jim McGuire, *Robert Murphy, Brad Shaffer, *Barry Sinervo Fishes Group Members: Fred Allendorf, Giacomo Bernardi, Guillamo Orti, David Rawson, *Byrappa Venkatesh, Robert Vrijenhoek, Robert Ward, *Ed Wiley General Policy Group Members: Scott Baker, *Adam Felsenfeld, Eric Green, *Robert Hanner, *Olivier Hanotte, David Haussler, Paul Hebert, Steve O'Brien, Oliver Ryder, Hector Seuanez, YaPing Zhang Analysis Group Members: *Michele Clamp, Mark Diekhans, David Haussler, Bailey Kessing, David Kingsley, *Webb Miller, Ngan Nguyen, Brian Pike, Stephan Schuster, Josh Stuart, Steve Turner *Chairs Page 25 References: 1. Collins, F.S., M. Morgan, and A. Patrinos, The human genome project: lessons from large-scale biology. Science, 2003. 300(5617): p. 286-90. 2. Lander, E.S., et al., Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature, 2001. 409(6822): p. 860-921. 3. Venter, J.C., et al., The sequence of the human genome. Science, 2001. 291(5507): p. 1304-51. 4. Sodergren, E., et al., The genome of the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Science, 2006. 314(5801): p. 941-52. 5. Dehal, P., et al., The draft genome of Ciona intestinalis: insights into chordate and vertebrate origins. Science, 2002. 298(5601): p. 2157-67. 6. Holland, L.Z., et al., The Amphioxus genome illuminates vertebrate origins and cephalochordate biology. Genome Res, 2008. 18(7): p. 1100-11. 7. Hillier, L.W., et al., Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution. Nature, 2004. 432(7018): p. 695-716. 8. Aparicio, S., et al., Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science, 2002. 297(5585): p. 1301-10. 9. Osorio, J. and S. Retaux, The lamprey in evolutionary studies. Dev Genes Evol, 2008. 218(5): p. 221-35. 10. Gregory, T. Animal Genome Size Database. 2009 [cited 2009 May 1]; Available from: http://www.genomesize.com. 11. Shimeld, S.M. and P.W. Holland, Vertebrate innovations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000. 97(9): p. 4449-52. 12. Baker, C.V., The evolution and elaboration of vertebrate neural crest cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 2008. 18(6): p. 536-43. 13. Meulemans, D. and M. Bronner-Fraser, Amphioxus and lamprey AP-2 genes: implications for neural crest evolution and migration patterns. Development, 2002. 129(21): p. 4953-62. 14. Waterston, R.H., et al., Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature, 2002. 420(6915): p. 520-62. 15. Siepel, A., et al., Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res., 2005. 15(8): p. 1034-1050. Page 26 16. King, M.C. and A.C. Wilson, Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees. Science, 1975. 188(4184): p. 107-16. 17. Bejerano, G., et al., Ultraconserved elements in the human genome. Science, 2004. 304(5675): p. 1321-5. 18. Edwards, S., S. Birks, and R. Brumfield, Future of avian genetic resources collections: Archives of evolutionary and environmental history. Auk, 2005(122): p. 979-284. 19. Brumfield, R., Pers. Comm. 2009: Louisianna State University. 20. Seutin, G., B. White, and P. Boag, Preservation of avian blood and tissue samples for DNA analysis. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 1991(69): p. 82-90. 21. Okita, K., T. Ichisaka, and S. Yamanaka, Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature, 2007. 448(7151): p. 313-7. 22. Stadtfeld, M., et al., Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science, 2008. 322(5903): p. 945-9. 23. Yu, J., et al., Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science, 2009. 24. Yusa, K., et al., Generation of transgene-free induced pluripotent mouse stem cells by the piggyBac transposon. Nat Methods, 2009. 6(5): p. 363-9. 25. Trounson, A., Rats, cats, and elephants, but still no unicorn: induced pluripotent stem cells from new species. Cell Stem Cell, 2009. 4(1): p. 3-4. 26. Liu, H., et al., Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from adult rhesus monkey fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell, 2008. 3(6): p. 587-90. 27. Townsend, T., et al., Molecular phylogenetics of Squamata: the position of snakes, amphisbaenians, and dibamids, and the root of the squamate tree. Systematic Biology, 2004(53): p. 735-757. 28. Roelants, K., et al., Global patterns of diversification in the history of modern amphibians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007. 104(3): p. 887-92. 29. Frost, D.R., The amphibian tree of life. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, no. 297. 2006, New York, NY: American Museum of Natural History. 370 , [1] folded leaf of plates. 30. Mendelson, J.R., 3rd, et al., Biodiversity. Confronting amphibian declines and extinctions. Science, 2006. 313(5783): p. 48. Page 27 31. Nelson, J.S., Fishes of the world. 4th ed. 2006, Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley. xix, 601 p. 32. Stiassny, M., E. Wiley, and G. Johnson, Gnathostome fishes, in Assembling the Tree of Life, J. Cracraft and M. Donoghue, Editors. 2004, Oxford University Press: New York. p. 410-429. 33. Tidwell, J.H. and G.L. Allan, Fish as food: aquaculture's contribution. Ecological and economic impacts and contributions of fish farming and capture fisheries. EMBO Rep, 2001. 2(11): p. 958-63. 34. Shapiro, M.D., M.A. Bell, and D.M. Kingsley, Parallel genetic origins of pelvic reduction in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2006. 103(37): p. 13753-8. 35. Kingsley, D., pers comm, Genome10K, Editor. 2009: Santa Cruz. 36. Ryder, O.A., et al., DNA banks for endangered animal species. Science, 2000. 288(5464): p. 275-7. 37. Ryder, O.A., Conservation genomics: applying whole genome studies to species conservation efforts. Cytogenet Genome Res, 2005. 108(1-3): p. 6-15. 38. Hanner, R.H. and T.R. Gregory, Genomic diversity research and the role of biorepositories. Cell Preservation Technology, 2007. 5(2): p. 93-103. 39. Field, D., Working together to put molecules on the map. Nature, 2008. 453(7198): p. 978. 40. Field, D., et al., The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nature Biotechnology, 2008. 26(5): p. 541-547. 41. Frost, D.R., Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference., in Version 5.3 (12 February, 2009). 2009, American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA. 42. Wilson, D.E. and D.M. Reeder, Mammal species of the world : a taxonomic and geographic reference. 3rd ed. 2005, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2 v. (xxxv, 2142 p.). 43. Howard, R., A. Moore, and E.C. Dickinson, The Howard and Moore complete checklist of the birds of the world. Rev. and enl. 3rd ed. 2003, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. 1039 p. AmphibiaWeb: Information on amphibian biology and conservation. [web application]. 2009. Berkeley, California: AmphibiaWeb. Available: http://amphibiaweb.org/. (Accessed: Jun 10, 2009). Page 28 Please chairs proof these numbers; they are the meat of the White paper Add column for coalescence date time for each group also chairs?? The time to most recent common ancestor of amphibians (extant Lissamphibia) dates to 260 Ma (REF: Marjanović, D. and M. Laurin, Fossils, molecules, divergence times, and the origin of lissamphibians. Systematic Biology, 2007. 56: p. 369-388. I’ve been sending all our tissue and species lists to the G10K database so I imagine that Mark and Ngan could get these numbers at the click of a button, yes? Table 1: Vertebrate taxa [41] Group Orders Families Genera Species Mammals 29/29 100% 139/153 91% 552/1231 45% 1107/5417 20% Birds 27/27 100% 179/205 87% 1537/2172 71% 4819/9723 50% Amphibians 3/3 100% 45/61 74% 144/510 28% 394/ 6,529 6% Reptiles 4/4 100% 47/69 67% 361/1066 34% 817/8442 10% 60/62 97% 382/515 74% 1270/4494 28% 2667/27977 10% Fishes Extant of the current Genome 10K collection is tabulated as (number of species in collection) / (total number of species) and percentage with similar summaries for genera, families and orders. The total numbers are computed using the NCBI taxonomy (www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), but substituted the Wilson and Reeder [42] tree for the mammals and the Howard and Moore [43] tree for birds. Amphibian taxonomy follows Frost [41] with modifications by Roelants et al. [NEW REF in comments SEE ALSO FIGURE 5, 2007] and total number of species taken from AmphibiaWeb [44]. Page 29 Table 2: List of collections and participating institutions (Fill this in) Institutions Steward(s) Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Web address http://research.amnh.org/ornithology/personnel/jlc.h tm American Museum of Natural History Joel Cracraft Australian National University NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Biodiversity Research Institute, University of Kansas Edward Wiley Burke Museum, University of Washington NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Círculo Herpetológico de Panamá Roberto Ibáñez CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research Robert Ward http://www.cmar.csiro.au/anfc/ CTR for Reproduction of Endangered Species-San Diego Zoo Oliver Ryder http://www.sandiegozoo.org/conservation/about/ad ministrators/oliver_ryder_ph.d/ Departamento de Zoologia, I.B., UNESP, Sao Paulo Célio F. B. Haddad http://ns.rc.unesp.br/ib/zoologia/anuros/index.html Ocean Park Corporation, Hong Kong Paolo Martelli www.oceanpark.com.hk Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Russian Academy, Siberian Branch Alexander Graphodatsky http://www.bionet.nsc.ru/indexEngl.html Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES LIRANS Institute, University of Bedfordshire, UK, David Rawson Louisiana State University Museum of Zoology NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES http://www.nhm.ku.edu/fishes/ http://www.beds.ac.uk/research/lirans/personnel/ra wson_d Page 30 Institutions Steward(s) Web address LSU Museum of Natural Science Fred Sheldon http://appl003.lsu.edu/natsci/lmns.nsf/$Content/Sh eldon?OpenDocument Marine Mammal Institute, Oregon State University Scott Baker http://mmi.oregonstate.edu/ Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN), Madrid David R. Vieites http://www.vieiteslab.com Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo Hussam Zaher http://www.mz.usp.br/ Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard* NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, UC Berkeley NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Museum Victoria, Australia NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES National Cancer Institute Lab of Genomic Diversity Stephen O’Brien Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) Robert Murphy http://labs.eeb.utoronto.ca/murphy/ Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History Roy W. McDiarmid http://vertebrates.si.edu/herps/ Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Eldredge Bermingham http://www.stri.org/ South Australian Museum Steve Donnellan http://www.samuseum.sa.gov.au/page/default.asp? site=1&id=1307 Swedish Museum of Natural History NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES Texas A&M University William Murphy http://gene.tamu.edu/faculty_pages/faculty_Murphy W.php Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago Harold K. Voris http://www.fieldmuseum.org/research_collections/z http://home.ncifcrf.gov/ccr/lgd/ Page 31 Institutions Steward(s) Web address oology/ Universidade Estadual Paulista (Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências), Rio Claro, Brasil Célio F. B. Haddad http://www.rc.unesp.br/ib/zoologia/ UCLA, Institute of the Environment Matthew LeBreton http://www.ioe.ucla.edu/ctr/staff/LeBreton_Matthew .html University College-Dublin NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES University of California, Riverside NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES University of California, Santa Cruz NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES University of Montana NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES University of Nebraska, Lincoln Guillermo Orti University of Nevada, Las Vegas NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES University of Texas at Arlington Jonathan A. Campbell http://biology.uta.edu/herpetology/ Zoological Institute, Technical University of Braunschweig Miguel Vences http://www.mvences.de/ Zoological Museum of Copenhagen, Denmark NEED TABLE OF SAMPLES http://golab.unl.edu/index.html Page 32 Figure legends (need these) (Fill in references) Legend(s) here Page 33 Figure 1: A phylogenetic view of the vertebrate subclass Page 34 Figure 2: The mammalian radiations Page 35 Figure 3: The birds of the world Page 36 Figure 4: The reptiles of today (Two NEW REFS: in comments) Page 37 Figure 5: The amphibians’ phylogeny (NEW REF: Roelants et al. 2007) Page 38