Conducting a Rapid Evidence Assessment – lessons learned

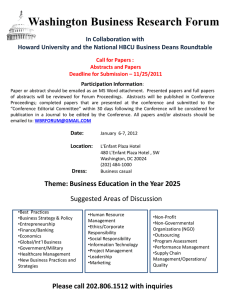

advertisement

Conducting an evidence assessment – method and lessons learned Introduction Last summer the effectiveness of treatment for drug-using offenders within criminal justice settings was highlighted as a key evidence gap. In particular, there was a need to establish which drug treatment interventions for offenders in the CJS are effective, and why, to help inform the roll out of the Criminal Justice Interventions Programme (CJIP). In an attempt to address this evidence gap, the Drugs and Alcohol Research unit in RDS decided to carry out a rapid assessment of existing evidence in this field. This assessment had three main purposes: To provide an addition to the evidence base informing the further development of interventions aimed at drug-using offenders. To inform the planned CJIP evaluations. To identify areas for further research. A paper has been produced setting out the key findings from the assessment as well as implications for policy makers. This was the first time an attempt had been made to conduct a rapid evidence assessment of this type. The original intention was that 3 members of DAR, with assistance from HO library and advice from Cabinet Office colleagues, would be able to complete the exercise within 8 weeks. For future reference, this note sets out the process that was adopted and the time and resource actually devoted to the project. It also presents a number of lessons learned along the way. Method Preparation Having identified the evidence gap in broad terms, three research questions were posed: How effective is treatment (tiers 1 through to 4) for individuals in the criminal justice system in terms of reducing their drug misuse and reducing their drugrelated offending? What evidence is there for the effectiveness of coercive treatment for drug misuse (in terms of reducing drug misuse and drug-related offending) compared to voluntary treatment or no treatment at all? How effective is a case management approach within the Criminal Justice System in terms of criminal justice outcomes? (Case management is defined as the monitoring/supervision and assistance given to an offender from entering through to leaving the criminal justice system by someone working within that system.) As the primary aim of the assessment was to determine the effectiveness of drug treatment, it was agreed that the assessment should only consider evidence from studies conducted using robust quasi-experimental designs. Consequently a systematic review style approach was adopted for the assessment. Time and resource constraints prevented a full systematic review being conducted, so a quasi-systematic approach was adopted. In consultation with Cabinet Office colleagues, a plan was derived to conduct a rapid evidence assessment (REA). Based on the format used in Health Technology Assessments (HTA), rapid evidence assessments are intended to be quasisystematic reviews, carried out in a much shorter timescale to traditional systematic reviews (typically 8-12 weeks compared to 6-12 months)1. The main differences between the REA and a full systematic review were that: a) only published studies were considered (i.e. no ‘grey’ literature was considered), and b) no hand searching of journals took place to ensure that all possible studies had been included. Protected time Before going into detail on the method, it is worth highlighting one consistent theme that ran throughout the project – the need for protected time to be set aside in order to complete the project in the timescales suggested for a rapid evidence assessment. Almost everything took twice as long as originally planned, because initial calculations were based on an assumption that all the time required could be dedicated to the project in one block. In the reality, the assessment had to fit around other work priorities. A two week abstract sift took four weeks; a four week assessment process took eight weeks; and a four week write-up took eight weeks. 1 Cabinet Office (2003) The Magenta Book: Guidance Notes for Policy Evaluation and Analysis The search The following key terms were selected from the research questions: ‘treatment’, ‘offending’, ‘drug’, ‘effectiveness’, ‘coercion’ and ‘criminal justice system’. Alternatives for, and derivatives of, those terms were produced, and were then included in the full list of search terms. This list can be found at Annex A. The search terms were refined and tested in co-operation with Home Office library staff. They advised that that the collection of terms was too extensive and extremely difficult for the databases to cope with. They also advised that it would not be possible, even with the most sophisticated use of Boolean logic, to devise a search strategy that would combine all of them and give sensible results. The final search strings used for each of the databases interrogated are also included at Annex A. HO library staff conducted the search on databases to which the HO library subscribed to at the time2. For each database, two separate searches were conducted. One string was constructed to address the questions on treatment effectiveness and coercion, on the assumption that the way the search terms were constructed, coercive forms of treatment would be captured in the general search for treatment. A separate string was constructed to address the case management question. The following databases were searched. National Criminal Justice Records Service (NCJRS) Criminal Justice Abstracts Medline PsycINFO Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) Social Science Citations Index (SSCI) Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS) There was no direct cost to the project for the CJA and ASSIA searches, as the databases were covered under general HO library subscriptions. All other databases were searched through the Dialog system at a total cost of £1,300. HO library staff spent approximately 30 hours conducting the searches3. To cut down on the time and resource required for the abstract sift and for the assessment itself, a decision was taken to restrict analysis to post-1980 studies from all databases. In total, almost 2,987 abstracts (including duplicates) were elicited from the databases above. The treatment search string produced 2,312 abstracts, while the case management search string produced 675. The majority of abstracts came from NCJRS (1,256 and 405 respectively for the treatment and case management search strings). Since this assessment took place the HO Library has fundamentally revised the way in which literature searches are managed. Desktop access to the abstract databases has been provided to all researchers in RDS to enable them to conduct their own searches. The HO library now undertakes an advisory role in database searching, rather than conducting the searches itself. 3 This Dialog cost is no longer relevant due to the revision mentioned above. All database searches are covered under the desktop access subscriptions managed by the Home Office. Also, HO library staff would no longer carry out the searching. 2 All searching was carried out over a two-week period between 19th August and 11th September 2003. The sift The abstracts were sifted on the basis of a) relevance to the research questions outlined above and b) whether the paper was based on a primary study examining the effectiveness of an intervention. If it was not clear whether the paper was a report of a primary study or was a policy piece, the paper was requested. The sifting process was much more time-consuming than originally envisaged. With almost 3,000 abstracts to sift (and record where appropriate), the three members of DAR originally assigned to the project had difficulty coping with the sheer volume. The sifting process itself took an estimated total of 20 working days. In reality, the sift took much longer than the two calendar weeks originally planned for, as it had to be fitted around other work priorities. It took a month to complete the sift. The first batch of abstracts was sent to DAR on 28th August. The last request for papers was sent on 24th September. Once a paper had been identified, basic bibliographical details were recorded on an excel spreadsheet. This spreadsheet was used to manage the process of requesting papers from the HO library. In most instances the HO library did not hold a copy of the paper requested, but most were easily and quickly obtainable via inter-library loan (ILL) from the British Library. In order to ease the burden on HO library staff, requests were made in batches on a weekly basis. Several lessons for future assessments were learned during the sifting process and are set out below. It has to be acknowledged that some of these issues can be addressed internally, but wider problems with the format and quality of abstracts in particular, can not be rectified solely by the Home Office. Tightening up search criteria With hindsight, the search criteria could have been tightened to exclude a number of spurious abstracts. For example, in this search produced many abstracts for studies into treatment for drink drivers (which were not relevant) and offenders with co-morbidity (which we had chosen to exclude from this assessment as these special conditions require much different types of intervention). Current guidance on conducting systematic reviews suggests that NOT Boolean terms should not be used to avoid the risk of excluding potentially relevant studies. For this project the HO library was advised not to include NOT terms in the search strings. However, a more pragmatic approach adopted for a REA which used NOT terms may have helped reduce the burden of the abstract sift. Duplication of abstracts Abstracts for most studies were found in more than one database. If duplicates had been eliminated a great deal of time and effort would have been saved during the sifting process. (It subsequently came to light that duplicates could be removed in Dialog. As a result of miscommunication between DAR and the HO Library, duplicates for the databases searched using Dialog were included). Both points above highlight the need to ensure a clear understanding about the search strategy is reached before the search starts, if searches are being carried out by a third party (i.e. someone not involved in the assessment itself). "Hard to reach" papers In this assessment we sifted abstracts from the most comprehensive database last. Many of the papers found on NCJRS were often harder to get hold of than traditional journal articles. For example, a significant number of reports on drug court evaluations that had been prepared for the individual jurisdictions operating the drug courts were publicly available but were not published in peer-reviewed journals and/or available via ILL. It is perhaps advisable to start with NCJRS for two reasons. Firstly, it produced by far the greatest number of abstracts (and most studies found on other databases were also found on NCJRS). Secondly, because a higher proportion of the papers found on NCJRS were harder to obtain, the longer the time available to find them the better. Managing the process - systematic recording of studies All studies requested were recorded on an excel spreadsheet, but this became very unwieldy and difficult to manage. A few papers were requested and received twice, suggesting that the process was not foolproof. The HO library has suggested that in-built mechanisms to avoid requesting duplicate papers may have failed because more than one member of the assessment team was making requests for papers and more than member of HO library staff were making ILL requests. A software package such as Endnote or RefWorks to manage the process would have been an extremely useful tool4. Format of abstracts Most abstracts from the library arrived in unwieldy rich text files, which had to printed off and read. It was not easy to transfer the necessary information from the abstracts to the recording spreadsheet (see above) electronically. A more user-friendly format for abstracts would speed up the abstract sift greatly5. Quality of abstracts The primary basis for inclusion in the assessment was methodology. However, the relatively poor quality of many of the abstracts made it difficult to determine whether a study was suitable for inclusion. In many cases, no details were given on methodology. We adopted a cautious approach and consequently requested many papers on studies that were not based on a suitably rigorous methodology. This added considerable time and expense to the subsequent assessment process. Document delivery costs for this project amounted to £1,000. The assessment A total of 238 papers were identified and requested during the sift stage. In the time available (an arbitrary cut-off point of October 30th was set), 198 papers were received. At the time of writing, HO library is in the process of purchasing a RefWorks licence, which will facilitate desktop access to all members of RDS. 5 This was mainly due to the way in which Dialog produced output. Again, now desktop access to the abstract databases has been organised and RefWorks has been purchased, this problem has to a large extent been resolved. 4 The remainder could not be obtained via inter-library loan from the British Library, or the source of the paper could not be identified. As mentioned above, it was not always possible to tell from an abstract whether a paper was a policy piece of whether it was a report of a primary study. Of the 198 papers received, 120 were reports of primary studies. The remaining papers were primarily discursive pieces or literature reviews. (For the literature reviews, it must be noted that in most cases, they had been identified as such by the abstract. These papers were acquired to provide further background information for the assessment and to gauge whether the studies we had found were broadly representative of the literature in this field. They were not requested because poor abstracts failed to identify the nature of the paper, as was the case with most of the discursive pieces.) The 120 primary studies were then reviewed to determine whether they were a) relevant to the research questions and b) methodologically sound. Once a study had been acknowledged as relevant, an initial assessment of the methodology was carried out based on the “Maryland Scale”, devised by Sherman et al (1998) at the University of Maryland for a systematic review into what works in crime prevention. The Scale can be found at Appendix C. Only those studies with a robust comparison group design (point 3 on the “Maryland Scale”) were considered to be sufficiently robust for inclusion in the assessment. Sherman et al argue that only those studies using a robust comparison group can provide strong evidence of causality (and hence effectiveness). A total of 64 relevant studies rating at least 3 on the Scale were identified for further assessment. This further assessment was carried out using an ad hoc “Quality Assessment Tool” (QAT) devised specifically for this project. The QAT was based on a combination of more detailed criteria prepared for the systematic review by the University of Maryland Team mentioned above and criteria established by the Crime and Policing Group in RDS for a recently conducted systematic review of studies on HR management and police performance. By this stage in the process it had become clear that extra resource would be required for the assessment stage in order to speed up the process. In total 7 members of DAR undertook the assessments. To develop and refine the QAT, the 6 original reviewers (a 7th reviewer joined at a later date) each reviewed the same 3 studies. The individual assessments were then compared and a consensus was reached over any discrepancies between scores. This process had the dual effect of refining the QAT guidance and ensuring that there was an element of consistency between the reviewers when assessing the papers. Each study was marked according to its methodology in four key areas: sample selection; bias; data collection and data analysis. Each element was rated as either 1 (good), 2 (average), 3 (weak) or 5 (unable to determine from the paper). The scores for each component were than added together to provide and overall rating for the study. Those studies with the lowest scores were considered the most methodologically robust. The minimum score available was 4, with a maximum score of 20. A potential flaw in this scoring system was the use of a ‘5’ score when a particular criterion could not be marked due to a lack of evidence within a paper. This potentially resulted in a number of sound studies being excluded based on the result of scant or poor reporting of methodology, rather than a poor methodology per se. However, in defence of this approach, studies that were inadequately reported had to be excluded on the basis that the reviewers could not be sufficiently confident in the methodology based on the available evidence. If time were available, those studies where it was felt that scant reporting resulted in exclusion might have been followed up. However, this was simply not feasible for this evidence assessment. Two reviewers assessed each study. Where “major” discrepancies between the QAT scores existed (greater than 2 points), the study was assessed independently by a third reviewer. Where the third reviewer agreed with one of the original scores that score was chosen. If the third reviewer produced a different score to both of the original scores, the third reviewer took the final decision on the score. It has been suggested that this is a rather arbitrary process. It was rightly pointed out that there is no real justification for the third reviewer’s judgement to supersede the previous judgements. However this approach was necessitated by the timescale. If time were available, a more systematic approach would have been adopted whereby the two original reviewers came to a consensus on the score. In total, there was a “major” discrepancy between the scores in 14 of the 64 studies assessed. This suggests that the QAT may have benefited from further guidance to ensure greater consistency between reviewers. Once a final score had been established for each study, they were rated as either strong, average, weak (but eligible for consideration) and poor (and not eligible for consideration). Those studies with a score of 4 to 6 were considered strong (8 studies); studies with a score of 7 or 8 were average (21 studies); while studies with a score of 9 & 10 were considered weak but eligible for consideration (21 studies). Studies with a score of greater than 10 were excluded from further consideration as they were considered to be so poor methodologically that the results could not be relied upon (14 in total). Further details on the criteria used in the QAT can be found in Annex B, along with the guidance notes prepared for reviewers. As with the sifting stage, several lessons for the future were learned during the assessment stage. “Singing from the same songsheet” If an evidence assessment is to be undertaken by a team (and resource constraints are likely to dictate that it is a team exercise), it is essential that all the reviewers in the team interpret the scoring guidelines in the same manner. Developing the QAT completion guidelines was a much more difficult process than originally envisaged. The refinement exercise proved to be invaluable in terms of ensuring that people were interpreting the criteria in the same manner. However, once the assessment stage was underway, it became clear that interpretations still varied across the reviewers. This makes the ‘systematic’ approach very difficult to manage. Almost one in four of the studies assessed produced significantly different scores between the two reviewers assigned the studies. Arbitration by a third reviewer was required in these instances, but there remains a question mark as to how systematic the arbitration process was, given that it relied on one further reviewer. Managing the process - systematic recording of assessments All assessments were recorded and aggregated on an excel spreadsheet. As with the abstract sifting spreadsheet, this became very unwieldy and difficult to manage. A great deal of effort had to be put in to keeping track of who had reviewed which paper, which papers were due for a second review, etc, etc. Again, a software package such as Endnote to manage the process may have been an extremely useful tool. Being realistic about the time and effort required to assess papers As with the sifting process, possibly unrealistic expectations were held at the start of the process about how quickly the papers could be assessed. Rating the methodology of studies can be an extremely laborious process, particularly given the poor quality of reporting in many papers. It is also extremely difficult to do for extended periods – devoting whole days to assessing papers was a draining experience! A better approach would be to intersperse assessments with other work. Assessing papers in small batches is likely to lead to a better quality of assessment overall. However, this clearly has implications for the timescale in which an assessment can be carried out. Methodological knowledge It is important that those reviewing papers for an evidence assessment have sufficient knowledge and experience in research methods to carry out the assessment. Some of the discrepancies in QAT scores may not have been the result of different interpretations of the criteria, but a misunderstanding of the methodology as set out in the papers. In turn, this may in part be due to poor reporting, but in some instances a greater knowledge of quasi-experimental research methods may have improved the accuracy and consistency of the assessment. Training on ‘what makes a good study’ would be extremely helpful. Annex A – Search terms Search terms derived Effective: effective*, useful*, practica*, able, work*, outcome, impact, result* Treatment: treat*, screen*, refer*, assess*, harm, specialist, service*, care, community, residential, ‘in*patient’, support, aftercare, throughcare, advice, advize, advis*, ‘social worker*’, teacher*, probation, housing, GP*, nurs*, information, program*, ‘needle exchange’, ‘care plan’, prescrib*, motivation*, ‘drop-in’, outreach, detached, peripatetic, domiciliary, ‘arrest referral’, CARATS, ‘brief interventions’, intervention*, psychotherap*, ‘cognitive behavio*r*’, counselling, methadone, detox*, rehabilitat*, ‘drug testing’, ‘DTTO’, ‘drug treatment and testing order’, ‘stabili*’, abstinence, therap*, help, ‘self-help’, ‘health promotion’ Criminal Justice System: crim*, justice, law, enforce*, correction*, court, arrest, apprehension, prosecution, defense, defence, sentenc*, prison, jail, incarceration, probation, judic*, criminal, offence, offense, custody, bail, trial, pre-trial, parole. Drugs: drug*, substance*, misuse, abuse, illegal, illicit, narcotic, opiates, opioid, tranquillisers, hallucinogen, addict*, heroin, cocaine, crack, methadone, amphetamine*, cannabis, ecstasy, diazepam, temazepam, inject*, overdos*, stimulant* Offending: offense, offence, offend*, crim*, shoplift*, burglar*, robbery, theft, supply, handling, deception, violen* Coercion: coerc*, compel*, involuntary, compulsory, mandatory, obligatory, forc*, necessary Actual search strings used ASSIA Case mgmt: Query: KW=((offender* or burglar*) OR (criminal* or reoffend*) OR (theft or shoplift*)) AND KW=((drug* or narcotic*) OR (substance or heroin) OR (crack or methadone)) AND KW=((case management or case worker) OR (throughcare or through care or aftercare) OR (link worker or care coordinator)) Treatment: Query: KW=((offender* or burglar*) OR (criminal* or reoffend*) OR (theft or shoplift*)) AND KW=((drug* or narcotic*) OR (substance or heroin) OR (crack or methadone)) AND KW=((treatment or therapy) OR (drop in or rehabilitat*) OR (needle exchange)) CJA Case mgmt: (offender* or criminal* or burglar* or theft or shoplift*) and (drug* or narcotic* or heroin or methadone or crack) and (case management or case worker or throughcare or through care or after care or link worker) Treatment: (offender* or criminal* or burglar* or theft or shoplift*) and ((drug* or narcotic* or heroin or crack or methadone) and (illicit or banned or illegal or abuse)) and (treatment or therapy or needle exchange or rehabilitat*) MEDLINE (offender or offenders or criminal or theft or shoplifting or burglar or burglars) AND (drug or drugs or heroin or substance or crack or methadone or narcotic) AND (illicit or illegal or abuse or banned) AND (treatment or therapy or drop in or rehabilitation or needle exchange or CARATS or DTTO) AND (effective or success or relapse) Dialog (for NCJRS, PsycINFO, SSCI and PAIS) Case mgmt: (offender? OR burglar? OR criminal? OR reoffend? OR theft OR shoplift?) AND (drug? OR narcotic? OR abuse OR substance OR heroin OR crack OR methadone) AND (case(w)management OR throughcare OR through(w)care OR case(w)worker OR link(w)worker OR care(w)coordinator OR aftercare) Treatment: (offender? OR burglar? OR criminal? OR reoffend? OR theft OR shoplift?) AND (drug? OR narcotic? OR abuse OR substance OR heroin OR crack OR methadone) AND (treatment OR therapy OR drop(w)in OR rehabilitat? OR needle(w)exchange) AND (illegal OR illicit OR abuse OR banned) AND (effective? OR success? OR relaps?) Breakdown of abstracts produced Database NCJRS CJA ASSIA PAIS SSCI PsycINFO MEDLINE Total Treatment Case mgmt search string search string 1256 405 183 42 293 17 5 13 183 62 204 89 188 47 2312 675 Total 1661 225 310 18 245 293 235 2987 Annex B – Assessment guidance 1) An initial test of the methodology is carried out by ranking it on the Maryland Scale of Scientific Methods. To be included in the assessment the methodology must achieve at least 3 on the Maryland Scale. This is a “comparison between two or more comparable units of analysis, one with and one without the programme”. 2) If the study qualifies for inclusion according to its Maryland Scale ranking, then a more detailed assessment of its methodology will be conducted using a customized quality assessment tool (QAT). The quality criteria on which the methodology for each study should be assessed are set out in the table below, along with detailed guidance notes on how to rate the studies against each criterion. There are four components in the QAT. The first three components (sample, bias and data collection) are assessed on three separate criteria. The fourth component (data analysis) is assessed on a single criterion. For each criterion a score of 1 to 3 will be assigned based on the methodology used. A score of 5 should be recorded where there is insufficient detail to assess the study against that particular criterion. Where a particular criterion is not applicable, a score of 1 should be assigned, but it should be noted that this score was only given because the criterion was inapplicable. The scores for individual criteria will then be averaged to provide an overall score for each component of the QAT (with the exception of the data analysis component). In turn, the scores for each component will be aggregated to provide an overall score for each study. The Maryland Scale of Scientific Methods Level 1: Correlation between a crime prevention programme and a measure of crime or crime risk factors at a point in time. For example, a single, post-treatment survey of clients who have received treatment to compare treatment outcomes with criminal justice outcomes. Level 2: Temporal sequence between the programme and the crime or risk outcome clearly observed, or the presence of a comparison group without demonstrated comparability to the treatment group. For the purpose of this exercise, all comparison group studies should be given a rating of at least 3, with the exception of: a) those studies where the only comparison is between completers and non- (or partial) completers of a particular treatment b) those studies where the comparibility of the comparison groups is seriously compromised and no attempt has been made to control for this (please state reasons). Level 3: A comparison between two or more comparable units of analysis, one with and one without the programme. Level 4: A comparison between multiple units with and without the programme, or using comparison groups that evidence only minor differences. For studies using just one treatment and one non-treatment comparison groups, if those groups evidence major differences prior to the intervention that have to be controlled for statistically, the study should be treated as level 3. (For example, where the dependent variable was recidivism, any significant differences in the level of pre-intervention offending behaviour between comparison groups would need to be controlled for). Only if it has been clearly demonstrated that, prior to the intervention, there is very little difference between comparison groups, then the study should be rated as level 4. Level 5: Random assignment and analysis of comparable units to programme and comparison groups. Differences between groups are not greater than expected by chance. Units for random assignment match units for analysis. Sometimes random assignment takes place at a different level than the analysis, e.g. prisons are randomly assigned, but prisoners are the unit of analysis. These cases should not be treated as random assignments. Further details on the Maryland Scale can be found in: Sherman, LW et al (1998) Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising, Washington, NIJ (http://www.preventingcrime.org/report/index.htm) Quality Assessment Tool Quality indicator 1. Sample a) size b) method c) selection 2. Bias a) response /refusal bias Level of quality Grade Whole population or 100+ participants in both treatment and control groups 70% of population or 50-100 participants in both treatment and control groups Less than 50 participants in both treatment and control groups Not reported Whole population or random samples Purposive samples with potential impact adequately controlled for statistically Purposive samples with potential impact not adequately controlled for statistically, or not controlled for at all Not reported Control and experimental groups comparable Control and experimental groups not comparable, but differences adequately controlled for statistically Control and experimental groups not comparable, and differences not adequately controlled for statistically, or not controlled for at all Not reported No bias Some bias but adequately controlled for statistically Some bias and not adequately controlled for statistically, or not controlled for at all Not reported b) attrition No/very little (< 10%) attrition bias Some attrition butt adequately controlled for statistically Some attrition and not adequately controlled for statistically, or not controlled for at all Not reported c) Control and exp. groups treated equally performance Control and exp. groups not treated equally – minor effect bias Control and exp. groups not treated equally – major effect Not reported 3. Data collection a) method Very appropriate Appropriate Not appropriate Not reported b) timing Very appropriate Appropriate Not appropriate Not reported c) validation Very appropriate Appropriate Not appropriate Not reported 4. Data analysis a) Very appropriate appropriate Appropriate techniques/ Not appropriate reporting Not reported 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 1 2 3 5 Guidance notes for completion of Quality Assessment Tool The overriding guide for the Quality Assessment – assume the worst! If insufficient information is available to assess a particular criterion, mark that as 5. The first two criteria are relatively straightforward and self-explanatory. Further definitions are below: 1c) Sample selection Were the experimental and control groups somehow selected differently, or were not comparable for some reason? For example, did the groups demonstrate very different patterns of offending prior to entering treatment and control groups? This score relates to the ‘recruitment’ phase only, i.e. before any treatment takes place or is even offered. 2a) Response/refusal bias This score relates to any bias that may have been introduced once the samples had been selected. Two examples of potential response/refusal bias: If a study relied on voluntary take-up of treatment/intervention once the treatment sample had been selected, were those that volunteered to participate comparable to all those chosen to participate in the treatment group? See Harrell & Roman (2001) for an example. If a study relied on self-reported data among treatment and control groups (once those groups had been selected), were those in the treatment and control groups who completed the self-report questionnaire/interview comparable to the total populations of the treatment and control groups? 2b) Attrition bias Were all the participants in the experimental and the control samples accounted for? Were there differences between the study participants (in both treatment and control groups) at the pre- and post-test stages? Were there more “lost-to-follow-ups” in one treatment group compared to the control group (or vice versa)? Is attrition evident but no adequate discussion found in the study, or is it discussed but not controlled for adequately? 2c) Performance bias Were experimental and controls dealt with separately other than the intervention under inquiry? Could any other differences in the way in which the groups were treated have any major impact on the outcomes? For example, performance bias will exist where different drug testing regimes were in place for control and treatment groups, if the testing regime itself was not the intervention being investigated. Also, if appropriate, were the participants and interviewers blinded? 3a) Method of data collection What data collection methods were employed, e.g. self-completion questionnaire, structured interview, analysis of administrative data (crime records)? Were these appropriate in terms of supplying the required data to be able to answer the research question(s) posed? Studies that rely on the retrospective collection of self-reported pre- and postintervention data only should be given a maximum score of 2 (given likely recall issues). Studies relying on a single data collection method should be given a maximum score of 2. 3b) Timing of data collection Was the timing of data collection from the control and comparison groups before and after the treatment appropriate? Was a sufficient length of time left after treatment when collecting recidivism data to adequately determine outcome in terms of reduced offending? 24+ month follow-ups should be rated as 1, 12-24 month follow-ups should be rated as 2 and under-12 month follow-ups should be rated as 3. Those studies where no baseline data are collected should be marked as 3 For longitudinal studies, were the data collected at appropriate intervals? rationale given for the timing of the data collection, and was it appropriate? Was a 3c) Validation of data If appropriate, were different sources of data used? Was any triangulation carried out? For example, was self-reported criminality matched to official records? Studies relying on a single data source should be given a maximum score of 2. Studies that rely on a single measure of recidivism should be given a maximum score of 2. Data collection – general Where multiple methods are used, the reviewer must make a judgment regarding the overall standard of the data collection, concentrating on those data deemed most appropriate to answering the research questions. 4a) Appropriate statistics and techniques used Were appropriate statistics used (e.g. Chi-square, t-test, ANOVA, regression) and reported? Were standard deviations reported as well as differences of means? Were lower and upper quartiles reported (or the range) as well as medians? Were confidence intervals reported as well as odds ratio? Were significance levels reported? Were repeated measures reported, i.e. were baseline data and post-treatment data reported? If post treatment data only are reported, the maximum score given should be 2. Annex C – Project resources Planned and actual timetables for the assessment Date Week 11Aug 1 18Aug 2 25Aug 3 01Sep 4 08Sep 5 15Sep 6 22Sep 7 29Sep 8 06Oct 9 13Oct 10 20Oct 11 27Oct 12 03Nov 13 10Nov 14 17Nov 15 24Nov 16 01Dec 17 08Dec 18 15Dec 19 22- 29- 05Dec Dec Jan 20 21 22 12Jan 23 19Jan 24 26Jan 25 Planned timetable Devise strategy Database searches Abstract sifting Papers received Develop assessment tool Assessment Report write up Actual timetable (grey blocks represent the over-run on the planned time allocated to that element of the project) Devise strategy Database searches H Abstract sifting X O Papers received M L Develop assessment tool A I Refine assessment tool S D Assessment A Report write up Y Estimated time spent on the project and total costs Activity Devise strategy Database searches Abstract sifting Requesting papers Develop/refine assessment tool Assessment Report write up Total No of people 6 (3xDAR, 1xCab Off, 2xHO Lib) 1 (1xHO Lib) 3 (3xDAR) 2 (2xHO lib) 6 (6xDAR) 7 (7xDAR) 2 (2xDAR) 7xDAR, 4xHO Lib, 1xCab Off Total hours 20 30 hours searching + 12 hours other admin = 42 hours 20 days x 7.5 hours = 150 hours 36 20 10 per day x 200 reviews = 20 days x 7.5 hours = 150 hours 10 days x 7.5 hours = 75 hours 493 hours Cost (excl staff costs) £1,300 £1,000 £2,300