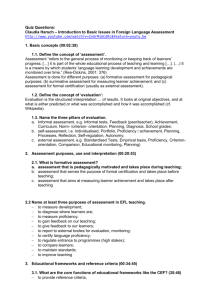

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages

advertisement