PROVISIONAL COURSE OUTLINE ONLY

advertisement

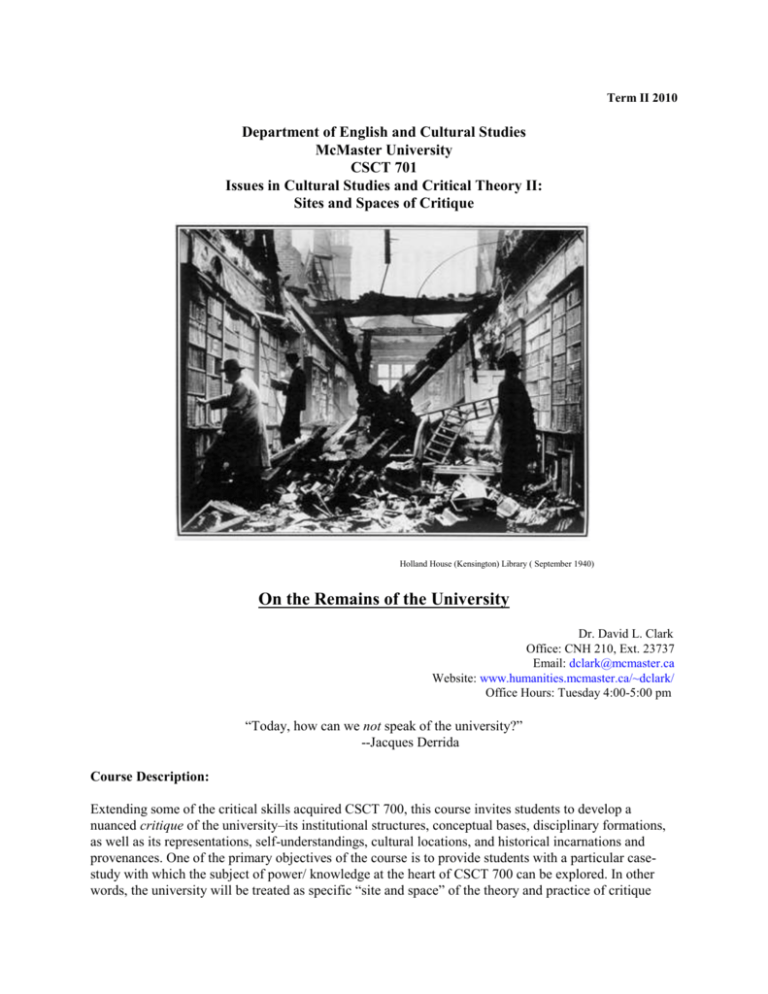

Term II 2010 Department of English and Cultural Studies McMaster University CSCT 701 Issues in Cultural Studies and Critical Theory II: Sites and Spaces of Critique Holland House (Kensington) Library ( September 1940) On the Remains of the University Dr. David L. Clark Office: CNH 210, Ext. 23737 Email: dclark@mcmaster.ca Website: www.humanities.mcmaster.ca/~dclark/ Office Hours: Tuesday 4:00-5:00 pm “Today, how can we not speak of the university?” --Jacques Derrida Course Description: Extending some of the critical skills acquired CSCT 700, this course invites students to develop a nuanced critique of the university–its institutional structures, conceptual bases, disciplinary formations, as well as its representations, self-understandings, cultural locations, and historical incarnations and provenances. One of the primary objectives of the course is to provide students with a particular casestudy with which the subject of power/ knowledge at the heart of CSCT 700 can be explored. In other words, the university will be treated as specific “site and space” of the theory and practice of critique 2 evoked in the program’s other core course. Yet the university is not one object of analyses among many, but rather a question that has direct, pertinent, and problematical relevance to the life and thought of both the students and professors involved in the MA in Critical Theory and Cultural Studies. In theory, so to speak, the university constitutes a space of autonomous critical inquiry, an archive of received knowledges, and the site of the production of new knowledge. This course interrogates that historically sanctioned notion of the university, and instead treats the academy as a cultural phenomenon that calls for sustained, rigorous investigation. A wide range of analyses will be brought to bear on the university, from a historical exploration of the institution’s origins in the German Enlightenment, to its role in the invention and legitimation of bodies of knowledge, especially “the human sciences,” to its complex relationship with technology, global capital, and state power, as well as radical democracy and social justice. A discussion of what the university is and was forms the basis of a critical conversation about its possible futures--or what Jacques Derrida has called “the university to come.” Special emphasis will be given to what Bill Readings describes as “the university in ruins”–the university as the haunted, troubled, and troubling site of remains that critical theory and cultural studies uneasily call home. Working with an array of discourses about the university ranging from Immanuel Kant’s The Conflict of the Faculties (1798) to contemporary critiques of the theory and practice of academic studies, this course will address a number of critical questions, including: What roles do critical theory and cultural studies play in the university today? In what ways is the university an historical effect, an expression of competing social and historical forces that account for its peculiar shape? What is the raison d’etre of the university, past and present? How has the distinction between “applied” and “pure” research constituted and deformed the university? How is the contemporary university caught up in the phenomenon known as “globalization.” What roles do the universities play in the deployment of biopower? Is a university of dissent possible? Required Texts: 1) Readings, Bill. The University in Ruins. Harvard UP, 1996. 2) Giroux, Henry A. and Susan Searls Giroux. Take Back Higher Education: Race, Youth, and The Crisis of Democracy in the Post-Civil Rights Era. New York: Palgrave, 2004. 3) Derrida, Jacques. The Eyes of the University: Right to Philosophy, Vol 2. Stanford UP, 2004. 4) Derrida, Jacques, “University Without Condition.” In Without Alibi. Stanford UP, 2002. [Coursepack] 5) Britzman, Deborah, Lost Objects, Contested Subjects: Toward a Psychoanalytic Inquiry of Learning. Albany: SUNY P, 1998. 6) Giroux, Susan Searls. Between Race and Reason: Violence, Intellectual Responsibility, and the University To Come. Stanford UP, forthcoming. [Coursepack] 7) Simon, Roger I. “The University: A Place to Think?” [To be made available to students as a .pdf] 8) Mark C. Taylor, "End the University as We Know It," http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/27/opinion/27taylor.html 3 9) Henry A. Giroux, "Higher Education Under Siege: Implications for Public Intellectuals," http://www.nea.org/assets/img/PubThoughtAndAction/TAA_06_08.pdf 10) Kate Zerkicke, "Career U: Making College 'Relevant,'" http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/03/education/edlife/03careerism-t.html?scp=1& 11) Tad Friend, "Letter from California: 'Protest Studies: The State is Broke and Berkeley is in Revolt,'" http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/01/04/100104fa_fact_friend [This link only gets you to an abstract of Friend's essay in The New Yorker. To access the entire essay, click "Read the full text of this article in the digital edition. (Subscription required.)" and then use the user name and password I provide in class.) 12) Stanley Fish, "Will the Humanities Save Us?" http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/01/06/will-the-humanities-save-us/ 13) Stanley Fish, "Fish to Profs: Stick to Teaching (Interview with Andy Guess)," http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2008/07/01/fish 14) Stanley Fish, "Neoliberalism and Higher Education," http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/03/08/neoliberalism-and-higher-education/ 15) LaCapra, Dominick, “The University in Ruins?” [Critical Inquiry 25 (Autumn 1998): 33-55] 16) Rey Chow, “‘An Addiction from Which We Can Never Get Free.’” [New Literary History 36.1 (2005) 47-55] (Additional readings will be provided and suggested along the way, depending on the questions, problems, and issues raised in the seminar. Students are especially encouraged to recommend supplemental readings for class discussion.) Work and Mark Distribution, Assignment Descriptions Seminar Participation and Creation (25%) Instead of delivering formal presentations, members of the class will be encouraged and expected to create, on an ongoing basis, a lively graduate seminar–i.e. an inquisitive and informed space of critical labour, discussion, and debate. All students will therefore be expected to contribute consistently and meaningfully to the intellectual life of the seminar, developing and volunteering questions and arguments as well as responding mindfully to queries and challenges that are put to them by their classmates and by their instructor. Students must be willing and able to: –read and engage all assigned materials. –attend all classes and participate in all classes. –explore and absorb as much related critical material as possible, both seeking this material out independently and in consultation with their classmates and instructor. 4 –develop questions and arguments that are directly relevant to the materials at hand, and actively to introduce these points into the class discussion on a consistent basis. –listen and respond thoughtfully to the issues raised in class, engaging the issues in ways that complicate and advance the intellectual life of the seminar. –foster a developing scene of pedagogy, bearing in mind that a central part of our task is to teach others and to be taught. At midterm, students will be given an informal assessment of the quality of their seminar participation work. Authors of response papers circulated in a given class should contribute to the class discussion in an especially robust way, taking particular responsibility for leading the seminar on that day. Response Papers (3 x 10%=30%) Each student will be responsible for three 500-word (2 pages) responses to the readings, each of which is worth 10% of your final grade, for a total of 30%. The papers must be completed and circulated at least 48 hours before the relevant class and circulated to both me and the members of the class via e-mail. (Response papers are assigned by lottery as seen below.) Don’t forget that you need to give your classmates and your instructor time to consider your remarks, and that in any given class, six response papers will be in circulation! Response papers should provide a succinct summary of and engagement with some of the text’s most pressing themes, arguments, and questions. The response paper should be written in such a way to prompt and provoke discussion in class. Authors of the response papers should be prepared to speak in class about the questions and issued raised in those papers. You are free to exchange response paper assignments among yourselves. Response Paper Allotments Student 1: Response papers 3,5,8 Student 2 Response papers 1,4,6 Student 3 Response papers 2,4,6 Student 4 Response papers 2,4,6 Student 5 Response papers 1,3,6 Student 6 Response papers 3,5,7 Student 7 Response papers 1,4,7 Student 8 Response papers 1,5,8 Student 9 Response papers 2,5,7 Student 10 Response papers 2,5,7 Student 11 Response papers 3,6,8 Student 12 Response papers 3,6,8 Student 13 Response papers 2,4,7 Student 14 Response papers 2,5,8 Student 15 Response papers 1,3,8 Student 16 Response papers 1,4,7 Research Essay (45%) 15-20 page essay. Students are encouraged to write a research essay on a topic of their own choosing. Essays will eventually be made available on my website, with the permission of each student. I am happy to discuss your research essay with you at every stage, but all students are expected to consult with 5 me about their work at least once prior to submitting the essay. E-mail protocol: The Faculty of Humanities has issued the following set of instructions to students: “It is the policy of the Faculty of Humanities that all email communication sent from students to instructors (including TAs), and from students to staff, must originate from the student's own McMaster University email account. This policy protects confidentiality and confirms the identity of the student. Instructors will delete emails that do not originate from a McMaster email account.” All e-mails must be written in full sentences (i.e. no point form, no text-messaging short form), and must contain a subject line that includes the course designation, i.e., "701." Receipt of all e-mails from me must be acknowledged. Class cancellations: In the unlikely event of class cancellations, students will be notified on the Department of English and Cultural Studies website and on my website. It is your responsibility to check these sites regularly for any such announcements. Link: http://www.humanities.mcmaster.ca/~english/ (Department of English and Cultural Studies) Link: http://www.humanities.mcmaster.ca/~dclark/ (Dr. David L. Clark) University Statement Regarding Academic Dishonesty: Academic dishonesty consists of misrepresentation by deception or by other fraudulent means and can result in serious consequences, e.g. the grade of zero on an assignment, loss of credit with a notation on the transcript (notation reads: “Grade of F assigned for academic dishonesty”), and/or suspension or expulsion from the university. It is your responsibility to understand what constitutes academic dishonesty. For information on the various kinds of academic dishonesty please refer to the Academic Integrity Policy, specifically Appendix 3, located at: http://www.mcmaster.ca/univsec/policy/AcademicIntegrity.pdf The following illustrates only three forms of academic dishonesty: i) Plagiarism, e.g. the submission of work that is not one’s own or for which other credit has been obtained. ii) Improper collaboration in group work (Insert specific course information) iii) Copying or using unauthorized aids in tests and examinations. All submitted work is subject to normal verification that standards of academic integrity have been upheld. See: http://www.mcmaster.ca/academicintegrity/ Statement from the Office of the Associate Dean, Faculty of Humanities The instructor and university reserve the right to modify elements of the course during the term. The university may change the dates and deadlines for any or all courses in extreme circumstances. If either type of modification becomes necessary, reasonable notice and communication with the students will be 6 given with explanation and the opportunity to comment on changes. It is the responsibility of the student to check their McMaster email and course websites weekly during the term and to note any changes. 7 Provisional Seminar Schedule (Term II 2010) CSCT 701: On the Remains of the University January 12 Prefatory remarks Giroux, “Higher Education Under Siege” Fish, “Stick To Teaching;” “Will the Humanities Save Us?” “Neoliberalism and Higher Education.” Zerkike, “”Career U: Making College ‘Relevant’” Tad Friend, “Protest Studies: The State is Broke and Berkeley is in Revolt” Taylor, “End the University as We Know It.” February 19 Introduction 26 Readings, The University in Ruins (Chapter 1-6) [Response paper 1] 2 Readings, The University in Ruins (Chapter 7-12) 9 LaCapra, Dominick, “The University in Ruins?” [Critical Inquiry 25 (Autumn 1998): 33-55; Rey Chow, “‘An Addiction from Which We Can Never Get Free.’” [New Literary History 36.1 (2005) 47-55] Roger I. Simon, “The University: A Place to Think?” [To be made available to students as a .pdf] March April 16 Reading Week 23 [Class cancelled] 2 Giroux and Giroux, Take Back Higher Education (Chapter 1-3) [Response paper 2] 9 Giroux and Giroux, Take Back Higher Education (Chapter 4-7) [Response paper 3] 16 Derrida, “The Principle of Reason: The University in the Eyes of its Pupils;” “Mochlos,” each from The Eyes of the University [Response paper 4] 23 Derrida, “Vacant Chair: Censorship, Mastery, Magisteriality;” “Sendoffs,” each from The Eyes of the University; “University Without Condition” (Coursepack) [Response paper 5] 30 Giroux, Between Race and Reason [Response paper 6] 6 Giroux, Between Race and Reason [Response paper 7] 13 Britzman, Deborah, Lost Subjects, Contested Objects [Response paper 8]