Relationship Between Intellectual Capital and Knowledge

advertisement

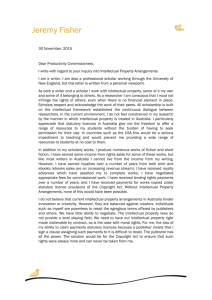

An Empirical Study on the Relationship between Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Creation Yi-Chun Huang, Associate Professor Jih-Jen Liou, Lecturer Dept. of Business Administration National Kaohsiung University of Applied Sciences peterhun@cc.kuas.edu.tw grace@cc.kuas.edu.tw Fax: 886-7-3961245 Tel: 886-7-3814526 ext. 7302 1 Abstract Knowledge creation has become an important topic for knowledge researchers in recent years. However, the existing academic literatures do not provide a clear indication of how new knowledge is created. Few empirical researches are found in this area. This study synthesizes two different literature streams, i.e. intellectual capital and knowledge creation, in order to understand their linkage. It examines and tests the effects of social capital, human capital and structural capital on knowledge creation and the moderating effects on the technological knowledge diversity between intellectual capital and knowledge creation, respectively. The results are found as follows: First, partly proves empirically that intellectual capital is a phenomenon of interactions. Second, partly proves empirically that technological knowledge diversity is a phenomenon of moderations. Finally, all dimensions of intellectual capital are positively and significantly influenced on knowledge creation. Keywords: Knowledge Creation, Intellectual Capital, Technological Knowledge Diversity 2 1. Introduction The knowledge-based view of the firm points out that firms as receivers of knowledge and competencies have received considerable attention in the management and strategy literatures (Kogut and Zander, 1996; Spender, 1996). A large amount of the researches on knowledge examine the organization as the unit of analysis and provide insight view into the importance of knowledge transfer and acquisition between and within organizations (Ahuja, 2000; Hansen, 1999). However, the creation of new knowledge was not received much attention until knowledge researchers have begun to explore a knowledge creation theory (Grant, 1996; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Nonaka, 1994). Furthermore, the existing academic literatures do not provide a clear indication of how new knowledge is created. Few empirical researches are found in this area. According to the viewpoints of knowledge-based researchers, knowledge creation and innovation arises from new combinations of knowledge and other resources (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990; Kogut and Zander, 1992). Previous studies have recently positioned social capital as a key factor in realizing knowledge creation (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; McFadyen and Cannella, Jr., 2004). According to the theory, social capital and knowledge creation will have a positive relationship because social capital directly affects the combine-and-exchange process and provides relatively easy access to network resources (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Wadhwa and Kotha (2006) argued that knowledge creation is from external venturing. Sena and Shani (1999) attempted to propose an alternative framework for intellectual capital and knowledge creation. Nonaka, Toyama & Konno (2000) built a unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. They argued that ba is a place of knowledge creation. Each ba has a physical, a relational, and a spiritual dimension. Ba is here defined as a shared context in motion in which knowledge is created, shared, and utilized (Nonaka, Toyama and Konno, 2000). A key feature of knowledge-based companies is their heavy dependence on intellectual capital (Grandstrand, 1998). Therefore, it is worth to study further for the relationship between intellectual capital and knowledge creation. Despite many different terms and definitions related to the intellectual capital (Brooking, 1996; Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Hussi and Ahonen, 2002; Marr and Schiuma, 2001; Mayo, 2001; Roos et al., 1997; Sveiby, 1997), it seems that there is a common agreement that intellectual capital of an organization consists of three main components: human capital, structural capital and social capital (Lonnqvist, et al., 2005; Seetharaman et al., 2004; Sveiby, 1997). Recently, there is an increasing number of researches focused on the relationship among intellectual capital, innovation and competitiveness. In the papers of McAdam(2002), Darroch and McNaughton(2002), Gleoet and Terziovski(2004), Liu, Chen and Tsai(2005), the interaction between innovation and knowledge management or intellectual capital has been studied. But it is few to explore the relationship between intellectual capital and knowledge creation. Hence, this study will examine the impact of intellectual capital on knowledge creation. 3 Previous studies (Bontis, 1998; Bontis et al., 2000) have revealed that intellectual capital is positively and significantly associated with organizational performance. In this context, the dimensions of intellectual capital are interactive, transformable and complementary activities, meaning that a resource’s productivity may be improved through the investments in other resources. In addition, the diversity of technological learning can provide a major foundation for the organizational routines that reinforce existing core competencies or can facilitate building new ones (Lei, Hitt and Bettis, 1996; Teece, Pisano and Shuen, 1997; Zahra, Ireland and Hitt, 2000) and processes that can lead to moderate knowledge creation (Wadhwa and Kotha, 2006). Thus, this study focuses on technological knowledge diversity as an important moderator of the relationship between intellectual capital components and knowledge creation. The purposes of this study are: (1) to examine relationship between intellectual capital components and knowledge creation; (2) to study interaction effects between intellectual capital components and knowledge creation and (3) to explore technological knowledge diversity moderating effects between each intellectual capital component and knowledge creation. 2. Literature Review Knowledge Creation Knowledge can be divided into two broad types: tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge (Polanyi, 1966). Nelson and Winter (1982) stressed that the corporate world provides special content for the interaction and inter-permeation between tacit and explicit knowledge to produce proprietary knowledge. Based on the perspective of resources-base, all companies comprise knowledge series (Nelson and Winter, 1982; Huber, 1991; Kogut and Zander, 1992; Nonaka, 1994; Grant, 1996). The knowledge resources provide the capacity base for sustaining differentiation and competitive advantages (Dierickx and Cool, 1989). Furthermore, Nonaka (1996) identified two essential features of a knowledge productive organization: tacit which is often highly subjective insights, and personal commitment to the enterprise and its mission. Burt (2003) examined new ideas proposed by a sample of supply chain managers. In his research, an idea that is a new and potentially useful to an individual’s company counts as new knowledge. McFadyen and Cannella (2004) define new knowledge as discoveries about phenomena that were not known previously. They used the biomedical research context, noted new knowledge is something that does not exist anywhere before it is discovered and published by research scientists. Both of the above works took the individual as the unit of analysis. Wadhwa and Kotha (2006) focused on the time period from 1989 to 1999 for the telecommunications equipment manufacturing industry. They operationalized the rate of knowledge creation as the annual count of successful patent application for firm i in year t. Nonaka (1994) developed a dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation which 4 provides an analytical perspective on the component of knowledge creation. The theory explains how knowledge held by individuals, organizations, and societies. Organizations play a critical role in mobilizing tacit knowledge held by individuals and provide the forum for a spiral of knowledge creation. Therefore, the central theme of this study to address the extent of knowledge creation involved at an organizational level after technological knowledge acquisition for the firm. This study defines knowledge creation in terms of new ways of doing things, new ideals, new ways of thinking, and improved problem solving ability to increase productivity. Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Creation Intellectual capital has received considerable attention from academics. Economist Galbraith (1969) was the first to create intellectual capital concept, and described intellectual capital as behavior that requires the exercise of the brain, namely, intellectual capital does not mean just as intellect but demand dynamic intellect-creating activities. Steward (1991, 1997) later adopted a systematic interpretation of intellectual capital, which classified intellectual capital into three main types: human capital, structural capital and social capital. Despite many different terms and definitions related to the theme, there is no widely accepted definition of intellectual capital. However, at least three elements are common: (1) intangibility; (2) knowledge creates value and; (3) effect of collective practice. It is assumed that competitive advantage depends on how efficient the firm in building, sharing, leveraging and using its knowledge. Furthermore, there is a common agreement on that intellectual capital of an organization consists of three main components: human capital, structural capital and social capital (Lonnqvist, et al., 2005; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Seetharaman et al., 2004; Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005; Sveiby, 1997). Reviewing previous studies, intellectual capital has been identified as a set of intangible (resources, capability and competences) that drives the organizational performance and value creation (Roos and Roos, 1997; Bontis, 1998; Bontis et al., 2000; Marr and Roos, 2005). Therefore, this study adopts three dimensions: human capital, structural capital and social capital to explore the relationship between each intellectual capital dimension and knowledge creation in further. Human Capital Human capital is the primary component of intellectual capital (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Stewart, 1997; Bontis, 1998; Choo and Bontis, 2002), because human interaction is the critical source of intangible value in the intellectual age (O’Donnell et al., 2003). On individual level, knowledge generation and transfer depends on the individuals’ willingness. On organizational level, the human capital is the source of innovation and strategic renewal (Bontis, 1998). The characteristics of human capital are creative, bright, skilled employees, with expertise in their roles and functions, who constitute the predominant sources for new ideas and knowledge in an organization (Snell and Dean, 1992). Thus, Nonaka, Toyama and Konno (2000) argued that 5 knowledge creation is a human process, we cannot really answer the question of how to create high-quality knowledge without understanding human factors. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis: H1: The greater human capital in organizations, the higher extent of knowledge creation. Structural Capital Structural capital represents the organization’s capabilities to meet its internal and external challenges. The characteristics of structural capital include infrastructures, information systems, routines, procedures and organizational culture for retaining, package and move knowledge (Cabrita and Vaz, 2006). Organizational knowledge creation represents a process whereby the knowledge held by individuals is amplified and internalized as part of an organization’s knowledge base (Nonaka, 1994). According to Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995), knowledge management requires a commitment to “create new, task-related knowledge, disseminate it throughout the organization and embody it in products, services and systems.” At the organizational level knowledge is generated from internal operations or from outside sources communicating with the corporate structure. Hibbard and Carrillo (1998) claim that organizations adopted information technologies, which supports management of intellectual assets to improve its employees’ value creation. Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno (2000) point out tools can be useful in managing information and supporting knowledge creation. Moreover, when organizations harness their preserved knowledge through structured recurrent activities, they deepen their knowledge and legitimize its perceived value (Katila and Ahuja, 2002). In addition, knowledge cannot be understood without context, and hence knowledge creation requires shared context. Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno (2000) argued that managers should built up the ba (circumstances) by providing time, space, attention, and opportunities for relationship-building of knowledge creation. They can provide physical space such as meeting rooms, cyberspace such as a computer network, or mental space such as common goals to foster interactions. Creating mental space that fosters “love, care, trust, and commitment” among organizational members is important because it forms the foundation of knowledge creation (Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno, 2000). Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis: H2: The greater structural capital in organizations, the higher extent of knowledge creation. Social Capital The concept of social capital was originally used in community studies to describe relational resources embedded in personal ties in the community (Jacobs, 1965). The concept has been applied to a wide range of intra- and inter-organization studies (Burt, 1992; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Yli-Renko, Autio and Spaienza, 2001). Researchers have positioned social capital as a key factor in understanding knowledge creation (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). This 6 study examined the relational dimension of social capital. Key facts of the relational dimension of social capital include share and leverage knowledge among and between partners. An organization’s social capital enhances the quality of group work and richness of information exchange among team members (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). Social capital and knowledge creation will have a positive relationship because social capital directly affects the combine-and-exchange process and provides relatively easy access to network resources (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis: H3: The greater social capital in organizations, the higher extent of knowledge creation. Moderating Effect of Social Capital These three forms of intellectual capital are not independent; conversely, the effect of intellectual capital can be optimized only when these three forms of capital interact and complement one another. Therefore, their interrelationships also play an important role in shaping these influences (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). Accordingly, this study will explore the interaction effects among intellectual capital component and knowledge creation. Individuals and their associated human capital may encourage the questioning of popular norms and originate new ways of thinking, but their unique ideas often need to connect to one another for radical breakthroughs to occur. Dosi (1982) pointed out knowledge creation is a path-dependent process. Knowledge creation requires network members jointly experience problem-solving process and spend time together discussing, reflecting, observing, and interacting (Seufert, vonKrogh and Bach, 1999). While human capital provides organizations with a platform for diverse ideas and thoughts, social capital encourages collaboration both within and across organization (Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). Thus, social capital augments human capital’s role in reinforcing knowledge creation is expected. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses: H4: The greater social capital in organizations, the stronger the influence of human capital on knowledge creation. Groups and team play a substantial role in deploying knowledge within organizations (Nonaka, 1994). Preserved knowledge tends to be used in structured, recurrent activities and is generally perceived to be more reliable and robust than other knowledge. Consequently, structural capital not only improves how an organization’s codified knowledge in patents, databases and licenses is leveraged, but also improves how these knowledge sources are updated and reinforced. An organization’s social capital enhances the quality of group work and richness of information exchange among team members. Thus, social capital augments structural capital’s role in reinforcing knowledge creation. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses: H5: The greater social capital in organizations, the stronger the influence of structural capital on knowledge creation. 7 Moderating Effect of Technological Knowledge Diversity Knowledge creation results from new combinations of knowledge and other resources (Cohen and Levinteal, 1990). Previous research has emphasized that firms seeking to reconfigure their knowledge must move beyond local search and span technological as well as orgnizational boundaries (Rosenkopf and Nerkar, 2001). To accumulate the necessary knowledge, many organizations turn to external activities such as alliances, joint ventures, mergers and acquistions, and corporate venture capital investment (Schildt, Maula, and Keil, 2005, Wadhwa and Kotha, 2006). Access and exposure to diverse knowledge domains enlightens organizations about new ways by which existing problems can be solved (Rosenkopf and Nerkar, 2001). Access to new external knowledge can influence knowledge creation within the firms. The firms may use new information to support, complement or agument their internal R&D capabilities, exploit it to enter new markets or introduce new products earlier than competitors who lack access to new external knowledge (Chesbrough and Tucci, 2003; Maula et al., 2003), and improve existing products by adding new features and functions (Keil et al., 2004). In addition, access to new information improves the absorptive capacity of the firms (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990) and creates a basis for their future assimilation of additional external knowledge (Ahuja and Katila, 2001). If an organization’s knowledge base is narrow, its core capabilities are likely to evolve into core rigidities(Lenonard-Barton, 1992). A broader knowledge base provides the firm with increased flexibility and adaptability to environmental changes(Volberda, 1996). In other words, knowledge diversity engender a fluid mind-set conducive to new idea genertion. Thus, technological knowledge diversity plays an important role in whether a firm is able to maximize learning from internal and external sources to create new knowledge (Wadhwa and Kotha, 2006). Thus, this study expects technological knowledge diversity augments intellectual capital’s role in enhancing knowledge creation. The following hypothesis is proposed: H6: The greater technological knowledge diversity in organizations, the stronger the influence of human capital on knowledge creation. H7: The greater technological knowledge diversity in organizations, the stronger the influence of structural capital on knowledge creation. H8: The greater technological knowledge diversity in organizations, the stronger the influence of social capital on knowledge creation. 3. Research Method Research Framework Based on the above discussion, this study proposed a conceptual model. Fig. 1 illustrates the 8 research framework. The three components of intellectual capital influence on knowledge creation directly. However, these influences are not always isolated, given that human capital, structural capital, and social capital are often intertwined in organizations. Therefore, their interrelationships also play an important role in shaping these influences. In addition, technological knowledge diversity plays an important role in whether a firm is able to maximize learning from external sources to create new knowledge. Thus, this study examines that technological knowledge diversity augments intellectual capital’s role in enhancing knowledge creation. Moderating Effects Technology Knowledge Diversity Intellectual Capital Human Capital Structural Capital Social Capital Knowledge Creation Interactive Effects Human Capital x Social Capital Structural Capital x Social Capital Fig. 1 Conceptual Structure for this Research Variable Definition and Measurement Dependent variable. The knowledge creation, our dependent variable, was operationalized by the research of Nonaka (1991, 1994), as well as Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995). Thus, this study defines knowledge creation in terms of new ways of doing things, new ideals, new ways of thinking, and improved problem solving ability to increase productivity. The four items assessing the extent of knowledge creation were based on the original discussions of knowledge creation (Nonaka, 1991, 1994). A five-point scale was adopted to measure the extent of the questionnaire items, with one indicating "strongly disagree" and five indicating "strongly agree." Independent variable. The intellectual capital, our independent variable, was operationalized by previous studies (Roos and Roos, 1997; Bontis, 1998; Bontis et al., 2000; Marr and Roos, 2005). This study defines intellectual capital as a set of intangible resources, capability and competences that drives the organizational knowledge and value creation and it consists of three main components: human capital, structural capital and social capital (Lonnqvist, et al., 2005; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Seetharaman et al., 2004; Subramaniam 9 and Youndt, 2005; Sveiby, 1997). The measurement of human capital was based on the research of Huang (2002) and Van Buren (1999). Human capital includes attracting and maintaining human resources, training, and employee evaluation. Nine items are used to assess human capital. The measurement of structural capital was based on the research of Davenport and Prusak (1998) and Walsh and Ungson(1991). Eight items are used to assess an organization’s ability to appropriate and store knowledge in physical organization-level condition such as the hardware and software management, system building, operational evaluation, structure, processes and culture. And lastly, social capital drew the core ideas of the social structure literature (Burt, 1992) as well as on the more specific knowledge management literature (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000). Six items are used to assess an organization’s overall ability to share and leverage knowledge among and between networks of employees, government, customers, alliance partners, suppliers and technical collaboration. A five-point scale was adopted to measure the extent of the questionnaire items, with one indicating "strongly disagree" and five indicating "strongly agree." Moderating variable. The technological knowledge diversity, our moderating variable, was operationalized by previous studies (Wadhwa and Kotha, 2006). This study defines technological knowledge diversity as the numbers of method adopted by a business to acquire key technology by internal development or external transfer. To measure the degree of technological knowledge diversity by calculating the number of a business to acquire key technology by internal development or external transfer, we identified five types of technology acquisition: Independent R&D, technical collaboration, technology purchase, know-how purchase, and patent rights through licensing. Research Subjects and Data Collection Data were collected from the samples of the Taiwanese Biotechnology Industry. Intellectual capital is an organizational construct that requires “strategic awareness” from informants to answer the questionnaire. Therefore, this study selected the managers of R&D department to reply the questionnaire. The questionnaires were mailed to (1) members of the Taiwan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association and the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association of Chinese Medicine. (2) Biotechnology firms listed in the 2005 survey of the Taiwan Institute of Economic Research. A total of 100 questionnaires were mailed to pharmaceutical companies, 210 to Chinese medicine pharmaceuticals and 370 to biotechnology companies. To increase response rates, two follow-ups (personal visits and telephone calls) were carried out. 18, 25 and 60 valid respondents were obtained, respectively, from the TPMA, PMACM and biotechnology firms. A total of 103 valid responses were obtained, after 6 weeks, represent a valid response rate of 15%. An analysis of respondents and non respondents showed no differences in industry members, number of employees, and revenues. 10 Measurement Properties This study assessed construct reliability by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each of the intellectual capital and knowledge creation. According to the test result, human capitalαhas coefficient 0.83, structural capital 0.89, social capital 0.84 and knowledge creation α has coefficient 0.91. All of the scales were above the suggested value of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978). Thus, we concluded the measures utilized in the study were valid and internally consistent. Using AMOS5.0, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of three aspects of intellectual capital and knowledge creation. Overall, the CFA results suggested that intellectual capital model provided a moderate fit for data and that the knowledge creation model provided a good fit for the data. Table 1 summarizes the results of confirmatory factor analyses on the measurement model. As the factor loading indicate, the measurement model performed very well. The standardized factor loading are all above 0.53, while recommended minimum in the social sciences is usually 0.40 (Ford, McCallum and Tait, 1986). The average variances extracted range from 0.72 to 0.86, while recommended minimum 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The measurement model can be used to evaluate discriminate validity. Constructs demonstrate discriminate validity if the variance extracted for each is higher than the squared correlation between the constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). We examined each pair of constructs in our measurement model and found that all demonstrate discriminate validity. Convergent validity is also evident: positive correlations exist among the three intellectual capital constructs, as is expected for constructs representing different dimensions of the same underlying. Table 2 reports means, standard deviations, and correlations for the variables of the study. 4. Results Descriptive Statistics Table 2 provides the means, standard deviations, and correlation for the variables used in the models. We found knowledge creation to be positively and significantly corrected with all of the dimensions for intellectual capital. Structural capital, in particular, was strongly correlated with the dependent variable (r = 0.694). Technological knowledge diversity was positively and significantly corrected with dependent variable. 11 Table 1 Measurement Model Factor name Items Std. Loading St. Error t Value Human Capital HC1 HC2 HC3 HC5 HC6 HC7 SC2 SC4 SC5 SC6 SC7 SC8 SC9 SC10 SC1 SC2 SC3 SC4 SC5 SC8 KC1 KC2 KC3 KC4 0.57 0.75 0.54 0.68 0.76 0.76 0.62 0.57 0.59 0.76 0.85 0.87 0.74 0.70 0.65 0.55 0.73 0.93 0.72 0.53 0.80 0.85 0.90 0.84 0.15 0.13 0.12 0.12 0.13 5.29 7.17 4.97 6.39 7.24 0.21 0.23 0.21 0.19 0.18 0.21 0.19 5.68 5.22 5.43 6.95 7.71 7.88 6.74 0.27 0.23 0.25 0.32 0.26 4.59 4.12 4.90 5.39 4.83 0.12 0.12 0.13 9.22 9.88 9.11 Structural Capital Social Capital Knowledge creation Table 2 Cronbach’s Alpha Composite Reliability Average Variance Extracted 0.83 0.94 0.78 0.89 0.95 0.72 0.84 0.95 0.81 0.91 0.95 0.86 The Correlations and Descriptive Statistics Variable KC Knowledge Creation (KC) 1.00 HC StC SoC TKD Human Capital (HC) .654** 1.00 Structural Capital (StC) .694** .675** 1.00 Social Capital(SoC) .593** .625** .541** 1.00 Technological Knowledge Diversity (TKD) . 476** .273** .294** .428** 1.00 Mean 3.81 3.39 3.89 3.49 3.22 S.D. .70 .57 .60 .67 .65 Note: **p<0.01, *p<0.05 12 Relationship between Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Creation Table 3 shows that, using model 1, all dimensions of intellectual capital were positively and significantly influence on knowledge creation, and explain 55.3% of total variance. Therefore, these results support Hypothesis 1, 2, 3. This research examined the multicollinearity. Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black (1998) suggest that tolerance and VIF threshold values are 0.1 and 10, respectively. From model 1 in Table 3, the VIF values of all predictive variables are far away from threshold values. In other words, there is less multicollinearity among predictive variables. Table 3 depicts the results for overall model, comprising main and interaction effects. The Ra2 for model 2 increased from 0.553 to 0.613, attributable to the moderating effects. As expected, social capital significantly positively moderates the relationship between structural capital and knowledge creation, thereby providing support for hypothesis 5. However, the social capital by human capital interaction was not significantly related to knowledge creation, thus was not providing support for hypothesis 4. Table 3 Relationship between Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Creation Knowledge Creation Dep. Var. Model 1 Ind. Var. Model 2 Beta St. Error p. VIF Beta St. Error p. Human Capital (HC) 0.236 0.128 0.025 2.22 0.248 0.129 0.019 Structural Capital (StC) 0.415 0.113 0.000 1.92 0.281 0.150 0.030 Social Capital (SoC) 0.220 0.095 0.017 1.72 0.295 0.024 0.035 Human Capital x Relational Capital Structural Capital x Relational Capital F 38.89 49.85 Ra2 0.553 0.613 △Ra2 0.06 Moderating Effects of Technological Knowledge Diversity on Knowledge Creation To test the moderating effects on the technological knowledge diversity between intellectual capital and knowledge creation, we used moderated regression analysis. Table 4 depicts the results for overall model, comprising main and interaction effects. The Ra2 for model 13 4 increased from 0.590 to 0.620, attributable to the moderating effects. Hypothesis 7 argues that technology knowledge diversity moderates the relationship between structural capital and knowledge creation. From model 4 in Table 4, technological knowledge diversity by structural capital was significantly related to knowledge creation, thereby providing support for hypothesis 7. But, technological knowledge diversity by human capital and social capital were statistically insignificant (Table 4, model 4). Thus, Hypothesis 6 and 8 were not supported. Table 4 Moderating Effects of Technological Knowledge Diversity on Knowledge Creation Knowledge Creation Dep. Var. Model 3 Ind. Var. Model 4 Beta St. Error p. VIF Beta St. Error p. Human Capital (HC) 0.249 0.121 0.013 2.23 0.298 0.113 0.002 Structural Capital (StC) 0.388 0.107 0.000 1.93 0.227 0.132 0.046 Social Capital (SoC) 0.124 0.096 0.177 1.91 Technological Knowledge Diversity 0.241 0.079 0.001 1.23 0.361 0.020 0.001 Human Capital x Technological Knowledge Diversity Structural Capital x Technological Knowledge Diversity Social capital x Technological Knowledge Diversity F 45.07 55.91 Ra2 0.590 0.620 △Ra2 0.03 5. Discussion Results of Research The purpose of this study was to theoretically and empirically examine the link between intellectual capital and creation. This study provides evidence that all dimensions of intellectual capital were positively and significantly influence on knowledge creation. This finding proves that social capital as a key factor in understanding knowledge creation (McFadyen and Canella, 2004; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). Furthermore, this finding meets the argument of knowledge creation is a human process (human capital) raised by Nonaka, Toyama and Konno (2000) as 14 well as the argument proposed by Katila and Ahuja (2002) that when organizations harness their preserved knowledge through structured recurrent activities (structural capital), they deepen their knowledge and legitimize its perceived value. Additionally, this research examines that social capital augments human capital’s and structural capital’s role in reinforcing knowledge creation. The research finds that social capital by structural capital interaction was significantly related to knowledge creation. This finding meets the argument of managers should built up the ba (structural capital) by providing time, space, attention, and opportunities for relationship-building (social capital) of knowledge creation proposed by Nonaka, Toyama, and Konno (2000). But the social capital by human capital interaction was not significantly related to knowledge creation. Therefore, this study partly proves empirically that intellectual capital is a phenomenon of interactions, the findings of this study is different from previous related studies (Cabrita and Vaz, 2006; Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005). Technological knowledge diversity, this research’s second potential moderator, moderates the main relationship partly. In this work’s augment for moderation, the study assumed that technological knowledge diversity augments intellectual capital’s role in enhancing knowledge creation. The research finds that technology knowledge diversity moderates the relationship between structural capital and knowledge creation. But, technological knowledge diversity by human capital and social capital were statistically insignificant. Therefore, this study partly proves empirically that technological knowledge diversity is a phenomenon of moderations. The findings of this study are similar to previous related studies (Wadhwa and Kotha, 2006). Implication The findings of this study have several implications. First, previous studies have examined the relationships between social capital (McFadyen and Canella, 2004) as well as external venturing (Wadhwa and Kotha, 2006) and knowledge creation. This research is one of the few empirical efforts to examine the relationship between intellectual capital and knowledge creation. Second, previous works of the relationship between intellectual capital and innovation (Darroch and McNaughton, 2002; Gleoet and Terziovski, 2004; Liu, Chen and Tsai, 2005; McAdam, 2002; Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005) as well as organizational performance and value creation (Bontis, 1998; Bontis et al. 2000; Cabrita and Vaz, 2006; Marr and Roos, 2005; Roos and Roos, 1997) have been studied. But it is few to explore the relationship between intellectual capital and knowledge creation. The findings of this study provide evidence of the critical role that intellectual capital plays in explaining knowledge creation. Third, previous intellectual capital studies recommend generalization of their results to other countries. This study proves that intellectual capital is substantively and significantly related to knowledge creation in Taiwan’s biotechnology industry. Fourth, this study partly proves empirically that intellectual capital is a 15 phenomenon of interactions, i.e., the social capital by human capital interaction was not significantly related to knowledge creation. A possible explanation for the lack of moderation, as Lynn (1999) stressed that human capital resembles a root, absorbing all nutrition, structural capital is like a trunk, transferring and transmitting nutrition, and relational (social) capital is like leaves, conveying environmental produce elements. Fifth, this study partly proves empirically that technological knowledge diversity is a phenomenon of moderations. A possible explanation for the lack of moderation is that the sample firms may lack the assumed diversity. In other words, the firms may have been overly focused on certain acquiring type of technological knowledge they may have exhausted the reorganizing pool from new knowledge acquisition. Limitations and Future Research This study is not without limitations. This research’s valid sample size was relatively small, given the number of variables in this study’s models. Another limitation was that this research depended on perceptual measures because it was difficult to obtain relevant objective measures capturing the variations in intellectual capital and knowledge creation. This study also recognizes that the link between intellectual capital and knowledge creation is complex and contingent on several multidimensional organizational actions, for example, organizational learning as well as specific strategic activities. However, this study did not take the possible influences of such action into consideration. Nonetheless, by synthesizing two different literature streams, i.e. intellectual capital and knowledge creation, this study has initialized efforts to understand the multidimensional intellectual capital- knowledge creation linkage. The results of this study suggest several avenues for future research on the knowledge creation. One such approach would be to focus more closely on the link between social capital and knowledge creation. For example, Adler and Kwon (2002) proposed various contingencies governing the value of social capital could be applied to further knowing of the influences of social capital on knowledge creation. A fertile area for future research is the moderating effects. For example, the development and testing of a framework for technological learning (Lei, Hitt and Bettis; Teece, Pisano and Shuen, 1997; Zahra, Ireland and Hitt, 2000) moderates the relationship between intellectual capital and knowledge creation. Additionally, there is a need for research into the moderating effects of knowledge integration (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Zahra, Ireland and Hitt, 2000) on the relationship between intellectual capital and knowledge creation. 16 References 1. Adler, P. S. and Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social Capital: Prospects for A New Concept. Academy of Management Review, 17, 17-40. 2. Ahuja, G. (2000). Collaborative Networks, Structural Holes, and Innovation: A Longitudinal Study. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45. 425-455. 3. Ahuja, G. and Katila, R. (2001). Technological Acquisitions and the Innovation Performance of Acquiring Firms: A Longitudinal Study. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 197-220. 4. Bontis, N. (1998). Intellectual Capital: An Exploratory Study That Develops Measures and Models. Management Decision, 36(2), 63-76. 5. Bontis, N. Keow, W. C. C. and Richardson, S. (2000). Intellectual Capital and Business Performance in Malaysian Industries. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 1(1), 85-100. 6. Brooking, A. (1996). Intellectual Capital: Core Assets for the Third Millennium Enterprise, International Thomson Business Press, London. 7. Burt, R. S. (2003). Social Origins of Good Ideas. Working Paper, University of Chicago. 8. Cabrita, M. and Vaz, J. (2006). Intellectual Capital and Value Creation: Evidence from the Portuguese Banking Industry. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 4(1), 11-20. 9. Chesbrough, H. W. and Tucci, C. L.(2003). Corporate Venture Capital in the Context of Corporate R&D. Working Paper, University of California, Berkely. 10. Choo, C. W. and Bontis, N. (2002). The Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital and Organizational Knowledge. Oxford University Press, Inc., New York. 11. Cohen, W. M. and Levinteal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 128-152. 12. Darroch, J. and McNaughton, R. (2002). Examining the Link between Knowledge Management Practices and Types of Innovation. Journal of Intellectual Capital. 3(3), 210-222. 13. Davenport, T. H. and Prusak, L. (1998). Working Knowledge. HBS Press, Cambridge. 14. Dierickx, I. and Cool, K. (1989). Asset Stock Accumulation and Sustainability of Competitive Advantage, Management Science. 35, 1504-1541. 15. Dosi, G. (1982). Technological Paradigms and Technological Trajectories. Research Policy, 11, 147-162. 16. Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. S. (1997). Intellectual Capital: Realizing Your Company’s True Value by Finding its Hidden Roots. HarperCollins Publishers, New York. 17. Ford, J. C., McCallum, R. C. and Tait, M. (1986). The Application of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Applied Psychology: A Critical Review and Analysis. Personnel Psychology, 39, 291-314. 18. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal Marketing Research, 18(1) 39-50. 19. Gloet, M. and Terziovski, M. (2004). Exploring the Relationship between Knowledge Management Practices and Innovation Performance. Journal of Manufacturing 17 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. Technology Management, 15(5), 402-409. Grandstrand, O. (1998). Towards A Theory of the Technology-Based Firm? Research Policy, 29, 1061-1080. Grant, R. M. (1996). Prospering in Dynamically-Competitive Environments: Organizational Capacity as Knowledge Integration. Organization Science, 7, 375-387. Gupta, A. K. and Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge Management’s Social Dimension: Lessons from Nucor Steel. Sloan Management Review, 42(1), 71-79. Guthrie, J. (2001). The Management, Measurement and the Reporting of Intellectual Capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2(1), 27-41. Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L. and Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th edition, Prentice-Hall International, Inc. Hansen, M. T. (1999). The Search-Transfer Problem: The Role of Weak Ties in Sharing Knowledge across Organization Subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 82-111. Huang, J. C. (2002). Human Resource Management System and Organization Performance: Intellectual Capital Perspective. Management Review, 19(3), 415-450, (in Chinese). Huber, G. P. (1991). Organizational Learning: The Contributing Processes and the Literature. Organizational Science, 2(1), 88-115. Hussi, T. and Ahonen, G. (2002). Managing Intangible Asset? A Question of Integration and Delicate Balance? Journal of Intellectual Capital, 3(2), 277-286. Jacobs, D. (1965). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Penguin: New York. Katila, R. and Ahuja, G. (2002). Something Old, Something New: A Longitudinal Study of Research Behavior and New Product Introduction. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 1183-1194. Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1996). What Firms Do? Coordination, Identity, and Learning. Organization Science, 7(3), 502-518. Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the Firm, Combinative Capabilities, and The Replication of Technology. Organization Science, 3(2), 383-397. Lei, D. Hitt, M. A. and Bettis, R. (1996). Dynamic Core Competences through Meta-Learning and Strategic Context. Journal of Management, 22, 549-569. Lenonard-Barton, D. (1992). Core Capabilities and Rigidities: A Paradox in Managing New Product Development. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 111-125. Liu, P-L., Chen, W-C. and Tsai, C-H. (2005). An Empirical Study on the Correlation between the Knowledge Management Method and New Product Development Strategy on Product Performance in Taiwan Industries. Technovation, 25, 637-644. Lynn, B. E. (1999). Culture and Intellectual Capital Management. International Journal of Technology Management, 18(5/6/7/8), 590-603. Marr, B. and Roos, G. (2005). A Strategy Perspective on Intellectual Capital. in Perspectives on Intellectual Capital-Multidisciplinary Insights into Management, Measurement and Reporting, Marr, B. (Ed.). Butterworth- Heinemann, Oxford, 28-41. Marr, B. and Schiuma, G. (2001). Measuring and Managing Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Assets in New Economy Organizations. In Bourne, M.(ed.) Handbook of Performance Measurement, GEE Publishing, Ltd., London. 18 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. Maula, M., Keil, T. and Zahra, S. A. (2003). Corporate Venture Capital and Recognition of Technological Discontinuities. The Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle. Mayo, A. (2001). The Value of the Enterprise: Valuing People As Assets - Monitoring, Measuring, Managing, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London. McAdam, R. (2002). Knowledge Management as A Catalyst for Innovation within Organizations: A Qualitative Study. Knowledge and Process Management, 7(4), 233-214. McFadyen, M. A. and Canella, A. A. (2004). Social Capital and Knowledge Creation: Diminishing Returns of the Number and Strength of Exchange Relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5) 735-746. Nahapiet, J. & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23, 242-266. Nelson, R. and Winter, S. (1982). An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change, Cambridge, MA: Belknap. Nonaka, I. (1991). The Knowledge-Creating Company. Harvard Business Review, 69(6), 96-104. Nonaka, I., (1994). A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organization Science, 5(1) 14-37. Nonaka, I. (1996). The Knowledge-Creating Company. (Ed.) Starkey, K. How Organizations Learn. International Thompson Business press, London. Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge-Creating Company. Oxford University Press, New York. Nonaka, I., Toyama, R. and Konno, N. (2000). SECI, Ba and Leadership: A Unified Model of Dynamic Knowledge Creation. Long Range Planning, 33(1), 5-34. Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric Theory, 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York. O’Donnell, D., O’Regan, P., Coates, B., Kennedy, T., Keary, B. and Berkery, G. (2003). Human Interaction: The Critical Source of Intangible Value. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 4(1), 82-99. Polanyi, M. (1966). The Tacit Dimension. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. Roos, G. and Roos, J. (1997). Measuring Your Company’s Intellectual Performance. Long Range Planning, 30(3), 413-426. Roos, J., Roos, G., Dragonetti, N. Edvinsson, L. (1997). Intellectual Capital: Navigating the New Business Landscape, Macmillan Press Ltd., London. Rosenkopf, L. and Nerkar, A. (2001). Beyond Local Search: Boundary-Spanning, Exploration, and Impact in the Optical Disk Industry. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 287. Schildt,H. Maula, M. V. J. and Keil, T. (2005). Explorative and Exploitative Learning from External Corporate Ventures. Entrepreneuship Theory and Practice, 29, 493-515. Seetharaman, A. Lock, T, Low K. and Saravanan, A. S. (2004). Comparative Justification on Intellectual Capital? Journal of Intellectual Capital, 5(4), 522-539. Sena, J. A. and Shani, A. B. (1999). Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Creation: Towards an Alternative Framework. Knowledge Management Handbook, Leibowitz, J. (ed.), CRC Press LLC. 19 59. 60. 61. 62. 63. 64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. 71. 72. Seufert, A., vonKrogh, G. and Bach, A. (1999). Towards Knowledge Networking. Journal of Knowledge Management. 3(3), 180-190. Snell, S. A. and Dean, J. W. (1992). Integrated Manufacturing and Human Resources Management: A Human Capital Perspective. Academy of Management Journal. 35, 467-504. Spender, J-C. (1996). Making Knowledge the Nasis of A Dynamic Theory of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, Winter Special Issue 17, 45-62. Steward, T. A. (1991). Brainpower: How Intellectual Capital Is Becoming America's Most Valuable Assets. Fortune, June, 44-60. Stewart, T. A. (1997). Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations. Currency/Doubleday, New.York. Subramaniam, M. and Youndt, M. A. (2005). The Influence of Intellectual Capital on the Ttypes of Innovative Capabilities. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 450-463. Sveiby, K. (1997). The New Organizational Wealth. Berrett Koehler, San Francisco. Teece, D. J. Pisano, G. and Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal. 18, 359-533. Van Buren, M. E., (1999). A Yard Stick for Knowledge Management. Training & Development, 53(5), 71-78. Volberda, H. W. (1996). Toward the Flexible Form: How to Remain Vital in Hypercompetitive Environmnets. Organization Science, 7, 359-387. Wadhwa, A and Kotha, S. (2006). Knowledge Creation through External Venturing: Evidence from the Telecommunications Equipment Manufacturing Industry. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 819-835. Walsh, J. P. and Ungson, G. R. (1991). Organizational Memory. Academy of Management Review, 16, 57-91. Yli-Renko, H. Autio, E. and Spaienza, H. J. (2001). Social Capital, Knowledge Acquisition and Knowledge Exploitation in Young Technology-Based Firms. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 587-613. Zahra, S. A., Ireland, R. D. and Hitt, M. A. (2000). International Expansion by New Venture Firms: International Diversity, Mode of Market Entry, Technological Learning, and Performance. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 925-950. 20