Name: Date: Japanese Culture Directions: Read the articles and

advertisement

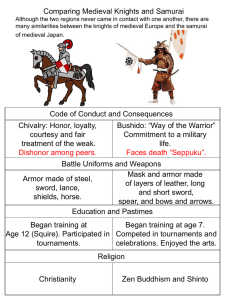

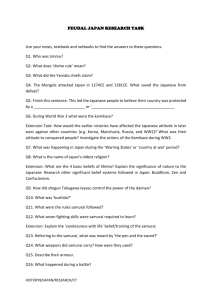

Name:____________________________________________ Date:______________________________ Japanese Culture Directions: Read the articles and complete the graphic organizer that follows. Article #1: Samurai of Feudal Japan: 13th-19th Centuries (Complete with Cluster Web) The samurai were the warrior class of feudal Japan between the 13th and 19th centuries C.E. The word "samurai" is derived from the Japanese word saburau, "to serve." The core of the samurai ethical code, known as Bushido, glorified heroism, courage, honor, and loyalty to one's lord. The samurai came into existence in the early 13th century with the establishment of a feudal society in Japan. As in medieval Europe, the large landowners dominated the economy in an agricultural society and therefore had sufficient monetary resources to pay for the best in military supplies. The ability to own armor, horses, and superior weaponry brought one an exalted social status to be carefully maintained. The samurai thus were dedicated to perfecting their martial skills and living by a strict code of honor that supported the feudal system. At the height of the samurai's preeminence, loyalty to one's overlord and the ability to defend his property and status, even to the detriment of one's own property and status, became the pinnacle of honor. The original soldiers of Japan were called bushi ("warrior"), from the Japanese pronunciation of a Chinese character signifying a man of letters and/or arms. The rise of those warriors to the status of a special class began with an interclan struggle in the late 1100s. The Genji, or Minamoto, and Heike, or Taira, clans were maneuvering for influence in the imperial court, and the Heike managed to obtain the upper hand. In the ensuing Gempei War, the Genji clan was almost completely destroyed, but Minamoto Yoritomo, a son of the clan leader, managed to escape northward from the area of the capital city, Kyoto. When Yoritomo reached his majority, he rallied his remaining supporters and allied with the clans of the northern part of the Japanese mainland that looked down on the imperial clans, which they considered weak and effete. Yoritomo's return renewed the fighting, and in the second struggle, the Heike were defeated. In 1192, Yoritomo was named shogun, the supreme military position as personal protector of the emperor. As the emperor had more figurative than literal power, the position of shogun came to wield real authority in Japan. During the so-called Kamakura shogunate, the samurai established their distinctive culture and code of conduct. Artistic aspects of samurai culture, including flower arranging and the Japanese tea ceremony, further developed during the subsequent Ashikaga shogunate, which lasted until the 16th century. As Japan's emperor and central government exercised less control over time, the local landed gentry, or daimyos, came to prominence and wielded real power in the countryside. By the 16th century, the samurai came to be a true warrior class of professional, full-time soldiers, who were sworn to their daimyo overlords. As warriors, the samurai tended to dominate the command positions as heavy cavalry, while the mass of soldiers became pikemen. Japanese armies also had bowmen, although most archery was practiced from horseback and therefore in the province of the samurai. For the samurai, the sword became a symbol of their position, and they were the only soldiers allowed by law to carry two swords, a crime punishable by execution. The two swords were the katana, or long sword (averaging about a three-foot blade), and the wakizashi, or short sword (with a blade normally 16-20 inches long). Both swords were slightly curved with one sharpened edge and a point; they were mainly slashing weapons, although they could be used for stabbing. The short sword was also used in seppuku, the samurai's ritual suicide in cases of dishonor. The sword and its expert use attained spiritual importance in the samurai's life. In addition, the samurai wore elaborate suits of armor, mainly made of strips of metal laced with leather. The finished product was lacquered and decorated to such an extent that not only was it weatherproof and resistant to cutting weapons, but it also became almost as much a work of art as a fine sword. Armor proved unable to stop musket balls, however, and became mainly ceremonial after 1600. By that time, the samurai class, which had over time blended the hardiness of the country warrior with the culture of the court warrior, was the pinnacle of culture, learning, and power. Yet without the almost constant warfare that preceded the Tokugawa shogunate, established in 1603, the samurai had fewer and fewer chances to exercise their profession of arms. They became bureaucrats and therefore could not be rewarded in combat nor expand their holdings through warfare. Moreover, the samurai class increased in numbers, and the increasingly bloated bureaucracy brought about their economic slide. Article #2: Women Warriors in Ancient and Medieval Japan (Complete with Garden Gate chart ) Women played interesting roles as rulers and fighters in ancient and medieval Japan. The great Japanese epic, Heike Monogatari (Tale of the Heike), celebrates many women warriors. The naginata, a heavy blade on the end of a staff, was their favored weapon. If the naginata were to fail, female samurai carried a long dagger called a kai-ken for last-ditch defense or, if capture seemed inevitable, for ritual suicide. According to Japanese tradition, in the fourth century CE, Empress Jingo-Kogo, although pregnant, led her forces in a victorious campaign against Korea. The medieval warrior Lady Yatsushiro also reputedly went into battle while pregnant, mounted on horseback and accompanied by her attack-wolf, Nokaze. The most renowned female warrior of medieval Japan, however, was Tomoe Gozen. Among her legendary exploits was the presentation of the head of the shogun Uchida Iyeyoshi to her husband. Gozen decapitated Iyeyoshi in hand-to-hand combat. She also single-handedly defended a bridge against a multitude of attackers using only her naginata. Other legends assert that after the defeat of her husband, Gozen fled with his severed head and cast herself into the sea in order to prevent her husband from being dishonored, to avoid the dishonor to herself of possible capture, and to die with her husband. Among the many women warriors recorded in Japanese history are Masaki Hojo, the widow of the first Minamoto shogun; Fujinoye, who defended Takadachi Castle in 1189 by blocking the stairs with her naginata; and Hangaku, the daughter of a samurai, who rained down deadly arrows on the attackers of Echigo Castle in 1201. Dressed in men's clothing, Hangaku mounted the tower of the castle and "all those who came to attack her were shot down by her arrows which pierced them either in their chests or their heads. Their horses were killed and their shields were broken into pieces from their arms." An archer finally avoided her by circling to the rear of the castle and, undetected by Hangaku, was able to wound her with an arrow. The shogun Yoriye described her while in captivity as "fearless as a man and beautiful as a flower." According to Inazo Nitobe, a 19th-century commentator on Bushido (the code of the samurai): “Young girls . . . were trained to repress their feelings, to indurate their nerves, to manipulate weapons—especially the long-handled sword called nagi-nata, so as to be able to hold their own against unexpected odds. . . . [A] woman owning no suzerain of her own, formed her own bodyguard. With her weapon she guarded her personal sanctity. . . . Girls, when they reached womanhood, were presented with dirks (kai-ken, pocket poniards), which might be directed to the bosom of their assailants, or, if advisable, to their own. . . . Her own weapon lay always in her bosom. It was a disgrace to her not to know the proper way in which she had to perpetrate selfdestruction.” Nitobe, however, cautioned that "masculinity" was not the Bushido ideal for women. He saw no contradiction between being a warrior and being feminine. He asserted that central to the code was self-sacrificing service and that for women this was primarily to home and family. For a woman, he wrote, "the domestic utility of her warlike training was in the education of her sons." : WEB1 | Client IP: 206.166.54.246 | Session ID: et0wz530qv3slyaomocaxizp | Token: MLA Cook, Bernard. "women warriors in ancient and medieval Japan." World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 8 Dec. 2010. "s Samurai." World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras. ABC-CLIO, 2010. Web. 8 Dec. 2010.