here - The Communication Trust

advertisement

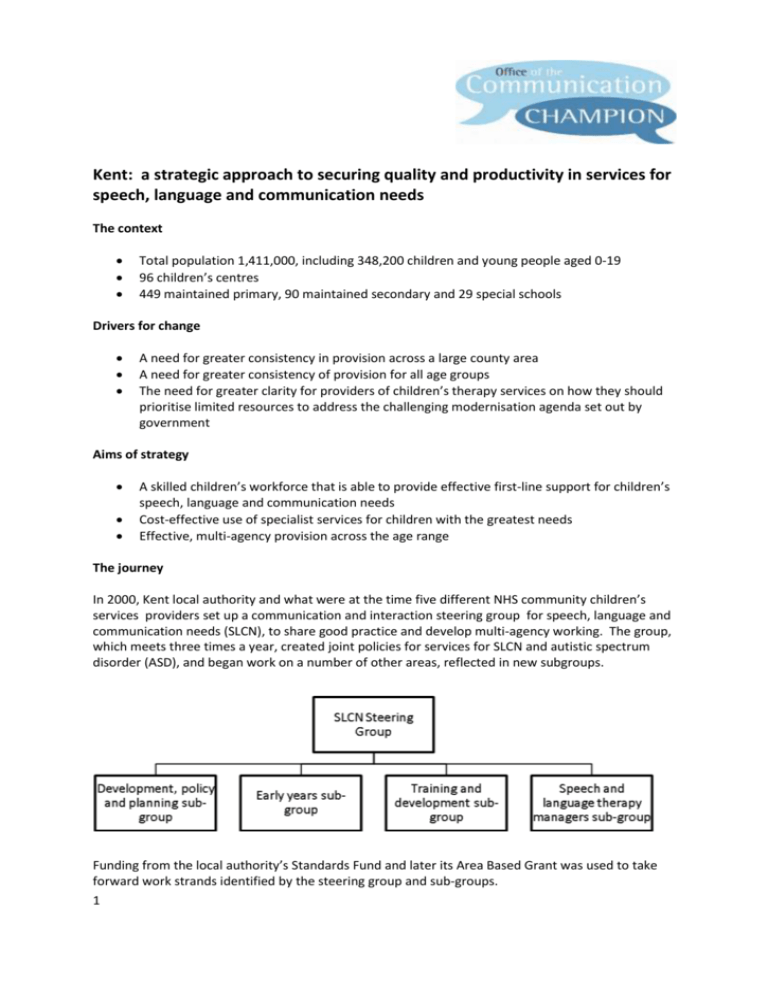

Kent: a strategic approach to securing quality and productivity in services for speech, language and communication needs The context Total population 1,411,000, including 348,200 children and young people aged 0-19 96 children’s centres 449 maintained primary, 90 maintained secondary and 29 special schools Drivers for change A need for greater consistency in provision across a large county area A need for greater consistency of provision for all age groups The need for greater clarity for providers of children’s therapy services on how they should prioritise limited resources to address the challenging modernisation agenda set out by government Aims of strategy A skilled children’s workforce that is able to provide effective first-line support for children’s speech, language and communication needs Cost-effective use of specialist services for children with the greatest needs Effective, multi-agency provision across the age range The journey In 2000, Kent local authority and what were at the time five different NHS community children’s services providers set up a communication and interaction steering group for speech, language and communication needs (SLCN), to share good practice and develop multi-agency working. The group, which meets three times a year, created joint policies for services for SLCN and autistic spectrum disorder (ASD), and began work on a number of other areas, reflected in new subgroups. Funding from the local authority’s Standards Fund and later its Area Based Grant was used to take forward work strands identified by the steering group and sub-groups. 1 Historically, the Kent area had no consistent standard of NHS commissioning for children’s therapy services. Services wanted greater clarity on what their focus should be, given constrained resources providing services across a very large area. In 2007, the senior commissioning manager for disabled children in West, Eastern and Coastal Kent Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) initiated work to develop cross-Kent standards. The SLCN steering group led the work on speech and language services, taking as its ultimate focus the whole continuum of provision rather than just the NHS speech and language therapy (SLT) resource, and specifying what should be provided at universal and targeted as well as specialist levels. There are now, in 2010, four rather than five NHS providers in Kent. The resources available to deploy across the county are the SLT services, 13 advisory teachers employed by the local authority, a number of mainstream school SLCN resourced provisions that are now moving into an outreach role, and special schools. There are strong partnerships with the voluntary sector; ICAN have been a key partner. Strategically, SLCN is being given a high priority in the county, with plans for 12 Communication Champions linked to the 12 council districts, as well as an overall Children’s Trust Communication Champion. The wider context The work on SLCN provision sits within a wider context of work on SEN and disability. Kent’s elected members have committed funding to develop multi-agency specialist hubs. These involve special schools and will bring together services on a ‘one stop shop’ model, providing assessment, intervention, review, training and the coordination of short breaks for families with disabled children. 2 The workforce development strategy The steering group implemented a three-tier model of training, in conjunction with Canterbury Christchurch University. Training tier Awareness Training used Language for Learning, Worcestershire’s package of six two and a half hour sessions. Core Eight, one day sessions, locally developed. Postgraduate Postgraduate certificate that is part of a Masters programme. Target audience Teachers plus teaching assistants (TAs). TAs are not accepted on the course unless partnered by a teacher. Teacher and TA pairs. Teachers Features Training leads to an action/development plan which is followed up after three months. Training covers more theory than Language for Learning. Each session has followup tasks which when completed lead to accreditation. Focuses on critical thinking/evaluation as well as theory and practice. A three-hour SENCO training package is also provided. All training is delivered jointly by SLTs and specialist teachers. 52 people undertook a four day course to enable them to be accredited trainers for the Language for Learning course. There is a similar three-tier training model for ASD, with the government’s Inclusion Development Programme forming the basis for the awareness level training. The steering group keeps track of where individuals or whole schools have received training, and build this into the workforce strategy. Over a three year period, 1160 people have received the awareness level Language for Learning training – the majority from primary schools. 16 schools have had all their staff trained together. The training is now appearing on statements of special educational needs (SEN) as a strategy to support pupil progress. Identification and first-line support ‘Speechlink’ and ‘Language Link’, two screening packages for schools, originated in Kent. The County Council fund schools to use them. Speechlink is for children who have articulation problems and helps schools decide who needs to be referred for therapy. Language Link is used with a whole class (usually the Reception year group) and focuses on language comprehension. It takes in the order of 15 minutes per child. The class results are analysed by the provider company. Their report signposts children with more serious difficulties who should be referred to the SLT service, suggests wholeclass strategies, and provides programmes for individual children. Re-tests at the end of the year allow the school to evaluate the impact of the interventions. 3 70% of Kent primary schools use Language Link and work is underway to develop versions for Key Stage 2 and for secondary schools. Early years Kent has partnered with the charity ICAN to develop services in early years settings. In 2004, SLTs and specialist teachers in one part of the county became increasingly concerned about the number of children with severe SLCN requiring a place in a SLCN resource base, rather than attending their local primary school. There was also a recognition that offering a child a set of 45-minute SLT sessions, in isolation from the support that was being offered in the child’s nursery, was not going to significantly improve the child’s skills. It was decided that a joint approach was needed, which empowered parents to act as co-educators in the delivery of a therapy programme that could be delivered in a nursery, Children’s Centre or home. Local needs analysis showed that on average 10-12 children a year living in the area had severe SLCN and could benefit from an intensive specialist approach in the early years. To meet their needs, a multi-agency virtual team was established, consisting of a part time SLT (1.5 days a week); a full-time Learning Support Assistant; a Children’s Centre Teacher (0.5 days a week); an Early Years Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCO) (two days a week); and staff from a nursery based in a Children’s Centre. A referral pathway has been established which identifies the children who will benefit most from the service – children with specific language impairment rather than speech difficulties alone, or language delay. There is then a joint assessment by the SLT and Early Years SENCO. Targets are set in partnership with the parents. The child’s home nursery place is kept open and the child is offered a place for three mornings a week, over two terms, at a specific nursery linked to a Children’s Centre, where intensive intervention is offered. Parents receive regular support from the virtual team and a dedicated parents’ support group. Once the two terms are up, the child returns to his/her home nursery and the virtual team continues to offer the child and parent targeted support. This includes support in making the transition to the Reception class and follow-up support in the primary school until the end of Reception. The host Children’s Centre has developed a high level of expertise and become accredited at the specialist level of I CAN‘s Early Talk framework. Other Children’s Centres are likely to seek similar accreditation in future. Offering to keep the home nursery placement open for two terms, whilst also funding specialist nursery sessions, is an expensive option and may not be sustainable in the long term. So in another area of the county a peripatetic approach has been trialled. In this case the virtual team offers a joint specialist intervention in the child’s home and local nursery (one session in the child’s home and one session in the nursery for 12 weeks). Outcomes have been good and the local authority and PCTs are looking to roll out this model across the county, when resources permit. Other early years developments include the use of ICAN’s ‘Early Talk’ programme of training and accreditation of settings and services in targeted localities, Every Child a Talker in 20 settings, and the locally developed ‘SPARKLE’ programme. SPARKLE is targeted at settings where there is a child or children with significant special needs and disabilities and involves a multiagency team of SLT, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, advisory teacher and specialist learning support assistant. There is an initial observation of the child in the setting, joint identification of goals with setting staff, and a cycle of intervention and then review over a period of about eight months. The aim is to 4 develop the skills, knowledge and understanding of staff in the setting, so that staff are better able to support not only the target child, but children in future intakes. Secondary schools Some areas of the county do not have a resourced provision for secondary aged pupils with SLCN, leaving a potential gap in provision for children with persisting SLCN who have had intensive help in their primary years. Data confirmed the gap, showing that pupils who had been identified with SLCN as their primary need in primary years were ending up classified by their secondary schools as having behavioural, emotional and social difficulties. The PCT therefore invested in a new service to support these children. SLTs undertake transition work to prepare children for the Year 7 curriculum and the vocabulary they will need, and provide the secondary schools with a menu of support at universal, targeted and specialist levels. Universal Whole-school awareness raising training Teaching assistant training Lesson observation and feedback , providing generic advice to class teachers Targeted Intervention groups – Curriculum vocabulary for Y7, Small-group Narrative Skills, Lifeskills/interview skills for Y10/11, Talkabout for Teenagers (social and friendship skills) Basic screening to identify pupils with SLCN Specialist Individual assessment Individual language and communication support with teaching assistant present Student-focused whole- class participation plan Working memory CogMed programme Transition student groups Support for parents/carers Quality and productivity: Communication and Assistive Technology Joint funding from the NHS and Kent County Council has been used to set up a multiagency service which assesses and supports disabled children and young people who need assistive technology – voice output communication aids, devices that enable independent access to a computer for educational and social purposes, environmental controls that for example operate TVs, music systems and toys, or open doors. The service also provides training programmes for school staff, SLTs and other professionals. Working in partnership with families and professionals who support the child locally, three teams of SLTs, occupational therapists, therapy assistant practitioners, teachers and clinical technologists provide full-day multi-professional assessments. On the basis of these detailed assessments, communication aids and specialist computer equipment can be provided to the child on a long-term loan basis. The team implement a cycle of (at minimum) threemonthly visits to review the suitability of the devices provided, monitor progress against targets and set new ones. This ensures that ongoing training and support in using the technology is provided to users and the adults who live and work with them, and that expensive equipment is used to full effect or can be recycled and replaced with more suitable aids or software if it is not proving appropriate. 5 The service is provided in partnership between Kent County Council (education and children’s social services) and the NHS. The case for funding from the local authority was made on the basis of savings that would accrue as a result of educating children locally, rather than funding placements in independent and non-maintained special schools. Economic analysis has shown that good local services enabling just two children to remain in local provision will fund themselves; more children retained will result in overall cost savings for commissioners. An example of the benefits provided by the service is the case of one three-year old whose parents were advised that he had learning difficulties and would need to attend a special school. The assessment by the Communication and Assistive Technology Service team demonstrated that, at three, this child could read. He went on to mainstream school and is now on the school’s register of gifted and talented pupils. Quality and productivity: verbal dyspraxia Another example of effective use of evidence and cost-benefit analysis is the development of a specialist service for children with verbal dyspraxia (a neurological speech sound disorder). Until 2009, these children received a traditional package of weekly 30 minute clinic-based therapy sessions with a basic-grade SLT, in six-week blocks. Data indicated, however, that outcomes were poor. SLT managers drew on research showing that children with verbal dyspraxia do best with intensive support, and it was decided to trial a new way of working. Kent now has a service staffed by highly specialist SLTs, who assess children whose difficulties have persisted after one long block of at least 10 sessions of therapy in their local community clinic. The specialist SLTs see children in their local school or nursery setting, providing twice weekly therapy alongside parents and an identified member of the school staff, who are able to continue the therapy on a daily basis. The impact has been evaluated using the innovative East Kent Outcomes System (EKOS), a tool which allows aims and objectives to be set for episodes of therapy. This showed that therapy delivered in the new form was much more successful. Cost benefits were analysed, demonstrating for example that intervention for a child receiving the intensive service (28 previous clinic contacts until he was five, then 38 subsequent contacts with the specialist service, until he was discharged with age-appropriate speech at 5years 8 months) cost £1200, compared to £1350 for a child who had help on the previous model between the ages of 2 and 9, with little progress and ongoing therapy required. Impact The early years partnership work with ICAN has been evaluated. Evaluation has shown that, for the model of children attending the specialist centre for two terms: • 92% of the children supported were able to attend their local primary school and made good progress. Historically, children with similar needs would have needed to access a costly specialist language provision. • 70% of children demonstrated a marked increase in their understanding of language. • 80% of children showed an increase in their use of language. • Only one child out of 12 needed a statement of SEN. 6 • In some cases the child’s receptive and expressive language scores increased by such a large extent that they would no longer be classified as having a speech and language disorder. • Parental questionnaires returned evidenced a very high parental satisfaction rate for the service as a whole, and the support offered concerning the transition to Reception class. • All the children supported made progress above expectation. Improvement in their speech and language skills had a positive impact on the progress they made across other areas of the Early Years Foundation Stage Curriculum. The children showed greater self confidence and demonstrated reduced levels of frustration when interacting with others. • Home nurseries reported an increase in their knowledge base in supporting children with severe speech, language and communication impairments. The peripatetic service was also highly successful: • 90% of the children supported were able to attend their local primary school. • 33% did not need any further intervention after six months, and the others demonstrated marked improvements in their use of language and understanding of language. • The intensive intervention model led to an increase in parent’s confidence in meeting their child’s SLCN. Next steps Next steps for Kent are to develop a truly integrated local authority/health commissioning framework for SLCN. The SLCN steering group has used consultancy from an experienced SLT manager from another area to help them review existing provision and develop the strategy that will drive the planned integrated local authority/health commissioning framework for SLCN. Parents were also brought into the review process. So far, the review has identified a requirement for a more extensive needs analysis, the development of measurable outcomes for services, and work on mapping the whole system – not just SLT services. It has also identified a number of priorities: More work on teacher training, including work with Canterbury Christchurch University on how coverage of SLCN within initial teacher training might be improved, Increased involvement of School Improvement Partners, Rolling out Every Child a Talker across the county, Developing further services for secondary schools, and Developing work with the Youth Offending Service. November 2010 7