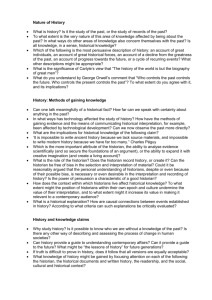

Writing Historiography Essays

advertisement

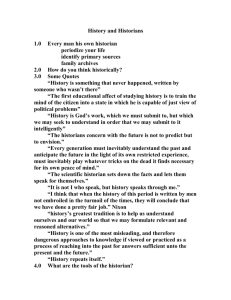

WRITING HISTORIOGRAPHY ESSAYS IN HISTORY EXTENSION Here is a sample question that follows the format of Section 1 in your HSC: Section I 25 marks Attempt Question 1 Allow about 1 hour for this section In your answer you will be assessed on how well you: present a detailed, logical and well-structured answer to the question use relevant issues of historiography use relevant sources to support your argument Using the Source, answer the question that follows. Source History is always an attempt to explain the sequence and connection of events, to explain why, after the events of 1789, there followed the Revolutionary Wars, the execution of the King, the Jacobin dictatorship, the Terror and the Thermidorian Reaction. Not why they had to follow — that is prediction in reverse, and the historian has no business with prediction—but why in fact they followed. Now, the moment the historian begins to explain, he is bound to make use of general propositions of all kinds — about human behaviour, about the effect of economic factors and the influence of ideas and a hundred other things; It is impossible for the historian to banish such general propositions; they are smuggled in by the back door, even when he refuses to admit it. He cannot begin to think or explain events without the help of the preconceptions, the assumptions, the generalization of experience which he brings with him — and is bound to bring with him — to his work. When Mathiez for example began to work on the history of the French Revolution, his mind was not a blank, it was full of views and prejudices about revolutions and their causes, about the way people behave in times of revolution, about how much importance to attach to economic, how much to intellectual factors. The historian gives a false account of his activity if he tries to deny the part a general ideas and assumptions play in his work. In such work it is obvious that the first rule of the historian must be to keep a critical eye on his own assumptions and pre-conceptions, lest these should lead him to miss the importance of some piece of evidence, the existence of some connection. His whole training teaches him to break down rather than build up generalizations, to bring the general always to the touchstone of particular, concrete instances. His experience of this discipline and its results makes him cautious and sceptical about the possibility of establishing uniformities and regularities of sufficient generality to bear the weight of the conclusions then built up on them. Probabilities, yes — rules of thumb, the sort of thing you can expect to happen—but not more than this... Bullock, A. (1959), The Historian’s Purpose Now, the moment the historian begins to explain, he is bound to make use of general propositions of all kinds — about human behaviour, about the effect of economic factors and the influence of ideas and a hundred other things; It is impossible for the historian to banish such general propositions; they are smuggled in by the back door, even when he refuses to admit it. He cannot begin to think or explain events without the help of the preconceptions, the assumptions, the generalization of experience which he brings with him — and is bound to bring with him — to his work. When Mathiez for example began to work on the history of the French Revolution, his mind was not a blank, it was full of views and prejudices about revolutions and their causes, about the way people behave in times of revolution, about how much importance to attach to economic, how much to intellectual factors. The historian gives a false account of his activity if he tries to deny the part a general ideas and assumptions play in his work. In such work it is obvious that the first rule of the historian must be to keep a critical eye on his own assumptions and pre-conceptions, lest these should lead him to miss the importance of some piece of evidence, the existence of some connection. His whole training teaches him to break down rather than build up generalizations, to bring the general always to the touchstone of particular, concrete instances. His experience of this discipline and its results makes him cautious and sceptical about the possibility of establishing uniformities and regularities of sufficient generality to bear the weight of the conclusions then built up on them. Probabilities, yes — rules of thumb, the sort of thing you can expect to happen—but not more than this... Bullock, A. (1959), The Historian’s Purpose Question 1 (25 marks) Evaluate Bullock’s view of the role of the historian, referring to at least two other sources you have studied. So...... how do I go about answering this? Step 1: Identify exactly what the question is asking me to do. I need to focus on what Bullock says about the role of the historian. The question uses the term ‘evaluate’, so I need to build an argument in which I assess the strengths and weaknesses of Bullock’s view. I need to compare and contrast Bullock’s views with those of at least two other historians. Step 2: Identify the main ideas in the source. Important quotes: ‘History is always an attempt to explain the sequence and connection of events’ ‘It is impossible for the historian to banish such general propositions; they are smuggled in by the back door, even when he refuses to admit it.’ ‘In such work it is obvious that the first rule of the historian must be to keep a critical eye on his own assumptions and pre-conceptions, lest these should lead him to miss the importance of some piece of evidence, the existence of some connection.’ Bullock thinks the role of the historian is to explain causation in history. The historian needs to be able to use the evidence to construct a narrative that explains why events occur in the way that they do. While writing such narratives, the historian will inevitably be influenced by their own perspective and presuppositions. However, thanks to the historian’s professional training, they are able to keep their presuppositions under control, and to make sure that they remain governed by the evidence, not their presuppositions. Bullock therefore appears to be expressing a basically positivist view. The past is there to be discovered in the traces of evidence that survive. This past can be accessed by the historian using their professional training to keep their own perspectives etc under control. Bullock’s view also reflects the focus of ‘traditional’ history in that he appears to be interested in the causes of big political events, rather than in ‘history from below’. Step 3: Decide which other sources to use. To help contextualise Bullock’s views, I will refer to Ranke, Acton and Windschuttle. I will use Carr to critique Bullock’s attitude towards historical evidence. I will use Jenkins (and to a lesser extent Foucault) to critique Bullock’s attitude towards the professional role of the historian. Step 4: Plan and Write your Essay. Intro: Bullock’s faith in the ability of historians to rise above their own presuppositions is rendered untenable by the post-modern critique. While acknowledging the impact of historians’ perspective on the narratives they write, Bullock expresses a positivist’s trust in the essential certainty of historical evidence. However, as Carr points out, historical evidence does not provide an unassailable foundation for the historian’s interpretation, but is itself a product of the historian’s perspective. Furthermore, the professional training of the historian does not, as Bullock suggests, guard against the intrusion of their perspective. Rather, as Jenkins argues, it makes up part of the ‘frame’ that shapes how the historian conceptualises and undertakes their task. Paragraph 1: According to Bullock, the role of the historian is to explain historical events by constructing narratives based upon rigorous attention to historical evidence. Not simplistic like Windschuttle or Elton in thinking the facts ‘speak for themselves’. Facts need a narrative for them to make sense – he refers to the role of the historian in seeking to ‘explain the sequence and connection of events’. He sees that this explanation will be influenced by the historian’s perspective. But Bullock thinks that professional training and proper methodology will allow the historian to keep a proper focus on the evidence, implicitly allowing them to write a reliable account. Paragraph 2: Despite acknowledging the influence of the historian’s perspective on their work, Bullock’s views place him firmly within the tradition of what Burke calls ‘old history’. Subject matter is traditional – focus on explaining ‘historical events’, in contrast to history ‘from the bottom up’, for example (give an example of a different historian). He acknowledges the influence of the historian’s perspective on their interpretations, but treats the historical evidence as something solid and reliable – a trustworthy foundation for the historian’s work. He reflects the tradition established by Ranke of history as an academic discipline, with specialised methodologies. Paragraph 3: As Carr has demonstrated, Bullock’s positivist attitude towards historical evidence is problematic. Bullock thinks historian’s perspective only influences their interpretation of evidence. Carr argues that perspective of historian determines why some traces of the past are identified as ‘historical facts’ while others aren’t: ‘It is the historian who has decided for his own reasons that Caesar’s crossing of that petty stream, the Rubicon, is a fact of history, whereas the crossing of the Rubicon by millions of other people before or since interests nobody at all.’ (Carr, 1961) Carr therefore places greater emphasis on the historian’s role in ‘creating’ historical ‘truth’ than Bullock does. He comes close to postmodern historiography in suggesting that constructions of the past are always going to be contingent and fluid: ‘My first answer therefore to the question “What is history?” is that it is a continuous process of interaction between the historian and his facts, an unending dialogue between the present and the past.’ (Carr, 1961) Paragraph 4: Although Carr’s critique of Bullock’s approach exposes the weakness of positivist attitudes towards evidence, it does not go far enough. Bullock sees the goal of historical writing to explain events, construct narratives. Carr expresses even more of a modernist point of view by claiming that interpretations of the past are shaped by the historian’s view of the future (!): ‘The absolute in history is not something in the past from which we start; it is not something in the present, since all present thinking is necessarily relative. It is something still incomplete and in process of becoming – something in the future towards which we move, which begins to take shape only as we move towards it, and in the light of which, as we move forward, we gradually shape our interpretation of the past.’ (Carr, 1961) I think this reflects Carr’s Marxist intellectual influences. In contrast, this belief in teleological meta-narratives is rejected by postmodernist thinkers such as Foucault and Jenkins. Paragraph 5: Foucault and Jenkins also convincingly undermine Bullock’s reliance on historical methodology. Bullock – proper training allows historian to take their perspective into account. Jenkins attacks this by arguing that the professional context of the historian is not something that guarantees objectivity, but prevents it: ‘History is arguably a verbal artifact, a narrative prose discourse of which, apres White, the content is as much invented as found, and which is constructed by present-minded, ideologically positioned workers...’ (Jenkins, 1995) Foucault goes even further by pointing out that the construction of all knowledge within a society is a product of power relations within that society. It is therefore impossible for a historian to ‘rise above’ their context by some methodology: the methodology is part of that context. (Expand). Conclusion Postscript.... ... just in case you think this is all too ‘pro-po-mo’: ‘But postmodernism is itself one group of theories among many, and as contestable as all the rest. For my own part, I remain optimistic that objective historical knowledge is both desirable and attainable. So when Patrick Joyce tells us that social history is dead, and Elizabeth Deeds Ermarth declares that time is a fictional construct, and Roland Barthes announces that all the world’s a text, and Hans Kellner wants historians to stop behaving as if we were researching into things that actually happened, and Diane Purkiss says that we should just tell stories without bothering whether or not they are true, and Frank Ankersmit swears that we can never know anything at all about the past so we might as well confine ourselves to studying other historians, and Keith Jenkins proclaims that all history is just naked ideology designed to get historians power and money in big university institutions run by the bourgeoisie, I will look humbly at the past and say despite them all: it really happened, and we really can, if we are very scrupulous and careful and selfcritical, find out how it happened and reach some tenable though always less than final conclusions about what it all meant.’ Richard Evans (1997)