Although the title of Barry Fell`s seminal work, America B

advertisement

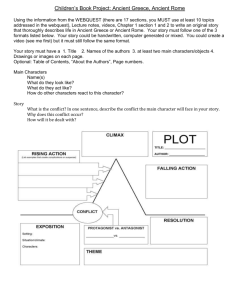

1 Ancient Visitors and Settlers in the Americas A Commentary on Barry Fell’s America B.C. By Neil DeRosa America before the Common Era? Have the American continents been explored and even settled by Europeans long before Columbus or Leif Erickson ever set foot on these shores? If so, then our knowledge of ancient history is ruefully lacking—especially of our own American history. One scientist, a world authority on many of the dead languages of the Bronze Age, thinks so. Although the title of Harvard professor Barry Fell’s Bicentennial book, is America B.C., the ”B.C.” can be equally interpreted as “before Columbus” or “before Christ,” but the latter seems more appropriate since most of the facts brought to light as a result of his researches apply to the earlier time frame. This well-known epigrapher is the principal scientist of the current paradigm challenge under discussion. His theory is applicable to our ongoing theme that one highly qualified individual in a particular field or discipline employing well substantiated evidence and a careful scientific approach, can present an impeccable case for an extraordinary hypothesis that should be taken seriously by mainstream science—but normally isn’t. This article does not dispute the credible evidence that other, non western peoples, especially the Chinese, have explored and influenced the Americas before Columbus’ arrival; but since Fell’s 1976 work does not deal with this issue, it is not included in this article. History begins wherever we find the written word; and here in America, if you know what to look for, there is an abundant record written in stone, dating from the millennium before the Common Era. But the stone inscriptions that Fell uses as evidence are scoffed at by institutional archeologists, if not as outright forgeries, then as “marks made by farmers’ plowshares,” or “scratches made by Indians sharpening their spears,” or “drill marks made by colonial stonecutters.” These inscriptions however, are often identical in shape, size, location, and scientific dating to known inscriptions in stone found in Europe and other places. There they are recognized by scholars as written words carved out in Ogam, the alphabet of the ancient Celts, or in any one of several other Bronze Age alphabets and languages such as Libyan, Egyptian, Punic, Iberian, and Basque. Various standard dating methods of these artifacts indicate extreme antiquity. Moreover, the monuments, bronze implements, the pottery shards, and other art relics found in conjunction with these inscriptions are known to be associated with these same cultures and peoples. Here then is another extraordinary, but most likely true hypothesis being relegated to subjectivity. Why? Because the evidence is discarded with the explanation that it is not what it appears to be. This evidence has been gathering piecemeal since colonial times, but until recently most scholars did not know how to interpret it. Now that they do (or should) know, as several ancient languages and their alphabets have since been deciphered, mainstream science still refuses to take it seriously; thus reinforcing our ongoing theme that there is something wrong with science. This theory, along with other credible theories already discussed, must be entered into in the record of Apocryphal 2 science for future reference. Perhaps more generations will pass before the opportunities missed to add to our knowledge of the world around us will be recognized. The Lapidary Record and an Oral Tradition “The men of Tarshish established colonies in eastern North America, the settlers drawn from the native Iberians (that is Celts and Basques) of the Guadalquivir valley in Andalusia.” The most advanced culture in Spain at the time was Phoenician (or Punic). The Phoenicians were world famous traders and seamen in the ancient world. Tarshish, one of their major cities, was well known in antiquity for its great ships. “The first authenticated find of an engraved Phoenician tablet in an American context was that of a Tartessian inscription found in 1838. This tablet was excavated from a burial chamber found at the base of Mammoth Mound, in Moundsville West Virginia.” Although the inscriptions could not yet be deciphered, scholars recognized by its similarity to Iberian writing that it must be of European origin. The idea that Europeans had visited and settled North America in ancient times was an acceptable scientific hypothesis until around 1870, at which time the opinion became widespread that no such visitors or settlers had arrived before Columbus, and Moundsville was forgotten. (157; all page references are to America B.C. Artesian Publishers reprint.) The Moundsville tablet was thereafter considered to be a recent Cherokee artifact or a fake, and the mounds themselves, the product of Woodland Indian culture, notwithstanding that they were similar to those found in Portugal. Other early efforts to identify the tablet were spurious and further discredited epigraphy in America. Interest in the Tartessian inscription was renewed in 1974 by Professor G. Carter who noticed similarities to Libyan Inscriptions deciphered by Fell elsewhere. (163) Fell was familiar with the style of ancient Semitic writing without vowels and written from right to left, and he made rapid progress. He translated the tablet to read: The memorial of Teth / This tile / His brother caused to be made. (158) During the 1940s Dr. W. Strong collected hundreds of inscribed stones from the Susquehanna Valley. They were found by Fell to be of ancient Basque, Celtic and Punic origins, grave markers from a Bronze Age settlement of 800-600 B.C. (170) In 1901-02, F. Russell, of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology, translated an ancient Creation Chant of the Pima Indians of the Southwest. Although his effort was respectable, he failed, according to Fell, to recognize the chant as an ancient Semitic hymn. Russell’s translation, which renders the Chant childlike and nonsensical, is on file in the Bureau’s archives. When Fell translated the Chant using a Semitic dictionary, the result was “a conception of the Creation as logical as any found in ancient scripture,” (171) even including a “flood myth” familiar to many from Biblical and Sumerian writings. The first two stanzas Fell’s translation of this oral tradition Chant read: In the beginning the world-magician created the earth. As time went by he set plants upon his handiwork. 3 The Pontotoc stele, discovered or brought to light by field archeologist G. Farley, “found in Oklahoma, is apparently the work of early Iberian colonists in America,” and is dated ~800 B.C. The inscribed words found on the stele identify them as extracts from the known (to Egyptologists) Hymn to the Aton, by Pharaoh Akhenaton (circa 1300 B.C.). (159) Part of the stele reads: “When Baal-Ra rises in the east, the beasts are content, and when he hides his face, they are displeased.” The Davenport Calendar stele, found in a burial mound in Iowa in 1874, by Rev. M. Gass, is a petroglyph comprised of a scene depicting a group of worshipers holding hands and gathered around a ceremonial object—a kind of maypole—with a rendition of the sun and stars, a “mirror,” and strange writing. It is now known to be inscribed in three languages: Egyptian hieroglyphics, Iberian-Punic, and Libyan. The Egyptian writing could have been deciphered at the time of its discovery but wasn’t. The stele was condemned as a meaningless forgery by mainstream scientists from Harvard and the Smithsonian on the grounds that they could not read the inscriptions. Because of poor scholarship a national treasure and priceless artifact might have been lost; but luckily that didn’t happen. In fact, this is one of the most important steles ever discovered because it is the only one on which is inscribed related messages in a tri-lingual text of known languages. It is kept in the Putnam Museum in Davenport, Iowa. (261) Fell’s translation of the three languages follows: The Libyan reads: This stone is inscribed with a record / It reveals the naming, the length, (and) the placing of the seasons. The Punic-Iberian reads: Set out around this is a secret sign/text defining the seasons delimiting. Neither the Libyan nor the Punic-Iberian scripts had been deciphered when the stele was discovered in 1874, yet both yield mutually consistent readings which can be confirmed by other competent epigraphers. This constitutes a priori verification of their authenticity. The Egyptian Hieroglyphics found on the Davenport stele, written in the informal or Hieratic style (as opposed to the formal Temple style), reads as follows: To a pillar attach a mirror so that when the sun rises on New Year’s day it will cast a reflection on the stone called The Watcher. New Year’s day occurs when the sun is in conjunction with the constellation Aries in the House of the Ram, the balance of the night and the day being about to reverse. At this time (the spring equinox) hold the festival of the New Year, and the religious rite of the New Year. (265) 4 This translation can also be confirmed by other epigraphers. In another line of evidence it can be shown that the Davenport stele is an example of the known Djed Festival of Osiris, an Egyptian rite discovered by A. Erman from a tomb inscription of the XVIII Dynasty in Thebes, Egypt. The Djed Festival is one and the same as that depicted and described on the Davenport Stele found in Iowa. The Orient Point stele, discovered in 1888 in a shell bed on the eastern tip of Long Island, NY, now sits in the Museum of the American Indian in New York. No one questions its authenticity; it is simply considered to be an example of Amerindian rock art, depicting a hunt. In fact it is inscribed in two languages, Egyptian and Libyan. The stele, which dates from ~ 900 B.C., could not have been forged since the Libyan alphabet was not deciphered until 1973. (270) Though Fell concedes that this may be an Algonquian copy of the original, since some of the symbols coincide with Micmac, a related tribe to the Algonquian, who Fell believes learned hieroglyphics from the ancient Egyptians. The Egyptian script reads: A ship’s crew from Upper Egypt made this stele with respect to their expedition. The Libyan text reads: This ship is a vessel from the Egyptian dominions. Many inscriptions found in Ogam in the New England area and elsewhere are cited by Fell. Some examples are as follows: An Ogam inscription found near South Woodstock Vermont reads: The precincts of the Gods of Iargalon. (240) Another is on a tomb marker nearby that reads: Lugh son of Valiant. (60) A stone chamber near South Royalton Vermont disclosed two Ogam inscriptions. The entrance lintel reads: Temple of Bel. Fell’s translation of an inscription inside the chamber reads: Pay heed to Bel, his eye is the sun. Epigraphy After these introductory examples and remarks on some of the least ambiguous evidence we have, the reader is probably wondering by what authority Fell is making his claims. What allows him to render the translations and interpretations he makes? Fell devotes considerable space in America B.C., and also in Bronze Age America and in numerous other articles and scholarly publications in making his case. Our task here is to demonstrate if possible how Fell’s work is consistent with the science of epigraphy and also with archeology, as it was originally understood; that is, as a science which studies ancient manuscripts and inscriptions. A brief recounting of the history of epigraphy follows: During the 12th Century A.D. Irish monks continued the work of many centuries of preserving the knowledge of the ancient classical civilizations. One beautiful work written by them at that time was the Book of Ballymote, which contained numerous ancient alphabets; “alphabets galore,” as the Irish say. One part of the book, derived from an even earlier manuscript, is called the “Ogam Tract” because it contains some seventy varieties of Ogam, the ancient script of the Irish. (28) Modern linguists and epigraphers 5 ridiculed this work when it first became known to them, considering it the childish meanderings of secluded monks with nothing better to do. Eventually as more evidence came in from field archeologists, “Line 16” of the alphabet list was recognized as the variety of Ogam that had been recently discovered in lapidary writing inscribed on ancient monuments in the British Isles. (47) Ogam was thereafter recognized as the ancient alphabet of the Celts who had come from Iberia to settle Britain, finally migrating to Ireland and Scotland after they had been driven out of England by the Gauls. But if these Irish and Scottish Celts had ancient roots in Iberia, perhaps their written alphabet had also. Besides “Line 16” of the Ogam Tract, which became the model for the recognized “grooved writing” or “finger writing” of the ancient Celts in Britain, Scotland, and Ireland; the Tract also contained, in Lines 1 - 15, several earlier versions of Ogam not yet recognized by epigraphers and archeologists of the day (indeed, they are not recognized to this day). The Book of Ballymote also contained the ancient alphabets of Punic, Iberian, Phoenician, Libyan, and Egyptian scripts; (58) many of which could not be read or understood until modern epigraphers later deciphered them, beginning with Champollion’s famous deciphering of the Rosetta Stone under Napoleon’s decree. But the honor of being the first scientist to decipher an ancient inscription in stone goes to Charles Vallancey, who in 1784 predicted the location of, and deciphered, the tombstone of an ancient Celtic hero named Conan Colgac, who as legend had it was killed in battle and buried on a certain mountain top in Ireland in 283 A.D. (31) Vallancey sent a field assistant named O’Flannagan to climb the mountain to see if there indeed existed the inscribed ancient tomb of Conan Colgac. O’Flannagan found the tomb and inscription, whereupon Vallancey deciphered it using Line 16 of the Ogam Tract, which was variously translated in several versions since then. Thus began the history of epigraphy, but not without the usual incriminations and accusations of fraud. It has not yet been mentioned that the many varieties of Ogam in the alphabet list were accompanied by line-by-line translations into Gaelic, the language of Ireland, and written in the well-known Romanesque or Gothic alphabet. The Gaelic translation of Line 16, (and also of the other alphabets of the Tract), was the key to the new science of epigraphy. This key also seems to have been independently discovered by Champollion in his deciphering of the Rosetta Stone, on which the Egyptian hieroglyphics were juxtaposed line-by-line with an accompanying translation in ancient Greek, a known language. This ingenious but simple method of Vallancey and Champollion bears mention here because it is the key that unlocked the door to all future epigraphy, and the deciphering of ancient languages and alphabets in general—including Fell’s deciphering of the ancient inscriptions found in America, which by a consistent application of the same principle, must be credible. Lines 1 – 15 of the Ogam Tract, which included the most ancient forms of Iberian Ogam, remained a mystery because out of some 400 known inscriptions in Great Briton, no examples of it were found. Lines 1 - 15 were still considered to be mere monkish shenanigans; special codes used among the monks the way “pig Latin” is used by 6 children today, not real alphabets representing real languages. But eventually many of these alphabets too were deciphered by Fell, and confirmed by other epigraphers with similar discoveries of inscriptions with similar dating in the Iberian Peninsula. The work is still ongoing. One interesting and ironic twist in this saga is that much of the field evidence and examples of these ancient languages and alphabets, dating from the first millennia B.C. and before, was found not in Europe, but in the Americas, because the inscriptions had not been erased as “pagan writing” by the over-enthusiastic early Christians of Europe. They were found where no European was ever supposed to have gone before Columbus or Leif Erickson. The New England Celts Before 467 A.D. when “the lamps went out all over Europe,” which was of course the year Rome fell, the memory of a “land beyond the sunset,” Iarghal or Iargalon, survived among Irish scholars. (45) But gradually over the centuries that followed that memory faded, and by 1492 it was all but forgotten. Nevertheless it had happened that the Celts and other peoples of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East had crossed the Atlantic and had visited or settled those shores many times over thousands of years. The Celts favored New England, perhaps because it reminded them of their homeland. The New England Celts employed an Ogam alphabet of at least 12 letters without vowels, the same as that used in Spain and Portugal of the time (~800 B.C). For those willing to attribute to coincidence anything that doesn’t fit into their preconceived biases, consider the unimaginable odds against identical alphabets in two separate places arising by chance. In other words, the people who made the inscriptions in Iberia were the same people and culture as those who made them in New England. (193) Julius Caesar wrote an account of the Celts after his invasion of Briton in 55 B.C. He noted their considerable knowledge of the stars and of their motions, and of the dimensions of the earth. He also noted their great ships, (to be discussed in the next section). The scientists and teachers of the Celts, in those days thought to be magicians, were called Druids. (195) The monuments built or used by the Druids, such as the famous Stonehenge in England, are proven by modern studies of them to have been astronomical observatories, made by a people with advanced scientific knowledge and engineering skills. (196) Fantastic though it may seem, similar monuments were also built in New England in the millennium before the Common Era. One of the most important findings of (Fell’s) work in Vermont has been the demonstration that certain megalithic monuments are related to astronomical functions of a like nature to those in Briton and other parts of Europe, and that some of them carry Celtic inscriptions referring to their astronomical functions. (196) But it was the solstice monuments first discovered by R. Stone at Mystery Hill in North Salem, New Hampshire that are the most impressive. Before 1965, it was not known that an ancient astronomical observatory built 3000 years ago had existed there. This discovery was the first clear indication that the ruins of Mystery Hill were the work of people who regulated their calendar in the same way as the builders of the megaliths of Europe. (205) The Celts used the calendar attributed to the Greek philosopher 7 Hippocrates, but is perhaps much older. This “Hippocratic” calendar year begins on the day of the spring equinox in March (when the sun is directly over the equator); the next important date is the summer solstice when the sun reaches its furthest northern declination of 23.5°; next is the autumn equinox in September; and then the winter solstice of -23.5° south azimuth (when the sun is in declension at its furthest angle to the south of the equator). That the ancient Celts of New England had this knowledge is evident in the many monuments and inscriptions discovered by Fell and his associates. These include a calendar circle at Mystery hill in which azimuth angles related to these seasonal dates can be shown to coincide with several standing marker stones seen from an observation platform, with the mean deviation from the calculated angles being only minutes of an arc. (206) These calendar sites were designed so that certain marker stones, notches or excrescences would be identified as places where the sun would rise or set on key dates, when viewed from a specified observation platform or position. For a year that begins with the spring equinox there is a stone to mark the position of sunrise or sunset, another stone for Beltane on May 1st, another marking the June solstice, and so on. (215) To accomplish this feat of engineering, the Druids would obviously have to be able to predict in advance the position of the sun on these dates in order to set the markers or build their monuments accurately. They would also have to be able to determine true north. All of this presupposes that a sophisticated knowledge of astronomy existed in New England, 3000 years ago. Mysterious “root cellars” have been known to exist in New York and New England since colonial times. But they were not built by the early colonials who themselves found them here when they arrived. Neither were they built by the American Indians who denied building them, and who could not have made the Ogam inscriptions found in many of them nor have made the astronomical calculations. Neither were the structures constructed as root cellars. Most were temples to the Celtic god Bel, who was probably the same personage as the Semitic god Baal. They were also used as calendar regulators, which is the same thing as saying that they heralded the arrival of important religious festivals, such as Beltane on the first day of summer, dedicated to the sun god Bel. (209) They were built to the same precise specifications as the calendar regulating structures described above. As pertains to the stone buildings, Fell collaborator B. Dix comments: The building of so many substantial stone buildings (over 200 are now on record) shows that the work was done by permanent colonists from Europe, and that New England was occupied by Celts as early as the first millennium B.C. Reiterated claims that the buildings are “root cellars” made by colonial farmers during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries must be dismissed, though it is true that some of the stone buildings were converted to mundane uses by those settlers who discovered them on their property. (214) The advanced understanding of astronomy and other sciences, and the ability to put that knowledge to use in the construction of buildings, megaliths, dolmans, and monuments often used to regulate the calendar, implies that they also had the ability to navigate 8 accurately by the stars and the position of the sun. They even possessed navigational instruments, as we shall see. Many other examples of these structures are described by Fell, and can be found in the References section. Bronze Age Navigation Although the exact location of the ancient city of Tarshish is not settled science among historians, Fell maintains that Spanish archeologists are fairly certain that it was in southwestern Spain; and also that the Tartessians used a distinctive variant of the Phoenician alphabet. (93) From the Bible we learn that the ships of Tarshish were the largest known to the Semitic world of ancient times, and are referred to in several places in the Old Testament. The merchants of Tarshish were renowned for their transport of riches and precious commodities to all parts of the ancient world. These facts are also corroborated by Spanish archeologists. The Celts, who moved down from the North in large numbers were in intimate contact with the Tartessian and Phoenician cultures, and must have learned the art of shipbuilding from them. (94) It is not unlikely, given Fell’s evidence, that these different cultures cooperated in voyages to America in order to mine precious metals and engage in the fur trade. (94) One inscription, called the Bourne stone, recorded the annexation of the Massachusetts area by the Punic king Hanno. (95) An inscription found in Paraguay reads: Inscription cut by Mariners from Cadiz exploring. (98) One found at Mount Hope, Rhode Island reads: Mariners of Tarshish this rock proclaims. (99) An inscription in Ogam found on Manana Island, off the coast of Maine reads: Ships from Phoenicia, cargo platform. An Ogam inscription found in Saint Vincent Island in the West Indies, dated ~800 B.C. reads: Mabo discovered this remote western isle. (115) A long and detailed inscription in Phoenician script found in Parayyba, Brazil in 1886, now lost, reads in the first two lines: This monument has been cut by the Canaanites [i.e. Phoenicians] of Sidon who, in order to establish trading stations in distant lands…set out on a voyage in the nineteenth year of the reign of Hiram [i.e. 536 B.C.]. (111) It is now a well established scientific fact that late Bronze Age sea-going commerce was well developed and highly organized by at least 500 B.C. This is not disputed; what is disputed is of course that such commerce ever extended to the Americas. For example, a letter was excavated in Pergi, Italy and written on gold-leaf. “This letter (written in Etruscan, which Fell deciphered) deals with a shipment made from Tyre to Italy, and shows that extremely valuable cargoes were entrusted to the Tyrian vessels, is this case almost certainly one of the ocean-going Tarshish class.” (102) The letter is in effect a detailed contract, with several references to the local and national gods of the parties involved in the transaction. The counter argument is that all of the good evidence is found in Europe, and this does not prove that it applies to any oceanic travel outside of the Mediterranean Sea. But there are also well documented records of early voyages across open oceans. In 140 B.C. during the Han Dynasty, the emperor of China commissioned ocean voyages spanning thousands of miles reaching southern India, with subsequent trade routes being established between the Chinese, Indian, and Arab civilizations. Greek shippers had long 9 established trade routes to India; and in 30 A.D., using the monsoon winds crossed the Indian ocean. Upwards of 100 ships set out for India each year to pursue the lucrative commodities trade in silks, spices, and gems in exchange for Roman gold. There is little doubt that these were sailing ships exploiting the monsoon winds, and not galley ships with crews of rowers. (109) Contrary to folklore, the ancients did not think the earth was “flat;” in fact the Greek philosopher Eratosthenes had calculated the circumference of the world in 239 B.C. as being about 28,000 miles, an error of only ~13%. Longitude was set by dead reckoning, that is, by the sun, moon, and stars; and “the astronomical observations were set into an early type of astrolabe which combined with the cross staff for measuring the elevation of the midday sun…at the time of their meridional passage, yielded a direct reading of latitude.” (110) Other mechanical instruments discovered by archeologists, for calculating the time of day, the position of the stars, for converting angles from polar to elliptical coordinates, and so on; were invented in ancient Libya and ancient Greece. (120) It is a mistake to think that the “age of navigation” began only with Vasco da Gama, Diaz, and Columbus. (110) Columbus’ expedition in 1492 amounted to 88 men in 3 small ships, two of which were only 50 feet in length. The ships of the ancient world were often considerably larger and surprisingly well built. As mentioned above, no less an authority than Julius Caesar attested to the great size and seaworthiness of Celtic ships. (113) In the battle of Britain in 55 B.C. the combined Celtic forces placed a fleet of 220 sailing ships against Rome, ships that could even sail into the wind. But they lost to the disciplined Roman army, who threw grappling hooks from their galleys when the wind died. (116) The well designed Celtic ships had hulls which were held together with heavy beams bound with iron chains; they also used iron anchors. (117) A sunken Celtic ship discovered by Dr. Margaret Rule off the coast of Guernsey, (in the English Channel) demonstrated the truth of Caesar’s words. It had timbers made of oak beams two feet thick. (124) But just as Rome had earlier destroyed the sea power of Carthage (the capital city of the Phoenician civilization), in 149 B.C., it is clear that Rome broke the power of Celtic Navigation, although there is some evidence that under the Romans, Celtic voyages continued for some time. (200) Evaluation – Pros and Cons There are several possible reasons why Bronze Age exploration of the Americas is not in the written record that has come down to us from classical civilization. One obvious reason is that the “Dark Ages” following the fall of Rome in 467 A.D. really were in many respects dark. Tribal warfare erupted, lines of communication broke down, and centers of learning were destroyed. It took Europe hundreds of years to recover from this collapse. It would be a mistake to say that the ensuing “age of religion” was completely detrimental to learning and the preservation of classical civilization. The example of the Irish monks given above is certainly one example where this was not so; and there are others. Still there were many cases where religious intolerance and suppression had a 10 chilling effect on learning and the preservation of ancient knowledge. The burning of the famous library of Alexandria is an oft quoted example. Another reason there is no ready memory of ancient voyages to America is that written language during the bronze age was still essentially in its infancy. Most writing was done, and only rarely, on stone or clay tablets, with gold leaf later coming into play, and for obvious reasons only for the very wealthy. Another reason is time. Perhaps a thousand years went by between the heyday of the Classical Age and the Renaissance when interest in knowledge and discovery were again renewed. During that length of time, it is not surprising that historical facts and oral traditions could be forgotten, besides which, the earth’s whether cycles tend to bury old evidence under layers of sediment. Archeologists must dig it up; it is not an easy process. So it is not surprising for new generations to forget the knowledge of the past. What is surprising to this writer is the tendency of today’s science establishment to resist new ideas and new discoveries, in patterns that often seem to repeat themselves. The good evidence found in America, inscribed in stone, is dismissed automatically because it would require a paradigm shift to accept it. And those are presently out of fashion. On the negative side; it is true that science must proceed cautiously. Archeological finds must be provenienced carefully to assure against fraud and mistakes. Translations must be corroborated by other epigraphers who are qualified to make the attempt. And new hypotheses must not claim more than they are entitled to claim. In a work of this type it would be inappropriate for this writer to draw any final conclusions, except to say that based on patterns we’ve seen before, and based on what seems to be the ubiquity of Kuhn’s Law, we find Barry Fell’s case to be compelling, though much more research is needed. The Method of the Detractors One other reason this writer tends to lean toward the validity of Fell’s thesis is observation of the methods of detractors, a phenomenon we’ve noted before. A certain method of argument is used when the paradigm challenger’s case is strong. The key to this method is to attack the weakest points, (in this case of Barry Fell’s argument), and to ignore all of the good evidence. If the good evidence is critiqued, it will necessarily have to be misrepresented. A case in point is a short article by W. Hunter Lesser, entitled “How Science Works And How It Doesn't,” published in The West Virginia Archeologist Volume 41, Number 1, Spring 1989. The article is critical of Fell’s decipherment of an petroglyph found in West Virginia and reported on by Fell in an article in 1983 entitled, “Christian Messages in Old Irish Script Deciphered from Rock Carvings in W. Va.,” (Wonderful West Virginia 47(l): 12-19). Lesser begins with a veiled ad hominem attack on Fell’s credibility as a scientist by giving a primer for beginners on the scientific method and by listing typical techniques of a bad scientist. He also states explicitly that Fell is working in a vacuum, that is, without support or feedback from his peers. This is all absurd on the face of it since Fell is a world renowned epigrapher with innumerable credible publications and 11 contributions to the field; he is the founder of the Epigraphic Society, and has had numerous collaborators and supporters in his work over the years. As the point of the Lesser article was to discredit the earlier Fell article, we leave our reportage there since Lesser makes no comments on the actual article. Another website, Straight Talk about God, engages in more abuse and ridicule of another decipherment of Fell supposedly inscribed in ancient Hebrew, of the Ten Commandments, called the Las Lunas Decalogue, an apparent forgery made by Mormons. Other critics have ridiculed Fell’s contention that the Irish monks have visited America during pre-Columbian, Christian times. No one can reasonably argue that any scientist dealing in cutting edge, paradigm challenging subjects can possibly get it all right. It may well be that some of Fell’s work is erroneous or partly so. But this does not invalidate his thesis as a whole. After all, it would only take one correct decipherment, dated and provenienced correctly, to prove Fell right. There is much more than that. Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Donal B. Buchanan, Secy/Treasurer of The Epigraphic Society, and Editor, ESOP, for reading, commenting on, and suggesting corrections for this article. An excerpt from his comments follows: Nice treatment of Fell, if somewhat rosy. Fell COULD and DID make errors (and would admit them eventually; he always fought mightily in defense of his decipherments). I know, for instance, that in one case he read an Iberic inscription backwards and across the puncts (dividing marks used in some ancient scripts --rather like reading a word across a period or semicolon). This does not really matter. What matters is that I would not have had the knowledge to spot that if I hadn't studied Iberic --and I studied Iberic because I was inspired by Fell. And because of all the times he was RIGHT. References: Fell, Barry: America B.C., Pocket Books, NY, 1989; (2006 reprint by Artesian Publishers) —— Bronze Age America, Little Brown & Co; Boston, 1982 Websites with information relating to the work of Barry Fell: The Epigraphic Society website: http://www.epigraphy.org/index.php The Equinox Project is an organization that currently supports the work of Barry Fell: http://www.equinox-project.com/drfell.htm Lesser, W. Hunter: “How Science Works - And How It Doesn't,” The West Virginia Archeologist Volume 41, Number 1, Spring 1989: http://cwva.org/ogam_rebutal/lesser_how_sci_works.html 12 Straight Talk about God website: http://asis.com/~stag/americab.html History Channel website: http://boards.historychannel.com/thread.jspa?threadID=935&start=0 ESOP Vol. 13; contains Fell’s work on the Las Lunas Decalogue: http://216.239.51.104/search?q=cache:KogInY6xdfwJ:www.epigraphy.org/volume_13.ht m+The+las+Lunas+Decalogue+%22Barry+Fell%22&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=2&gl=us Fell, Barry: “Christian Messages in Old Irish Script Deciphered From Rock Carvings in W. VA” Wonderful West Virginia, 47(1): 12-19: http://cwva.org/wwvrunes/wwvrunes_3.html Irish in America Before Columbus: http://www.aislingmagazine.com/aislingmagazine/articles/TAM17/Columbus.html Trans-oceanic Connections of the Ancient Americans: http://www.trends.net/~yuku/tran/tran.htm Some megaliths, stone structures, and dolmans can be viewed at: http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=10510 http://www.stormfront.org/whitehistory/hwr6c.htm http://unmuseum.mus.pa.us/mysthill.htm The Djed Festival of Osiris: http://www.egyptianmyths.net/djed.htm