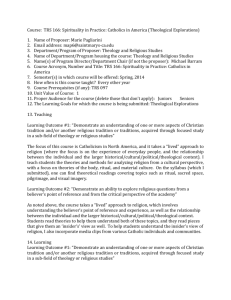

STAUROLATRY (Stau[v]vroproskynesis) AND THEOSIS:

advertisement

![STAUROLATRY (Stau[v]vroproskynesis) AND THEOSIS:](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007575791_2-95a9ad73da0f404212c867cb11476900-768x994.png)

STAUROLATRY (Stau[v]roproskynesis) AND THEOSIS: THE IMPLICATIONS OF THE INTERSECTION OF HORIZONTALITY AND PERPENDICULARITY FOR ORTHODOX HESYCHASTIC THOUGHT Archbishop CHRYSOSTOMOS In the Eastern Christian tradition, theology can be described as a kind of conceptual palimpsest, arranged in layers of understanding that pass from the literal to the metaphorical to the noetic. This is not untrue of some Western Christian theological traditions, and especially those which build on the non-Scholastic medieval mystics. However, in the West, where systematic theology and rationalism have played such an important role in religious thought, such traditions are more adventitious or eccentric than deliberate, as they are in the East. In this image of a palimpsest that I have attributed to Eastern Orthodox theology, the conceptual layers through which one moves in grasping the core of truth are not unrelated accretions of thoughts and ideas on separate planes; they do not divide the literal from the metaphorical from the theological and noetic. Rather, they integrate these three dimensions, deliberately moving thought through different layers of understanding and thus capturing the whole as a composite that no single layer is adequate to grasp, but which also loses its integrity and internal unity, except in the case of direct spiritual epiphanies, if it is not formed in an ascendancy from spiritual empiricism to spiritual theory (pneumatike theoria). It is within this theological tradition that I would like to make a few very basic but, I hope, thought-provoking comments about the four cardinal points, the theme of this fascinating conference, the Cross, and staurolatry (from the Greek “Stau[v]ros,” or “Cross,” and “latreia,” or “worship”); or, more precisely, in the Greek theological lexicon, stau[v]roproskynesis (again, from the Greek word for “Cross” and the Greek word for “veneration”: “proskynesis”), since the Cross, in the Eastern Church, is not an object of worship, as the word “staurolatry” would suggest, but an object of veneration, as clearly indicated in the decrees of the Seventh Oecumenical Synod held in Nicaea in 787. Let me begin by saying that the Cross is assuredly venerated in the Eastern Church as a physical object. Though this fact is not directly related to the observations which I would like to make about its theological meaning and the notions of horizontality and perpendicularity, the Cross as a literal object is the first conceptual layer that we must consider in moving on to its metaphorical significance and its symbolism at a noetic level. As a physical object, a Cross is formed by the intersection of a horizontal and vertical line, corresponding roughly to the horizontal and perpendicular axes of the Cartesian coordinates. If inscribed in a square, the end-points of its arms form the four cardinal points, while the quadrants formed within the square define, among other things, the positive and negative values of the trigonometric functions. If two Crosses are made to intersect, their three-dimensional presentation entails all of the geographic cardinal points: North, South, East, West, Nadir, and Zenith. To understand the universality of the Cross in its metaphorical and noetic sense, we must first acknowledge that the Cross unites, for the Eastern Christian believer, all of these elements of empirical universality, reinforcing the notion that the physical Cross is more than an external symbol—more 1 than an inscription—and reflective of cognitive markers which, even in primeval times, were imprinted on human consciousness: location, orientation, azimuth, and our very sense of space. It is not unusual, then, that the Cross is venerated, as it is, for its power and force as a literal physical object in Eastern Christianity. It behooves me to remark here that this notion of the literal power of the Cross, drawn, as I have said, from the cosmic significance of its very form, has played an important role in Christianity, beginning with the discovery of the True Cross by St. Helen, mother of St. Constantine the Emperor, in the early fourth century. In our contemporary sophistication, we scoff at the idea of a primal image, such as that of the True Cross, and dismiss it as the stuff of medieval ignorance. Indeed, skeptics have made universal the idea that, were all of the pieces of this putative True Cross to be collected together, they would form a Cross the height of a skyscraper. It has always been my observation that such professional skeptics come from among those too intelligent to be duped by intellectual legerdemain but not intelligent or perspicacious enough to understand that things are not “merely as they seem,” that empiricism has been abandoned by better science (one need only reflect on the ruminations of theoretical Physics, today, to aver this point), and that authenticity lies beyond the immediate and touches on what history, scientific intuition, spiritual revelation, and, in nuce, theory bring together (albeit sometimes tenuously and only in the form of compelling but ephemeral glances). As Einstein once commented to Heisenberg, in this vein, “It is the theory which determines what we observe.” Authenticity also lies beyond clichés of the kind that posit a great storehouse of relics of the Cross that have, in fact, never been measured and have never been examined, but belong to the hyperbole of banal legends perpetuated by those who, unable to fathom the unfathomable, retreat into a literalism which is unreal, an historicism which is naive, and a simplistic empiricism that began to unravel in scientific thinking as early as the middle of the last century. Let us not, then, too hastily set aside the deep convictions of early Christians and contemporary Orthodox, imagining that their insight into, and convictions about, the power of the image of the Cross and the uniqueness of the True Cross are simply matters of superstition, ignorance, and fundamentalistic rhetoric. If we fall to such facile thinking, we fiercely distort one of the layers in the cognitive palimpsest which I am trying to describe. A Greek synecdoche for the Cross is “wood”: “to timion Xylon,” or literally, the “precious Wood” or “precious Tree.” Greek Patristic literature is replete with references to the “wood” or “tree” of the Cross, as are liturgical texts and Orthodox hymnography, all of this imagery deepening and unfolding the many ideational aspects of the veneration of the Cross as a theological metaphor. There are likewise innumerable similes found throughout Greek Patristic, liturgical, and hymnographic texts that focus on the symbolism of the Cross: it is likened to the human body, which, when the arms are held out, form a Cross; to a staff; to a light in the darkness; to a weapon; to a fountain; and so on. The metaphorical dimensions of this imagery are brought together in the Tree: “to xylon tes gnoseos,” or the Tree of knowledge, the Tree of Salvation, the Tree of Life, etc. Applying the tropes and similes used by the Greek Fathers in describing the role of wood or the tree in capturing the primary cosmological events in human history, we can observe that Adam and Eve ate from the forbidden fruit of a fig tree in Paradise and lost the image of Divinity in which they were created. (Let me note just incidentally, here, that the consensus of the Greek Patristic tradition is that the tree from which Adam and 2 Eve ate was not an apple tree, but a fig tree, as evidenced by the fact that they fashioned clothing from its leaves to cover their nakedness.) By the same token, by the Tree of the Cross humans were restored to their former perfection in the sacrifice of Christ. In the Canon of the Orthodox Matins Service for the third Sunday of Great Lent, which is dedicated to the veneration of the Cross, we read several verses that illustrate this closing of the circle from the Lapsus to human restoration in the Wood or Tree of the Cross: first, the Cross is called, in one verse, “Divine Wood, ...shining on the four corners of the earth” (a rather striking reference to the cardinal points that are the focus of this conference); and then we read the affirmation that, “I died through a tree, but I have found in thee [the Cross] a Tree of Life.” Moving beyond metaphorical imagery to the metaphors of theology, we see in the very structure of the Cross a theological model of the intersection of the Divine and the human that is at the core of the Christian notion of the reconciliation of fallen man and God, of sin and perfection, of the earthly and the Heavenly. In the horizontality of one bar of the Cross, representing the human and the mundane, we capture the story of history—indeed of salvation history, or the finite linear history of events and epochs caught in time and bound by the antipodes of creation and the Parousia or of birth and dissolution. In the perpendicularity of the intersecting bar of the Cross, we see captured the Divine, the ethereal, the infinite, and that which extends beyond the antipodes of creation and dissolution to the timeless and immutable. And in the intersection of one axis with the other, we see an interaction between the Divine and the human, between the horizontal and the perpendicular, and between the finite and the infinite. This intersection and this integration (if I may use the latter word in a general way and without the necessary Christological and soteriological qualifications that accrue to an accurate understanding of how the Divine and the human are related) are reflected in the nature of Christ, the Theanthropos, or the God-Man, Who is both perfect God and perfect Man; in the humanity of man and the image of Divinity dwelling within him; in the meeting of Heaven and earth which constitutes the substance and language of liturgical worship; and, indeed, in the sacred space of sacred places in the profane space of mundane places. In every sense, the transcendence of dualism and the language of the reconciliation of the imperfect with perfection, the illness of sin with the salutary state of redemption, and time and space with eternity and the boundless are contained in the image of the Cross and the intersection of the horizontality of the finite with the perpendicularity of the infinite. If metaphorical theology uses simile and symbol to approach the ineffable, there is a deeper kind of theology that rises above metaphorical knowledge and touches on noetic understanding. This theology is, in many ways, encompassing and integrative, in that it brings to bear Christian theology, anthropology, soteriology, and cosmology on the very question of the structure of existence and being. In this realm, too, the symbol and metaphor of the Cross, raised to a new level of spiritual experience, serves as a didactic tool and universal cognitive key or marker. The noetic aspects of theology in the Eastern Church were fully developed in the fourteenth century by the Hesychasts, whose theological discourses—often, at least in the past, considered by polemical or biased Western theologians to be innovative or to represent an abrupt change in Orthodox theological methodology—are, in fact, a synthesis of the consensio Patrum, the phronema (or mind) of the Greek Fathers, and the ethos and consciousness of an un- 3 broken chain of spiritual development reaching back to the Early Church. These discourses are a simple recapitulation and more systematic explication of the empirical theological traditions of the Orthodox Church—of that “theology of facts,” as one early Church Father put it, that expresses the experience of the spiritual precepts that, though originally common to the Christian East and West, have been primarily and uniquely passed down unchanged in the hiera paradosis, or “sacred Tradition,” of the Eastern Church. The theological vision of the Greek Fathers and of the Early Christian Church differs substantially with regard to the precepts of original sin, redemptive sacrifice, human expiation, Purgatorial purification, and the merits of eternal salvation or eternal punishment for good or evil behaviors that—however simplistic this laconic summary— lie at the core of much Western Christian theological thought. In the anthropology and cosmology of the Greek Fathers, man, because of the Lapsus, suffers under an ancestral curse, having become spiritually and psychically ill. In the soteriology of these Fathers, the Incarnation of Christ, in which human flesh was deified by God’s assumption thereof, represents a restoration of the Divine image in man, marred and darkened by the illness of sin, and his participation once more in Divinity; in the words of the Second Epistle of St. Peter, “having escaped corruption” through Christ, human beings have become once more “partakers of the Divine nature” (1:4). As an aphorism repeated in almost identical form by a number of the earliest Church Fathers so aptly describes this soteriological process, “Christ became man that man might become Divine.” The restoration of man by Christ’s transformation of the human potential, endowing mankind with the possibility of Divinity, recasts the Western notion of salvific expiation in new (albeit more ancient) terms, equating salvation with photismos, or enlightenment, the cure of an ancestral psychic curse or illness, and theosis or divinization. Indeed, this process of restoring the body, the senses, the mind, the soul, and the whole of the human being, not just to their pre-Lapsarian status in Paradise, but even to a greater glory, is, in the words of the great Greek theologian, St. Maximos the Confessor, who flourished in the seventh century, a restructuring of the human being in essential unity with the universe. It is the very reconciliation of all that man and nature are (their logoi, as the Saint expresses it) with the Logos of God, Christ. Finite man, participating in the Divinity afforded by the Incarnation of Christ, becomes a partaker in the Infinite, this very goal being the purpose and meaning of all ecclesiastical, mysteriological, and confessional elements in the Christian Church. As we said above, the symbol of the Cross and the integration, intersection, and the encounter of humanity and Divinity that its horizontal and vertical components represent give us a perfect vision of the God-Man Christ and, we might add, a physical image of the intervention of the infinite into the finite at the point where horizontality and perpendicularity meet, which point contains within itself the properties and qualities of both lines: a perfect intersection between the finite and infinite, the Divine and human, and thus, not only a Type of the Person of Christ, but of the substance of salvation as we described it above in the anthropological, soteriological, and cosmological context of the Eastern tradition. Moreover, the symbol of the Cross also helps us to understand a basic element of Hesychastic teaching; that is, that in assuming Divinity, human beings do not abrogate the transcendence of God and make mere man God Himself, but, rather, participate in the Energies of God without assuming His Essence. This may at first, at least to those whose philosophies are deliberately anthropocentric, seem to be a meaningless issue. It is not, since God, as Being, is all that is and, as all that lies beyond 4 what is, is also Non-Being. (Parenthetically, as I often point out to my students, the affirmation of the non-existence of God by doctrinaire atheists is, ironically enough, in proper Orthodox theology an affirmation of God in His non-being.) In His Essence, then, God is beyond existence, beyond created beings, and beyond that which created, existent beings become when they participate in His Divinity. The very Identity of God rests in our inability to circumscribe that Identity, thus making it necessary to stipulate that God, as we grasp Him in the infinite verticality of one component of the Cross, does not, when He enters into finite human existence, which we in turn represent along the horizontal component of the Cross, relinquish His Essence in extending, by His energies, the antipodes of existence (life and death) into eternity. The integrity of horizontality and perpendicularity remain fully intact in this symbol, just as their perfect point of intersection brings together the quality of both without violating the peculiarity of either or the transcendence of verticality. Though in strict theology, the axes of the Cross do not represent equal and conceptually isomorphic elements, but are separated, among many other things, by the Essence-Energy distinction which I have only briefly and inadequately described, here, they are a perfect didactic model by which to grasp a basic understanding of the notion of theosis, or human deification, Incarnational theology, the subtle relationship between the finite and the infinite, the dimensions of humanity and Divinity, and the transformation of the horizontality of human life by its intersection with the perpendicularity of the Divine. Hence, the universalism of the Cross, its veneration in the Eastern Church, and its elevation and exaltation, not only in simile and metaphor, but as a noetic expression of human existence and the Divine Economy. The Most Rev. Dr. Chrysostomos is former Executive Director of the U.S. Fulbright Commission in Romania. He received his graduate education in Byzantine history at the University of California, his Licentiate in Theology at the Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, and his graduate schooling in psychology at Princeton University. He taught, as a Preceptor, at Princeton University, where he received his doctorate, and has held professorial appointments at the University of California, Ashland University, the University of Uppsala, in Sweden, and, as a Fulbright Scholar in Romania, at the University of Bucharest, the Al. I. Cuza University, and the Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism. He has twice been a Marsden Research Fellow (at Oxford University and at the Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies) and was a Visiting Scholar at the Harvard Divinity School and a Fellow of the National Endowment for the Humanities. He is at present the David B. Larson Fellow in Health and Spirituality at the John W. Kluge Center of the U.S. Library of Congress. 5