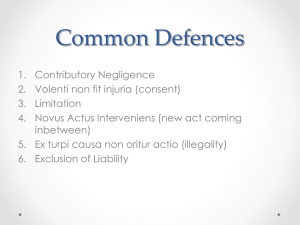

THE LAW OF TORT

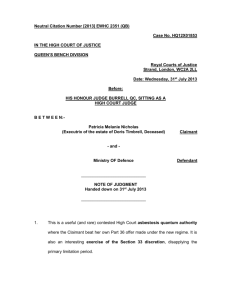

advertisement