1.3 What is not croup? - Calderdale & Huddersfield NHS Foundation

advertisement

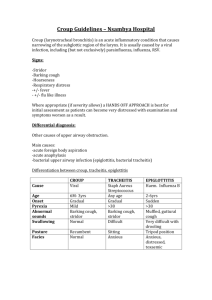

Management of Croup in children aged over three months Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Trust Guidelines for the management of croup in children aged over three months Purpose of guideline These guidelines were developed in order to reduce variance and promote best practice for the management of croup in the emergency departments of the Trust. Scope and Locations where this guideline applies The guidelines apply to all nursing and medical staff involved in the care of children aged over three months who present with croup at the emergency departments of the Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Trust. It reflects what is currently regarded as safe practice, but does not replace the need for the application of clinical judgement to each individual presentation. Contents Background ............................................................................................................ 2 Local Issues ............................................................................................................ 2 Guideline at a Glance 3 Flow Chart 5 Detail of recommendations and supporting evidence. 6 References, including national guidelines ........................................................... 14 Guideline developed by: ..................................................................................... 14 List of interested groups....................................................................................... 14 Distribution list and areas where guideline should be readily available .............. 14 Arrangements for training .................................................................................... 15 List of changes and dates of changes 16 Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 1 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months Background Croup is a common cause of upper airway obstruction in young children. It is usually mild and self-limiting, though occasionally it may cause severe respiratory obstruction [1]. Before the widespread use of corticosteroids, studies reported that as many as 31% patients with croup required hospitalisation and 1.7% required intubation [2]. Acceptance of the use of corticosteroids for the treatment of croup for the last decade has dramatically reduced the number of patients requiring admission to hospital and endotracheal intubation [3]. Croup, also known as laryngotracheobronchitis, is a clinical syndrome of a hoarse voice, barking cough and inspiratory stridor [3]. It is usually caused by a viral infection of the upper airway that results in inflammation of the larynx, trachea and bronchi, thereby compromising airflow through the proximal airway. A number of viruses may cause croup, although the most common are parainfluenza 1 and 2 and respiratory syncytial viruses [4]. It mostly affects children between 6 and 36 months, although it may occur in older children [5]. Most patients have an upper respiratory tract infection for several days before cough becomes apparent. With progressive compromise of the upper airway, a characteristic sequence of symptoms and signs occurs. At first there is a mild brassy cough with intermittent inspiratory stridor. As obstruction increases, stridor becomes biphasic and is associated with worsening cough, nasal flaring, and suprasternal, infrasternal and intercostal retractions. As inflammation extends to the bronchi and bronchioles, respiratory difficulty increases. The child’s temperature may only be slightly elevated; it rarely reaches 39-40oC. Symptoms are characteristically worse at night and often occur with decreasing intensity for several days [6]. Local Issues Traditionally, the emergency departments at Huddersfield Royal Infirmary and Calderdale Royal hospital have differed in their approaches to management of croup. Therefore, the purpose of this guideline is to provide a systematic and standardised approach to care. Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 2 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months Management of Croup in children aged over three months Guideline at a Glance 1. Diagnostic criteria should include: further points page 6 An appropriate history Croup symptoms Clinical examination Exclusion of other causes of upper airway obstruction: Table (1) p.7 2. Assessment of severity: further points page 7 Utilize the Westley Croup Scale (WCS): p.8. C Complete assessment of respiratory function including, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and heart rate should supplement the WCS. D Assessment of airway obstruction: p. 9 3. Treatment: further points page 10 All parents should receive appropriate verbal advice and be given a copy of the information leaflet on croup. 3.1 Mild No specific treatment Mild croup does not need pharmacological treatment. There is evidence to suggest the use of mist therapy is ineffective. Parental advice Discharge home- see key factors for admission. p.11 3.2 Moderate Children with moderate croup who demonstrate stridor and chest wall retractions should receive : Corticosteroids- Oral dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg if not tolerated nebulised budesonide 2mg should be considered. A Whilst oral, intravenous, intramuscular and nebulised corticosteroids are all efficacious, the use of oral corticosteroid is kindest to the patient, easy to administer and inexpensive. Discuss with on-call paediatrician and arrange for transfer to paediatric assessment unit Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 3 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months 3.2 Severe croup Children with severe croup should receive systemic corticosteroids and nebulised adrenaline, unless contraindicated, and be assessed by a senior paediatrician in the emergency department. The child must be stable before transfer to the paediatric ward. Rarely children with severe airway obstruction will need transfer to the PICU in Leeds. Oxygen – Immediate treatment for severe viral coup with significant oxygen desaturation. D Corticosteroids- Oral dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg if not tolerated nebulised budesonide 2mg should be considered. A Adrenaline -nebulised adrenaline 0.4mg/kg (maximum 5mg). A Remember these are only guidelines, individual presentations or circumstances may require alternative treatments and management. Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 4 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months Management Flowchart CROUP Exclude other causes of upper airway obstruction Life Threatening Airway Obstruction? (Cyanosis or Decreased Consciousness?) No Yes Do not disturb the child unnecessarily Administer high flow oxygen Call Senior A&E, Paediatrics and Anaesthetist Assess Severity Mild Croup? Moderate Croup? Severe Croup? Barking Cough. Stridor at rest Nil or intermittent stridor. Tracheal tug and chest retractions Biphasic stridor at rest Apathetic or restless Marked tracheal tug. WCS 2-7 WCS 8 or more Dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg oral Call Senior Paediatrician and senior A&E Dr. WCS </= 1 No Specific treatment. Parental explanation and advice sheet. Or if oral not tolerated Competent parents, transport available. 2mg Nebulised Budesonide No extenuating circumstances Discuss with on-call paediatrician and arrange for transfer to paediatric assessment unit for observation Disturb as little as possible. Oxygen Discharge Home Nebulised Adrenaline 5mls 1: 1000 Dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg Or Budesonide 2mg nebulised if oral steroids not tolerated. Consider need for intubation and PICU Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 5 of 16 Do not move from Emergency Department until child has been assessed by senior Dr. and is stable. Management of Croup in children aged over three months Detail of recommendations and supporting evidence. 1. Diagnosis 1.1 Distinguishing viral from spasmodic croup Typically viral croup develops over days with a concurrent typical coryzal illness and the symptoms of airway obstruction disappear over 3-5 days [3]. Conversely, spasmodic croup is said to be more common in atopic older children and comes on rapidly overnight in children who were perfectly well when they went to sleep [7]. Spasmodic croup often runs a shorter clinical course [8]. However, the history and assessment of airway obstruction will determine treatment rather than the sometimes erroneous subclassification of its aetiology [9]. 1.2 Diagnostic criteria should include: 1.2.1. An appropriate history (Child typically aged 6-36 months. Usually 2-3 days coryzal symptoms, often low grade fever, usually happy to eat and drink, often presents at night) 1.2.2. Croup symptoms (Hoarse voice, barking cough, inspiratory stridor) 1.2.3. Clinical examination (Non-toxic child, well-perfused, possible tracheal and intercostal recessions) 1.2.4. Exclusion of other causes of upper airway obstruction (Table 1, page 6). Only when all 4 criteria are satisfied should the clinical condition of croup be diagnosed [6]. D 1.3 What is not croup? There are a number of structural and infective conditions that cause upper airway obstruction. These may be thought of anatomically [Table (1) p.7]. In addition there are three factors to consider when deciding whether the presence of stridor and use of accessory muscles of respiration relate to croup or an alternative diagnosis [10]. 1.3.1. Age of the child. A child less than 3 months of age is more likely to have a structural airway problem (e.g. laryngomalacia) with or without a concurrent viral infection. Similarly, tracheomalacia may present with a brassy cough and variable stridor. A child between 1 and 3 years with the acute onset of respiratory difficulty without fever may have inhaled a foreign body. Bronchial foreign bodies will usually have an associated localised expiratory wheeze (rather than inspiratory stridor) and may have evidence of air trapping on an expiratory chest x-ray below the level of the obstruction (ball-valve effect). Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 6 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months 1.3.2. Character of the stridor. The combination of inspiratory and expiratory stridor increases the likelihood of an underlying fixed tracheal obstruction (e.g. retropharyngeal abscess). These children need urgent assessment. 1.3.3. Toxicity of the child. Children with croup do not appear toxic (pale, very febrile and poorly perfused). This is more commonly seen in bacterial tracheitis or epiglottitis. Table (1.) Causes of upper airway obstruction Supraglottic Acute tonsillar enlargement Epiglottitis Retropharygeal Abscess Foreign Body Acute Angioedema Laryngeal/ subglottic Viral croup Spasmodic croup Laryngomalacia Bacterial Tracheitis Foreign Body Diptheria Thermal/Chemical Injury Intubation Trauma Laryngospasm Tracheal Trauma (haematoma) Foreign Body Bacterial tracheitis Congenital Abnormality Tumour The differential diagnosis of upper airway obstruction should always be considered before presuming that the child has croup. There is no diagnostic or management aid from radiological investigations in children with uncomplicated croup. 2. Assessment of Severity Although infrequent, severe airway obstruction is the major clinical concern in croup. Determining the degree of airway obstruction is therefore the most important aspect of assessment. It relies almost always on clinical signs. There are validated tools to aid the assessment of the severity of croup [11,12,13]. 2.1 Westley Croup Score (WCS) The use of the Westley Croup Score Scale (Table 2) for objectively classifying the severity of croup, into mild, moderate or severe is recommended for use in the emergency departments [11]. C The evaluation and documentation of a complete assessment of respiratory function including respiration rate, oxygen saturations and heart rate should supplement the use of the WCS in assessing the severity of croup. D Airway obstruction in croup can worsen rapidly; therefore repeated careful clinical assessment is essential. Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 7 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months Table (2.) Westley Croup Score Scale [11] Score Symptom Severity Stridor Retractions Air Entry Cyanosis in Room Air Level of Consciousness None When agitated At Rest None Mild Moderate Severe None Decreased Markedly Decreased None When agitated At rest Normal Disorientated Total 0 1 2 0 1 2 3 0 1 2 0 4 5 0 5 Total Score Croup Score 0-1 Mild Croup Croup Score 2-7 Moderate Croup Croup Score >/=8 Severe Croup 2.2 Oximetry Oximetry is a useful routine tool in the emergency department. However, it can never substitute good clinical assessment. It has been demonstrated that oxygen saturation may be near normal in severe croup and yet significantly lowered in some children with mild to moderate croup. This is presumed to relate to lower airway disease causing ventilation/perfusion mismatching. 2.3 Important points to consider when assessing severity: 2.3.1. General appearance. A child who is agitated, appears to be tiring from the effort of breathing or has a decreasing level of consciousness has severe croup and needs to be closely monitored. 2.3.2. Degree of respiratory distress. The presence of stridor at rest, tracheal tug, and chest wall retractions, changing respiratory rate and pulse rate or palpable pulsus paradoxus indicate treatment is necessary. Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 8 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months 2.3.3. Cyanosis or extreme pallor The presence of cyanosis or extreme pallor indicates the need for immediate treatment. 2.3.4. Oxygen desaturation Oxygen desaturation as indicated by pulse oximetry is a LATE sign and an unreliable measure of croup severity. 2.4 Assessment of airway obstruction 2.4.1. Mild Airway Obstruction (WCS 0-1) This child will usually appear happy and be prepared to drink, eat, play and take an interest in the surroundings. There may be mild chest wall retractions and mild tachycardia, but stridor at rest should not be present. No pharmacological treatment is needed. The parents should be reassured, given an explanation of what to expect over the coming days and be provided with an information sheet (Note: other factors may warrant hospital admission, see page 11). 2.4.2. Moderate Airway Obstruction (WCS 2-7) This is indicated by persisting stridor at rest, chest wall retractions, use of accessory muscles of respiration and increasing heart rate. The child can be placated and is interactive with people and surroundings. The child will need systemic corticosteroids and be admitted for observation for a minimum of four hours. If the child continues to have stridor at rest, then further treatment will be considered with prolonged observation. 2.4.3. Progression from Moderate to Severe Obstruction The child may begin to appear worried, preoccupied or tired. The child may sleep for short periods. This child will require close, continuing observation, treatment with systemic corticosteroids and nebulised adrenaline with regular (minimum 30-6- minutes) clinical review. Progression of signs will indicate the need for medical assessment and consideration of further treatment with systemic corticosteroids and adrenaline. 2.4.4. Severe Airway Obstruction (WCS >/=8) As airway obstruction increases, the appearance will be that of increasing tiredness and exhaustion. Marked tachycardia is usually present. Restlessness, agitation, irrational behaviour, decreased consciousness, hypotonia, cyanosis and marked pallor are late signs indicating that dangerous airway obstruction is now present. The child should not be unnecessarily disturbed other than the immediate application of mask oxygen with nebulised adrenaline as preparations are made to intubate the child by someone skilled in paediatric intubation (ideally with an inhaled induction). Systemic steroids, if not previously given, will be administered once the airway is secured. Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 9 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months 3. Treatment The most important change in the management of croup has been the earlier and liberal use of corticosteroids the emergency department [5]. In writing the guidelines other common therapies for croup have been considered. 3.1. Mist Therapy The use of steam inhalation for treating croup has been advocated since the 19th century [7]. More recently a randomised controlled trial (RCT) examined the effect of mist in the treatment of mild to moderate croup [14]. B They concluded there were no benefits of mist therapy in terms of reduction in croup score, or the duration of symptoms. However, they reported no adverse effects, and parents who report relief from nursing their children in steamy bathrooms should not be actively persuaded to avoid this practice. B 3.2. Oxygen Oxygen is the immediate treatment of choice for children with severe viral croup who have significant oxygen desaturation. D 3.3. Corticosteroids The Cochrane Library has recently published the results of a systematic review of RCTs concerning the effectiveness of glucocorticoids for croup [15]. The conclusion of this review was that dexamethasone and budesonide are equally effective in relieving the symptoms of moderate and severe croup as early as six hours after treatment. A Dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg has been shown to be as effective as 0.3mg/kg and 0.6mg/kg via the oral route [16, 12]. A Oral dexamethasone has been shown to be as effective intramuscular dexamethasone [17,18]. A In application of the evidence with consideration to patient preference and cost, it is recommended that oral administration of dexamethasone 0.15mg/kg should be given to children with moderate and severe croup. If oral medication is not tolerated nebulised budesonide 2mg should be considered. A 3.4. Adrenaline Racemic adrenaline has been demonstrated to give short term relief of symptoms (2-3hours) of moderate and severe croup [19]. A L-adrenaline (more readily available) has been demonstrated to be equally effective as racemic adrenaline (Not usually available outside the USA) in the treatment of croup [20]. A Thus it is recommended that nebulised adrenaline 0.4mg/kg (maximun 5mg) be administered to children with severe croup. A Note it is contraindicated in children with ventricular outflow obstruction (e.g. tetralogy of fallot). Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 10 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months Close monitoring and observation should be made to identify any side effects of this treatment (e.g. cardiac arrhythmias). 3.5 Other factors for hospital admission In particular, the following factors are more likely to increase the need for admission to hospital despite having clinically mild croup: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Age less than 6 months Known structural airway anomaly (e.g. subglottic stenosis) Inadequate fluid intake Parental anxiety Proximity of home to hospital/transport issues Representation to the emergency department within 24hours Uncertain diagnosis If in doubt always seek senior A&E or Paediatric opinion. Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 11 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months Strength of recommendations (Based upon SIGN the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network classification) A Based on meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials and directly applicable to the population. B Based on high quality case controlled or cohort studies or systematic reviews and directly applicable to the population or evidence extrapolated from meta-analysis or randomised control trials. C Based on lower quality case controlled or cohort studies directly applicable to the population or evidence extrapolated from high quality case controlled or cohort studies. D Based on non-analytical evidence such as case reports or expert opinion or evidence extrapolated from lower quality case-controlled or cohort studies. Recommended best practice based on the clinical experience of the guideline development group Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 12 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months References [1] Fitzgerald DA, Kilham HA. Croup: assessment and evidence-based management. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2003; 179: (7), 372-377 [2] Marx A, Torok TJ, Holman RC, Clarke MJ. Pediatric hospitalisations for croup (laryngotracheitis): biennial increases associated with human parainfluenza virus 1 epidemics. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1997; 176: 1423-1427. [3] Klassen TP. Croup. A current perspective, Pediatric Clinics of North America. 46. 1999; 1167-1178. [4] Hendrickson KJ, Khun SM, Savatski LL. Epidemiology and cost of infection with human parainfluenza virus types 1 and 2 in young children, Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1994; 18: 770-779. [5] Knutson D, Aring A. Viral Croup. American Family Physician. 2004; 69: (3), 535542. [6] Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 16th Edition. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2000. [7] Skolnik N.S. Treatment of croup: a critical review, American Journal of Diseases in Children. 1989; 143: 1045-1049. [8] Fitzgerald DA, Mellis CM. Management of acute upper airways obstruction in children. Modern Medicine in Australia. 1995; 38: 80-88. [9] Ausejo M, Saenz A, Pham B, Kellner JD. Johnson DW, Moher D, Klassen TP. The effectiveness of glucocorticoids in treating croup: meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 1999; 319: 595-600. [10] New South Wales Department of Health. Acute Management of Infants and Children with Croup, Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2003. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au [11] Westley CR, Cotton EK, Brooks JG. Nebulized racemic epinephrine by IPPB for the treatment of croup. American Journal of Disease in Children. 1978;132: 484-487. [12] Geelhoed GC, Macdonald WB. Oral and inhaled steroids in croup: randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1995; 20: 355-361. a [13] Bjornson C, Klassen TP, Williamson J, Brant R, Plint A, Bulloch B. The use of dexamethasone in mild croup: A multi-centre randomised controlled trial. Pediatric Academic Societies. 2003 May: 3-6. [14] Neto, Kentab, Klassen et at 2002- no reference [15] Russell & Wiebe, Saenz, 2004 – no reference Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 13 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months [16] Geelhoed GC, Turner J, Macdonald WB. Efficacy of a small single dose of oral dexamethasone for outpatient croup: a double blind placebo controlled clinical trial, British Medical Journal, 1996; 313: 140-142. [17] Donaldson D, Poleski D, Knipple E, Filips K, Reetz L, Pasual RG, Jackson RE. Intramuscular versus Oral Dexamethasone for the Treatment of Moderate-to-severe Croup: A Randomized, Double-blind Trial. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2003, 10: (1), 16-21. [18] Rittichier KK, Ledwith CA. Outpatient treatment of moderate croup with dexamethasone: intramuscular versus oral dosing. Pediatrics, 2000; 106: 1344-1348. [19] Kristjansson S, Berg-Kelly K, Winso E. Inhalation of racemic adrenaline in the treatment of mild and moderately severe croup. Clinical symptom score and oxygen saturation measurement for evaluation of treatment effects. Acta Paediatrica. 1994; 83: 1156-1160. [20] Waisman Y, Klein BL, Boenning DA, Young GM, Chamberlain JM, O’Donnel R, Ochsenschlager DW. Prospective randomised double-blind study comparing Lepinephrine and racemic epinephrine aerosols in the treatment of laryngotracheitis (croup), Pediatrics. 1992; 89: (2), 302-306. Guideline developed by: Insert authors and responsible body Authors: Janet Youd: Nurse Consultant Group name Paediatric Consultants A&E Consultants List of interested groups Information Requires only Sign-off DATS Medicines management committee Clinical Guidelines Steering Group Date signed off Distribution list and areas where guideline should be readily available Listing first the intranet or internet site then other sites. Intranet A&E Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 14 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months Arrangements for training Training coordinator: Janet Youd Groups requiring training: A& E Doctors and nurses Paediatric doctors and nurses Frequency of training: Initial implementation of guidelines then updates as guidelines reviewed Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 15 of 16 Management of Croup in children aged over three months List of changes and dates of changes Date change Change (with paragraph reference) implemented Draft Version 1.0 May 06 Page 16 of 16 Who is Full signresponsible for off required change (no or fully signed off)