Here

advertisement

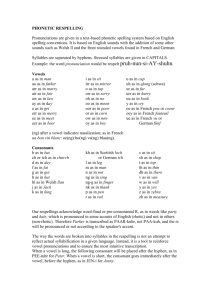

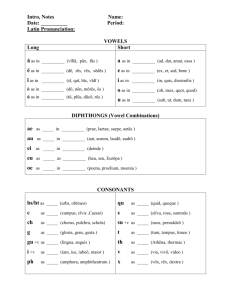

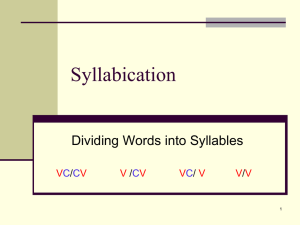

Aikido Gakko Ueshiba A Guide To Pronouncing Japanese Reference 1. A little Background Skip this section if you want to go straight on with pronunciation. For those interested... The Japanese language is constructed of very straightforward phonic elements, with only a few special rules modifying the basic structure. Looking at the language as though it were written in the Roman Alphabet, each word consists of one or more syllables and occasional double consonants. Syllables are either individual vowels, a consonant followed by a vowel or ‘n’. Each syllable is spoken with the same metre length, or a vowel sound (alone or after a consonant) may have its length doubled. So the Japanese language is a very even paced, vowel heavy language. Emphasis is given by pitch rather than stress and this can give it a very “singsong” quality, especially when spoken by women. Japanese has two written forms that are used together; the ancient symbols adopted from the Chinese and a native Japanese syllabary (also in two forms). It is usually considered that a basically educated Japanese should know at least two thousand of the Chinese symbols and the roughly one hundred or so Japanese syllabic characters. So, in the English speaking world it is more normal to represent Japanese writing using our own Roman alphabet. As you will see this can present a few problems. A Japanese symbol usually has at least two different pronunciations, one based on the Chinese language and the other on its Japanese equivalent, but these sounds once learned are fixed and known. The Japanese syllabary is used more like our alphabet; each character represents a component of the Japanese language sounds. Our own alphabet splits this down to the level of parts of a syllable, but the Japanese syllabary operates on whole syllables with consistent vocalisation. This actually makes the Japanese easier to learn and pronounce correctly, for example... English: “cu” in “cut” and “cu” in “cute” Japanese: “ku” is used where we would use “cu” always pronounced like the English “cu” in “cut”, “ku” in “kuru” but softened very slightly. and “ku” in “kutsu” } The Japanese syllabary can be used to write the whole language, replacing the Chinese symbols, because it represents all of the languages sounds. Note: just to confuse matters further, the roughly 100 characters of the syllabary are actually in two halves. Each half has the same set of sounds, but the characters used are slightly different. The first half (the Hiragana) uses rounded characters and is used for native Japanese words. The second half’s characters (Katakana) are more angular and are used when writing words imported from other languages or technical/scientific terms. In “Romanising” the Japanese sounds using our own alphabet, two main methods have been developed the commonest of which is the “Modified Hepburn System”, based around original attempts by Hepburn. This is the method described in this text. When Japanese is written in Romanised form the Japanese call it “Romaji” script. A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.1 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 TEMPLEGATE DOJOA Guide To Pronouncing Japanese Reference Reference 2. Pronunciation Guide What follows is a staged guide to pronouncing Japanese and writing it using the Roman alphabet (“Romaji”). The sections are:A description of how the Japanese sounds are represented using the Romaji alphabet. Rules for the overall pronunciation of Japanese. Descriptions of the small number of rules governing changes in pronunciation with certain syllable combinations. Tables of the Japanese syllabary, represented using Romaji alphabet using the modified Hepburn system. These define all the sounds of the Japanese language with pronunciation examples (where possible). A selection of examples. Some pitfalls and things beyond the scope of this text. The simplest approach is just to use the syllabary tables and just go with the flow. Don’t worry too much. 2.1. Romanising The Syllabary i. The modified Hepburn system is used below. It represents the Japanese syllabary using the Roman alphabet. In this system each vowel is represented as we represent our own vowels “a”, “e”, “i”, “o” and “u”. The syllables are then represented by prefixing the vowels with an appropriate consonant (see the example above for “ku”). The only single consonant syllable in Japanese is “n”. ii. Double length syllables are always caused by lengthening a vowel and this is shown by placing a diacritic dash mark over the vowel (“ku” - single length syllable, “k_” - double the syllable length). iii. Double consonants are possible, but these are always pronounced distinctly. They are represented by a doubling of the consonant in spelling (“kekkon” - marriage). iv. The “s” consonant also has an “sh” form in combination with vowels and this is written as “sh” when it occurs. v. The “t” consonant is never used in direct combination with “i”. It is always sounded as the “chi” in “chip” (see 2.3.5. below). It is represented as “chi”. vi. The “t” consonant is never used in direct combination with “u”. It is always modified to a slight “t” sound preceding “su” (see 2.3.6. below). It is represented as “tsu”. vii. The “h” consonant is never used in direct combination with “u”. It is always sounded like a breathy “f” started with a microscopic “h” sound (see 2.3.7. below). It is represented as “fu” viii. Japanese also allows for modified vowel sounds in the consonant/vowel syllables. The modification is always to merge a “y” sound into the front of the vowel. This is shown by:Adding a “y” between most consonants and the vowel in spelling (for example, “kyu”). Adding an “h” between “s” and the vowel in spelling (for example “sha”). Replacing “t” with “ch” before the vowel in spelling (for example “cho”). Replacing “z” with “j” before the vowel in spelling (for example “ju”). A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.1 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 Aikido Gakko Ueshiba A Guide To Pronouncing Japanese Reference ix. Although the Japanese have two versions of the written syllabary, Hiragana and Katakana (see 1. above), each version is phonically the same. The modified Hepburn Romanisation does not distinguish between these two forms. 2.2. General Pronunciation Rules i. Japanese is an evenly metred language, where each syllable of a word is given the same length. ii. Syllables consist of either a vowel alone or a consonant followed by a vowel or a vowel compounded with “y”. For example:“ku” and the compound “kyu”; “ru” and the compound “ryu”. The “y” is rolled into the “u” to form a single sound. Also there is no separation between the consonant and the “y” sound. This does not alter the hardness of the vowel (see below). For example:The “ya” in “kya” is pronounce as in “yap” not as in “yale”. Note: that “s” is replaced with the “sh” of “shire” and “t” is replaced with the “ch” sound of “church” before a “y” compounded vowel. “Z” forms “y” compound syllables as well, but these are pronounced as though “j” is coupled with the vowel alone (e.g. “jo”, not “zyo”) and this is slightly softened like “u” (see 2.3.2. below). iii. The only none vowel syllable is “n” alone. It is pronounced just like the English terminal “n” (e.g. in “gun”), but is always given a full syllable length. iv. Vowel sounds are mostly hard when pronounced correctly. For example:“koku” (traditional rice measure) is pronounced as “koku”, not “kookew”. “co” as in “cot” “co” as in “cone” or “coot” v. A double length vowel sound is still pronounced as a single length vowel; they sound is simply dragged out to twice the length of the single. vi. Double consonants may be found in the middle of words. These are always pronounced as separate items. For example:“kekkon” (marriage) is pronounced as “kek” “kon”, not “kekon”. The pause between consonants is very brief, more of a short stagger than a word break. vii. Where vowels follow immediately after another vowel the two sounds tend to roll together, but each vowel has its full length and the vowel sounds should not be over modified. A classic example is the English mispronunciation of the Koi carp’s name. It is usually pronounced like “coy”, whereas it should be “ko-i”. The o rolls into the i, but both retain their short, hard sound. 2.3. A Few Exceptions To 2.2. As with any language there are common usage corruptions to the formal pronunciations and similar small variations. A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.2 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 Reference 2.3.1.Elision Of “I” The “i” vowel is frequently almost dropped from a consonant/vowel syllable when in the middle of a word and followed by a consonant with a hard opening sound like “k”, “t” or “p”. This loss leaves only the slightest of “i” sounds behind and the syllable length also drops. For example:“yoroshiku” ( I beg you) is pronounced “yo-ro-shku” rather than “yo-ro-shi-ku”. 2.3.2. Softening Of “U” In 2.2., iv. above it indicates that most of the vowels use a short, hard sound. “U” is the exception. It is usually softened slightly to something like the “u” in “super”, but the lips do not move forwards. It is like a halfway house between the “u” in “supper” and that in “suit”. Note: “o” also undergoes a similar, slight softening when modified by “y” (see 2.2., ii. above). 2.3.3.Elision Of “U” When “u” is the last sound in a word it is sometimes reduced almost to nothing. The commonest occurrence of this is the terminal “u” of the polite, present continuous form of a verb. These verbs end in “masu”, and it is spelled like this. However, the “u” is almost totally lost. 2.3.4. “S” Consonant/Vowel Syllables “S” syllables have two flavours. One where the “s” is pronounced raw. For example, “Satsuma”, where the “sa” is pronounced like “sad”. The second where the “s” is modified to be like the “sh” in “shut”. For example, “shaku”. The “sh” pronunciation is always used in place of “si” and syllables with “y” modified vowel sounds (see 2.2., ii. above). 2.3.5. No “Ti” The sound “ti” (as in “tip”) does not occur in Japanese. The value of “t” is always pronounced like the “ch” in “chop” before “i”. For example “hachi”. 2.3.6. No “ Tu” The sound “tu” (as in “tun”) does not occur in Japanese. The value of “t” is always pronounced like the “su” in “sun” with a slight, sibilant “t” before it. For example “tsuki”. 2.3.7. Elision Of “H” Before “U” The syllabi “hu”, is not pronounced with a strong “h” as it is in English. Instead the “h” is de-voiced and tends towards a soft, breathy “f” starting with a slight “h” sound. There is no real English equivalent. 2.3.8. No “Yi” Or “Ye” “Yi” and “ye” are not used in Japanese. They are phonically so close to the vowels “i” and “e”, respectively, that these replace them. A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.2 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 Aikido Gakko Ueshiba TEMPLEGATE DOJO A Guide To Pronouncing Japanese Reference Reference DOJO 2.3.9. No “Wi” Or “Wu” or “We” A Guide To Pronouncing Japanese “Wi”, “wu” and “we” are not used in Japanese. They are phonically so close to the vowels “i”, “u” and “e”, respectively, that these replace them. 2.4. The Syllabary The syllabary tables are laid out in Romanised syllable sets commencing with the vowels, and then sets starting with the same consonant combined with each of the vowels. The vowels and consonants are presented in the common sequence used in Japan; for the vowels that is, “a, i, u, e, o” rather than the English “a, e, i, o, u”. 2.4.1. Vowels, Simple Consonant/Vowel Syllables And “N” Syllable a Pronunciation Like the “a” in “cat”. Not like the “a” in “said” or “say”. Syllable ka Pronunciation Like the “ca” in “cat”. Not like the “ca” in “cane”. i Like the “i” in “tin”. Not like the “i” in “stile”. ki Like the “ki” in “kick”. Not like the “ki” in “kind”. u Like the “u” in “super” (see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “u” in “tune” or “sure”. ku Like the “cu” in “cut” (but see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “cu” in “cupid”. e Like the “e” in “get”. Not like the “e” in “see”. ke Like the “ke” in “ken”. Not like the “ke” in “keen”. o Like the “o” in “cot”. Not like the “o” in “cool”, “open” or “owl”. ko Like the “co” in “con”. Not like the “co” in “cool”, “cone” or “cow”. sa Like the “sa” in “sat”. Not like the “sa” in “said” or “say”. ta Like the “ta” in “tap”. Not like the “ta” in “tape”. shi Like the “shi” in “ship”. Not like the “shi” in “shine”. chi Like the “chi” in “chin”. Not like the “chi” in “china”. su Like the “su” in “sun” (but see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “su” in “super” or “sure”. tsu Like the “tsu” in “Satsuma”. Remember to voice the “t” slightly. se Like the “se” in “set”. Not like the “se” in “seep”. te Like the “te” in “ten”. Not like the “te” in “teal”. so Like the “so” in “sop”. Not like the “so” in “soon”, “soap” or “sow”. to Like the “to” in “top”. Not like the “to” in “tool”, “toe” or “towel”. na Like the “na” in “nag”. Not like the “na” in “nay”. ha Like the “ha” in “hat”. Not like the “ha” in “tape”. ni Like the “ni” in “nip”. Not like the “ni” in “line”. hi Like the “hi” in “hip”. Not like the “hi” in “hind”. nu Like the “nu” in “nut” (but see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “nu” in “nude”. fu See 2.3.2. and 2.3.6. above). ne Like the “ne” in “net”. Not like the “ne” in “seep”. he Like the “he” in “hen”. Not like the “he” in “heat”. no Like the “no” in “not”. Not like the “no” in “noon”, “note” or “now”. ho Like the “ho” in “hot”. Not like the “ho” in “hoop”, “hone” or “how”. ma Like the “ma” in “man”. Not like the “ma” in “may”. ya Like the “ya” in “yam”. Not like the “ya” in “yay”. A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.3 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 TEMPLEGATE DOJOA Guide To Pronouncing Japanese Syllable mi Pronunciation Like the “mi” in “mill”. Not like the “mi” in “mile”. mu Like the “mu” in “mull” (but see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “mu” in “mule”. me Like the “ne” in “net”. Not like the “ne” in “neat”. mo Syllable Reference Reference Pronunciation yu Like the “yu” in “yuppie” (but see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “yu” in “yule”. Like the “no” in “mop”. Not like the “mo” in “moon”, “mote” or “mount”. yo Like the “yo” in “yon”. Not like the “yo” in “you”, “yoga” or “yowl”. ra Like the “ra” in “ran”. Not like the “ra” in “ray”. wa Like the “wa” in “wan”. Not like the “wa” in “way” or “wart” ri Like the “ri” in “rid”. Not like the “ri” in “ride”. ru Like the “ru” in “rut” (but see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “ru” in “rule”. re Like the “re” in “reckon”. Not like the “re” in “reel”. ro Like the “ro” in “rot”. Not like the “ro” in “root” or “round”. wo Like the “wo” in “wok”. Not like the “wo” in “wood”, “wove”, “work” or “wow”. ga Like the “ga” in “gang”. Not like the “ga” in “gay”. za Like the “za” in “zap”. Not like the “ta” in “tape”. gi Like the “gi” in “gig”. Not like the “gi” in “giant”. ji Like the “ji” in “jip”. Not like the “ji” in “jibe”. gu Like the “gu” in “gull”. Not like the “gu” in “guru”. zu Like the “zu” in “zucchini”. Not like the “zu” in “Zulu”. ge Like the “ge” in “get”. Not like the “ge” in “gear”. ze Like the “ze” in “zen”. Not like the “ze” in “zeal”. go Like the “go” in “gone”. Not like the “go” in “goon”, “goat” or “gown”. zo Like the “zo” in “zombie”. Not like the “zo” in “zoo” or “zone”. da Like the “da” in “dagger”. Not like the “da” in “day”. ba Like the “ha” in “bat”. Not like the “ba” in “bait”. di Like the “di” in “dip”. Not like the “ni” in “line”. bi Like the “hi” in “bit”. Not like the “bi” in “bind”. du Like the “du” in “dun” (but see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “du” in “duel”. bu Like the “bu” in “but” (but see 2.3.2. above). Not like the “bu” in “bugle”. de Like the “de” in “den”. Not like the “ne” in “seep”. be Like the “be” in “bend”. Not like the “be” in “beat”. do Like the “do” in “dot”. Not like the “do” in “doom”, “dote” or “down”. bo Like the “bo” in “bop”. Not like the “bo” in “boon”, “bone” or “bower”. pa Like the “pa” in “pan”. Not like the “ga” in “gay”. pi Like the “pi” in “pig”. Not like the “pi” in “pint”. pu Like the “pu” in “pun”. Not like the “pu” in “pure”. A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.1 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 A Guide To Pronouncing Japanese Reference Syllable pe Pronunciation Like the “pe” in “pet”. Not like the “pe” in “peer”. Syllable Pronunciation po Like the “po” in “pond”. Not like the “po” in “pool”, “pole” or “power”. n This is the only word terminal consonant in Japanese, always following a vowel. Its sound varies with the vowel it follows much as the English usage of terminal vowel/n combinations. 2.4.2. Vowels Modified With “Y” Syllable Pronunciation Syllable kya sha kyu shu kyo sho cha nya chu nyu cho nyo hya mya hyu myu hyo rya Pronunciation myo See 2.2., ii. and 2.1., ii. above. gya ryu gyu ryo gyo ja bya ju byu jo byo See 2.2., ii. and 2.1., ii. above. pya pyu pyo 2.5. Examples In the following examples the words are broken down into their syllable patterns, pronounced as indicated in the tables in 2.4. above. Individual syllables are separated by spaces. where syllables tend to blend into each other (e.g. vowel following vowel) the syllables are separated by a dash and their sounds should roll into one another more. Remember thought that these are words. The syllables tend to flow into one another; don’t pause after each one just because illustrative spaces have been used. Where a letter is lost (elision) to some degree or other it is subscripted. The degree of elision is described in other parts of this text. A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.2 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 Reference Double consonants are shown by placing an additional consonant at the start of the syllable separated form it by an apostrophe. For example, ke k’ko n”. The first “k’ ” will tend to terminate the preceding syllable in pronunciation making it rather like “kek’kon”. A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.2 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 Aikido GakkoDOJO Ueshiba TEMPLEGATE A Guide To Pronouncing Japanese Reference Reference DOJO “say_nara” “Onegaishimasu” o ne ga-i shi mas . sa yoo na ra A Guide To Pronouncing Japanese u “Please” (do this for me). Notice the dropped “u”; this is the polite form of the verb “please (do)”. Also the rollng of the “ga” into the “i”. “d_mo” doo mo “Goodbye”. The doubled “_” indicates an extra polite form. It may also be said with a short “o” as a more informal goodbye. “ryote” “Thanks”. A rather brusque thank you between close friends or your peer group. More usually used to start a polite thanks phrase with “arigat_” and “gozaimasu”. Notice the doubled “o”. “bokken” 2.6. “Both hands”. Notice the “y” modified .vowel. Remember not to lengthen the “o” in response to this, nor to overemphasise the “y” making it sound like an “i”. “ai” a-i bo k’ke n “Wooden Sword”. Notice the doubled “k” consonant and the terminal “n”. The “n” has the same length as any other syllable. ryo te “Same”. Remember the “a” flows into the “i”, but with as little sound modification as possible. “hanmi” ha n mi “Stance” (‘T’ profile). Notice the intermediate “n”. It forms a syllable length element in its own right rather than simply terminating the “ha”. Pitfalls And Other Traps This guide is not a comprehensive etymology and analysis of the Japanese spoken language. Many things are beyond its scope and are best learned properly. The user should pick out the bits they feel is appropriate for what they want, or read the whole whale sized thing at their pleasure. If you want to really get to grips with Japanese “as she is spoke”, learn the language formally or consult a good textbook. In the meantime here are a few points you should be aware of, and why you may find yourselves embarrassed when you think you are saying something perfectly correctly. 2.6.1. Pitch Versus Stress Many European languages and English in particular convey additional meaning by using “stress”. Stress is the dynamic emphasis on a word or part of a word to enhance or change its meaning. It can be as crude as ironic tone for a whole sentence... “Oh! Yes. He really meant it” ... meaning of course the exact opposite; or it can be more subtle... “She really doesn’t want to do it.” ... Here the stress on “really” indicates to the hearer the extremity of the subjects dislike. Japanese doesn’t tend to use stress (except in the crude sense - a very loud sharp “Stop!” to reinforce the command), but rather alters the pitch of words and syllables. Here the tone of A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h V1.3 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10 Reference the syllables varies and sometimes this can be crucial. It can even lead to apparently the same word having two totally different spoken meanings. For example:“Hana”. If said with a rise in pitch on the last syllable (“n”) you have “flower”. With a flat pitch all the way you have “nose”. When written properly there is no problem in distinguishing these, they have completely different Chinese derived symbols, but neither Hiragana, Katakana nor Romaji can distinguish this. 2.6.2. Colloquial And Traditional Meanings Added To Concepts Much of Japanese is coloured with shades of meaning. This is shown by the several and often philosophical meanings embedded in the Chinese symbols used in written Japanese. Often this can cause mistranslation into other languages. While not strictly anything to do with pronunciation it makes an important point about learning the language to use it properly. A classic example is the descriptive noun “kireina”. A straight translation will tell you that this means “clean”. However the word has very strong overtones of purity, spiritual cleanliness and similar concepts. As a result it is used to mean “beautiful”. This is more than just skin deep beauty, and is a polite and deeply expressed opinion, expressing that something is beautiful in all ways. To the Japanese cleanliness is literally next to Godliness. “Kireina onna no hito” “Kireina hana” A Guide To Pronouncin#2FA23.doc h beautiful (clean), pure, lovely woman. - beautiful (clean), perfect, exquisite flower (or nose if you’re not careful) V1.4 4-Oct-2002 Page: 10