Extra Hume Notes

advertisement

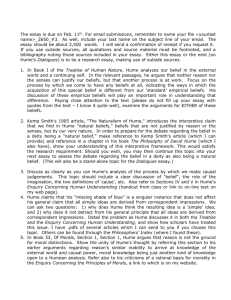

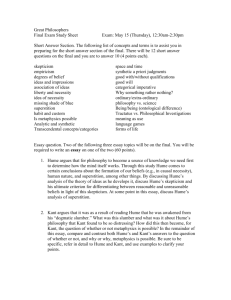

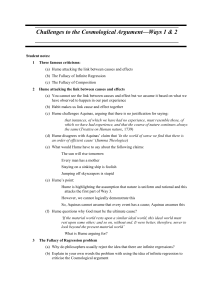

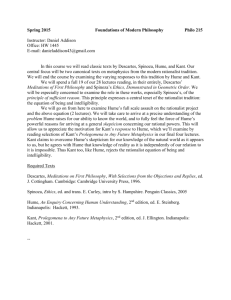

(See also PS2.5f., 113f. In course pack) Reminder: Study notes will go up this week Hume: 1. MBS: Make low-grade meat into sausage. Need to “hedge away” risk. If risk hedged away, = AAA bond (GNMA no longer exists) How do I hedge risk? Example: Fire, earthqakes Both can be done by examining past frequence Fires: Calculable, uncorrelated Eartquakes: Calculable, correlated Past frequency -> future frequency Why? Why do we believe that the past predicts the future? Are we justified in this belief? What happened? 2 types of risk insurance: Prepayment, default Irrational prepayment creates irrational option—in principle difficult, perhaps impossible. More like fire Default risk: in principle easy, but correlated Solution: Use the market itself (the market’s beliefs) to calculate the risk of correlation. Market collapses in the face of massive unhedged and correlated risk “Moral hazard”: Since lenders are borrowers are “disintermediated”, no one is manning the bridge Cf. http://archive.wired.com/techbiz/it/magazine/17-03/wp_quant "Correlation trading has spread through the psyche of the financial markets like a highly infectious thought virus," wrote derivatives guru Janet Tavakoli in 2006. 2. Induction in Aristotle When, if ever, are we justified in inferring from the past to the future Aristotle: See (Losee, pp. 6-7/coursepack 10) All these things (cows, horses, humans) are mammals. All these things have warm blood. All mammals have warm blood So long as: all these things mammals (“convertibility”: these things are—or stand in for—all the mammals) 3. Hume’s argument: Intro claim: All our reasoning about unknowns is based on causality. Example: Water on my kitchen floor. Am I indifferent? No! I want to know what caused it. Why? Because I don’t want it to happen again. I want to know: What was the prior event such that, if it hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have had water on my floor. I can, it seems, only work this out on the basis of past experience. Factors involved: I – Temporal priority II – Spatiotemporal Proximity (cf. Newton on gravitation) III – Constant conjunction Hume uses empiricist premise: we cannot know by merely by considering an object (1) what effects it will produce (2) what causes gave rise to it These can be known only by experience (iv.1, p. 324) But: it is one thing to say that 1. I have found that events of this kind (A) always give rise to events of this kind (B); and 2. I predict that A-events will be followed by B-events 1: looks backwards 2: looks forward Hume: “one may justly be inferred from the other” In fact: “it always is inferred” For us: process of induction He continues: “the connection between these propositions is not intuitive” “There is required a medium” (iv.2, p. 329) The rationalist opponent Rationalists like Leibniz believe that causal relations can be established by rational investigations Physics - once again - is a kind of geometry But empiricists deny this: “…knowledge of this relation [cause-and-effect] is not ... attained by reasonings a priori; but arises entirely from experience …” (iv.1, p. 324) Empiricist’s hope So if knowledge of causes is not attainable by reason, then it should be by experience But that is just what Hume denies If he is right, then experience cannot justify our causal statements We speak of causes and effects without rational justification Repetition But: surely repetition of an experiment validates the inference. But consider the individual case. Can we identify the causal relation? No! So why would repeating the experiment change the facts? We can’t “see” the cause in the one case So why do 100 identical cases change our state of knowledge? Hume’s attack Hume: “this is the sum of all of our experimental conclusions:” “From causes which appear similar we expect similar effects.” (iv.2, p. 331) But: this is not a proposition based on reason There are plenty of single cases in which it is false There are lots of similar things (eggs) which produce distinct effects (tasty, rotten) Inductive justification of induction And we can’t justify it (“similar causes give rise to similar effects”) as inductively supported Hume: “It is impossible … that any arguments from experience can prove this resemblance of the past to the future; since all these arguments are founded on the supposition of that resemblance” The assumption that “similar causes will [continue to] give rise to similar effects” itself requires inductive support Hume’s “sceptical solution” Hume’s arguments raise an “asymmetry problem” What is the difference between a person who has had many experiences, and one who has not? (v.1, pp.335-336) “He immediately infers the existence of one object from the appearance of the other.” Hume’s “sceptical solution” “There is some principle which determines him to form such a conclusion. This principle is custom or habit.” (ibid.) What makes the cases of the experienced and inexperienced persons different is: The experienced one is naturally inclined to infer one thing [effect] from another [cause] So what is causality? Hume continues (v.2) with an analysis of “feelings” such as belief, which accompany our thoughts Some intensely felt ideas we believe And there are “laws” or “principles” of connection among beliefs E.g. resemblance, contiguity, causation These “carry” the mind from one belief to another (v.2, p. 342) Hume’s “sceptical solution” The process which carries our mind from belief in the effect to belief in the cause (or vice versa) parallels the “powers” in the world “Here, then, is a kind of pre-established harmony between the course of nature and the succession of our ideas …” (v.2, p. 345) Problem: If we take Hume at his word, then there is no reason to believe that successive evidence objectively increases the likelihood of future behaviour. All it does is increase our “degree of belief” But I don’t want to know that I believe, I want to know whether I should believe. Gaussian copula applied to CDOs : “When the price of a credit default swap goes up, that indicates that default risk has risen. Li's breakthrough was that instead of waiting to assemble enough historical data about actual defaults, which are rare in the real world, he used historical prices from the CDS market. It's hard to build a historical model to predict Alice's or Britney's behavior, but anybody could see whether the price of credit default swaps on Britney tended to move in the same direction as that on Alice. If it did, then there was a strong correlation between Alice's and Britney's default risks, as priced by the market. Li wrote a model that used price rather than real-world default data as a shortcut (making an implicit assumption that financial markets in general, and CDS markets in particular, can price default risk correctly)." http://archive.wired.com/techbiz/it/magazine/17-03/wp_quant?currentPage=all”