Hello, I`m Ron Strickland

advertisement

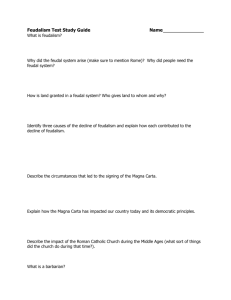

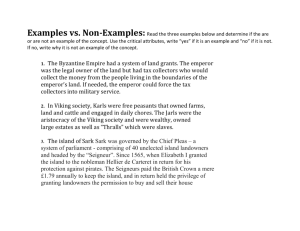

Hello, I’m Ron Strickland This webcast is one of a series in which I’m talking about the historical epoch of Modernity in Western civilization, and comparing different facets of modernity to conditions of Medieval European culture and society and to the emerging conditions of Postmodernity. NEXT SLIDE In another webcast I’ve spoken about the different economic systems in the three periods. NEXT SLIDE In this webcast, I’ll say some things about the dominant political systems of each period. Medieval feudalism was both an economic and a political system. As a political system, feudalism vested most political power in the elite class of aristocrats who owned the land. These feudal lords controlled “fiefs,” or manorial estates that were handed down from father to son from generation to generation. Feudal lords granted fiefs to “vassals,” who were then responsible for managing the land and making it productive. Peasants or serfs—poor people who worked the land—were considered to be bound to the land. The vassals and peasants were bound by obligations of fealty, or loyalty to the lords. Manorial political power was vested in the landlords, but vassals and peasants had certain rights that could not be breached. Vassals and peasants were obligated to follow the lords in combat; on the other hand, lords had a paternalistic responsibility toward all of the people in their domain. If a peasant grew ill or grew too old to work the land, the lord was responsible to provide food and shelter for the peasant nonetheless. NEXT SLIDE One distinctive feature of feudalism is that the unit of governmental power is relatively small—smaller than a nation-state. The terrirtories that would become England, France, Spain, etc., were governed regional aristocrats during the feudal epoch. Monarchs led loose confederations of aristocratic powers, but they did not have the kind of absolute control that they would later achieve during the early modern period. NEXT SLIDE Having said this, the feudal political system was more various and more complicated than I have suggested in this simple model. For example, in England there was parallel systems of secular and clerical governments. The Catholic Church was a government unto itself within the territory of England. And, in the late middle ages, successful merchants and craftsmen gained increased economic power and some degree of political independence in relation to the landed aristocracy. NEXT SLIDE During the early modern period, some Kings began to amass power at the expense of the aristocracy. This happened in both England and Spain, for example, in the latter half of the fifteenth century, and the power of the King in relation to the aristocracy continued to grow during the sixteenth century. There were some particular economic conditions that made this consolidation of national power both possible and necessary. For example, advances in navigational techniques made transatlantic sea voyages possible, but such expeditions required too much capital for any one aristocrat to well afford them. The development of the large scale power loom for weaving wool led to an export wool trade in England. Lands that had been devoted to crop production were shifted to grazing for sheep, encouraging a migration of peasants from farms to small urban centers where textile mills were set up. Thus was begun a long process of urbanization that would progressively erode the political and economic power of the aristocracy in relation to the monarch. NEXT SLIDE The rise of literacy also had the effect of facilitating the growing urbanization and international commerce, and Kings like Henry VII of England and Philip II of Spain developed elaborate bureaucratic apparatuses required to manage more concentrated urban populations and more extensive international commerce. NEXT SLIDE With the decline in power of the feudal lords, and the concentration of larger populations in cities, new political strategies were needed in order to govern. In addition to their expanded bureaucratic structures, absolute monarchs originally attempted to maintain ideological hegemony over their populations by invoking the ideology of divine right; the King ruled because he was ordained by God to rule, and to oppose his rule was to sin against God. NEXT SLIDE Soon enough this concept of divine right as the basis of royal power would begin to unravel. In 1648 the English people overthrow King Charles I, tried and convicted him of treason, and beheaded him. When, Charles Ist’s son, Charles II, took the throne in 1660, it was as a constitutional monarch in what would evolve into a bourgeois republic, with an increasingly large share of royal power ceded to parliament. NEXT SLIDE Bourgeois republics were to become the typical political regime of modernity, along with some notable experiments in socialism, and a fair share of totalitarian dictatorships. Though not all modern nation-states would evolve into republican-democratic forms of governments, there was in modernity a seemingly inevitable tendency toward more centralized governments, whether republican or totalitarian. NEXT SLIDE In postmodernity, there are some signs that the nation-state is in decline, or at least that the relationship between the democratic nation-state and its citizens is eroding as the resources of the state are harnessed to the interests of trans-national corporations and an elite class of wealthy oligarchs. An illustration—perhaps oversimplified--of this question might be seen in the debate about whether the war in Iraq is being fought for the protection of the American people or instead for protection of the interests of oil companies. NEXT SLIDE In any case, the war in Iraq offers a clear instance of another political development in postmodernity; that is, resources and functions that were previously governmental are now disinvested and outsourced to private contractors. So, in Iraq, combat support operations like food, shelter, transportation, communication and construction are being performed by Halliburton and other contractors, rather than by the U. S. military. Or, in another example, college students are now being required to pay higher tuition, and hence a larger share of the cost of their education than was the case at the height of the modern American nation-state. In this way the nation-state indirectly shifts the cost of human resource development, in the form of educating its citizens, from the public at larger to individual students as consumers. NEXT SLIDE Finally, there is an increased role for supra-national quasi-governmental organizations like the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. These organizations wield considerable power internationally, but they are not directly accountable to the voters of any country. Many observers argue that they are primarily accountable to the international business community, and only secondarily concerned with the welfare of ordinary people. During the sixteenth century the Catholic church’s control over the intellectual and social life of Europeans was shaken by the Protestant reformation and undermined by the spread of print and the rise of literacy. Platonic Idealism and Catholic Theism were challenged by a new philosophical system known as Rationalism. One of the key figures associated with Rationalism is the French philosopher Rene Descartes. Descartes was a devout Catholic who set out to develop a consistent philosophical response to the challenge of Protestantism. He began by rejecting everything that he could not be sure was true. The one thing that he could be absolutely sure about, he concluded, was that he existed, because he was thinking, and he could think unless he existed—hence his famous phrase, “Cogito ergo sum,” Latin for “I think, therefore I am.” For Descartes, this was proof of God’s existence, because any absolute truth—such as the fact of his existence—meant that something beyond human consciousness must exist. That something must be God. NEXT SLIDE But Rationalist thought would eventually evolve into a system that would question God’s existence, through the logical extension of the scientific method. The scientific method, originated by the English thinker Sir Francis Bacon, holds that knowledge of the real world can be built incrementally by scientists who observe and measure physical reality. Soon, this system would lead to kinds of knowledge that would challenge existing conceptions of reality, and thus threaten the Christian system of belief. One example of this Galileo’s theory of the heliocentric universe—the idea that the earth goes around the sun. When Galileo published this theory in the early seventeenth century, he was threatened with excommunication by the Catholic church, and he recanted his writings. NEXT SLIDE Related to the concept of Scientific method is another key philosophical movement of Modernity known as the “Enlightenment.” Enlightenment philosophers saw the religions thinkers of the medieval epoch as superstitious and ignorant, and they embraced rationalism and scientific thinking as the positive expression of human excellence and human achievement. In this way, it can be said that Enlightenment thinkers exalted the “human” to a level above “God”; they formulated a universal essence of “humanity” as a kind of absolute truth. NEXT SLIDE Modernity’s embrace of rationalism and the scientific method eventually led to an emphasis upon quantitative methods of knowing and statistical representations of reality. The difference between these ways of understanding reality and earlier, idealist paradigms can be seen in the development of modern research in genetic engineering, which is opposed by many people because it seems to suggests that humans could learn how to create life, and this is seen as something that threatens to diminish God’s power. The genetic code, in a sense “reduces” the biological essence of the human to a series of numbers. NEXT SLIDE I’ll conclude with some of the terms associated with the still-emerging paradigm of “postmodernity.” Postmodernity sees human existence and human understanding not as something that is informed or determined by an absolute or ideal truth, such as God, and not as something that is universal and essential to all humans but is produced by the rational thinking mind. NEXT SLIDE In fact, postmodernity rejects the concepts of absolute or essential reality. Instead, postmodernity sees human knowledge as based on “situated reality.” Human understanding is the product of social and material interactions. For the postmodern, we become human in our dealings with other people and in the processes of securing shelter and sustenance for life. Hence, the kinds of interactions we have and the kinds of lives we live, materially, determine what kind of people we will be. NEXT SLIDE Truth is therefore “contingent,” not absolute. Truth may change over time, and what it means to be human may change under different material and social circumstances. NEXT SLIDE I’ll conclude this webcast by showing you a couple of pictures that illustrate the difference between ways of understanding what it is to be human in the medieval period and in the modern period, respectively, and how a human social discourse like art can both express and help to produce these different ways of understanding. First, here is a painting of a market scene from the end of the fourteenth century. Notice that the scene includes big people and little people. The big people, in the steeple of a Church, are at the center of the scene. In front of the church there is a little person on a little horse, and some little sheep, I think, also in the foreground. And behind the church there are also some more little people. The size of the people in this painting corresponds to the social importance, the social power of the people being represented. The knowledge paradigm that informs this painting has little concern with our modern expectations of physical realism. NEXT SLIDE Now let’s look at another painting of a public scene from less than one hundred years later. This is one of the first paintings to employ the newly discovered technique of “perspective.” In this painting, there are small people and large people, but the large people are in the foreground and the small people are in the background.