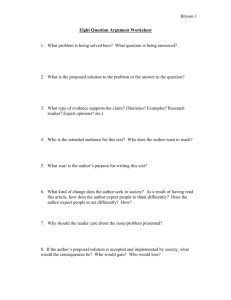

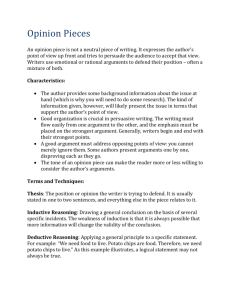

Modernism in the Twentieth Century

advertisement

Modernism in the Twentieth Century SS102 / Phil Harris Spring 2016 Writing a Term Paper 1. Choosing a paper topic is a tricky task, but since it must be done, it will be done. Here are a few guidelines to help your decision-making process along: • Make it interesting. You have most of the 20th century to choose from—why pick something that’s boring to you as a writer, and probably to me as a reader? If the facial hair of leading thinkers of the 20th century moves you, find a way to research it. If you’re fascinated by the development of consumer culture, why write about Sylvia Plath? Nothing reads more drearily than a paper you wrote at gunpoint, so find something that really appeals to you to write about. • Don’t just tell me what you already know. Find a subject you don’t know about, but would like to find out about. Here’s your chance to actually learn something you’ve wanted to know! Amazing! Don’t waste it by writing that same paper you always write about the development of bathtub submarine warfare. And I’d best not catch you using someone else’s paper, either… • Make sure there’s information available on your subject. After you settle on Jackson Pollock’s addiction to sugary breakfast cereals, make sure you can find some source books—and make sure they aren’t written in Swedish or Albanian. You gotta have a bibliography for this baby, and some of it has to consist of books whose pages you’ve actually flipped through. • Try to refrain from thinking Big Big Colossal. Remember that this is a finite (8-10 page) effort, so galactic-scale questions or musings are not going to work out well. “Reasons for Warfare in the Twentieth Century” or “Mass Entertainment, AZ” are probably a bit over the top. How about “The Military Buildup That Led to WWI”, or “Philo T. Farnsworth, Inventor of Television” instead? 2. Research is the next step. The OCAC library is affiliated with Washington County, and you all have WashCo library cards. Many of you probably live in Multnomah County, which means you’re eligible for a MultCo card as well. These are the golden keys to a universe of free source material. • If you’re not familiar with cruising the online catalogs at the libraries, get a librarian or a fellow student to show you how—it’s easy! It’s fun! It’s necessary! • Libraries will give you access not only to their own holdings, but also to books from around the region, even around the country, if you have the time it takes to obtain them. • Most books are easier to find if you know what are called “keywords”. Keywords are categories libraries use to make searching easier. Possible keywords might be “Military”, or “Fashion”, or “Furniture”. The more you can combine keywords, the more specific your search will be: “Military” is vast; “Armenian Military” is a lot more manageable. When you enter one or more of these words into the computer, lists of books will appear in the screen, and that’s a starting place. • Another handy way to narrow your search for material is to find a book or two that seem to talk about your interests, even if it’s just in one section or chapter. Almost every nonfiction book ever written has a bibliography at the end. Those bibliographies are great time-savers for you, because the author has already done a lot of legwork, finding books that may relate to your topic. Use them! • I require at least two book (non-magazine, non-website) sources for a paper. More sources are fine, but that’s my bottom line. This means that some subject matter may not work for this paper, especially if your prized choice is little known in the English-speaking world, or is still too early in their career for more than magazine articles to have been written about them or their work. For this reason, completely contemporary subject mater is tough to work with, at least for this class. •There’s always the librarian (all praise those saintly beings). 2a. We have a wonderful academic coach—make an appointment! She’s discreet, she can help you with any part or all of the process, and her services won’t cost you a dime. 3. Writing the damned thing is the final step: the sturm, the drang, the angst, the 104 cups of coffee, etc. Please don’t do permanent damage to yourself for the sake of a lousy grade; temporary derangement is completely acceptable, however. • Make notes as you read. Don’t be afraid to let what you read alter what you’re writing—your angle of view on your subject will probably change as you find more concrete information on your subject—hooray! That could be a sign that you’re learning something! Sometimes you’ll find that the subject isn’t as fascinating as you thought. If you start reading early enough in the term, you have the chance to make major course corrections. If you wait until the night before the paper is due, course changes are probably a bit touchier to make. So… • Pace yourself. Don’t leave everything (especially the reading and note-taking) till it’s very late in the term, especially if you know yourself well enough to foresee the train wreck before the train leaves the station. • Draw up an outline. This is the very best gift that uncounted generations of nerds have left for you as a legacy. An outline should function as a map to guide you through even the darkest, rainiest moments, the moments when your tires are spinning in hip-deep mud, the heater’s quit, and you’re about to run out of gas. A good outline is your signpost, your perspective in a cloudy world. It reminds you what the theme of your paper is. It tells you what’s a major point, what’s a minor one, and how to get from one to another. It leads you (and your eventual reader) on a treasure hunt, rather than a pub crawl. It feeds everything into your triumphant conclusion, instead of acquainting the reader with your disordered mind. It leaves your reader with a refreshing aftertaste, rather than a dead-mouse-in-the-mouth hangover. 4. When you actually write, there are a few simple methods that will smooth the path for both the producer and consumer of your paper. • Be concise. If a sentence is threatening to take over an entire page, draw your editing sword from its scabbard and hack it into two, or even three sentences. One thought, one sentence. • Be active. It’s always tempting to say “It is believed that…”, or “The window was opened by her…”. This hurts to read. How about “Robertson believes..” or “I believe…”? And “she opened the window” just lets in a breath of fresh air, doesn’t it? • Some busybody seems to have gone around to every seventh grade English class and told all the kids that “said” and “says” are swear words. So people write, “Charles Q. Sawhorse states, in his book, The Tragedy of Putty, that…”, or “it is written in the U.S. Constitution that…”. How about just saying and says-ing and saids-ing, instead? This is another way to make your paper more active, and so more lively to read. • Remember that when you’re writing a research paper, you’re marshaling facts and opinions to make some sort of argument. An argument is something that you believe, based on who you are and what you’ve read. Facts and factoids are great, but only if they serve the broader purpose of advancing your argument. Your argument is the very first thing in your outline, and it should be the very first thing in your paper, after whatever initial scene-setting you choose to do. By the end of the paper, you should feel convinced by your own argument. If you don’t buy your own thesis, why should I? • Leave yourself time to proofread, edit and rewrite. This is huge (“yuge”, if you’re from New Jersey). I can’t emphasize how important sleeping on a night’s writing can be. The next morning, for some reason, it’s always easier to spot the 36 times you used the word “overwhelming”, or the bibliography you forgot to write. Great writers aren’t born, or made, or hatched; they’re edited well. 5. Here are a few starter resources in the OCAC library. These are mostly style manuals. The titles are followed by library call numbers. William Zinsser On Writing Well PE1429 .Z5 1990 (reference) Scott Foresman Handbook for Writers PE1408 .H2968 1996 (reference) Checkett & Checkett The Write Start PE1048 .C444 2002 Kate Turabian A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses and Dissertations LB2369 .T8 1982 (reference) Theodore A. Rees Cheney Getting the Words Right: How to Revise, Edit & Rewrite PN187 .C54 1983 Natalie Goldberg Writing Down the Bones PN145 .C64 1986

![Program`s Dynamic Criteria Map (DCM)[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007112770_1-0a2faad44b8e94d6ea99c5f4cbf00e83-300x300.png)