A cross-linguistic comparison of competent word and nonword

advertisement

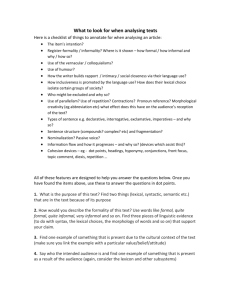

A cross-linguistic comparison of competent word and nonword reading: an illustration of the universality of cognitive processes in alphabetic languages1 Ângela M. V. Pinheiro Department of Psychology, Federal University of Minas Gerais, UFMG, Brazil ABSTRACT: Competent reading performance of 4th grade Scottish and Brazilian children was compared. The reading performance of the two samples was assessed by a word and nonword test (the words varied in levels of familiarity, regularity and length and the nonwords in length). The main objective of the work was the establishment of parameters of efficient reading performance which was taken as reference to the identification of areas of inefficiencies among Brazilian competent readers and also to compare the performance of these children with the performance of the English speaking counterparts to discover the aspects of the reading process that are common to the processing of information regardless of language differences, educational and social-cultural influences and the aspects that are orthography-specific. The main finding of this work is that the theory of English reading processes, can with few exceptions be applied to explain the reading processes in Portuguese. Competent reading in the two languages showed similarities in regard to time processing and error rates for the reading of words and nonwords and mainly differed in terms of the generality of the regularity effect and of the rate of letter processing for words and for nonwords. In Cognitive Psychology, the research in the study of the process of reading has been concentrated on two aspects: reading words in combination and reading isolated words. Research in the former has focussed on eye movements; the effects of sentence structure; context and text comprehension. On the other hand, investigation into the factors exerting influence on the processing of isolated words has focussed on reaction time measurement and analysis of error types produced by the reading of different classes of isolated words varying in levels of frequency of occurrence (familiar versus unfamiliar words), concreteness (concrete versus abstract words), regularity (regular versus irregular words (according to spelling-to-sound correspondence)) and lexicality (real words versus nonwords), for instance. To a great extent, the experimental work which has led to the formulation of models of reading (and spelling) has been based on the manipulation of the isolated words and nonwords. As Henderson (1984) puts it, “this apparently narrow concern with word recognition has turned out to raise a rich collection of questions about the reader´s access to phonology and meaning” (Henderson, 1984, p.1). Taking the word recognition theory as framework Seymour (1986) developed a method for the investigation of basic reading processes, which is referred to as the “Cognitive Assessment Procedure”. This method, which is appropriate for the assessment of both acquired and developmental reading disorders of English speakers (and also of Brazilian Portuguese speakers (e. g. Pinheiro, 1995, 1999 and Pinheiro & Parente, 1999)), presently, along with the Foundation Literacy Assessment (Seymour, 1997, 1999), constitutes a reference for the construction of a set of similar procedures in different alphabetic languages (Seymour and Ducan, 2000). It involves the use of (1) an information-processing model of basic reading functions and (2) tasks and factors which test the components of the model in 1 Parts of this paper has been published in Pinheiro (1999). order to determine the parts of the system that are damaged (acquired dyslexia) or failed to develop properly (developmental dyslexia) and also to analyse the remaining preserved or unaffected reading functions. This study describes the application of the tasks of reading aloud of Seymour’s (1986) cognitive analysis of competent and impaired reading performance to a sample of Brazilian children judged by their school teacher as having normal development in reading. Such analysis is based on the assumption that reading competence - the ability to read out single words and nonwords and show comprehension of the words - is the product of a set of underlying psychological processes. In the task of reading aloud (also referred to as vocalization task) - one of the tasks most commonly used to study reading - subjects are presented with either isolated words or nonwords on a computer screen and are asked to read them out aloud as rapidly and as accurately as possible. Reaction time and error levels are measured. Information-processing model and factors which test the components of the model In the dual-process model of visual word recognition and reading aloud (derived from Morton, 1979), one of the approaches developed to explain reading in an alphabetic script2, the reading system consists of a number of lexicons that contain lexical entries corresponding to both the orthographic (spelling) and phonological representation (pronunciation) of words and of two major processes (routes) for converting the words into sound: a lexical route and non-lexical route (also called phonological route). The lexical route is sub-divided into the lexical-semantic and the lexical-phonemic (or non-semantic) processes. Starting from the orthographic representation of the word, stored in a word recognition system (e.g. the visual (orthographic) input lexicon), in the lexicalsemantic process, the meaning of the word is first accessed and then its pronunciation is retrieved. In the lexical-phonemic process, on the other hand, the pronunciation of the word, stored in a word reproduction system (e.g. the speech (phonological) output lexicon) is addressed directly from its orthography without semantic mediation. While the lexical routes are used for fast recognition of familiar words, the non-lexical route, by the means of the application of grapheme-phoneme conversion (GPC) rules, allows the correct pronunciation of words whose spelling conform to these rules - regular words - , and also provide a regular pronunciation of nonwords (orthographically plausible, pronounceable letter strings with no meaning). Contemporary versions of this model are the theories developed by Ellis and Young (1988), Coltheart, Curtis, Atkins and Haller (1993) and Coltheart and Rastle (1994), among others. According to these accounts, both the linguistic characteristics of the written stimuli and the level of competence of the reader determine the type of process used. For example, regular words (according to letter-sound correspondences, as mentioned above) can be pronounced correctly by either the lexical processes or by the non-lexical process, but nonwords are mainly read by the latter process. That is: through the use of letter-sound correspondence rules. Reliance on the non-lexical process presents difficulties for the reading 2 The other approach in the study of reading is the Paralled-distributed-processing account (for a review of this work see Coltheart, et al (1993). of irregular words (the words that do not follow regular grapheme-phoneme correspondence rules), whose pronunciation, by violating such rules, would be assembled incorrectly, sometimes producing a ‘regularisation’ (e.g. canoe pronounced as ‘kanoh’). Alternatively, this process may result in a conflict of output phonologies - the correct pronunciation coming from the lexical process and the incorrect one from the phonological channel -, giving rise to a delay of reaction. Thus, the correct pronunciation of irregular words must be achieved by the lexical process, and a regularity effect - less accurate and/or slower reading of irregular words compared to the regular ones - is a sign of phonological reading, which implies that the operation of the lexical route can be supported by concurrent activity in the phonological route. Hence the occurrence of a ‘regularity effect’ will be taken as an indication that some grapheme-phoneme processing is involved in the retrieval of a response to a word. In regard to the recognition of words within the lexical process, those which occur more frequently in the written vocabulary - high-frequency words -, tend to be recognised more rapidly than the ones with lower occurrence - low-frequency words. This advantage in terms of processing for the former type of words is known as the frequency effect. While the locus of this frequency effect seems to be, according to Morton (1979) and Ellis (1985), in the visual input lexicon, Seymour (1987), extends its influence to the lexical routes, or as Ellis and Young (1988) suggest, to the operation of lexical retrieval within the speech output lexicon. The occurrence of a ‘word frequency effect’ is then taken as an indication of an involvement of the lexical process in reading aloud. Thus, the finding that different linguistic characteristics of the written stimuli engage different reading processes indicates that variables such as frequency of occurrence of words, spelling-to-sound regularity and lexicality (the distinction between real words and nonwords) are important means of informing how phonological and lexical processes manifest in reading. The manipulation of these psycholinguistic variables determines the availability or functional state of particular components of the reading model, which permits the assessment of the reading processes. Another important factor controlled in the task of reading aloud is the number of letters of the word and nonword stimuli - the length effect. This effect is obtained by relating reaction time to word and nonword length in order to find an index of processing rate (ms/letter). This measure is useful in assessing the mode of operation - serial or parallel - of both the visual input lexicon and the grapheme-phoneme conversion process. METHOD This is an individual case study which contrasts efficient and inefficient readers of the same school grade on the basis of their performance on the reading of isolated words and nonwords, and compares these groups of children with their English speaking counterpart Scottish children - tested by Seymour (1986). Previous research (Pinheiro, 1995) demonstrated that the dual-process model, developed in the context of the English language, can be extended to explain the reading processes in Portuguese and that the ‘cognitive assessment’ proposed by Seymour (in various publications starting from 1984) can be successfully applied to assess the reading capacities of Brazilian children. This study has as its main objective defining efficient reading performance and identifying areas of inefficiencies among Brazilian competent readers. Since in Brazil there are no standardised tests of reading/spelling achievement, it is expected that this study (and the ones mentioned above) can lay the foundations for the creation of an instrument for reading assessment which could be suitable for use by both researchers and applied practitioners. It is also expected that a comparison of the performance of English - and Portuguese speaking children on word and nonword reading might point to aspects of the reading process that are common to the two languages and to others that are orthography-specific. Sample. The sample consisted of the older subjects of Pinheiro's (1995) study - a group of 20 4th grade children of the primary sector from a high middle-class private school in Brazil. The selection criterion of the sample was the judgement of the reading ability of these subjects by their teacher. The mean age of the group was 10.8 years. The subjects were either average intelligence or above average. Procedure and apparatus. The reading assessment, administered using an PC, involved the reading aloud of two lists of words and two lists of nonwords, each containing 48 items. Stimuli were presented in lower case characters at the centre of an 18" CRT. A clock was used to control inter-stimulus intervals and to measure RT to the nearest millisecond. The word lists were based on an analysis of spelling-sound relationships in Portuguese orthography (Pinheiro, 1995) and also on an investigation of the frequency of occurrence of words in primary reading books (Pinheiro and Keys, 1987). The nonwords were formed with the same orthographic structure and length (4-7 letters) as the words used in the word lists. These experiments were all conducted by individual testing and were administered in two sessions. The first session started with a set of practice trials. The responses were classified as correct, incorrect or refused during the experiment by the experimenter and the incorrect responses were typed after their occurrence (An error classification was perfumed but it will not be reported here). RESULTS The results consisted of the correct vocal reaction time (RT) and of percentages of error responses obtained from the reading of word and nonword items separately. Individual ttests were then carried out on each subject to compare two reaction time distributions to test for t effects and an effect was said to be present if such comparison yielded a value of t which was significant at p<0.05 or better. Thus, the statistical analyses performed consisted of a search for the ‘frequency, regularity’ and ‘length effects’ in the responses for words and a search for the length effect in the responses for nonwords. In addition, the comparison between the distributions of low frequency words and nonwords tested for the ‘lexicality effect’. The error analysis followed a similar pattern, but did not consider the effect of length. Chi-squared tests were used to assess frequencies of incorrect responses observed under the manipulation of the factors frequency, regularity and lexicality. If the chi-square value obtained exceeded p <0.05 then the effect on accuracy was said to be significant. Regardless of the type of error and the number of errors made per item, only one error was marked for that item. In order to assess the length effect in the reaction time results, the slope and a line of best fit (obtained by the least squares procedure) to the relation between reaction time and word length were calculated and a test for linearity of trend was applied. In the 1986 research Seymour tested a sample of 22 upper primary level readers (competent readers and children in need of remedial tuition in reading) and assessed each individual child on intelligence using an abbreviated version of the WISC-R, and on reading and writing using the Schonell graded word test. The reading attainment was taken as reference to the classification of competence: reading age at or in advance of chronological age pointed to ‘competent performance’ and reading age behind chronological age, on the other hand, pointed to ‘incompetent performance’. Thirteen children - aged between 10:9 and 12:3 years - satisfied this criterion and were therefore classified as ‘competent readers’: they were all in advance of their ages in reading and were also of above average verbal intelligence. The remaining nine subjects - aged between 10:5 and 12:7 - presented reading ages behind their chronological ages and as a result were classified as ‘impaired’ readers. In the study to be reported, reading competence will be defined in terms of the efficiency of the lexical process (Seymour found that readers defined as competent by Schonell graded test demonstrate efficient functioning in the lexical process). The performance of the lexical route to phonology is defined in terms of overall reaction time and accuracy levels exhibited in the reading of high and low frequency words and by the effects produced by the manipulation of this variable and others such as letter-sound regularity and word length. Well-formed distributions for word reading will then be taken as indicative of efficient processing and a decline of efficiency in the reading of these stimuli will be pointed by outlying responses and/or exaggerated frequency effect. General Results - Brazilian children A generally positive relationship was found between words and nonwords. The correlations between high frequency words and nonwords, and between low frequency words and nonwords were significant for both reading time and errors. Taking the efficiency of the lexical processes as indicative of competent reading, an examination of the individual reaction time distributions reveals that 65% (13 out of 20) of the subjects produced an efficient performance in the word reading task and the remaining seven subjects showed a level of inefficiency. These subjects will be referred to as ‘inefficient readers’ and the thirteen word competent readers as will be referred to as ‘efficient subjects’. Efficient subjects Reading aloud of words Distribution of vocal reaction times: All efficient subjects produced well-formed reaction time distributions containing no slow or outlying responses - type A distribution (distributions with large preponderance of fast reaction times (below 2000 ms) containing no slow or outlying responses) - for both high frequency and low frequency words which is indicative of efficient processing. The remaining cases either exhibited distributions within the range of 250-2000 ms but with elevated means or type A distributions for high frequency words and type B (distributions with preponderance of fast times combined with a tail of slower responses (one or more outlying responses)) for low frequency words. One subject produced type B distributions for words of both levels of frequency. The tendency to produce occasional slow responses in word reading - ‘morphemic effect’ - is indicative of a mild inefficiency of the operation of the lexical route to phonology. Frequency effect: Although the low frequency (LF) words were read less rapidly than the high frequency (HF) words by all subjects, this difference was significant only for six of the thirteen efficient subjects (frequency effect range = 32-112 ms, t range = 1.881-2.617, d.f. = 90-93, p<0.05 or better).Out of the latter subjects, three showed exaggerated frequency effect. Regularity effect: As expected the irregularity of spelling did not affect the reading of the efficient subjects. As for the inefficient readers, this regularity effect was significant for only two subjects and was restricted to processing time. Length effect: The processing rate values (slope of the regression of reaction time against word length in letters) obtained for high and low frequency words by the efficient subjects fell within a range of (-5)-57 ms/letter and (-34)-66 ms/letter respectively. Six out of the 13 efficient subjects showed a significant linear trend for the HF words (F = > 5.58, d.f. = 1,4546, p<0.01) and only two for the LF words (F = > 4,07, d.f. = 1,45-46, p<0.01). Reading aloud of nonwords The task of reading nonwords aloud is a test of the phonological process. All efficient subjects and the remaining ones showed a significant lexicality effect, with the nonwords read more slowly than both HF and LF words [(t range (for the difference between nonwords and LF words) = 1.683-7.628, d.f. =126-151, p<0.05)]. As expected the nonword distribution presented higher means and were more widely dispersed than the low frequency word distribution. The processing rate for words was smaller (in terms of milliseconds per letter) than the rate for nonwords. Length effect: The linear trend test was significant (F = > 3.28, d.f. 1,70-91 = p<0.01) for all subjects but two: an efficient reader and a special case. The range of the slop values for the efficient subjects was 18-71. All special cases subjects except two and all critical cases showed slop values outside this range. Summary Normally efficient reading: As verified by Seymour (1986), competent reading is characterised by well-formed reaction time distribution for words and nonwords with the times grouped at the fast end of the reaction time scale - Type A distribution. The nonwords tend to have wider dispersion than the distributions for words. Low frequency words are expected to be read less rapidly than the high frequency words and this frequency effect should be significant for a number of subjects. By the same token, a lexicality effect in reading time (but not in accuracy) is expected in the reading of all subjects. The processing rate per letter - length effect - for words tends to be smaller than the rate for nonwords. In words, in contrast to nonwords, this effect is not expected to be significant in the reading of a proportion of subjects. Contrary to Seymour’s finding among his sample, the spelling irregularity does not affect the reading of the competent Brazilian subjects. The estimation of the range of values for this data, based on the results obtained by the efficient subjects, is summarised in 1.2 in Table 1. Inclusion of the results of the special cases (but not of the critical cases) raised the time estimates of this data. These figures are taken as the limit of inefficiency - mild morphemic and phonological effects - which is compatible with normal standards (see 2.2 in table 2). Inefficient reading: The inefficient readers presented a phonological pattern where the nonlexical route is more impaired than the lexical: the low frequency words were read significantly more rapidly than nonwords. This lexicality effect ranged from 267 ms to 627 ms (t = > 4378 , d.f. =115-134, p<0.01). Only two subjects showed an effect of regularity in the reading of low frequency words but they all produced substantial numbers of nonword error responses to both word and nonword items and produced a number of errors, which points to the use of the phonological process. As demonstrated by Seymour, the inefficiency in this process does not always restrict its use in reading. In what refers to variations in the use of strategies between subjects - indicated by the presence or absence of statistically significant effects of processing such as frequency, regularity, length and lexicality effects - the results suggested that the competent readers differentiated one from another in relation to the following factors: (1) the involvement of the process of grapheme-phoneme conversion in the retrieval of words indicated by an exaggerated frequency effect (or absence of it) or to a lesser extent, the exhibition of a regularity effect in low frequency word reading; (2) the adoption of a serial procedure in the processing of words and/or nonwords indicated by a rate of processing per letter outside the normal range of scores and (4) an exaggerated lexicality effect. Efficient reading in English and Portuguese The Brazilian data replicate many of the findings for ‘efficient’ reading reported by Seymour (1986) in his study with Scottish children. Table 1 summarises the results of the competent Scottish and Brazilian readers whose performance in the word and nonword tasks was efficient. These subjects read the items from both the word and nonword lists rapidly and accurately. - Table 1 about here Table 2 presents the expected figures for competent word and nonword reading for both Scottish and Brazilian children, including the subjects of both groups presenting a level of inefficiency. - Table 2 about here - Considering the frequency effect, while this effect was significant for all English speaking subjects it was significant for only half of the Brazilian subjects. Given that the high and low frequency Portuguese words used in this experiment were taken from a word count derived from a sample of published language textbooks used in the syllabus of primary education of the state schools in Brazil (Pinheiro and Keys, 1977), the lack of significant differences between the reading (but not the spelling) of high and low frequency words by some of the Brazilian efficient subjects raises questions about the generality of this effect. It could be argued then that, in proficient reading in Portuguese, the frequency effect might be considered more as an individual effect that occurs for some cases but not others rather than a standard effect. However, considering the small size of the Scottish sample, it is of interest to analyse larger samples of English speaking children in order to verify the generality of the frequency effect in the English language. In fact, a preliminary analysis of data from a larger sample of Scottish children whose age range was 9:0-11:9 years, tested recently by Seymour, showed that the frequency effect for processing time was, as for Brazilian children, an effect that tended to appear in the reading of some subjects but not of all and that the number of subjects not showing such an effect increased as a result of age and experience. Thus, as children gain more experience with reading, the low frequency words become recognised more quickly and the frequency effect tends to diminish and may not occur in the reading of a number of subjects. Taking the regularity effect, while it was significant for all Scottish subjects but one, the reading of only two subjects of the Brazilian sample were affected by this variable. This is an important difference between the two alphabetic systems under consideration. In fact, in terms of grapheme-phoneme correspondence, Portuguese orthography is more regular than English. Unlike English, most irregular words can be pronounced following the GPC rules. Pinheiro (1989) found that it is mainly at the initial stages of the reading process, and in cases of delayed development, that the irregular words are less easily recognised than the regular ones and this effect was limited to the low frequency items and to reading. A final difference - the processing rate for words and nonwords presented wider ranges in the Brazilian sample. A similar trend was found for words but not for nonwords by Pinheiro (1989) in a pilot study. This study was carried out with a sample of 7 Brazilian subjects (5 postgraduate students, including a Portuguese-English bilingual reader and 2 individuals with complete secondary education). An analysis of the length effects produced by these subjects suggested a processing rate varying between (-6) and 52 ms/letter for words and between 13 and 111 ms/letter for nonwords. Other evidence for the difference in processing rates which might exist between Portuguese and English was given by the bilingual subject (LS) who in addition to a cognitive assessment in Portuguese, undertook an equivalent test in English. LS proved to be a proficient reader in both Portuguese and English. In these two languages LS’s mean RT for both word and nonword reading was related to length and presented a significant length effect. A comparison between his performance in both assessments shows that LS read the Portuguese experimental items faster and more accurately than the English equivalents. However, while LS’s average processing rates for words and nonwords in Portuguese were 52 ms/letter and 61ms/letter respectively, in English his processing rates were 26ms/letter for words and 82ms/letter for nonwords. LS’s word and nonword reading was, therefore, affected by length in both languages but this effect was stronger in Portuguese than in English. In addition, given that all but one subject of Pinheiro’s pilot study were adults and that all of them proved to be competent readers, the range of their processing rates per letter was also high in comparison to that shown by Seymour’s (1986) subjects. According to Seymour the size of the length effect on reading reaction time is indicative of the nature of the processing for words and nonwords: in words, the absence of strong effects of length is an index of an approximation to a visual parallel process and in nonwords, larger effects than the ones for words are an index of a fast serial process. Thus, within-range, processing rate per letter is a measure of parallel process for words and of serial processing for nonwords. In sum, the regularity of spelling and the length effect affect competent reading in the two languages in a different manner. The implications of these differences for the Portuguese orthography are that the absence of a regularity effect cannot be taken as indicative of use of the lexical process and that wider ranges of processing rate for both words and nonwords may be expected in Brazilian children. DISCUSSION Using Seymour’s “Cognitive Assessment Procedure” of reading processes, the main objective of this work was the establishment of parameters of efficient reading performance which was taken as reference to the identification of areas of inefficiencies among Brazilian competent readers and also to compare the performance of these children with the performance of the English speaking counterparts to discover the aspects of the reading process that are common to the processing of information regardless of language differences, educational and social-cultural influences and the aspects that are orthography-specific. Starting from the last point, the main finding of this work and previous one (Pinheiro, 1995) is that the theory of English reading processes, can with few exceptions (one of them, the minor impact of the manipulation of letter-sound regularity, and possibly the expectation of larger processing rates for words), be applied to explain the reading processes in Portuguese. The present description of reading performance of the competent subjects reinforces Seymour’s finding that the normal readers do not form a heterogeneous group. As the competent Scottish readers, the Brazilians showed localised inefficiencies: some affected the speed of functioning of both lexical and non-lexical routes (slowness in words and nonwords reading); others were restricted to the non-lexical process. In the latter condition, there were instances in which the inefficiency was found only in terms of processing or in terms of both processing and accuracy. No case of dysfunction localised in the accuracy of nonword or deficiencies limited only to time of processing of words as found in the Scottish subjects was observed within the Brazilians. However, it is possible that these configurations would emerge in a more representative Brazilian sample of normal readers. Meantime, the important point here is that the data provided by the two nationalities confirm Seymours’s (1987) conclusion that competent reading may be achieved despite loss of efficiency in both the lexical and non-lexical processes. The analysis reported here not only shows the wide applicability of the assessment procedures developed by Seymour that can successfully be used to assess the reading performance of English and Portuguese speaking children, but also illustrates the great potential of these procedures for use by both researchers and applied practitioners. To conclude, the English-Portuguese comparison attempted is the beginning of a discussion about the universality of mental processing in reading in which the study of a variety of alphabetic systems has led to the consideration of which aspects of reading may be common to the processing of information and which are specific to a type of orthography, or even, to method of teaching. In fact, this is the main concern of a European network of research into reading acquisition and the origins of dyslexia in the European languages, (including the Portuguese), recently formed, and founded by the EC COST organisation (Action A8) (Seymour and Duncan, 2000). REFERENCES Coltheart, M., Curtis, B, Atkins, P. & Haller, M. (1993). Models of reading aloud: Dual-route and paralled-distributed-processing approaches. Psychological Review, 100, 589-608. Coltheart M. and Rastle, K. (1994). Serial processing in reading aloud: evidence for dualroute models of reading. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20, 1197-1211. Ellis, A. W. (1985). The cognitive neuropsychology of developmental (and acquired) dyslexia: A critical survey. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 2: 169-205. Ellis, A & Young, A. W. (1988). Human Cognitive Neuropsychology, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Henderson, L. (1984). Orthographies and reading: prespectives from cognitive psychology. Neuropsychology and linguistics. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Morton, J. (1979). Facilitation in word recognition: Experiments causing change in the logogen model. In P. A. Kolers, M. E. Wrolstad, and H. Bouma (ed.), Processing of visible language, Vol.1, (pp. 259-268). New York.: Plenum Press. Pinheiro, A. M. V. (1995). Reading and spelling development in Brazilian Portuguese. Reading & Writing, 7: 111-138. Pinheiro, A. M. V. (1999). Cognitive assessment of competent and impaired reading in Scottish and Brazilian children. Reading & Writing, 11/3 junho., 175-211. Pinheiro, A. M. V. & Keys, K. J. (1987). A word frequency count in Brazilian Portuguese. Unpublished work. Pinheiro, A. M. V. & Parente, M. A. M. P. (1999). Estudo de caso de um paciente com dislexia periférica e as implicações dessa condição nos processamentos centrais. Prófono: Revista de Atualização Científica. 11/1 março, 115-123, 1999. Schonell, G. B., & Schonell, F. E. (1956). Diagnostic and attainment testing. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. Seymour, P.H.K. (1986). Cognitive analysis of dyslexia. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Seymour, P.H.K. (1987). Individual cognitive analysis of competent and impaired reading. British Journal of Psychology, 78: 483-506. Seymour, P.H.K. (1997). Foundation of orthographic development. In C. Perfetti, L. Rieben, & M. Favol (Eds.), Learning to Spell. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum. Seymour, P.H.K. (1999). Cognitive architecture of early reading. In I. Lundberg, F. E. Tonnessen, & I. Austad (Eds.) Dyslexia: Advances in Theory and Practice. Dordrecht: Kluwer. Seymour, P.H.K and Duncan, L. G. (2000). Research Proposal: Foundadion Literacy Acquisition in European Languages. Table 1. Summary of estimates of the expected figures for word and nonword reading in English and Portuguese based on the results obtained by the efficient Scottish (1.1) and Brazilian (1.2) subjects. (a) Range of mean correct RT (ms), standard deviation and error rate (per cent) for the reading of high-frequency (HF) words, low-frequency (LF) words and nonwords, frequency effect and lexicality effect and (b) effect of word and nonword length. ___________________________________________________________________________ 1.1 Scottish subjects (total number = 13) Efficient word readers Efficient nonword readers (10 = 76.92 %) (7 = 53.85 %) _________________________________________________________ HF words LF words Frequency Nonword Lexicality Effect Effect (a) Range RT SD Error (%) 570-760 70-210 0-4 (b) Length Effect Processing rates ranges (ms/letter) 610-820 70-320 2-10 (-1)-23 30-100 6-33 780-1000 140-740 1-16 110-220 28-42 _____________________________________________________________________________ 1.2 Brazilian subjects (total number = 20) Efficient word readers Efficient nonword readers (13 = 65 %) (8 = 40 %) _________________________________________________________ HF words LF words Frequency Nonword Lexicality Effect Effect (a) Range RT SD Error (%) 560-840 80-290 0-4 (b) Length Effect Processing rates ranges (ms/letter) 1-60 590-870 80-300 2-6 1-70 20-95 650-1000 110-220 1-17* 40-250 20-70 __________________________________________________________________________ * In estimating the upper limit for error rate of nonword reading at about 17 per cent, the results of HSS was disregarded. HSS’s error rate was well clear of all other subjects showing a mild phonological effect. Table 2. The summary of the results obtained by the competent Scottish (2.1) and Brazilian (2.2) subjects that presented mild lexical and phonological effects. ________________________________________________________________________________________ HF words LF words Frequency Effect* Nonword Lexicality Effect** __________________________________________________________________________ 2.1 Scottish Sample Range RT 760-1000 SD 210-400 Slope 31-48 Error (%) 0-4 820-1200 320-600 13-35 2-10 100-200 1100-1300 480-570 500-1000 48-107 1-16 2.2 Brazilian Sample Range RT 840-1000 870-1100 47-150 1100-1500 250-580 SD 208-240 270-300 320-760 Slope 13-78 1-57 62-228 Error (%) 0-4 0-6 3-13 ___________________________________________________________________________ *, ** Seymour (1986) p. 53 e 55 respectively.