lab sheet

advertisement

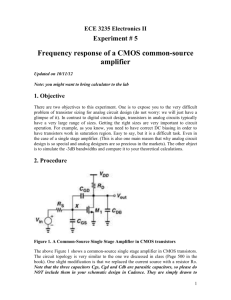

FACULTY OF ENGINEERING LAB SHEET EEE3096 COMMUNICATIONS ELECTRONICS TRIMESTER 1 (2015/2016) Experiment 1: CE 1 Design of RF Class-A Tuned Amplifier Experiment 2: CE 2 Design of Phase-Locked Loop Note : Students are advised to read through this lab sheet before doing experiment. 1 LAB Sheet CE1: Design of RF Class-A Tuned Amplifier 1.0 Objective There are many types of RF amplifier configuration using bipolar junction transistor. The Class-A amplifier is the most general. This experiment is designed to familiarize the student to the practical aspects of the design of a Class-A Tuned Amplifier. Issues such as the choice of components, the biasing requirement and prediction of the circuit performance will be illustrated. 2.0 Equipment Required 1. Function generator. 2. 100MHz bandwidth dual channel oscilloscope. 3. 5V power supplies. 4. A piece of breadboard and some single core wires. 5. A digital multi-meter. 2.1 Components Required (Quantities shown within parenthesis) 1. Resistors – 10K (1), 4.7K (1), 1K (1), 3.3K (1), 150 (1) and 470 (1). 2. Capacitors – 0.1uF (3), 1uF (1) and 100pF(1). 3. NPN Transistor – 2N3904. 4. Inductor – 4.7uH. 3.0 Introduction An amplifier is a circuit that provides an output signal that is an enlarged replica of the input. They faithfully reproduce input at a higher power level. An amplifier is classified according to how it is biased. A Class-A transistor amplifier is biased so that the transistor conducts continuously. The transistor of the Class-A amplifier is biased in the active region during the whole duration of operation. The operation of a transistor in active region is almost linear, thus the Class-A amplifier is a linear amplifier. Figure 1A and 1B shows two types of Class-A transistor amplifier circuits – the tuned and un-tuned amplifier. Figure. 1A Un-tuned Class A amplifier Figure. 1B Tuned Class A amplifier 2 3.1 Difference between Tuned and Un-tuned Class-A Amplifier An un-tuned amplifier has a wider bandwidth than a tuned amplifier. This means an untuned amplifier will enlarge an input signal for a wider range of frequencies. This is illustrated in Figure 2 for the comparison of the amplifier voltage gain. Figure 2 – Typical frequency response of tuned and un-tuned amplifier. To implement a tuned amplifier, a resonance network such as the parallel RLC tank network is used. Such a network has high impedance at the vicinity of the resonance frequency. The voltage gain of an amplifier is dependent on its load impedance. If the parallel RLC tank network is used as the load impedance, the gain of the amplifier will be very high when the input signal frequency is near the RLC network resonance frequency fo. At other frequencies, the RLC tank network has low impedance, thus forcing the amplifier to have low voltage gain. Figure 3 – Parallel RLC tank network. The bandwidth of a tuned amplifier using the parallel RLC tank network invariably depends on the bandwidth of the network. The bandwidth of the parallel RLC tank network in turn depends on its parallel resistance R. The higher the value of R the more narrow the bandwith (as illustrated in figure 4). This means the amplifier will become less sensitive at other frequencies. The bandwidth of a tuned circuit such as the parallel RLC network is defined as the amount of frequency deviation from the resonance frequency fo where the power delivered to the circuit is one-half that delivered at resonance. It can be shown from equation (1) and (2) that: 3 Q is known as the quality factor of the parallel RLC network. We observe that the higher the Q of a tuned network, the smaller will be the bandwidth. A high Q tuned network is synonymous with low loss. In the case of the parallel RLC network, the larger the value of R, the smaller the loss and hence a higher Q is obtained. Figure 4 – Frequency response of the RLC tank network with different value of R. 3.2 RF Amplifier Design Considerations Great care must be taken in designing an amplifier that could function properly in the megahertz range. The frequencies between 1MHz to 300MHz are collectively known as radio frequency (RF). Frequencies higher than 300MHz are categorized as microwave frequency (MF). An RF amplifier is an amplifier that would work well into the radio frequency region. RF amplifier is difficult to design, as most of the components will not approach their ideal characteristics at radio frequency. A number of considerations in designing an RF amplifier: Parasitic elements such as stray capacitance and inductance associated with the components. Parasitic elements exist for all practical components such as resistors, capacitors and inductors. It also exists between the conductors used to connect the components. The parasitic element of a practical transistor is illustrated in Figure 5. Stability of the amplifier. The parasitic inductance and capacitance associated with the components used to construct the amplifier will result in unwanted feedback. This could result in oscillation within the circuit, rendering the circuit useless. The characteristic of the transistor depends on operating frequency. Particularly the input impedance and the small signal current gain β of the transistor decreases 4 as the operating frequency is increased. This would decrease the overall gain of the circuit at radio frequency. This effect is evident for the un-tuned amplifier frequency response as shown in Figure 2. The drop in voltage gain as frequency is increased is due to the decrease in βof the transistor. Figure 5 – Parasitic elements associated with a practical transistor. 3.3 Transistor at High Frequencies At low frequencies, it is assumed that the transistor responds instantly to changes of input voltage or current. Actually, such is not the case, because the mechanism of the transport of charge carriers from Emitter to Collector is essentially one of diffusion. The commonemitter circuit is the most important practical configuration. Hence, we seek a CE model that will be valid at high frequencies. Such a circuit is called the hybrid-π, or the Giacoletto model, it is shown in Figure 6. The hybrid-π model gives a reasonable compromise between accuracy and simplicity up to microwave frequencies. A detailed explanation of the model can be found in Gray & Meyer, chapter 1, Millman & Halkias, chapter 11 or Collins, chapter 10. Figure 6 – The hybrid-π model for a transistor in CE configuration. 5 4.0 Tuned RF Class-A Amplifier Most RF Class-A amplifiers are of the tuned type. The reasons for using tuned amplifier are as follows: Higher voltage gain – The gain is dependent on the value of the load resistor and the collector biasing resistor. If we could increase the value of this resistance, higher gain would be obtained. However, by increasing the value of RC, we interfere with the biasing point of the transistor. If RC is too large, we might even bias the transistor into saturation. By using parallel RLC network, the transistor will see a large resistance of R at the resonance frequency while at dc the collector resistance is zero. Less susceptible to noise – If the gain of the amplifier is high, electrical noise in the input will be amplified to a perceptible level. A highly tuned amplifier will reject noise power that is not within its bandwidth. Since the noise power within the bandwidth is very small, a high signal-to-noise ratio at the output can be attained. Enable transformer coupling and impedance transformation – Sometimes the load can be coupled to the amplifier through mutual inductance. Thus, the inductor L in the RLC network can be magnetically coupled to another inductor, forming a transformer. The transformer has the advantage of being able to reflect a low impedance load into a high impedance value at the RLC network. Usually transformer-coupling circuit is used to cascade two single stage amplifiers together to obtain larger gain. At radio frequency, the input impedance of the transistor is small due to Ce and CC in the hybrid-π model of the transistor. Thus, a transformer is used to reflect the small input impedance of the second stage into large impedance at the output of the first stage. Analysis of tuned RF amplifier proceeds in the sequence as in the analysis for unturned amplifier. Instead of using RL for the load, the load is complex by virtue of the load inductor and load capacitor. Figure 7 – Using transformer to connect two single stage amplifiers together. 6 In particular, at resonance, the complex load will become real. For instance the impedance of the parallel RLC network becomes R at resonance f = fo. The voltage gain for the tuned amplifier at resonance is given by: 5.0 The Experiment Figure 8 – Class-A tuned transistor amplifier. 1. Connect the Class-A RF amplifier circuit as shown in Figure 8 using the prototype board (or breadboard as it is usually known among the electronic hobbyist community). 2. Be extra careful when building the circuit for high frequency operation. Keep the connecting wires on the prototype board as short as possible to reduce unwanted inductance and capacitance in your circuit. An example of the circuit construction is shown in Figure 9. Note the pin assignment on the general purpose NPN switching transistor 2N3904 in Figure 9. DC biasing measurement [15 marks] 3. Temporarily remove the transistor from the prototype board. Use the digital multimeter to measure the exact resistance of RB1 and RB2. Reinsert the transistor after the resistance measurement is done. Calculate the voltage at the base of the transistor 7 using the resistive voltage divider formula . Then calculate the voltage at the emitter of the transistor VE using VE=VB-0.7. 4. Connect the circuit to a 5V-power supply. Do not connect the function generator to the input yet. Measure the voltages at VC , VB and VE at C, B, E pins of the transistor using the digital multi-meter. Figure 9 – Photograph of the experiment setup. 5. Verify that VB-VE ≈ 0.7V. 8 6. Check if the calculated and measured VB and VE agree. If the values do not agree, can you explain why? 7. Estimate IC using . 8. Evaluate the transconductance gm of the transistor at T=25°C using AC Measurement [15 marks] 9. Now connect the function generator to the input of the circuit as shown in Figure 9. Set the function generator to output a sine wave at a frequency of about 5MHz. 10. . Set the oscilloscope to dual trace mode. Using Channel 2 of the oscilloscope, probe the base of the transistor. Using Channel 1of the oscilloscope, probe the load resistor RL as shown in Figure 10. Set the trigger of the scope to internal, with the triggering signal from Channel 1. Adjust the trigger level on the oscilloscope to obtain a stable waveform. Also, adjust the vertical scale and horizontal scale of the oscilloscope to obtain the waveform as in Figure 11. 11. Place a 3.3k ohm resistor at Point X. Adjust the output level of the function generator so that the peak-to-peak voltage swing is approximately 36mV or ΔVB = ±18mV. You would have to use the built-in attenuator of the function generator. Select attenuation of –20dB. Actually, we should keep the peak-to-peak voltage below 30mV. This will result in almost perfect sine wave obtained at the output (no harmonic distortion). However, for the current setup, large amount of noise is observed for signal voltage below 30mV, hence the compromise of 36mV. Figure 10 – Probing locations on the circuit. 9 12. Now sweep the frequency of the function generator from 1MHz to 10MHz. Record the peak-to-peak voltage at the input (Channel 2) and output (Channel 1) and determine the magnitude of the voltage gain AV as a function of frequency. Figure 11 – Sample waveforms as observed on Channel 1 and Channel 2 of the oscilloscope. 13. Plot a curve of AV versus frequency; estimate the resonance frequency of the amplifier from the curve. The input and output waveform should be approximately 180° out of phase during resonance. Furthermore the voltage gain AV is maximum when resonance occur, with the theoretical resonance frequency being approximated by equation (2), repeated here: The above equation is accurate if the series resistance of the inductor L is negligible, or the Q of the inductor is high. At L = 4.7μH, the series resistance of the inductor is small and hence can be omitted. 14. Practical Hints - Usually there will be a significant deviation of the calculated resonance frequency to the measured resonance frequency. This is due to stray capacitance between the transistor collector and ground/VCC rails on the prototype board and the tolerance of the inductor LC and capacitor CC. Acceptable resonance frequency is between 5.5MHz to 7.5MHz. Sketch the input and output waveform at resonance frequency on your lab report. 10 15. Use the digital multi-meter to measure the actual resistance of the load resistor R L. Substitute the value of RL, gm (calculated in 8.) and AV at resonance into equation (6) to estimate the value of rce. Ignore base spreading resistance rb’b. (7) 16. From the value of the estimated rce, find the Early voltage VA of the transistor 2N3904 using . Using the Hybrid-π parameters to Estimate Voltage Gain [15 marks] 17. Now change the load resistor RL to 470Ω. 18. Set the function generator output frequency at the resonance frequency measured earlier. Adjust the output level of the function generator so that VB peak-to-peak is approximately 36mV. 19. Measure VL peak-to-peak and determine the voltage gain of the circuit. 20. Measure the exact value of RL using the digital multi-meter. Using the value of rce, gm calculated earlier, determine the voltage gain of the amplifier using equation (6). Again, ignore the base spreading resistance rb’b. Compare the voltage gain AV obtained through measurement with the value obtained using equation (6). 21. Repeat 17. To 20. For RL=1470Ω. (1000Ω and 470Ω in series). Records the readings of VL, VB and AV at different RL(470Ω, 1000Ω, and 1470Ω) and comments. 11 22. Practical Hints - At radio frequencies above 10MHz, the typical voltage gain of a tuned Class A amplifier will be smaller than the value calculated using equation (6) due to reactance from capacitance Cc, Ce and stray capacitance between the leads of the transistor. Thus to have a reasonable gain at higher frequency, we could increase the value of RL, the parallel resistance of the RLC tank network or increase the transconductance gm. Usually RL is fixed, as it is the load resistor, the only recourse available is to increase gm. The gm can be increased by increasing the dc collector current IC. Hence, for this experiment you will notice that IC is in the range of 6-7mA. Typical IC for small signal amplifier is approximately 0.1-1mA. Usually in calculating the voltage gain of a transistor amplifier, rb’b and rce are ignored. The base spreading resistance rb’b is more or less independent of the transistor biasing and is small enough to be omitted for practical application. However, rce, which is due to Early effect, is inversely proportional to IC. For a transistor with VA = 30V, rce=30kΩ at IC=1mA and is big enough to be ignored. At IC=6mA, rce is only 5kΩ, its effect must be included in the AV formula of (6). The preceding steps illustrate a simple approach to estimating rce. 23. Finally, the circuit of Figure 8 using 2N3904 is capable of operating up to a frequency of 120MHz, although the effective voltage gain will drop to around -5. Maximum Output Swing of the Tuned Class-A Amplifier [15 marks] 24. Change the load resistor RL to 1kΩ again. Remove the 3.3k ohm resistor at Point X. Turn off the -20dB attenuation. With the function generator output frequency at the resonance frequency, slowly increase the output level of the function generator until the output voltage waveform is clipped at the lower level (Figure 12). Determine the maximum output voltage swing and the lower voltage threshold. 25. Compare the lower voltage threshold with the emitter voltage VE measured in the dc measurement. This level should be slightly above VE (about 0.1V-0.3V). The reason this clipping occurs is when VC (the transistor collector voltage) approaches VE, VCE is reduced. As VCE approaches 0V, the transistor shifts from forward active region to saturation region. When the transistor saturates the impedance between collector and emitter is low, thus the output voltage at collector is effectively shorted to the ground through the bypass capacitor CE (Figure 8). This results in the clipping of the output voltage. Figure 12 – Clipping at the output. 12 26. Therefore to allow maximum swing, the dc level VE of a Class A amplifier must be kept as low as possible, or alternatively a higher operating voltage can be used to shift the dc collector voltage higher. Discussion [40 marks]: 1) During DC biasing measurement, if CE changes from 0.1 µF to 1 µF, analyze the difference of the readings in VE (assume CE is ideal capacitor, no parasitic resistance or inductance)? 2) The input and output (VB and VL) waveform should be approximately 180° out of phase during resonance. Is VB leading VL or in the reverse way? Explain why. 3) Based on the information obtained in Step 21, evaluate the efficiency η of the Class A amplifier at RL= 470Ω, 1000Ω, and 1470Ω respectively. 4) Analyze the power dissipation PD effect of the Class A amplifier by comparing different values of RL= 470Ω, 1000Ω, and 1470Ω? Hints: 2 Po 1 VL ; Pdc Vcc I c ; Po ;VL is the peak AC output voltage PD Pdc Po 2 RL Pdc IMPORTNANT NOTE: Report submission: Submit your hand-written report within 10 days of performing the experiment to the same laboratory. Your report should include 1-2 pages of background information on RF Class-A amplifiers, with neat diagrams of circuits, waveforms, and data recorded. Include the discussion on the results obtained. References [1] P.R. Gray, R.G. Meyer, “ Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits “, 3rd edition, 1993. John-Wiley & Sons. [2] J. Millman , C.C. Halkias, “Integrated Electronics”, 1972, McGraw-Hill. [3] R.E. Collin, “Foundation for Microwave Engineering”, 1992, McGraw-Hill. [4] P.H. Young,”Electronic Communication Techniques”, 3rd edition, 1994, PrenticeHall International. 13 LAB Sheet CE2: Design of Phase Locked-Loop 1.0 Background The Phase-Locked Loop (PLL) was described for the synchronous reception of radio signals as far back as 1932 by H. de Bellescizi of France and has found use in numerous applications. Its widespread use today in all areas of electronics is due to the convenience and small size of the integrated circuit. A Phase-Locked Loop can generate, modulate, select, demodulate, and multiply signals. Instrumentation, television, space telemetry, and many other applications requiring a high degree of noise immunity and a narrow bandwidth use PLLs. PLLs are used in FM and AM demodulation because they do not require complex coil adjustments. PLLs are also used for frequency-shift keying (FSK) operations in digital communications. 2.0 Introduction A basic PLL consists of three basic components: 1. A phase detector. 2. Low pass filter 3. Voltage controlled oscillator (VCO) Sometimes an optional dc amplifier is connected between the output of the low pass filter and the input of the VCO to increase the dynamic range of the loop. A block diagram of the Phase-Locked Loop is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 – Essential components of a Phase-Locked Loop. • Phase detector - whose role is to allow the relative phase relationship of two inputs to be compared with each other. A larger phase difference produces a larger magnitude output. The phase detector is often implemented with a multiplier circuit, and the output is the product of the input signals. • Low pass filter (LPF) - to filter out the high frequency components of the multiplication output of the phase detector. The output of the filter is a dc voltage corresponding to the phase difference of the two-phase detector inputs. This dc voltage acts as the control voltage to the next element, the voltage controlled oscillator. The 14 PLL configuration may be designed so that it acts as a narrow band tracking filter when the LPF is a narrowband filter. In another mode of operation, the bandwidth of the LPF is wider so that the VCO can track the instantaneous frequency change of the input signal. • Voltage controlled oscillator - which has a natural, free running frequency when the applied control voltage is 0V (or some other nominal dc offset value), and whose frequency varies up and down around this free running frequency in proportion to the control voltage. In other words, the VCO is an oscillator that produces a periodic waveform, the frequency of which may be varied about some free running frequency, fFR, according to the value of the applied voltage. These three basic elements combine to form a powerful system in the PLL operation as follows: The input signal and the VCO signal are compared in the phase detector (multiplier), and the result is fed into low pass filter to produce a dc signal proportional to this phase difference. The difference between them represents the error between the two signals. The error signal controls the VCO frequency. If there is no error (the two signals are matched in phase), the VCO control voltage is 0 V (or at the nominal dc offset value) and the VCO frequency stays unchanged. If there is a difference, the error voltage is nonzero (or different than the nominal dc offset) and acts to cause the VCO output to change its phase and frequency so that it matches the input signal. The net effect is that this is a closed loop, negative feedback system that serves to compare the VCO constantly against the input signal and automatically correct the VCO phase for any difference between them. Phase-Locked The loop is said to be phase-locked when the VCO frequency fo and the input signal frequency fi are identical (fo = fi), and only a phase difference between the VCO and input signal exist. The concept of phase-locked is illustrated in Figure 2, where the first figure shows the VCO frequency fo not synchronized with the input frequency fi. The second shows the VCO output in synchrony with the input signal. fo=fi Figure 2 – Comparison between free-running and phase-locked condition. 15 Without an input signal the VCO is free-running at frequency fFR. When a signal arrives, the system enters into acquisition or capturing mode. After the PLL is phaselocked to the input signal, the VCO output will track any frequency changes of the input signal. This is called the tracking or locking mode. The sequence of acquisition and tracking is depicted in Figure 3. Figure 3 – Three sequences of PLL operation. Important Note that in Figure 2 and Figure 3, periodic sinusoidal signal is used for vo(t) and vi(t). Actually there is no restriction on the shape of vo(t) and vi(t), the Phase-Locked Loop should work with any periodic signals. In most cases the output of the VCO is a periodic square wave instead of a sinusoidal wave. 16 2.1 Capture and Lock Range For a practical PLL, there is a limited frequency range in which the loop can achieved phase-locked to an input signal from the free-running condition. This frequency range is known as the Capture Range. Upon achieving phase-locked, the VCO will track any changes in the input signal frequency. Again there is a limit to the frequency where the VCO can remain in synchronous with the input signal. This frequency range is known as the Lock Range. If the input signal’s frequency exceeds the Lock Range, the PLL will return to the initial free-running condition. Most of the time the Lock Range is greater than the Capture Range. Moreover the free-running frequency is usually at the center of the Capture and Lock Range. Figure 4 – Capture and Lock Range of a typical Phase-Locked Loop. 2.2 Application of Phase-Locked Loop • Synchronization of the horizontal and vertical scan in television receivers. Also for synchronization of the colour burst in a colour television receiver. • Spaceflight requirements inspired intensive application of phase-lock methods, where frequency drift, noise and Doppler frequency shift are prevalent. The PLL offers another key advantage: as a precise yet tunable filter. Using regular components, a traditional filter cannot achieve narrow bandwidth at high center frequencies: A 20 Hz bandwidth around 50 MHz is not realizable in practice. With a PLL, the center frequency is set by the VCO, while the low pass filter sets the bandwidth. These two are completely independent of each other, and a PLL can easily be designed for 20 Hz around 50 MHz (See Figure 5). For this reason the PLL is often used in recovering data from space probes, where extremely narrow bandwidths are used to minimize received noise, although the carrier may be at a high frequency. Finally, a change in one parameter is accomplished by changing only the VCO free running frequency, or the low pass filter bandwidth, without affecting the other parameter. • PLL can be used as a frequency demodulator. This is evident from Figure 3 where the output Vo changes with the input signal frequency. PLL is used as demodulator in Frequency Modulation (FM) and Frequency Shift Keying (FSK) systems. • Noisy oscillators can be enclosed in a PLL and locked to a clean signal. If the loop has a wide bandwidth, the oscillator tracks out its own noise and its output are greatly cleaned up. • Frequency synthesizer - Frequency multipliers and dividers can be built using PLLs as shown in Figure 6. 17 • Synchronization of digital transmission is typically obtained by phase-lock methods. Figure 5 – PLL realization of a bandpass filter, pass band of 20Hz and center frequency at 50MHz. Figure 6 – Frequency synthesizer using PLL. The Experiment Equipment Required 1. Dual channel oscilloscope. 2. Digital multi-meter. 3. Function generator. 4. A piece of breadboard and some single core wires 5. 74HC4046 IC (1 unit). 6. Ceramic type Capacitor(s) (50V): 1nF (3 units), 10nF (1 unit), 100nF (1 unit). 7. Electrolytic Capacitor (16V): 10uF (1 unit). 8. Resistor(s): 470R (1 unit), 3.3K(1 unit). Procedures Introduction In this simple exercise you would build a phase-locked loop (PLL) using the popular CMOS integrated circuit (IC) 74HC4046. This IC has a built-in relaxation voltage controlled oscillator (VCO) and three type of phase detectors (PD). This IC contains an 18 XOR gate PD, RS flip-flop PD and a PFD with charge pump. In this lab we would utilize the XOR gate PD and the PFD to built a PLL. The block diagram of the 74HC4046 is shown in Figure 7. Figure 7 – 74HC4046 block diagram Part 1: XOR Gate PLL Connect up the circuit as shown in Figure 8 on a project board. Be careful in handling the 74HC4046 IC as it is susceptible to electrostatic discharge damage. An example of the completed PLL is shown in Figure 9. 19 Figure 8 – PLL schematic using XOR gate PD Figure 9 – The hardware based on schematic of Figure 8 20 In this schematic, R2 and C4 determine the built-in VCO characteristics. These values allow the VCO oscillation frequency to vary from roughly 450 kHz to 3 MHz, for an input voltage of 0.5 V to 5V. Capacitor C3 serves to stabilize the potential on pin 12 of U1 (This pin is supposed to be left as open circuit). Pin 2 of U1 is the output of the XOR gate PD while pin 3 is the common input to all the internal PDs of the 74HC4046. Step 1 – Evaluate Measure the VCO gain [8 marks] Open the PLL loop by disconnecting pin 9 of U1. Power up the circuit with a power supply, setting the output voltage to around 5V. Connect pin 9 of U1 to a second power supply. Vary the second power supply output voltage from 0.5 V to 4.5 V in 0.5V step. Record the frequency observed from the VCO. Plot a graph relating the frequency of the VCO’s output versus VCO input. Calculate ko. A sample result is shown in Table 1. To evaluate: (i) Tabulate fvco versus Vo (ii) Draw a graph between Volts and fvco. (iii) Evaluate ko Step 2 – Connect signal generator – Phase locked [8 marks] Setup a signal generator to produce a 50% duty cycle square wave with peak-to-peak voltage of around 4.0 V and frequency of 1.5 MHz. Connect the output of the signal generator to pin 14 of U1 via C1. The PLL should immediately lock to the input signal. Observe the voltage Vo, Vin and Vvco during phase-locked. To evaluate: (i) Draw two waveforms: (i) Vo versus time and (ii) Vin versus time on same graph (ii) Draw two waveforms: (i) Vvco versus time and (ii) Vin versus time on same graph Step 3 – Tracking mode observation and hold-in range measurement [8 marks] Now you can increase and decrease the frequency of the input signal and watch the PLL tracks the input signal. Measure the lock or hold-in range (fH) of this PLL and compare this with theory. Step 4 – Static phase error measurement [8 marks] Set the input signal frequency to 1.0 MHz. From the waveforms, compute the difference between the excess phase of the input signal and the VCO, θe. The phase difference can be computed from the timing difference by (see Figure 5): (1) 21 Repeat this with other frequencies, for instance 750 kHz and 1.5 MHz. Check the values of θe obtained, average value of Vo (this can be obtained from pin 10 of U1) and VCO’s oscillating frequency all correlate well with theory. Step 5 – Determine the capture range [8 marks] Disconnect the signal generator from the PLL. Set its frequency to 450 kHz and connect it back to PLL. See if the PLL can lock to the input signal. Repeat this at 250 kHz step until you read 2.5 MHz. From this result we can estimate the capture of this PLL. Here it would be observed that the capture range for XOR gate PLL depends on the cut-off frequency of the RC filter. The lower the frequency, the smaller the capture range. You can verify this by changing C1 to 10 nF and repeat the above steps. Part 2: PFD with Charge Pump PLL [40 marks] Modify the circuit as in Figure 10. Here we are using the internal PFD with charge pump of 74HC4046. The loop filter is also modified accordingly to convert current into voltage. Figure 10 – PLL using PFD with charge pump Repeat Step 2 and Step 4 of Part 1 for this PLL. As an interesting experiment change C 2 to 1 nF afterwards, see if the PLL is stable. 22 To evaluate: [20 marks] (i) Evaluate the comparison of Vvco and Vin during phase-locked at 1.5 MHz by drawing their waveforms. (ii) Draw the voltage spikes at charge pump output during phase-locked at 1.5 MHz and explain the phenomenon. IMPORTNANT NOTE: Report submission: Submit your hand-written report within 10 days of performing the experiment to the same laboratory. Your report should include 1-2 pages of background information on Phase Locked-Loop, with neat diagrams of circuits, waveforms, and data recorded. Include the discussion on the results obtained. References [1] P.R. Gray, R.G. Meyer, “ Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits “, 3rd edition, 1993. John-Wiley & Sons. [2] J. Millman , C.C. Halkias, “Integrated Electronics”, 1972, McGraw-Hill. [3] R.E. Collin, “Foundation for Microwave Engineering”, 1992, McGraw-Hill. [4] P.H. Young,”Electronic Communication Techniques”, 3rd edition, 1994, PrenticeHall International. 23