5 - LVSC

Extracted from: Exploring Corporate Strategy, 6 th edition, Johnson & Scholes, Prentice-

Hall, 2002, pp230-238

5.5.5 The cultural web

Trying to understand the culture at all these levels is clearly important, but it is not straightforward. For example, it has already been noted that even when a strategy and the values of an organisation are written down, the underlying assumptions which make up the paradigm are usually only evident in the way in which people behave day-to-day.

To understand the taken-for-grantedness may mean being very sensitive to what is signified by the physical manifestations of culture evident in an organisation. Indeed, it is especially important to understand these wider aspects because not only do they give clues about the paradigm, but they are also likely to reinforce the assumptions within that paradigm. In effect, they are the representation in organisational action of what is taken-for-granted (ie they are also taken for granted). As mentioned in section 2.4.2, it is these taken-for-granted assumptions, that can result in strategic drift. The concept of the cultural web is a representation of the taken-for-granted assumptions, or paradigm, of an organisation and the physical manifestations of organisational culture (see exhibit 5.11). the cultural web can be used to understand culture in any of the frames of reference discussed above.

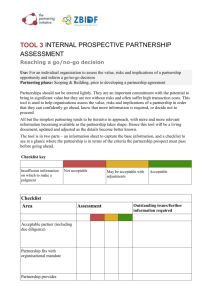

Exhibit 5.11

Culture can be analysed by observing the way in which the organisation (or organisational field or nation) actually behaves – the cultural artefacts (the routines, rituals, stories, structures, systems, etc). Out of these will also come the clues about the taken-for-granted assumptions. To use an analogy, it is like trying to describe an iceberg

(which is mainly submerged). This is done by observing the parts of the iceberg that show and also (from these clues) inferring what the submerged part of the iceberg must look like.

Illustration 5.8 shows a cultural web drawn up by trust managers in the National Health

Service in the UK. It would be similar to many other state-owned health care systems in

1

other countries. It should however be borne in mind that this is the view of managers; clinicians might well have quite different views.

Exhibit 5.12 outlines some of the questions that might help build up an understanding of culture through the elements of the cultural web:

The routine ways that members of the organisation behave towards each other, and towards those outside the organisation, make up ‘the way we do things around here’. At its best this lubricates the working of the organisation, and may provide distinctive and beneficial organisational competence. However, it can also represent a taken-for-grantedness about how things should happen which is extremely difficult to change and protective of core assumptions in the paradigm.

The rituals of the organisational life are the special events through which the organisations emphasises what is particularly important and reinforces ‘the way we do things around here’. Examples of ritual can include relatively formal organisational processes – training programmes, interview panels, promotion and assessment procedures, sales conference and so on. An extreme example, or course, is the ritualistic training of army recruits to prepare them for the discipline required in conflict. However, rituals can also be thought of as relatively informal processes such as drinks in the pub after work or gossiping around photocopying machines. A checklist of rituals is provided in Chapter 11 (see exhibit 11.7).

The stories told by members of the organisation to each other, to outsiders, to new recruits and so on, embed the present in its organisational history and also flag up important events and personalities. They typically have to do with successes, disasters, heroes, villains, and mavericks who deviate from the norm.

They distil the essence of the organisation’s past, legitimise types of behaviour and are devices for telling people what is important in the organisation.

Symbols such as logos, offices, cars and titles, or the type of language and terminology commonly used, become a shorthand representation of the nature of the organisation. For example, in long-established or conservative organisations it is likely that there will be many symbols of hierarchy or deference to do with formal office layout, differences in privilege between levels of management, the way in which people address each other, and so on. In turn this formalisation may reflect difficulties in changing strategies within a hierarchical or deferential system. The form of language used in an organisation can also be particularly revealing, especially with regard to customers or clients. For example, the head of a consumer protection agency in Australia described his clients as

‘complainers’, and in a major teaching hospital in the UK, consultants described patients as ‘clinical material’. Whilst such examples might be amusing, they reveal an underlying assumption about customers (or patients) which might play a significant role in influencing the strategy of an organisation.

Although symbols are shown separately in the cultural web, it should be remembered that many elements of the web are symbolic, in the sense that they convey messages beyond their functional purpose. Routines, control and reward

2

systems, and structures are symbolic in so far as they signal the type of behaviour valued in an organisation.

Power structures are also likely to be associated with key assumptions. The paradigm is, in some respects, the ‘formula for success’, which is taken for granted and likely to have grown up over the years,. The most powerful groupings within the organisation are likely to be closely associated with this set of core assumptions and beliefs.

For example, accountancy firms may now offer a whole range of services, but typically the most powerful individuals or groups have been qualified chartered accountants with a set of assumptions about the business and its market routed in audit practice. Power may be based not just on seniority. In some organisations, power could be lodged within other levels or functions: for example with technical experts in a high tech firm.

The control systems , measurements and reward systems emphasise what it is important to monitor within the organisation, and to focus attention and activity upon. For example, public service organisations have often been accused of being more concerned about stewardship of funds than with quality of service.

This is reflected in their procedures, which are more with accounting for spending than with regard for outputs. Reward systems are important influences on behaviours, but can also prove to be a barrier to success of new strategies. For example, an organisation with individually based bonus schemes related to volume could find it difficult to promote strategies requiring teamwork and an emphasis on quality rather than volume.

Organisational structure is likely to reflect power structures and, again, delineate important relationships and emphasise what is important in the organisation.

Formal hierarchical, mechanistic structures may emphasise that strategy is the province of top managers and everyone else is ‘working to orders’. Highly devolved structures (as discussed in Chapter 9) may signify that collaboration is less important that competition, and so on.

The paradigm of the organisation encapsulates and reinforces the behaviours observed in the other elements of the cultural web. The illustration shows that the overall picture of the NHS was of a system fundamentally about medical practice, fragmented in its power bases historically, with a division between clinical aspects of the organisation and its management; indeed, a system in which management had traditionally been seen as relatively trivial. As one executive put it: ‘there is an arrogance of clinicians, but it is a justifiable arrogance; after all, it is they who deliver on the shopfloor, not management’.

3

Exhibit 5.8

The cultural web of the NHS

The diagram shows a cultural web produced by managers in the NHS in the 1990s

Routines and rituals

This took form, for example, in routines of consultation and of prescribing drugs. Rituals had to do with what the managers termed “infantilising”, which “put patients in their place” – making them wait, putting them to bed, waking them up and so on. The subservience of patients was further emphasised by the elevation of clinicians with ritual consultation ceremonies and ward rounds. These are routines and rituals which emphasise that it is the professionals who are in control.

Stories

Most of the stories within health services concern developments in curing – particularly terminal illnesses. The heroes of the health service are in curing, not so much in caring.

There are also stories about villainous politicians trying to change the system, the failure of those who try to make changes and of heroic acts by those defending the system

(often well-known medical figures).

4

Symbols

Symbols reflected the various institutions within the organisation, with uniforms for clinical and nursing staff, distinct symbols for clinicians, such as their staff retinues, and status symbols such as mobile phones and dining rooms. The importance of the size and status of hospitals was reflected, not least, in the designation of “Royal” in the name, seen as a key means of ensuring that it might withstand the threat of closure.

Power structures

The power structure was fragmented between clinicians, nurses and managers.

However, historically, senior clinicians were the most powerful and managers had hitherto been seen as “administration”. As with many other organisations, there was also a strong informal network of individuals and groups that coalesced around specific issues to promote or resist a particular view.

Organisational structures

Structures were hierarchical and mechanistic. There was a clear pecking order between services, with the “caring” services low down the list – for example, mental health. At the informal level there was lots of “tribalism” between functions and professional groups.

Control systems

In hospitals the key measure has been “completed clinical episodes”, i.e. activity rather than results. Control over staff is exerted by senior professionals. Patronage is a key feature of this professional culture.

The paradigm

The assumptions which constitute the paradigm reflect the common public perception in the UK that the NHS is a “good thing”; a public service which should be provided equally, free of charge at the point of delivery. However, it is medical values that are central and the view that “medics know best”. This is an organisation concerned with curing illness rather than preventing illness in the first place. For example, pregnancy is not an illness, but pregnant women often argue that hospitals treat them as though they are ill. It is the acute sector within hospitals that is central to the service rather than, for example, care in the community. Overall, the NHS is seen as belonging to those who provide the service.

5

Exhibit 5.12

The cultural web: some useful questions

Stories

What core beliefs do stories reflect?

How pervasive are these beliefs (through levels)?

Do stories relate to:

Strengths or weaknesses?

Success or failures?

Conformity or mavericks?

Who are the heroes and villains?

What norms do the maverick depart from?

Routines and rituals

Which routines are emphasised?

Which would look odd if changed?

What behaviour do routines encourage?

What are the key rituals?

What core beliefs do they reflect?

What do training programmes emphasise?

How easy are routines/rituals to change?

Organisational structures

How mechanistic/organic are the structures?

How flat/hierarchical are the structures?

How formal/informal are the structures?

Do structures encourage collaboration or competition?

Which types of power structure do they support?

Control systems

What is most closely monitored/controlled?

Is emphasis on reward or punishment?

Are controls related to history or current strategies?

Are there many/few controls?

Power structures

What are the core beliefs of the leadership?

How strongly held are these beliefs (idealists or pragmatists)?

How is power distributed in the organisation?

What are the main blockages to change?

Symbols

What language and jargon are used?

How internal or accessible are they?

What aspects of strategy are highlighted in publicity?

What status symbols are there?

Are there particular symbols which denote the organisation?

Overall

What is the dominant culture?

How easy is this to change?

6

Exhibit 11.7

Organisational rituals

Types of ritual

Passage

Role

Enhancement

Consolidate and promote social roles and interaction

Recognise effort benefiting

Renewal organisation

Similarly motivate others

Reassure that something is being done

Focus attention on issues

Integration Encourage shared commitment

Reassert rightness of norms

Conflict reduction Reduce conflict and aggression

Degradation Publicly acknowledge problems

Dissolve/weaken social or political roles

Sense making

Challenge

Sharing of interpretations and sense making

‘Throwing down the gauntlet’

Examples

Induction programmes

Training programmes

Awards ceremonies

Promotions

Appointment of consultants

Project teams

Christmas parties

Negotiating committees

Firing top executives

Demotion or ‘passing over’

New CEO’s different behaviour

Grumbling

Working to rule

Counter-challenge Resistance to new ways of doing things

7

Exhibit 5.13

Characterising culture

Miles & Snow

Characteristics of strategic decision making

Type of culture Dominant objectives Preferred strategies

Defender

Prospector

Desire for a secure and stable niche in the market

Location and exploitation of new product and market opportunities

Specialisation; costefficient production; marketing emphasises price and service to defend current business; tendency to vertical integration

Growth through product and market development

(often in spurts); constant monitoring of environmental change; multiple technologies

Planning & control systems

Centralised, detailed control; emphasis on cost efficiency; extensive use of formal planning

Emphasis on flexibility; decentralised control; use of ad hoc measurements

Analyser Desire to match new ventures to present shape of business

Steady growth through market penetration, exploitation of applied research, followers in the

Very complicated; coordinating roles between functions (eg product managers); intensive market planning

Source: adapted from R E Miles and CC Snow, Organisational Strategy, Structure and Process, McGraw Hill, 1978

Handy

Characteristics

Type of culture Strategy driven by: Modus operandi Suited to deliver

Role Committees Structure and systems Efficiency

Repetitive tasks

Task Teams Shared values

Ad hoc procedures

Command

Projects or tasks

Innovation

Rapid response Power Leaders

Personal Individuals Personal creativity Innovation

Expert power

Source: adapted from C Handy, Understanding Organisations, 4 th edition, Penguin, 1993

8