Sociology 12 Unit 1 Application

advertisement

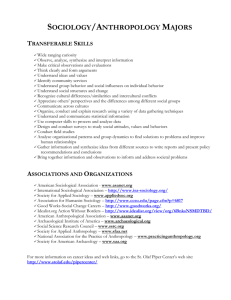

Sociology 12 Unit 1 Application The concept of the application section is to formatively evaluate your progress on outcomes. By completing these formative evaluations you will have a better grasp on the material as well as multiple opportunities to meet and exceed the outcomes. Please remember that if you have a grade on an evaluation that you would like to improve you have the opportunity to resubmit that evaluation and I will alter your grade accordingly. All formative assessments that are not completed on time will be referred for academic assistance and intervention. If you do not understand a concept or outcome it is your responsibility to make an appointment to see me. I am always available to help you I just need to know that you need the help. Unit 1 Outcomes: Discuss and evaluate the ideas, and theories of prominent social scientists Demonstrate an understanding of the different disciplines involved in the study of individuals and groups in society (sociology, psychology and anthropology) Demonstrate an understanding and appreciation of concepts and methods used in the social sciences. Apply social science methods to specific situations. Work co-operatively to apply these concepts and methods. Explore sources of bias, understand how to detect bias, explore personal bias and reflect on ways to reduce bias. Examine evidence using sociological methods of inquiry Application 1: What kind of social scientist are you? Outcomes: Apply social science methods to specific situations. Explore sources of bias, understand how to detect bias, explore personal bias and reflect on ways to reduce bias. Discuss and evaluate the ideas, and theories of prominent social scientists Demonstrate an understanding of the different disciplines involved in the study of individuals and groups in society (sociology, psychology and anthropology) Demonstrate an understanding and appreciation of concepts and methods used in the social sciences. Materials: Appendix A: Information Pack Appendix B: What Kind of Social Scientist are You? Appendix C: What Kind of Social Scientist are You? (Evaluation Sheet) Application: Have students review the information pack. Ask students to define the terms in the front of each section – they may highlight the terms or they may write them as a dictionary Give out What Kind of Social Scientist are You? Ask students to read the article. Discuss the article with students. Ask them for their input – what do they think? Give the Evaluation sheet for the exercise. Give 2 days for completion of this sheet. Application 2: Sociology V. Anthropology Outcomes covered: Discuss and evaluate the ideas, and theories of prominent social scientists Demonstrate an understanding of the different disciplines involved in the study of individuals and groups in society (sociology, psychology and anthropology) Demonstrate an understanding and appreciation of concepts and methods used in the social sciences. Materials: Appendix D: Sociology Article Appendix E: Anthropology Article Appendix F: Reflection and Consideration Application Session: Students may work in pairs but this is an individual effort. Hand out copies of both articles and then ask students to complete a Venn Diagram of Sociology and Anthropology. Remember a Venn Diagram consists of overlapping circles with space to write in each one. Have the students label one side Sociology and the other Anthropology. The middle section is to be left blank. On each one students are to write the key aspects of each one in the appropriate section and the common aspects in the centre. Give out the Reflection and Consideration sheet. Have students watch _________. The sheet is due the class after completion of the movie. After viewing the movie place a copy of the Reflection and Consideration sheet on the overhead as a transparency and derive indicators of mastery with the students. Lesson 4: Evaluation Unit 1 Outcomes Evaluated: Discuss and evaluate the ideas, and theories of prominent social scientists Demonstrate an understanding of the different disciplines involved in the study of individuals and groups in society (sociology, psychology and anthropology) Demonstrate an understanding and appreciation of concepts and methods used in the social sciences. Apply social science methods to specific situations. Work co-operatively to apply these concepts and methods. Explore sources of bias, understand how to detect bias, explore personal bias and reflect on ways to reduce bias. Examine evidence using sociological methods of inquiry Materials: Overhead & Markers Transparency of Appendix G Appendix G: Outcomes Unit 1 Evaluation: Begin with a quick write 5 minutes – What is the most intriguing thing we have learned so far? Have students complete a learning summary. Learning Summary: Give students Appendix F: Outcomes Unit 1 and complete with the students on the overhead. Ask students for each outcome what is expected to show mastery. A learning summary is 3-5 pages double spaced. Students are to take the outcomes and address each one in paragraph form. The concept is that they are to have a discussion with me on paper. They may use all of their notes and assessments to complete the summary. They should be directed to use their sheet Outcomes Unit 1. Students have one class in the classroom and one class in the computer lab. Evaluations are due within 5 days. (If assigned on a Monday get back on Friday or other reasonable time frame.) Remind students that if they have 5 days to complete it I have at least that long to get them back. Evaluation of their learning summaries will be based on the outcomes. Appendix A: Information Pack Who are Important Anthropologists? (Early Researchers) Who are Important Anthropologists? (Modern Researchers) Who are Important Sociologists? (Early Researchers) Who are Important Sociologists? (Modern Researchers) Who are Important Psychologists? (Early Researchers) Who are Important Psychologists? (Modern Researchers) All Articles are from: Bain, Colin, M; Colyer, Jill, S.; Newton, Acqueline; Hawes, Reg; Canadian Society: A Changing TapestryOxford University Press; Don Mills, ON; 1994. Appendix B: What Kind of Social Scientist are You? Taken From: Bain, Colin, M; Colyer, Jill, S.; Newton, Acqueline; Hawes, Reg; Canadian Society: A Changing TapestryOxford University Press; Don Mills, ON; 1994. Appendix C: What Kind of Social Scientist are You? Formative Assessment Outcomes Indicators of Mastery Apply social science methods to specific situations. Explore sources of bias, understand how to detect bias, explore personal bias and reflect on ways to reduce bias. Discuss and evaluate the ideas, and theories of prominent social scientists Demonstrate an understanding of the different disciplines involved in the study of individuals and groups in society (sociology, psychology and anthropology) Demonstrate an understanding and appreciation of concepts and methods used in the social sciences. 1-5 /25 Notes/Considerations: 1. Which of the three conference speakers most likely made the following statements. Explain the reasons for your choices. A. People become prostitutes because they want to be prostitutes. B. Women have fewer choices in society than men. C. In any social situation, what the participants feel is happening is more important than what any social scientists feel is happening. D. The law punishes the powerless more than the powerful. E. In prostitution the prostitute and the clients are not likely to attach their own importance to their actions. F. Prostitution benefits society. G. Prostitution victimizes the poor and unskilled. H. The key to understanding people’s actions is to study the person. I. Order and agreement are the natural order of society. J. Men as a group have more power in society than women. 2. How might each speaker explain each of the following situations? A. Why some people use and sell illegal drugs? B. Why some people constantly drive above the speed limit while others obey the law? C. Why some people in Canada are wealthy while others are poor? D. Why some people in Canada are polite while others are rude? E. Why some students work hard and always attend classes while others don’t study and skip? 3. In your opinion, which of the three theories best matches each of the statements in the first question? Is there any pattern to these answers? Does one theory tend to be the best explanation for the majority of the situations? What conclusions can you draw from this? 4. The current debate in the punishment of prostitutes and their clients is that harsh and public punishment is the only means to stop sex crimes. In several states and even in provinces the pictures of clients are published along with their names. If their car is used in the commission of the crime it is seized by the police and sold to fund rehabilitation programs. Jail time is guaranteed. TAKE A STANCE! Assign yourself a role as either a functionalist, a conflict theorist or a symbolic interactionist. What do you think? Why do you think that? Appendix D: Sociology Article From: Brock University Department of Sociology and Anthropology What is Sociology? Sociology, like the other social sciences, is interested in how, where, when and why people act out the events of their lives in the ways they do. The focus, however, is not on individual behaviour, as it tends to be in Psychology. Nor does sociology confine itself to specific kinds of human interaction, as do Economics and Political Science. Introductory textbooks stress sociology's focus on aggregates of people, and in practice the sociologist may be interested in everything from small group dynamics to large-scale global trends. Indeed, sociology can be seen as a kind of "umbrella" social science which addresses issues in politics, economics, history, anthropology, geography, social psychology, and culture, while highlighting their specifically social dimensions. Accordingly, sociology, as a discipline, is concerned with virtually every aspect of how human beings think and behave. Historically, sociology grew out of a mixture of European social philosophy, British liberalism and rationalism. Our field's founders believed that a scientific explanation of social behaviour and of the diversity of human experience could help remedy social problems, specifically those arising from the industrial revolution. To this end, they advocated a combination of social theorizing and empirical research. Today, sociologists promote a critical awareness and understanding of an extensive range of social issues and a wide array of social institutions; but theory and research methodology remain central to our enterprise. At the time when sociologists were first trying to lay claim to a discrete place in North American universities, they depicted sociology as a science which aspired to be as objective, and free of political implications, as physics or mathematics. We now understand that no science, and especially no social science, can claim to be completely impartial or free of social determinations. This does not excuse us from the obligation to seek out the facts and to subordinate our biases to the demands of an honest pursuit of objective knowledge. However, by giving up the pretence of a pristine, value-free objectivity (that is, the idea that sociologists can describe and analyze "what is" in society without being influenced by conceptions of what might be" or "what should be"), the discipline of sociology has been able to liberate itself to directly address social policy issues. Of course this means that sociologists do not always agree. Your course instructors will not always see eye-to-eye on issues and may approach the teaching of their courses from very different perspectives. What we do seem to agree upon, however, is that we would like to help make the world a better place. One of the main tasks of the Sociology major is to learn to think critically about social institutions and social problems. This is not only crucial for success in Sociology, it is also an important life skill. On the job, reading the newspapers, in conversation with friends, we are bombarded with "facts" about and interpretations of the social world in which we live. People who have acquired what C. Wright Mills called the "Sociological Imagination" are well equipped to put this information into a larger, historical context, as well as to relate it to their own lives and experiences: 2 “[The sociological imagination] is the capacity to shift from one perspective to another - from the political to the psychological; from examination of a single family to comparative assessment of the national budgets of the world; from the theological school to the military establishment; from considerations of an oil industry to studies of contemporary poetry. It is the capacity to range from the most impersonal and remote transformations to the most intimate features of the human self B and to see the relations between the two.” (Mills, 1959: 7) When planning the courses you will be taking in our department, you will have noticed that the required courses, aside from the introductory survey course, are all in social theory or research methods. Some students think these courses are not as "sexy" as other courses dealing with controversial topical issues or contemporary social institutions. However, theory and methods are fundamental to the development of the critical sociological mind. The social theory courses provide students with different frameworks for looking at our social world. Understanding theory, even the perspectives of thinkers who lived long ago, helps us understand the underlying approaches of contemporary authors, and gives clues to the potential implications of their work. For example, you might be reading a newspaper editorial or an article in a magazine on the changing demographics of Canada. The author expresses ominous concern over the declining birth rate among well-educated Canadian women. If you have studied Social Darwinism and know something about the eugenics movement that developed out of this theoretical framework, you will be able to see the larger picture surrounding the author's words. If you have also read feminist theory, it will not take you long to figure out the possible policy implications of the author's dire warnings. Taken to its extreme, the implied message behind the talk of declining fertility might be one of discouraging young women of certain social classes and racial groups from pursuing higher education! As for research methods, the more comfortable you are with them, the better prepared you will be to be a critical consumer of the "social facts" which bombard us in our everyday lives. It is a mistake to assume that because something appears in print, even in an academic journal, it must necessarily be well researched and well founded. In Sociology, it is not enough to simply report what others have said about a social problem or social issue. You must continually ask yourself if these "facts" are verifiable and if they are based on valid and reliable social research. For example, we are always hearing about "welfare cheaters," or reports of the dollar cost of "welfare fraud." By definition, people who cheat any system are a hidden population; if they identified themselves, they would be penalized. We have no way of accurately calculating their numbers. All we can rely on is anecdotal evidence of cases that have been uncovered. All attempts to quantify the size of a hidden population can only be estimates, and those who produce estimates will bid high or bid low, depending on a variety of personal or political propensities. Sociologists who understand research methods can effortlessly and automatically ask crucial questions about the social "facts" to which they are exposed. They think about uncontrolled or intervening variables, they wonder about how samples were assembled, they question whether observed differences are large enough to be meaningful, and so on. What you learn in your methods courses will be of lifetime benefit, even if you are never required to conduct a research project yourself. Appendix E: Anthropology Article Article from: The American Anthropological Association What is Anthropology? Are you as interested as I am in knowing how, when, and where human life arose, what the first human societies and languages were like, why cultures have evolved along diverse but often remarkably convergent pathways, why distinctions of rank came into being, and how small bands and villages gave way to chiefdoms and chiefdoms to mighty states and empires? --Marvin Harris, Our Kind Those words, written by the American anthropologist Marvin Harris, convey some of his fascination with the field of anthropology. But what is anthropology? Study of Humankind The word anthropology itself tells the basic story — from the Greek anthropos ("human") and logia ("study") — it is the study of humankind, from its beginnings millions of years ago to the present day. Nothing human is alien to anthropology. Indeed, of the many disciplines that study our species, Homo sapiens, only anthropology seeks to understand the whole panorama — in geographic space and evolutionary time — of human existence. Though easy to define, anthropology is difficult to describe. Its subject matter is both exotic (e.g., star lore of the Australian aborigines) and commonplace (anatomy of the foot). And its focus is both sweeping (the evolution of language) and microscopic (the use-wear of obsidian tools). Anthropologists may study ancient Mayan hieroglyphics, the music of African Pygmies, and the corporate culture of a U.S. car manufacturer. But always, the common goal links these vastly different projects: to advance knowledge of who we are, how we came to be that way — and where we may go in the future. I am a human, and nothing human can be of indifference to me. --Terence, The Self-Torturer Curiosity. In a sense, we all "do" anthropology because it is rooted in a universal human trait: curiosity. We are curious about ourselves and about other people, the living as well as the dead, here and around the globe. We ask anthropological questions: Do all societies have marriage customs? As a species, are human beings innately violent or peaceful? Did the earliest humans have light or dark skins? When did people first begin speaking a language? How related are humans, monkeys and chimpanzees? Is Homo sapiens's brain still evolving? Such questions are part of a folk anthropology practiced in school yards, office buildings and neighborhood cafes. But if we are all amateur anthropologists, what do the professionals study? How does the science of anthropology differ from ordinary opinion sharing and "common sense?" Comparative Method. As a discipline, anthropology begins with a simple yet powerful idea: any detail of our behavior can be understood better when it is seen against the backdrop of the full range of human behavior. This, the comparative method, attempts to explain similarities and differences among people holistically, in the context of humanity as a whole. Any detail of our behavior can best be understood when it is seen in the context provided by the full range of human behavior. Anthropology seeks to uncover principles of behavior that apply to all human communities. To an anthropologist, diversity itself — seen in body shapes and sizes, customs, clothing, speech, religion, and worldview — provides a frame of reference for understanding any single aspect of life in any given community. To illustrate, imagine having our entire lives in a world of red. Our food, our clothing, our car — even the street we live on — everything around us a different shade of red. And yet ironically, in a scarlet world, isn't it true that we will have no real grasp of the color red itself, nor even the concept of color, without being able to compare red with yellow, blue, green, and all the hues of the rainbow? We [anthropologists] have been the first to insist on a number of things: that the world does not divide into the pious and the superstitious; that there are sculptures in jungles and paintings in deserts; that political order is possible without centralized power and principled justice without codified rules; that the norms of reason were not fixed in Greece, the evolution of morality not consummated in England. Most important, we were the first to insist that we see the lives of others through lenses of our own grinding and that they look back on ours through ones of their own. --Clifford Geertz Evolutionary Perspective As a field, anthropology brings an explicit, evolutionary approach to the study of human behavior. Each of anthropology's four main subfields — sociocultural, biological, archaeology, and linguistic anthropology — acknowledges that Homo has a long evolutionary history that must be studied if one is to know what it means to be a human being. Cultural Anthropology In North America the discipline's largest branch, cultural anthropology, applies the comparative method and evolutionary perspective to human culture. Culture represents the entire database of knowledge, values, and traditional ways of viewing the world, which have been transmitted from one generation ahead to the next — nongenetically, apart from DNA — through words, concepts, and symbols. Cultural anthropologists study humans through a descriptive lens called the ethnographic method, based on participant observation, in tandem with face-to-face interviews, normally conducted in the native tongue. Ethnographers compare what they see and hear themselves with the observations and findings of studies conducted in other societies. Originally, anthropologists pieced together a complete way of life for a culture, viewed as a whole. Today, the more likely focus is on a narrower aspect of cultural life, such as economics, politics, religion or art. Cultural anthropologists seek to understand the internal logic of another society. It helps outsiders make sense of behaviors that, like face painting or scarification, may seem bizarre or senseless. Through the comparative method an anthropologist learns to avoid "ethnocentrism," the tendency to interpret strange customs on the basis of preconceptions derived from one's own cultural background. Moreover, this same process helps us see our own society — the color "red" again — through fresh eyes. We can turn the principle around and see our everyday surroundings in a new light, with the same sense of wonder and discovery anthropologists experience when studying life in a Brazilian rain-forest tribe. Though many picture cultural anthropologists thousands of miles from home residing in thatched huts amid wicker fences, growing numbers now study U.S. groups instead, applying anthropological perspectives to their own culture and society. Linguistic Anthropology One aspect of culture holds a special fascination for most anthropologists: language — hallmark of the human species. The organization of systems of sound into language has enabled Homo sapiens to transcend the limits of individual memory. Speech is the most efficient medium of communication since DNA for transmitting information across generations. It is upon language that culture itself depends — and within language that humanity's knowledge resides. "As you commanded me, I, Spider Woman, have created these First People. They are fully and firmly formed; they have movement. But they cannot talk. That is the proper thing they lack. So I want you to give them speech." So Sotuknang gave them speech, a different language to each color, with respect for each other's difference. He gave them also the wisdom and the power to reproduce and multiply. --Hopi Indian Emergence Myth Linguistic anthropologists, representing one of the discipline's traditional branches, look at the history, evolution, and internal structure of human languages. They study prehistoric links between different societies, and explores the use and meaning of verbal concepts with which humans communicate and reason. Linguistic anthropologists seek to explain the very nature of language itself, including hidden connections among language, brain, and behavior. Language is the hallmark of our species. It is upon language that human culture itself depends. Linguistic anthropologists, of course, are not the only ones who study historical dimensions of culture. Anthropologists recognize that, in seeking to understand today's society, they should not confine attention only to present-day groups. They also need information about what came before. But how can they trace the long-ago prehistory, reaching far back into the millennia, of societies that left no written record? Archaeology Fortunately, the human record is written not only in alphabets and books, but is preserved in other kinds of material remains — in cave paintings, pictographs, discarded stone tools, earthenware vessels, religious figurines, abandoned baskets — which is to say, in tattered shreds and patches of ancient societies. Archaeologists interpret this often fragmentary but fascinating record to reassemble long-ago cultures and forgotten ways of life. Archaeologists, long interested in the classical societies of Greece, Rome, and Egypt, have extended their studies in two directions — backward some 3 million years to the bones and stone tools of our protohuman ancestors, and forward to the reconstruction of lifeways and communities of 19th-century America. Regarding the latter, many archaeologists work in the growing field of cultural resource management, to help federal, state, and local governments preserve our nation's architectural, historical, and cultural heritage. Biological Anthropology But human history begins in a different place further back in time. It starts at least 4 million years ago, when a population of apelike creatures from eastern Africa turned onto a unique evolutionary road. Thus, the anthropologist's comparative perspective must be expanded to include more than prehistoric human societies, for behavior has primate roots as well. To fully understand humankind we must learn more about its place in the natural habitat of living things. Biological (or physical) anthropology looks at Homo sapiens as a genus and species, tracing their biological origins, evolutionary development, and genetic diversity. Biological anthropologists study the biocultural prehistory of Homo to understand human nature and, ultimately, the evolution of the brain and nervous system itself. These, then, are the four main branches that make anthropology whole: cultural, linguistic, archaeology, and biological anthropology. Anthropology asks a most difficult and most important question: What does it mean to be human? While the question may never be fully answered, the study of anthropology — what the noted anthropologist Loren Eiseley has called the "immense journey" — has attracted some of the world's greatest thinkers, whose discoveries forever changed our understanding of ourselves. Know then thyself . . . --Alexander Pope Anthropology as a Career Anthropologists conduct scientific and humanistic studies of the culture and evolution of humans. Each of the four fields of American anthropology has its own skills, theories, and databases of special knowledge. Most anthropologists, therefore, pursue careers in only one of the four subdisciplines. Anthropologists may specialize in two or more geographic areas of the world, such as Oceania, Latin America, and Africa, for reasons of comparison. More than 350 U.S. colleges and universities offer an undergraduate major in anthropology, and many more offer coursework. Because the subject matter of anthropology is so broad, an undergraduate major or concentration can be part of a broad liberal arts background for men and women interested in medicine, government, business, and law. More information on college and university anthropology can be found in the American Anthropological Association's AAA Guide, published yearly. Training A doctorate is recommended for full professional status as an anthropologist, although work in museums, physical anthropology labs, and field archaeology is often possible with a master's degree. There are more nonacademic career opportunities available to Ph.D. anthropologists, currently, than there are jobs in the academy itself. Increasingly, Ph.D. students begin their training with academic as well as nonacademic careers in mind, and seek admission to programs that include applied-anthropology courses. Academic Work Setting Academic settings include departments of anthropology, nonanthropology departments (e.g., linguistics, anatomy, cultural studies, women's studies, fisheries), campus ethnic centers (African American studies, Latino studies), campus area studies (Pacific studies, Mexican studies, Latin American studies), campus research institutes (demography centers, survey research institutes, archaeology centers), and campus museums. Nonacademic Work Setting In recent years, many anthropologists have chosen to utilize their specialized training in a variety of nonacademic careers. Cultural and linguistic anthropologists work in federal, state and local government, international agencies, healthcare centers, nonprofit associations, research institutes and marketing firms as research directors, science analysts and program officers. Biological anthropologists work in biomedical research, human engineering, private genetics laboratories, and pharmaceutical firms. Archaeologists work off campus in environmental projects, human-impact assessment, and resource management. At present there is no discernible limit for Ph.D. anthropologists targeting the nonacademic realm for employment. The global economy's focus on internationalism, information and research and anthropology's world of interests mesh. Today, half of new doctorates find professional jobs off campus. Additional information on careers in anthropology is available from AAA. For More Information The American Anthropological Association (AAA), founded in 1902, is the world's largest organization of men and women interested in anthropology. Its purposes are to encourage research, promote the public understanding of anthropology, and foster the use of anthropological information in addressing human problems. Anyone with a professional or scholarly interest in anthropology is invited to join. For further details, please contact AAA. Authored by David Givens Appendix F: Reflection and Consideration Outcome Indicator of Mastery Discuss and evaluate the ideas, and theories of prominent social scientists Demonstrate an understanding of the different disciplines involved in the study of individuals and groups in society (sociology, psychology and anthropology) Demonstrate an understanding and appreciation of concepts and methods used in the social sciences. Level of Mastery 1-5 /15 1. (Reflection) Which field seems to hold the most interest sociology or anthropology? 2. (Consideration) How could you say that cultural anthropology was related to sociology? 3. (Reflection) You may need to refer back to your notes. Which key people and theories are represented in this film? Please describe the theories in your own words and make sure you include the names of the theorists. 4. (Consideration) A law in the social sciences holds that predictions of human behaviour cannot and should never be derived from observing animal interaction. What do you think? 5. (Reflection) You are remaking this film. Pick two characters from the list of theorists and create one as the protagonist and the other as the antagonist. How would you set up their conflict? What would their conflict be? Who would win? What is the plot? Appendix F: Outcomes of Unit 1 Upon completion of this unit, students should be able to: 1Discuss and evaluate the ideas, and theories of prominent social scientists 2Demonstrate an understanding of the different disciplines involved in the study of individuals and groups in society (sociology, psychology and anthropology) 3Demonstrate an understanding and appreciation of concepts and methods used in the social sciences. 4 Apply social science methods to specific situations. 5 Work co-operatively to apply these concepts and methods. 6 Explore sources of bias, understand how to detect bias, explore personal bias and reflect on ways to reduce bias. 7 Examine evidence using sociological methods of inquiry Evaluation Task: Address your understanding of the outcomes in paragraph form. To address the outcomes properly this should be fairly lengthy at take at least 3-5 pages double spaced. Typed evaluations are preferable, therefore you will be given time in school to complete this evaluation. Remember that if you do not have access to a computer at home the Sackville Public Library offers free computer access. We will complete the chart labeled Outcome Understanding in class. You should use this chart to complete the evaluation as well as any notes and received assessments. Notes: Outcome Understanding Outcome Number 1 What we have worked on to complete this outcome 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Due Date Assigned: Evidence of Mastery in the Written evaluation Comments