View/Open - Sacramento

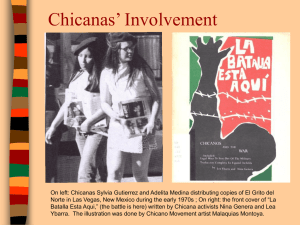

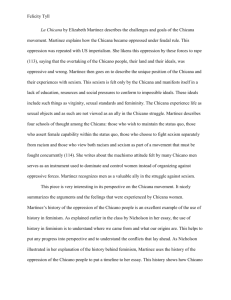

advertisement