here - Shelley F. Diamond, Ph.D.

advertisement

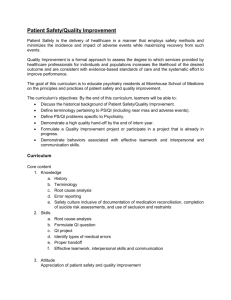

Mental Health Services for Elderly in Their Homes by Shelley F. Diamond, Ph.D. Summary This report describes a two-year mental health program for 200 culturally diverse seniors living in private apartments in a residential community. Successes and limitations of the program are outlined, including specific factors that contributed to outcomes. Introduction Rates of psychopathology in seniors over age 65 have been estimated at 13-20%, and many conditions are underdiagnosed, especially depression (Druss, Rohrbaugh, & Rosenheck, 1999; Jeste et al., 1999; Unutzer et al., 1997). Mental health services are typically underutilized and access is poor (Bartels, Horn, Sharkey, and Levine, 1997; Mental Health Report of the Surgeon General, 1999). Fewer than 3% of older adults report seeing a mental health professional, lower than any other adult age group (Olfson & Pincus, 1996). Barriers to treatment include physical mobility issues, financial constraints, and lack of awareness of the benefits of psychotherapy (Yang & Jackson, 1998). Innovative programs do outreach to the elderly in the places where they live (Yang & Jackson, 1998). Methods Staff at a residential community for seniors perceived the need for mental health services and contacted the Institute on Aging. A pilot mental health program was set-up under the umbrella of an established Well Elder Program (in which a nurse is available for minor medical check-ups and consultations). A psychologist was assigned to come to the apartment building for four hours a week. She conducted psychoeducation workshops for residents and staff, did individual psychotherapy sessions with residents in their own apartments, and coordinated care with other professionals. The psychologist received special training on issues related to doing psychotherapy in a person's home, where traditional boundaries of the therapy office do not exist. Due to concerns that seniors would have fears about a psychologist suddenly becoming part of the community, a plan for consistent but low-key exposure was put into effect. The psychologist was introduced to the residents at a group meeting by the building manager, social worker, and Well Elder nurse. For the first two months, the psychologist attended holiday events, birthday parties, and weekly gatherings over morning coffee. She introduced herself to as many people as possible, socializing informally, handing out contact information, explaining that she would be available every week, and answering questions about services. A casual matter-of-fact style was used, emphasizing the importance of health in both body and mind for successful aging, and de-emphasizing mental illness. The psychologist then presented a number of psychoeducational lectures on relevant topics, including Stress Management, Relaxation Techniques, Chronic Pain and Illness, Memory Loss, and Life Changes and Transitions. At the end of each presentation, she answered questions and explained that residents could schedule private follow-up sessions in their apartments to discuss personal issues. At the end of each presentation, at least one or more residents scheduled a private appointment. At the same time, staff began to refer people for services and follow-up intake interviews were conducted in residents' apartments. In between private sessions, time was spent in the common areas of the building, making informal contact with whoever was there, exchanging names, expressing concern about residents' well-being, and offering informal consultations. Gradually, there were more residents interested in services than could be handled by one person. A social work intern began to do the intake interviews and pre-doctoral interns began seeing patients. The psychologist also attended building staff meetings to help staff deal with the difficult behavior of some residents. This role as consultant was critical to help staff feel supported, and 2 to increase their understanding of residents' behavior. Careful thought was given to issues of confidentiality and privacy, sharing information with building staff only when necessary. A nonprofit foundation gave minimal monthly financial support. Insurance was accepted and a sliding scale was available. As more and more people without financial resources requested services, the foundation began to subsidize psychotherapy fees. At any one time, approximately half the residents seen in weekly psychotherapy had subsidized fees. This program was economically feasible within the context of a mental health training facility that focused on a geriatric population. Given the low level of Medicare reimbursement, individual psychologists would likely need grant money to sustain their practice. Results Over time, there was a growing acceptance of and receptiveness to mental health services. By the end of two years, the traditional stigma associated with mental health was greatly reduced. Word of mouth spread that the mental health clinicians were people with whom they could safely talk when they needed help. Residents and staff openly welcomed the psychologist upon her arrival at the building each week, many acknowledged her in the halls and elevators, and felt comfortable asking her questions in public or in a private room available to all residents. By the end of the two years, there was enough need for several clinicians to come to the building to do individual psychotherapy sessions. Psychological concepts needed to be demystified with nonclinical language. Cultural differences needed to be accepted and flexible attitudes maintained. Creativity was essential in contacting residents with hearing impairments who could not use the telephone, did not hear knocks at the door, and/or could not hear conversational speech. Examples of situations in which services were needed included: a psychotic episode in which a resident had to be hospitalized, neglect that required reports to Adult Protective Services, dementia that involved a capacity declaration and assignment of conservators, depression and suicidal ideation 3 due to chronic pain, hoarding that created a fire hazard and caused the resident to fall, and post-traumatic stress. Less severe issues included concerns about memory loss, bereavement or grief over losses and changes in their lives, fears of gossip among neighbors, social isolation, family conflicts, depression and/or anxiety due to chronic medical conditions, disabilities, and/or lifestyle restrictions, medication issues, and a wide range of other stresses and concerns typical for an elderly population. The successful evolution of the mental health program can be partly attributed to the slow and gradual start-up of services in which residents were gradually exposed to the concept of mental health needs in psychoeducation classes open freely to all, and individual psychotherapy for a fee offered as additional option. Residents were probably also influenced by building staff, who all strongly supported the integration of mental health services and encouraged the psychologist's participation in all aspects of the community from the beginning. Other critical factors in the program's growth included maintaining a consistent, visible, informal, reliable, friendly presence in the building on a weekly basis. Participation in social events demonstrated a willingness to become a part of the community. Psychoeducation presentations gave residents an opportunity to get questions answered before making a commitment to psychotherapy. Since there were a large number of non-English-speaking residents, interventions would have been improved by having a more linguistically- and culturally-diverse staff of clinicians. A couple of psychoeducational lectures were translated (into Mandarin and Russian) but there were not enough trained bilingual clinicians to see residents in individual psychotherapy sessions. Other limitations included problems arranging sessions with residents who were suspicious of all strangers and/or had memory loss which interfered with their ability to remember appointments or follow conversations. Conclusions The two year pilot program demonstrated the need for mental health services in independent living apartment buildings 4 for seniors, and also showed the potential for success in delivering effective care and treatment. The program seemed to be helpful to most residents in acknowledging and reinforcing their strengths and abilities, and facilitating medical and/or psychosocial services when needed. Training to conduct psychotherapy in home visits was critical. References Bartels, S.J., Horn, S., Sharkey, P., Levine, K. (1997). Treatment of depression in older primary care patients in health maintenance organizations. International Journal of Psychiatry and Medicine, 27: 215-231. Druss B.G., Rohrbaugh, R.M., Rosenheck, R.A. (1999). Depressive symptoms and health costs in older medical patients. Am. J. of Psychiatry, 156: 477-479. Jeste, D.V., Alexopoulos, G.S., Bartels, S.J., Cummings, J.L., Gallo, J.J., Gottlieb, G.L., Halpain, M.C., Palmer, B.W., Patterson, T.L., Reynolds, C.F., and Lebowitz, B.D. (1999). Consensus statement on the upcoming crisis in geriatric mental health. Archive of General Psychiatry, 56: 848-853. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. (1999). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD. Olfson, M., and Pincus, H.A. (1996). Outpatient mental health care in nonhospital settings: Distributions of patients across provider groups. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153: 13531356. Unutzer, J., Patrick, D.L., Simon, G., Grembowski, D., Walker, E., Rutter, C., Katon, W. (1997). Depressive symptoms and the costs of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. JAMA, 277: 1618-1623. Yang, J.A., and Jackson, C.L. (1998). Overcoming obstacles in providing mental health treatment to older adults: Getting in the door. Psychotherapy, 35: 498-505 5