The Coriolis “Force” Part 2:

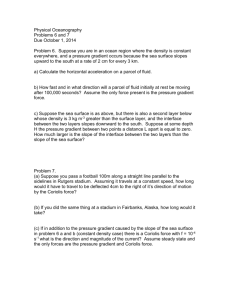

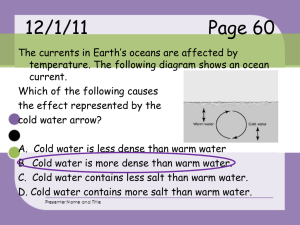

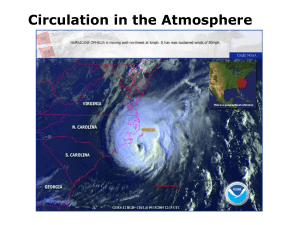

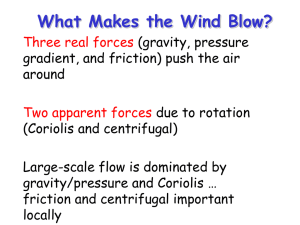

advertisement

The Coriolis “Force” Reading Knauss pages 87-95. Some useful web sites http://www.physics.ohio-state.edu/~dvandom/Edu/newcor.html http://satftp.soest.hawaii.edu/ocn620/coriolis/ Something funny but not useful and propagates a myth about the Coriolis force. The Simpson’s—‘Bart vs Australia” What is the speed of a rotating object? Suppose a particle was on a disk that rotated once each second. The speed of the object would be v=2r, where r is the radius,. In this example the rotation rate is 2 radians per second. Often we write the rotation rate as, which can be called the angular velocity and has units of frequency (2*pi/time). How long does it take for the earth to rotate once? You’d probably guess 24 hours. But in fact it rotates once every 23 hours 56 minutes and 4 seconds. So the earth actually spins more that ones in 24 hours but once and 1/(365.25)th of a rotation. This is because as the earth spins it also moves around the sun and thus requires a little more rotation to have the same orientation with the sun as it did 24 hours earlier. Since on earth the Sun is our main time-piece we call 24 hours one day—the amount of time from noon to noon. But if we’re interested in the rotation of the sun in fixed space —the inertial reference frame—we use the Sidereal Day. This is why the stars in the sky sift slightly each night. In fact the stars along the earth’s ecliptic- where the 12 Zodiacs lie- appear 3 minutes and 56 seconds earlier each day due to the difference between the sidereal day and our solar day. Now suppose there is a frictionless particle on the earth. This particle, if it is to stay at the same location on this rotating frame, must accelerate in such a way that it moves with the underlying earth. Before I get into how this happens –lets look at what the accelerations are like and how they vary with latitude. A decent derivation of the force appears on 89 of Knauss and a more complete one follows on page 90 in box 5.3—but that one requires vector calculus so in class I’ll go over the more simpler one on page 89. The vertical component of this accelerations impacts gravity. How big is the centrifugal acceleration? On the equator the earth spins at 1000 miles/hour or 464 m/s. The earths radius is ~6380 km, so the centrifugal acceleration is (v2/R) is =.03 m/s2. This can be figured out a different way. The angular velocity of a spinning body can be written as R , where is the rotation rate is radians per second (for example if = 2 the body would rotate once time around – or 2 radians each second). The earth rotates 2 radians every 23 hours 56 minutes and 4 seconds so 7.3 x 10-5 s-1. So the centrifugal acceleration v2/R = 2 R . In addition to this gravity is reduced further at the equator due to the equatorial bulge (the radius of the earth at the equator is 22 km larger than at the pole). Together these contribute to a gravitational difference of 0.5% between the pole, where it is 9.83 m/s2 and the equator where it is 9.78 m/s2. If Santa weighs 250 lbs at home (at the pole) what would he weigh on the equator? Would gravity be different on a ship traveling 10 m/s eastward on the equator from a ship heading 10m/s westward on the equator? The earth’s gravitational field is further complicated by the earth’s structure— which is not flat nor smooth. The example in figure 5.8 (page 96) shows how increased gravity over a ridge results in a rise in the sea-surface, while reduced gravity over a trench results in reduction of sea-surface. The variations in gravity occur because the gravitational vector is pointing to local regions of enhanced mass—and since the earth’s crust is heavier than the ocean’s waters it tends to point away from the trenches and towards the ridges. This can result in sea level rising 10’s of meters with slopes on the order of 1 meter per kilometer. Yet this does not drive any motion. Why? For particle purposes, at least as far as ocean circulation is concerned, we can forget about the earth’s gravitational anomalies, and set g=9.81 m/s2. While we can invoke slight variations in gravity to deal with the vertical acceleration how do we get the horizontal accelerations? Lets use the pole as an example where the rotation can be thought of as that of a turntable. If we started rotating a frictionless fluid that was at rest on a turntable it would never turn but rather remain motionless relative to fixed space while the turntable spun underneath it. Relative to the turntable the fluid would complete a circle once each rotation in a sense opposite to that of the rotation of the turntable. However, no matter how hard we try, we have yet to find a frictionless material outside of a physics book, so the fluid will eventually begin to spin and at some time later will be in what is called solid body rotation and will have no motion relative to the turntable. In this state the fluid is now constantly accelerating inwards. This is achieved by a pressure gradient being set up in the disk with higher elevations on the sides and a low in the middle. Thus the fluid accelerates down hill at exactly the same rate that the table turns. A similar thing happens in the ocean and atmosphere whereby a pressure gradient has been set up in such a way that allows the fluid to accelerate at the same rate that the earth rotates. This inward acceleration is called centrifugal acceleration and is equal to v2/R where v is the speed that the tank is moving around and R is the radius of the tank. This can also be written as 2Rsin( where is the rate of rotation and is the latitude.. As far as I nobody has proposed a clear and convincing physical interpretation for the Coriolis force! To quote Henry Stommel from his book with Dennis Moore “The Coriolis force” “All professional meteorologists and oceanographers encounter this mathematical demonstration at an early stage in their education. Clutching the teacher’s hand , they are carefully guided across a narrow gangplnak over the yawing gap between the resting frame and the uniformly rotating frame. Fearful of looking down into the cold black water between the dock and the ship, many are glad, once safely aboard, to accept the idea of a Coriolis force, more or less with a blind faith, confident that it has been derived rigorously. And some prefer never to look over the side again. So, when they are asked for an explanation by a landlubber standing on the dock, who has never been carefully guided across the perilous plank, they find themselves singularly unable to explain the curious force. Incomplete explanations abound in popular books and magazines.” SO despite the relatively complex math required to describe the effect of moving about on a rotating earth and non-intuitive result—mathematically this result can be incorporated into the momentum equation. u 1 fv t v 1 fu t forces x forces y (1) (2) Think about the size of the term fv. At 45 degrees latitude f is 10-4 so a particle moving to the north at 1 m/s will accelerate to the east at 10-4 m/s2—indeed a very small number. After 100 seconds it will have obtained a speed of l mm/s to the east—corresponding to a change in direction of about 1/20th of a degree. So if you’re walking northward at 1 m/s the Coriolis force along would have you walking 1/20th of a degree to the east of north after one minute. HOwever you never get to feel this because other forces – such as friction and the forces that you put into walking are probably 1000’s of time larger than this. If you forget which equation has the negative sign on the right hand remember that in the northern hemisphere the flow turns to the right. So northward velocity (v positive) accelerates the flow to the east (u positive). In contrast a eastward velocity (u positive) accelerates the flow to the south (v negative). In the northern hemisphere f is postive—so equations 1 and 2 describe circular motion in a clockwise direction. Draw this out and see that the flow is always turning to the right and thus flows clockwise. This motion is also called cum-sole meaning with motion moves in the same direction that the sun moves across the sky or anti-cyclonic for it is in the opposite direction of the flow around a cyclone. The magnitude of Coriolis parameter (which has the units of frequency) changes with latitude. The Coriolis frequency equals sin(), where is the latitude in degrees and T where T is the number of seconds in a Sidereal Day (86164 s). On the north pole f=1.45 x 10 –4, and the inertial period—the time for a particle governed by the momentum balance described by 1 & 2 to complete one circle, is 11.96 hours. At our latitude f= 9.37 x 10 –5 and the inertial period is 18.6 hours. In the tropics at 18 degrees north f=4.5 37 x 10 –5 and the inertial period is 36 hours. At the equator f=0 and the inertial period is infinity. At 40 degrees south f=- 9.37 x 10 –5 and the Coriolis effect accelerates a moving particle to the left. If you’re willing to accept at face value these arguments then all you need to know is that f=2sin (lat) and that it enters our momentum equation relative to a rotating earth as shown above in equations 1 and 2. Two simple cases are presented—that will be discussed in more detail later in the semester. The first what oceanographers call inertial motion because it’s motion that occurs on the earth solely through it’s own inertia (note that Newton’s famous law – a particle remains in motion at a constant speed and direction unless it is acted on by another force – is for a fixed coordinate frame and not a rotating frame). Inertial motion is shown in examples 4 and 5 of the animations of the rotating disk. Note that if there are no forces (other than this apparent force we call the Coriolis force) and we multiply equation 1 by u and equation 2 by v (without the sum of the forces term) and add them up we obtain (u 2 v 2 ) 0 t Or in other words despite the changing motion the kinetic energy remains the same but the direction of the motion changes. Later we’ll look more into this A second example is a Hurricane. Here the Coriolis force balances the pressure gradient and the winds flow along isobars rather than cross them. This type of momentum balance can be written as: 1 P fv x 1 P fu y and is called geostrophic flow. In large scale weather systems (100’s1000’s of km) most of the momentum balance is between the Coriolis force and the pressure gradient (figure 3). In this case winds flow along isobars rather than across them. It is why winds flow clockwise around a high (in the northern hemisphere) and counter-clockwise around a low. When is the Coriolis force important? Figure 3. Atmospheric pressure in milibars (mb) at a height of 500 mb showing higher pressure to the south. Wind speed is indicated by number of sticks on the wind vector. Note the strongest winds occur where the pressure gradient is largest off the NW coast. One way to determine if the Coriolis force is important is to compare it to other terms in the momentum equation. A particularly relevant force to compare it to is the centrifugal acceleration – because it sort of like the Coriolis acceleration. The centrifugal force is equal to v2/R where v is velocity and R is the radius of curvature. So if both forces are at work they can be written as: v2/R + fv=v(v/R +f) so the importance of the Coriolis force can be determined by comparing f to V/R. First I will deviate from a this with a Question: Why doesn’t this term v2/R appear in the momentum equations that we’ve written before? Answer: Because they were written in Cartesian coordinates. If we were to transform the advective terms in the momentum equation to polar coordinates the v2/R term would appear. So the advective terms in the momentum equation that we’ve been writing in class and the centrifugal acceleration are the same. The both involve a changing velocity vector (Figure 1) and both are nonlinear—they involve velocity squared. v2 R u u v x y v v u v x y u R Figure 1. Schematic of eddy to demonstrate that advective term in the momentum equation in Cartesian coordinates is similar to centrifugal acceleration. So does the toilet flush the way it does because of the Coriolis effect? Let’s assume that the flow in the toilet is 1 m/s. The Coriolis effect would accelerate the flow at a rate of 1 m/s * 9.37 x 10 –5 m/s2. Thus in the 10 seconds it takes to flush the toilet the fluid moving down the slope of the bowl would acquire a flow to the right at a speed of * 9.37 x 10 –4 m/s2 or less than 1 mm/s. Compare this to the centrifugal accelerations in the toilet (v2/R) (assume R = 20 cm) and we find that the centrifugal accelerations are 5 m/s2—or 40,000 times larger then the Coriols effect. Note that you can compare these two terms v2 R v fv fR (3) Where R is the radius of the toilet. Several things to note about equation 3. First for our toilet bowl example it equals over 50,000 -- indicating that effects of the earth’s rotation are over 50,000 times smaller than those associated with centrifugal acceleration. Secondly note that 3 is dimensionless -- so we’ve come up with another non-dimensional number. This one is known as the Rossby Numberafter Carl-Gustaf Rossby, (who appeared on the cover of TIME magazine in 1956) More generally this can be written as v R (4) fL Where L is a characteristic length scale. It is a ratio of the fluid’s inertia to effects of the earth’s rotation. When the Rossby number is near 1 or less effects of rotation are important. (like all non-dimensional numbers it’s value should be viewed as an order of magnitude estimate). Consider a weather system with a length scale of 500 km, winds 20 miles per hour (~ 10 meters/sec) at 40 degrees north. Here the Rossby number is ~ 0.1 and the effects of the earth’s rotation are clearly important. For a Hurricane v=100 miles/hour =44 m/ s The length scale of a hurricane is ~ 200 km. At a latitude of 30 N the Rossby number is about 3—indicating that effects rotation are important but that effects of the winds inertia also play an important role in the dynamics. In the ocean if currents are 50 cm/s and for f=10-4 any feature with a length scale of less than 20 km will have a Rossby number less than 1. Note that in the ocean because velocities are smaller than in the atmosphere that in the ocean the earth’s rotation effects smaller scale features than in the atmosphere. Subsequently the eddying motion in the ocean is of a much smaller scale than that in the atmosphere. This is a challenge to ocean modelers because to capture all the eddying motion in the ocean requires a much finer resolution than atmospheric modelers require. In both the atmosphere and the ocean the first order balance is what we call “Geostrophic” in which the pressure gradient is balanced by the Corolis acceleration. In this balance the flow is steady—and thus if you know the pressure gradient you would know the velocity. This has been useful to Oceanographers who can measure the density field in the ocean and calculate the pressure gradient and thus estimate the Geostrophic velocity of the ocean. However, this requires an assumption that the pressure gradient goes to zero at some depth. This can happen if isopycnals tilt in the opposite direction of the barotropic pressure gradient and produce a lower layer with no pressure gradient and thus no geostrophic velocities occurs this level. As such we call this the level the level of no motion. Since we have velocity above the level—and no velocity below—we have vertical shear. Note that this requires a tilting of the isopycnals and this corresponds to a horizontal density gradient.