The Cosmological Argument

advertisement

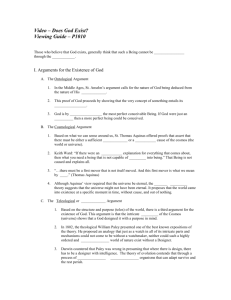

The Cosmological Argument History This argument - along with the previously discussed teleological argument - was first introduced by the Greek philosopher Plato (428-347 BC) in book X of the Laws. It was later taken up by St Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) who included it in his Five Ways (part of his Summa Theologica) where it represents the First Way of realising the existence of God. Summary The cosmological argument is based ultimately on the existence of the cosmos (hence the name) and its main gist is that for something to move it must first be caused to move by something else. So, if we look at the world, Plato argues, there must be a first cause of all this motion - that is, something that set it all going. However, for this cause to be the ultimate one it must itself be unmoved by anything else (an unmoved or prime mover). This principle Plato called 'soul' or 'life'. Plato Plato's argument is based on the idea that a thing cannot be self-moving. By this he means that if, for instance, we see a ball flying through the air, we must assume that something caused that ball to move. If we then say that the ball moved because it was hit by a bat, we can then ask what caused the bat to move - and so on infinitely. From this Plato concludes that there must be some first cause of motion which is not itself the result of some other cause. For Plato, this was "Soul" or "Life", which gave motion to the whole world. Discussion Is Plato right in trying to argue that motion must have started from an ‘unmoved mover’? What problems might there be in this? Are there any examples you might use to contradict this view? Aquinas St. Thomas Aquinas' argument is similar to Plato's except that Aquinas concludes that the source of all motion must be God. Aquinas then goes on to give four other arguments which he claims point to the existence of God - these are called the Five Ways. The first, as already described, uses the idea of motion; the others are as follows: Second way: Everything that exists must have a cause. There must have been a first cause that was not caused by anything else otherwise this process would go on for eternity. This first cause must be God. 6 Third Way: Everything that exists at one time did not and may not at some time in the future. However, at one time none of these things existed - there was nothing - but because "nothing can come from nothing" there must have been something whose existence was necessary (a being which had to exist). This being must be God. Fourth Way: Things in the world have different qualities and degrees of perfection and goodness. There must be an ultimate in goodness and perfection. Therefore, God must exist as the source of these qualities. Fifth Way: Everything in the world has some 'end' or 'purpose'. This purpose must come from an intelligent being and not chance. Therefore, God provides everything that exists with purpose. Exericses 1) Look at Aquinas’ five arguments and try to summarise the essential point being made (this will make it easier for you to remember each argument). 2) Now, go through each argument in turn. Are there any problems that you can think of? 3) Which is the strongest of Aquinas’ arguments? Why? 4) Like the teleological argument, the cosmological argument argues from the existence of certain qualities in the world to the existence of God. Take the following 3 things and think about what we can infer about the qualities of a cause from its effect. What problems might there be in this argument for the religious believer? a) A mountain b) A watch c) A human being d) A painting e) A rabbit 7 The Ontological Argument History The argument was first put forward by the Christian theologian St Anselm (1033-1109) in his work the Proslogion, but was later picked up by the French philosopher Rene Descartes (15961650) who modified it slightly to concentrate on the idea of God's perfection necessarily involving existence. Summary The word "ontology" is a Greek word relating to the concept of being. The ontological argument itself therefore argues the existence of God by saying that His being by nature includes the concept of necessary existence. St. Anselm Anselm's view can be summarised as follows: 1. Nothing greater than God can be conceived. 2. The idea of God exists in our mind. 3. If God only existed in our minds He would not be as great as one who actually existed. 4. Therefore, the idea of God - as a conception which cannot be bettered - must correspond to one in reality (i.e. He actually exists). Discussion 1) If the idea that a type of thing "than which no greater could be conceived" must necessarily exist, might this not apply to the most perfect potato, or the best golfer? Must they necessarily exist too? 2) Aquinas' response to the above argues that necessary existence cannot apply to ordinary things (such as potatoes and golfers) because material things can go in and out of existence (someone might make chips out of the perfect potato) - this, however, does not apply to God. Is this a good argument? Descartes Descartes' modification of the argument concentrates on the idea of God as the most perfect being. This argument states that a God who does not exist would be less perfect than one who did. From this point of view, existence is considered as one of God's perfect qualities. 8 Discussion Descartes' modification of the cosmological argument involves considering existence as a perfection - but can existence be compared to other perfect qualities (such as "goodness", "justice", etc.)? 9 The Argument from Morality History Cardinal Newman in his Grammar of Assent (1870) argued that the existence of a conscience as a guiding part of our mind pointed to a source of morality outside of us. From Newman's viewpoint, because our conscience causes us to feel shame when we do wrong and to fear punishment, the necessary object of such fear, and the source of the moral code itself, is God. A more complicated version of this argument was put forward by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) who argued that the moral law existed as an objective reality. Although not intended as a proof for the existence of God, Kant argued that human beings felt a duty - what he termed a categorical imperative - to act in accordance with this moral code. Others have argued from what is termed the "just deserts" standpoint, claiming that the idea of God is necessary in order to make sense of why people don't just simply act in whatever way they see fit. John Hick, in his book Arguments for the existence of God, argues that such acts as sacrificing one's life to save another do not make sense unless we suppose that there is some reward - either now, or after death in some form of afterlife. Summary The moral argument states that the existence of God must be supposed in order to account for the fact that human beings have developed moral codes. From this point of view, the very idea that there is such a thing as a conscience which influences us to behave unselfishly argues for the existence of something which created it. The moral argument therefore argues that this source is God himself. Exercise Newman's argument supposes that there is some outside force that is responsible for the existence of morality and conscience. Even if this were so, does this have to be God? List what you think might be the other possible sources for conscience. Possible Sources 10 Discussion 1) What insight might different societies give us into this argument? 2) How do the existence of different religious belief systems affect this argument? Are there any possible defences against these criticisms? 11 The Argument from Miracles History Miracles have always been seen as evidence that some supernatural power is present. However, it is only in more recent times that their existence - or not - has come to be seen as proof of divine existence (before this, it was more a sign that some individual was divinely inspired or possessed godly powers). The most telling attack on the possibility of miracles comes from the Scottish philosopher David Hume who attacked the very idea that (a) they could exist, and (b) that we they could be used to prove God's existence. A more detailed account of Hume's views can be found in the section devoted to miracles. Exercises 1) List what you see as the problems associated with authenticating a traditional miracle. Problems Points for Discussion 1) Nineteenth century medicine and psychoanalysis first showed that people may suffer from what are termed "hysterical symptoms". Because of psychological stress, they found that a patient might develop such things as blindness, paralysis and dementia. However, these symptoms could "miraculously" disappear when the right psychological trigger was found. Will all "miracles" one day be explained away by science? 2) Is there any reason that even if an event is inexplicable we should ascribe its origin to divine intervention? 3) Even if a miracle could be authenticated, could it tell us anything about the nature of God? 12 Exercise What might a sceptic say about the following "miracles": a) A man who has been pronounced clinically dead revives after two days. b) A woman who falls asleep at the wheel of a car wakes up to find that she has crashed harmlessly into a haystack. c) A soldier whose parachute does not open survives a fall of thousands of feet with only a few scratches. d) Rushing to catch a plane, a man is delayed by an encounter with a drunk. He misses the plane which later crashes leaving no survivors. 13 The Argument from Religious Experience History The problem of verifying religious experience is an old one. St. Theresa of Avilea was accused of being in league with evil spirits, but argued that her vision was of divine origin. Jesus himself was accused of the same thing because he was able to cast out demons. It seems that the notion of origin - where these experiences come from - is all important when we consider whether such an experience is proof or not of God's existence. Descartes highlighted many of the problems when he showed just how uncertain most of our everyday perceptions were - let alone those of supposed divine origin. Thomas Hobbes (15881679) similarly asked how it was possible to know whether God spoke to you in a dream, or whether you simply dreamed that God spoke to you. A further issue was raised by A. J. Ayer (1910-89) when he pointed out that mystical experiences are usually only descriptive of the inner experience of the person who has them - not of the objective existence of the being who is said to produce them (i.e. God). From a sympathetic viewpoint, William James (1842-1910) argued that mystical experiences cannot simply be discounted - no more than everyday ones can be. For instance, if we say that St. Paul was an epileptic, and try and account for his visions in that way, we also have to explain how certain acceptable everyday states of mind may also resemble types of mental illness - think of being in love! Summary The most direct argument for the existence of God is that which claims actual experience of God. Such an argument is the oldest form of religious justification but is also arguably the most controversial. Whereas the other arguments rely on some form of logical persuasion, the religious experience argument relies totally on the authenticity of such an experience. From the point of view of the potential convert there is no need that the experience be a direct personal one. Trust or faith in the genuine experience of another may also act as proof of a divine being. However, criticisms of the argument are primarily concerned with the possibility of such an experience, and secondarily with how it might be possible to authenticate another's testimony. We will return to the problems associated with religious experience later on in more depth. Points for Discussion 1. One of the criticisms of this argument is that the notion of God is an impossible one anyway. Is this conclusive? 2. We have all had experience of being deceived by things - through simple mistake, hallucination through illness, etc. Could religious experiences therefore be an example of this? 14 3. Both psychology and sociology provide persuasive reasons for rejecting the authenticity of religious experiences. Is it therefore better to accept alternative explanations because they are more probable? 4. It is possible for two people to view the same experience in very different ways and yet for both of those experiences to be valid (think of seeing a film, or listening to music). Could religious experience be explained as simply a matter of seeing the wonder of the world? 5. Would the above view of religious experience avoid the problems of authenticity? What would then differentiate it from drug-related experiences, or euphoria arising from tiredness or illness? 15