Module 2 GEPRISP model

Module 2

GEPRISP

Module 2

GEPRISP

Whakataukī: Me mahi tahi tātou mo te oranga o te katoa.

Literal: We must all work as one for the well being of all.

Overview

This module outlines the core elements of Te Kotahitanga as they are encapsulated in the acronym, GEPRISP. Each element is defined and examined in detail. The links between

GEPRISP and practice are outlined in terms of classroom practice and the implementation of the professional development programme. The synergistic nature of GEPRISP is examined and specific examples are provided of how the GEPRISP model guides all levels of Te

Kotahitanga.

Section Contents

1 Background

2 Making sense of Discourses and Discursive Positioning The

Link to Te Kotahitanga

Page

2

3

3

4

5

6

7

8

Understanding the elements of GEPRISP

PSIRPEG: Gathering evidence of the effects of implementation

GEPRISP/PSIRPEG and the professional development

The elements of GEPRISP

The synergy of the elements of GEPRISP

Reviewing GEPRISP: Activity template

References

4

7

11

12

24

25

28

Section 1: Background

The professional development model in Te Kotahitanga applies each aspect of GEPRISP

(Goal, Experiences of Māori students, teacher’s discursive Positioning, Relationships,

Interactions, Strategies and Planning) across both the implementation of the professional development and the evaluation of its implementation. In this model The Effective Teaching

Profile is operationalised at multiple levels: between Māori students and teachers in classrooms, between teachers and facilitators, and between the Research and Development team and facilitators.

Module 2

2

Section 2: Making Sense of Discourses and Discursive Positioning

Parker (1992) defines a discourse as “a system of statements which constructs an object”

(p.5). Burr develops this idea further by asserting that a discourse refers to “a set of meanings, metaphors, representations, images, stories, statements and so on that in some way together produce a particular version of events” (1995, p.48).

In Te Kotahitanga the concept of discourse is understood as the sets of ideas, often influenced by historical events, that influence one’s practices and actions, how one relates and interacts with others, and, as a result, how one understands and explains those experiences (Bishop, Berryman, Powell & Teddy, 2007; Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai &

Richardson, 2003). Discourses are recognised as having a major influence on the images and experiences that teachers and Māori students have of each other, and therefore on their relationships and interactions.

Burr (1995) makes the point that, “numerous discourses surround any object and each strives to represent or construct it in a different way… claims to say what the object really is, claims to be the truth”. However claims as to what is the reality, what is the truth, “lie at the heart of discussions of identity, power and change” (p.49). Burr suggests that the meaning behind what we say “rather depends upon the discursive context, the general conceptual framework in which our words are embedded” (p.50). One’s actions and behaviours, how one relates to, defines and interacts with others, are determined by discursive positioning, that is the discourse within which one is metaphorically positioned. Discursive positioning therefore can determine how we understand and define other people with whom we relate

(Bishop, et al., 2003; Bishop, et al., 2007; Shields, Bishop, & Mazawi, 2005).

The Ministry of Education’s strategic direction, aimed at improving education for Māori, is informed by outcomes and targets set by the government’s Education Priorities, by the

Ministry’s Statement of Intent, by strategic work emerging from Hui Taumata Mātauranga and by partnerships forged between iwi Māori and the Ministry of Education (Ministry of

Education, 2005a). It has been argued that Māori aspirations could be better met within bicultural discourses such as these (Durie, 1998). However, from previous experience, these initiatives are unlikely to make a difference unless they also attempt to address the dominant discursive positioning, inherent in many colonised societies that pathologises the indigenous condition (Shields, et al., 2005; Walker, 1990) including that of the indigenous

Māori population in New Zealand (Bishop, et al., 2003; Bishop, et al., 2007; Smith, 1999).

The Link to Te Kotahitanga

It is a fundamental understanding of the Te Kotahitanga project that until teachers consider how the dominant culture maintains control over the various aspects of education, and the part they themselves might play in perpetuating this pattern of domination, albeit unwittingly, they will not understand how dominance manifests itself in the lives of Māori students (and their communities) and how they (as teachers) and the way they relate to and interact with Māori students may well be affecting learning in their classroom. Therefore, the professional development devised by the researchers includes a means whereby teachers’ thinking can be challenged, albeit in a supported, private way.

Module 2

3

Cognitive and affective dissonance, in effect, cultural dissonance, which Timperley, Phillips and Wiseman (2003) identify as being necessary for successful professional development, can lead teachers to a better understanding of the power imbalances of which they are a part, in particular those power imbalances which perpetuate cultural deficit theorising and support the retention of traditional transmission classroom practices. Changing teachers’ explanations and practices (discursive repositioning) about what impacts on Māori students’ learning, involves non-confrontational ways for teachers to challenge their own deficit theorising about Māori students (and their communities) through real and vicarious means.

Section 3: Understanding the Elements of GEPRISP

GEPRISP, as the model for implementation of the professional development, begins by acknowledging and highlighting the need for the specific GOAL of improving Māori student participation and achievement. Māori students’ EXPERIENCES of education and those of their significant others are then used in a problem-solving exercise at the Hui Whakarewa

(Module 6A) which allows for a critical examination of teachers’ discursive POSITIONING and the implications for classroom relations and interactions with Māori students. Through the process of critical reflection upon the evidence presented in the narratives of Māori students and others, a professional learning conversation is created wherein teachers can make connections with their own experiences in similar settings. In this way teachers are provided with supported opportunities to discursively reposition in ways that: acknowledge their own mana and rangatiratanga; realise their own agency; and liberate their power to act.

RELATIONSHIPS and INTERACTIONS, that are fundamental to the culturally responsive

Effective Teaching Profile (ETP), are introduced at the Hui Whakarewa and STRATEGIES that can be used to develop culturally responsive learning contexts and learning conversations are modelled. The importance of detailed PLANNING to bring about change in classrooms, departments and across the school is promoted.

PSIRRPEG: The model for evaluating the professional development implementation

For the evaluation of the professional development implementation at the level of teachers in classrooms, the order of GEPRISP is reversed into PSIRPEG (the P is silent). Facilitators loop back through each of the elements within the model, in a continuous cycle. Facilitators focus target teachers on the need for PLANNING that will develop STRATEGIES to promote discursive INTERACTIONS that in turn will lead to quality and productive learning

RELATIONSHIPS with Māori students. Such relationships will reinforce teachers’ agentic

POSITIONING. Together these elements work towards improving Māori students’

EXPERIENCES and promote the GOAL of improving Māori students’ educational engagement, participation and achievement.

Module 2

4

G E P R I

Hui Whakarewa: 3 day induction hui

Goal

To improve

Māori students’ educational achievement

Experiences of Māori students in education are examined

Positioning of teachers, from deficit to agentic discourses is critical

Relationships that exist in classrooms need to be examined and may need to change

Interactions

Current ways of interacting in classrooms may also need to change

S P

Strategies are introduced to create opportunities for different ways of interacting

Plan

We need to plan for all this to happen

Creating new experiences for Māori students of being affirmed, valued and academically engaged

We continue to challenge teacher’s deficit positioning and promote agentic

positioning

Which develops new

relationships: a pedagogy of relations

Which support the use of different

interactions

New

strategies can be introduced

Cycle of In-class observations, feedback, co-construction meetings and shadow-coaching

Module 2

5

GOAL

We need to improve Māori student’s education achievement

G

So that we can all respond to the

GOAL of raising

Māori student achievement with greater confidence and improved results

Module 2

G

If we are to do this we need to examine

Māori students’ current educational

EXPERIENCES

Understanding the components of GEPRISP and PSIRPEG

The implementation and evaluation process

This may require us to challenge and/or affirm our own and teachers’

POSITIONING

We need to do this if we are to develop new kinds of

RELATIONSHIPS with Māori students

We need to develop new teaching and learning

INTERACTIONS in everyday classroom contexts

New interactions will be reinforced by learning new

STRATEGIES

E

In turn the changes we make will enhance and/or validate the

EXPERIENCES of

Māori students in our classrooms

E

P

Professional discussions and ongoing critical reflection will reinforce our

POSITIONING as agentic and therefore capable of bringing about positive changes for

Māori students P

R

…impact positively on our RELATIONSHIPS with students. This process may put pressure on or build new RELATIONSHIPS with colleagues as we seek to de-privatise our practise and continue to develop new skills R

I

…that will give rise to more effective teaching and learning

INTERACTIONS.

More effective teaching and learning interactions are likely to …

I

S

…to develop and use specific

STRATEGIES (some already known and some new)…

S

We need to PLAN strategically for all this to happen

P

Using evidence from Māori students’ recent participation and achievement we can PLAN strategically by using evidence formatively….

P

6

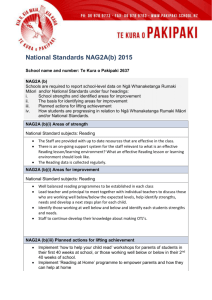

Section 4: PSIRPEG: Gathering evidence of the effects of implementation

When it is undertaken collaboratively PSIRPEG is useful as a means of evaluating the likely outcomes of planning. Teachers, facilitators, and school leaders are all supported to understand and apply the GEPRISP/PSIRPEG model. Those working in leadership roles will also be encouraged to use the acronym GPILSEO (Bishop et al.,

2009) to promote their own planning and implementation.

In order to evaluate the effects of the professional development implementation, evidence can be collected under each of the PSIRPEG headings, using a variety of qualitative and quantitative data gathering means.

PLANNING: Do teachers plan their lessons to create culturally appropriate and culturally responsive relationships and interactions in their classrooms?

Evidence of planning for classroom interactions is gathered using the observation tool. In addition, whole school planning may be promoted and led by the principal.

Changes in planning and the links between planning and delivery may then be examined.

STRATEGIES: Are teachers using new strategies to support their implementation of a culturally responsive pedagogy of relations in the classroom?

During the course of the classroom observation, facilitators record evidence of the use of discursive strategies in the classroom. Teachers should be able to demonstrate an increased range and type of co-operative and interactive strategies over the period of their participation.

INTERACTIONS: Are teachers engaged in developing new teaching and learning interactions?

Each term, Te Kotahitanga teachers are observed using the observation tool to examine changes in the teaching and learning interactions they have with Māori students. Over the period of their participation in Te Kotahitanga, teachers will be supported to interact more discursively with students. Discursive pedagogies mean that students will have more opportunities to actively engage in the construction of knowledge by talking about their prior experiences as the basis of constructing new knowledge. In this respect, learning can be said to be discursive or in the

conversations. While traditional transmission type pedagogies are not expected to be replaced, there will be more of a balance of interactions between these two pedagogies (transmission, discursive).

It is also expected that evidence of these changes will be systematically collected.

Evidence will include changes in: Māori students’ engagement with learning; work completion; Māori student and teacher interactions; proximity between the teacher and Māori students; Māori students’ involvement in power-sharing learning strategies; increase in the cognitive challenge of lessons and; evidence that Māori students are able to use their prior knowledge and experiences as an on-going means for developing new understandings within their classroom learning.

Module 2

7

RELATIONSHIPS: Are teachers engaged in developing new relationships with Māori students?

Te Kotahitanga teachers are observed using the observation tool to examine evidence of caring at three levels: manaakitanga, caring for Māori students’ wellbeing; mana motuhake, caring for and having high expectations of Māori students’ achievement; and ngā whakapiringatanga, teachers’ caring for the provision of well-managed learning environments in order for this to take place.

POSITIONING: Are teachers challenging their own discursive positioning so that they reject deficit theorising in regards to Māori student achievement and focus instead, on their own agency to make changes?

Teacher’s discursive positioning can be investigated by means of conversations, indepth interviews and surveys among a sample of teachers during their participation in Te Kotahitanga.

EXPERIENCES: How might Māori students’ educational experiences look now?

Māori students’ educational experiences may be systematically investigated by means of conversations, in-depth interviews, and surveys among a sample of Māori students during the project, to review their engagement and participation in learning and their identity as learners.

GOAL: What is the evidence of changes in student performance?

Where possible, evidence should be gathered of changes in Māori students’ performance in terms of changes to their participation in education: absenteeism, suspension, stand-downs, exclusions, retention rates, and their academic achievement.

Module 2

8

The Evidential Basis of Te Kotahitanga

G

E

P

R

I

S

GEPRISP

Goal: The need to improve Māori students’ educational achievement

Experiences: The need to examine Māori students’ educational experiences

Positioning: The need to challenge teachers’ discursive positioning

Relationships: The need to develop new relationships within teachers’ classrooms and pedagogies

Interactions: The need to develop new interactions with Māori students

Strategies: The need for new strategies

P

Planning: The need for effective planning so that all of this can happen

The Evidence

Measurable shifts in Māori students’ education participation and achievement

Shifts in Māori students’ thinking with an increase in their positive experiences

Shifts in teachers’ thinking from deficit to agentic positioning

Evidence of relationships of caring for

Māori students at three levels:

Caring about the wellbeing of learners

Caring about their achievement

Caring for the learning context

Shifts in interactions from traditional / transmission to active / discursive

Evidence of an increase in the range and type of cooperative and interactive strategies

Evidence of planning:

In-class

Amongst teachers

Middle leadership

Whole school

Principal leadership

Module 2

9

Evidential Basis of Te Kotahitanga through GEPRISP

G E P R I S P

Measurable increase in

Māori students' education achievement

Measurable increase in positive experiences for Māori students

Qualitative shifts in thinking from deficit to agentic

Evidence of relationships of caring at 3 levels: Caring, expectations and performance

Shifts in interactions from traditional to discursive

Evidence of increase in range and type of cooperative & interactive strategies

Evidence of planning:

In class

Inschool

Whole school

School systems

Module 2

10

Section 5: GEPRISP/PSIRPEG and the Professional Development model

The Te Kotahitanga professional development model, which supports the implementation of the ETP, is structured around the GEPRISP/PSIRPEG framework. The GOAL, the need to improve Māori students’ educational achievement, is both the beginning and end point of this model and remains at all times the central feature or kaupapa of Te Kotahitanga. For those participating in professional development as regional coordinators or facilitators, understanding Māori students’ educational EXPERIENCES is a prelude to their understanding how to challenge teachers’ discursive POSITIONING in relation to Māori students’ achievement. From these understandings the need to develop positive

RELATIONSHIPS with Māori students becomes apparent and conducive to supporting inclass INTERACTIONS and introducing STRATEGIES that will enhance learning outcomes for

Māori students. For this to take place, PLANNING is essential. PLANNING to incorporate discursive STRATEGIES into the classroom that will change teachers’ INTERACTIONS with students and vice versa, students’ interactions with each other, with their learning and thus with the curriculum. As a result of these changes, RELATIONSHIPS between teachers and students will change. Different relationships will affirm or challenge existing teacher

POSITIONING with regards to Māori students’ educational achievement which in turn will lead to changes in Māori students’ EXPERIENCES within the education system thus leading to the GOAL of raising Māori students’ achievement.

The professional development approach therefore is one where teachers and facilitators must also have planned opportunities to develop their own relationships. On the basis of these relationships both groups can collaborate more effectively to co-construct mutually agreeable goals, outcomes, protocols and parameters for success. The provision of ongoing and informed feedback and coaching between teachers and facilitators requires facilitators to make frequent, regular visits to the classroom to model the type of relationships and interactions that are fundamental to the implementation of the Effective Teaching Profile.

In addition, working within classroom settings has provided mutual benefits to facilitators, to regional coordinators, to the Research and Development team and to teachers. Facilitators, regional coordinators and the Research and Development team have opportunities to further connect theory to practice. Teachers benefit from collaboration, critical reflection and collegial feedback. Importantly, the relationships and interactions that are fundamental to the professional development process are those that are being fostered in classrooms.

Facilitators, regional coordinators and the Research and Development team are guided by the same metaphors as guide effective relationships and interactions in the classroom.

Module 2

11

G

GOAL

What it is

This goal establishes the central purpose or the kaupapa of Te Kotahitanga. Concerted efforts to improve Māori

students' education achievement, to monitor these improvements and to reflect critically on them for future teaching and learning purposes, is central to all aspects of Te Kotahitanga including the professional development programme.

Kaupapa can loosely be translated as the topic, theme, agenda or strategy. From a Māori worldview, the kaupapa is understood as a systematic and collective process that involves many people at many different levels. It requires the commitment of all participants to ensure that at each level, a person or delegate is charged with the role and responsibility of ensuring that their part of the kaupapa is discussed and understood by all and in turn responded to or acted upon. Kaupapa is still used in the contemporary world, within a variety of forums conducted from within te ao Māori, as groups strive to seek consensus or general agreement around a central topic, or shared goal or vision.

Therefore, in Te Kotahitanga, teacher agency and effectiveness is improved when all participants are working collaboratively and consistently in order to support the kaupapa or the goal of raising Māori students’ achievement.

What informs it

Despite the provision of alternative language education settings, over ninety percent of 12 to 15 year old Māori students attend mainstream English-medium schools (Ministry of Education, 2005b).

In these settings, evidence from the 2004 school year shows that, in comparison to non-Māori students, the overall academic achievement levels of Māori students was again low, while their rate of suspension from school was 3 times that of non-Māori and they left school with less formal qualifications than did their non-Māori peers, (Male

26.9% Māori compared to 11.2% non-Māori; females 21.6% Māori compared to 7.9% non-Māori) (Ministry of

Education, 2005b).

These disparities between Māori and non- Māori have continued since they were first identified statistically over forty years ago (Hunn, 1960). Despite the best of intentions, when we interrogate ongoing national achievement and participation data, it is clear that we, as educators, have continued to perpetuate the status quo for many

Māori students.

What it looks like in practice

The goal guides all aspects of Te Kotahitanga. It is the kaupapa. As facilitation team members, you will interrogate all actions and interactions in Te Kotahitanga against this goal. The following question must be embedded in your practice: How will this action contribute to the goal of raising Māori student achievement? It must also be embedded in the practice of the teachers with whom you work.

To ensure the goal is prioritised in both theorising and practice, facilitators are encouraged to use the planning and goal setting templates from the Te Kotahitanga modules in their feedback to teachers, in their co-construction meetings and in shadow coaching. These templates explicitly ask teachers to articulate the connection between their proposed actions and the goal of Te Kotahitanga.

Helping teachers to understand explicitly how their actions contribute to the goal of raising Māori student achievement, to monitor these improvements, and to reflect critically on them to inform future teaching and learning is a key task of facilitators.

Module 2

12

E

EXPERIENCES

What it is

Māori students’ authority and expertise about their own educational experiences, together with the experiences of their parents and whānau, their teachers and principals informed and shaped the direction of Te Kotahitanga Phase 1. Some of these educational experiences appear in Culture Speaks

(Bishop & Berryman, 2006). These combined experiences have continued to inform all subsequent phases of Te Kotahitanga. Throughout subsequent phases of Te Kotahitanga, further evidence has been collected about the educational experiences of Māori students and their teachers.

What informs it

Te Kotahitanga Phase 1 demonstrated that teachers who were responsive to Māori students’ experiences and perspectives of education were able to better facilitate Māori students engagement with learning from the perspective of Māori students’ own cultural experiences. These teachers created learning contexts whereby Māori students were able to interact with teachers and others in ways that they could bring themselves and how they make sense of the world to their classroom interactions

(Bruner, 1996). Bruner defines this as being able to use their own “cultural tool kit”.

Fundamental to this notion of authorising student perspectives is power (Bishop & Glynn, 1999). When power is shared by those who currently maintain control and dominance (teachers) over others

(students), then those in powerful positions will better understand the world of the “others”. (Refer to

Exercise 1, p.14)

What it looks like in practice

In the process of setting both individual and group goals in feedback and co-construction meetings, facilitators must urge teachers to critically consider the likely impact of their goals on the experiences of

Māori students. Is the teaching being done to students by the teacher or are all, teachers and students, a part of the teaching and learning process?

As teachers have greater consideration for the educational experiences of Māori students and become more responsive to their students, it is likely that their classroom practices will become more culturally responsive and discursive. The incorporation of student surveys and interviews into their planning and teaching could further inform this process providing these are undertaken in ways that protect the confidentiality of students.

Module 2

13

Exercise 1: Authorising Student Voice

Part A.

In groups, discuss what you think is meant by authorising student voice. Record your ideas below.

Part B.

Cook-Sather (2002) identified from a wide-ranging review of the literature:

“The work of authorising student perspectives is essential because of the various ways that it can improve educational practice, re-inform existing conversations about educational reform, and point to

the discussions and reform effects yet to be undertaken” (p.3). She further identified from the literature that authorising students’ perspectives was a major way of addressing power imbalances in classrooms in order that students’ voices could be heard and have legitimacy in the learning setting.

Cook-Sather (2002) identified that authorising of students’ experiences and understandings can:

• directly improve educational practice because when teachers listen to and learn from students, they can begin to see the world from those students’ perspectives (Clarke, 1995; Davies, 1982; Finders,

1997; Heshusius, 1994)

• help teachers make what they teach more accessible to students (Commeyras, 1995; Dahl, 1995;

Davies, 1982; Lincoln, 1995; Johnson & Nicholls, 1995)

• contribute to the conceptualisation of teaching, learning, and the ways we study them as more collaborative processes (Corbett & Wilson, 1995; Nicholls & Thorkildsen, 1995; Oldfather & Thomas,

1998; Shor, 1992)

• make students feel empowered when they are taken seriously and attended to as knowledgeable participants in important conversations (Hudson-Ross, Cleary & Casey, 1993)

• motivate students to participate constructively in their education (Colsant, 1995; Oldfather et al.,

1999; Sanon, Baxter, Fortune & Opotow, 2001; Shultz & Cook-Sather, 2001).

Discuss the concept of authorising students’ experiences alongside these findings. Use the recording sheet on the next page to respond.

Module 2

14

Exercise 1: Authorising Student Voice - Recording Sheet

Authorising students’ experiences in New Zealand classrooms.

Consider your experiences as students in light of the research findings on the previous page. Record your responses / ideas.

Consider your experiences as teachers of Māori students in light of the research findings on the previous page. Record your responses / ideas.

What sense do you make of this?

How might you apply the above conclusions?

Reflection

In your reflection journal record your responses to the following questions:

What has this activity contributed to my theorising about Māori students?

How has this activity contributed to my theorising about Te Kotahitanga?

What implications does this have for my practice?

What will I do differently?

Module 2

15

P

POSITIONING

What it is

Positioning in terms of Te Kotahitanga refers to one’s discursive positioning in terms of Māori students’ educational achievement. Te Kotahitanga seeks to support teachers to theorise from within discourses of agency (agentic positioning) rather than from within discourses of deficiency (deficit theorising).

What informs it

The analysis of the narratives of Māori students, and those of their parents, teachers and principals in

Phase 1 revealed a clear picture of conflicts in theorising or conflicts in explaining the lived educational experiences of Māori students.

The discursive viewpoint of the majority of teachers in Te Kotahitanga Phase 1 suggested that the major influence on Māori students’ educational achievement was the children themselves and/or their family/whānau circumstances with systemic/structural issues placed second. Many teachers felt powerless (non-agentic) to effect positive change in their classrooms until these major influences, impeding Māori students’ learning, were resolved. This position was characterised by discourses of deficiency. The Māori students, those parenting these students and their principals (and some of their teachers) saw that the most important influence on Māori students’ educational achievement was the quality of the in-class, face-to-face relationships and interactions between teachers and Māori students.

Solutions that seek to fix up perceived deficiencies in others emerge from a functional limitation paradigm (deficit theorising). An ecological paradigm looks for solutions at the interface between teachers and learners. The key is in teachers taking personal and professional responsibility to seek solutions from within positions of agency (agentic positioning), rather than abrogating responsibility to change.

What it looks like in practice

The challenge to teachers’ discursive positioning in regards to Māori students’ educational experience forms the essential element of the first day of the Hui Whakarewa. Te Kotahitanga has shown that the key to improving Māori students’ achievement is professional development that places teachers in non-confrontational situations where, by means of authentic yet vicarious experiences, they can critically reflect upon their own theorising and the impact that deficit theorising has upon Māori students’ educational achievement.

This professional development requires teachers to be supported to change their theorising from discourses of deficits to discourses of agency and then their re-positioning within these alternative discourses, both in practice and in theory.

The development of a school-wide means for teachers to reflect collaboratively upon their changing practices and theorising, in the light of a range of student participation and achievement evidence, supports, reinforces and sustains this agentic positioning.

Module 2

16

Exercise 2: Recognising deficit theorising

Part 1: Sort the following statements into agentic and non-agentic discourses and paste them under the appropriate heading on the accompanying recording sheet. Explain why you have placed them where you have.

“I’ve tried everything I know. His attitude is really uncooperative.

How do you others find him in class?”

“I’m really worried about John. He very rarely contributes and often opts out. Can anyone give me any suggestions?”

“It would be a good start if he came to school with the gear he needs. He’s never prepared for lessons. He’s got no support from home! I’m sick of it!”

“The trouble is he’s got an attitude. His big brother was the same

– insolent and aggressive.”

“I just can’t seem to get to know him. He’s often surly and unresponsive. Anyone know anything about his interests that might be a starting point for me?”

“He can’t stay focused for more than a few minutes at a time. No discipline from home, I’d say.”

“He’s plain lazy – that’s his problem.”

“Tama really struggles to get anything down on paper. I thought I could use a doughnut to help with written work preparation.

What do you think?”

Part 2: Under the appropriate columns, add statements that you have heard in your school.

Module 2

17

Exercise 2: Recording sheet

Non-agentic / Deficit theorising Agentic

Module 2

18

Exercise 3: Responding to deficit theorising

The following are authentic deficit responses collected from facilitators in Te Kotahitanga

Phase 3. How could you feedback in a way that is respectful of all but does not dodge or ignore the pathologising that is occurring.

“He can’t keep up. He doesn’t have the skills. What do they do at primary school? Kids shouldn’t be coming to secondary school illiterate and without basic Maths skills.”

“Oh her ….hmpf.. her sister was a pain.”

“I know we’re not supposed to deficit theorise but John’s attendance is really awful and it doesn’t seem to matter what I do. I’ve heard that there are just not the right role models at home.”

“He just doesn’t care about school.”

“Oh, I love Māori students but they come from such difficult backgrounds.”

“You know the biggest problem is the scheme. We have to study such irrelevant stuff. It doesn’t mean anything to them.”

“Year 10s have a real attitude problem. I don’t think we’re going to get far until we make some changes to the way we organise the form rooms.”

“It doesn’t matter what I do, I can’t get through to her. I think she’s given up.”

Reflection

In your reflection journal record your responses to the following questions:

What has this activity contributed to my theorising about Te Kotahitanga?

What implications does this have for my practice?

What will I do differently?

What will our team do differently?

Module 2

19

R

RELATIONSHIPS

What it is

Relationships are the interpersonal links between teachers and students, both within the classroom context, and within the broader school context. Effective teachers of Māori students demonstrate on a daily basis that above all else, they care for Māori students and their cultural identity. Māori students’ voices have made it clear that this is a fundamental prerequisite for effective teachers, a base from which all other characteristics of the Effective Teaching Profile can flow.

What informs it

Effective teachers of Māori students demonstrate on a daily basis that: a) they positively and vehemently reject deficit theorising as a means of explaining Māori students’ educational achievement levels, and b) they know and understand how to bring about change in Māori students’ educational achievement and are professionally committed to doing so. Effective teachers of Māori demonstrate caring at three levels:

caring for the learner’s wellbeing (manaakitanga)

caring about their achievement (mana motuhake)

caring for the learning contexts (whakapiringatanga)

Effective teachers of Māori students:

care for Māori students as culturally located individuals

demonstrate high learning expectations

demonstrate high behaviour expectations

provide a well-managed learning environment

create culturally appropriate contexts for learning

create culturally responsive contexts for learning

What it looks like in practice

Evidence of relationships between individual teachers and their Māori students is one aspect of the term-by-term in-class observations. Facilitators assist teachers to understand and reflect on the evidence about their relationships with Māori students by providing specific feedback to teachers based on the evidence generated from their classroom observations. Individualised feedback then provides the basis for goal setting, group co-construction and shadow coaching.

When developing individual and group goals through feedback and co-construction meetings teachers are asked to consider the impact of their proposed goal on their relationships with the Māori students they teach.

Module 2

20

I

INTERACTIONS

What it is

Effective teachers of Māori students, demonstrate on a daily basis, a range of effective, traditional to discursive, teaching and learning interactions. These interactions form an essential part of the

Effective Teaching Profile.

What informs it

Teachers remain dominant in classrooms mainly by creating teaching contexts of their own cultural design, and by constructing what Young (1991) terms traditional methods. Young suggests that it is the context created in such classrooms by teachers that allows them to maintain power over such issues as: who initiates learning; who benefits from the education; whose world views will be represented; and with what authority and to whom are they accountable? (Bishop, 1996).

Walker (1973) identified as early as the 1970s that power imbalances, rather than just the

Eurocentric, mono-cultural status of teachers, impacted negatively upon Māori children’s learning.

Walker’s findings challenge existing notions of addressing educational disparities, through teachers addressing their own cultural learning or by merely utilising a greater range of strategies. Instead,

Walker’s findings challenge educators to consider the part power imbalances play in their relationships and interactions with students and to attempt to address this aspect.

In Te Kotahitanga the interactions that Māori students said would help them engage with learning have been used to inform our practices. Students suggested that mutual benefits would emerge when teaching and learning roles were shared (ako). Students also said that as well as traditional teacher directed transmission type learning opportunities they wanted times when they could co-construct and even direct their own learning processes. Evidence of student outcomes, in classes where teachers took on board their suggestions for more discursive and interactive strategies, indicated that they were correct.

What it looks like in practice

Facilitators assist teachers to understand and reflect on evidence from in-class interactions by providing specific feedback to teachers based on the evidence generated from their classroom observations. Individualised feedback then provides the basis for goal setting, group co-construction and shadow coaching. Facilitators also provide specific feedback based on this evidence to assist teachers to move from traditional to discursive practices.

Individualised feedback, goal setting, group co-construction and shadow coaching are specific opportunities for teachers to plan to build on students’ prior cultural experiences, provide appropriate feedback and feed-forward and co-construct learning with students. These interactions are fundamental to developing power-sharing relationships.

Module 2

21

S

STRATEGIES

What it is

Te Kotahitanga acknowledges that effective teachers maintain a wide repertoire of teaching and learning strategies that assist them to create culturally appropriate and responsive contexts for learning.

What informs it

Teachers’ choice and use of strategies can clearly signal to Māori students that they: a) care for their Māori students as culturally located human beings; b) care about the performance of their Māori students; c) are competent, well-prepared teaching and learning professionals.

Teachers can be more effective when they understand the particular strategies they use, can theorise about why they are using them, and understand the potential effects of these strategies on classroom and school dynamics.

What it looks like in practice

Through feedback, co-construction, shadow coaching and other professional development opportunities, teachers learn new strategies that they can incorporate into culturally appropriate and culturally responsive learning contexts. In no particular order, these strategies could include: a) narrative pedagogy b) Co-operative Learning c) using assessment for formative purposes d) student-generated questioning e) critical reflection f) meta-cognitive approaches g) differentiated learning h) reciprocal learning i) peer learning j) assessment for formative purposes

Module 2

22

P

PLANNING

What it is

Facilitators are required to work with teachers on an on-going basis in order to facilitate teachers’ ownership of Te Kotahitanga in their school. Teachers are required to develop new relationships with students and use a range of new interactions and discursive strategies. For some people this will require a paradigm shift. Change such as this must not be left to chance. Thorough and effective planning to bring about these changes is a necessity and a priority.

What informs it

The planned process for facilitating shifts towards more culturally responsive classrooms and more discursive teaching strategies involves: a) conducting a series of in-class observations to identify shifts in teaching interactions b) using observations as a basis for objective feedback, feed forward and co-construction with individual teachers c) providing feedback / feed forward and facilitating co-construction meetings with groups of teachers d) conducting follow-up, shadow- coaching sessions with individual teachers

Te Kotahitanga recognises the need for a planned means whereby teachers/groups/departments/schools can take ownership of the professional development process to ensure long-term sustainability. This is done through: a) capacity building of a lead facilitator b) capacity building among staff c) and the incorporation of RTLB and/or other educational advisors into the process.

Te Kotahitanga also recognises the need for a planned means whereby schools can identify the structural changes that are necessary to support in-class developments. Principals are assisted, through the use of

GPILSEO, to lead the reform in order to identify structural changes that are necessary to support in-class developments.

It is critical for schools to have a planned means whereby teachers / groups / departments / schools can know if they have made a difference in Māori students’ educational development. This is achieved by using assessment for both summative and formative purposes together with professional and historical school knowledge.

What it looks like in practice

Facilitators and teachers are asked to collect evidence of student participation. This may be in the form of student attendance records, suspensions, stand-downs, referrals and exemptions. Data should be used to inform future planning within the school itself.

Teachers are asked to bring evidence of Māori students’ achievement to co-construction meetings.

The shared analysis and interpretation of this evidence, and the ensuing collaborative goal setting and action planning, supports teachers to incorporate the Effective Teaching Profile and culturally responsive and relational contexts for learning into their daily classroom practice.

Module 2

23

Section 7

The synergy of the elements of GEPRISP

Te Kotahitanga provides a complex and dynamic set of interacting and interdependent factors that have collectively contributed to raising Māori students’ educational achievement. It is more useful to weave together this complexity than it is to attempt to deconstruct the complexity in pursuit of single or simple solutions. In other words, the answer to improving Māori students’ educational achievement lies in the synergistic relationships of a number of interacting factors where the combined results are greater than the sum of the individual components.

Koringoringo

The images that guide the professional development are those of koringoringo. They are spiraling and recursive in nature rather than sequential. As previously stated, the kaupapa of Te Kotahitanga is the goal of raising Māori student achievement and the belief that agentic teachers have the potential to make a valuable contribution in this. Given that the professional development must also be driven by this goal it follows that the GEPRISP component of the professional development must, by and large, be classroom and student based.

While the professional development role of the researchers, professional developers, regional coordinators and facilitators is about developing professionals

(about teaching), it is also about being open to learning in order to improve practice by engaging in discursive reflective dialogue with others. Within this model all participants (researchers, professional developers, regional coordinators, facilitators and teachers) work together, providing each other with support as ideas are shared and tested. Testing involves careful planning, monitoring and reflection upon the impact of the professional development on teacher positioning and thus on the goal of raising Māori students’ achievement.

Such an iterative approach first requires establishing relationships amongst the groups of people involved: researchers; professional developers; regional coordinators; facilitators; and teachers. Connections and understandings must also be made with the whakapapa or genealogy of Te Kotahitanga, and with the intricacies of GEPRISP and the Effective Teaching Profile. Researchers, professional developers, regional coordinators, facilitators, and teachers are then able to interact within this spiraling, dynamic, and multi-dimensional model of information sharing

(instruction and demonstration), followed by opportunities to apply their new learning in authentic but supported teaching and learning situations. Such an approach involves, where possible, the setting of mutually agreeable goals, outcomes and protocols as well as parameters for success such as time, procedures and opportunities for practice and reflection by all participants.

Module 2

24

Exercise 4: Reviewing GEPRISP

(narrative plus recording sheet)

Narrative for Te Kotahitanga Framework Review

As you deliver this narrative, participants record their ideas on the recording sheet on page 27.

You were introduced to GEPRISP as a framework for remembering the range of elements within Te Kotahitanga. This exercise aims to individually review the elements of GEPRISP and to consider their place in the training that your team will provide for teachers.

Remember your understanding of each of these elements is crucial to the success of the teachers you will be training as part of Te Kotahitanga.

1.

In the boxes underneath each of the elements write what each of the letters stands for.

2.

Move on to the next box. You will again see G for goal. In the space provided write in your own words your understanding of the goal of Te Kotahitanga.

Remember this is the goal. This is why we are all here. We are working towards this goal. This is the goal that you need to ensure your teachers will also be working towards. Don’t lose sight of it.

3.

Move on to E for experiences. Whose experiences and why are these experiences so important? What do these experiences help us to understand?

How do we pass these experiences on to our teachers? Write down your ideas.

4.

Now move on to P for Position. What do we know about positioning? Use the continuum to help you put down some of your ideas. There should be three different points. Add one to the middle and label all three. What is so important about each of these points? What did the narratives of experience tell us about where the different groups interviewed had positioned themselves? How does positioning affect the work of Te Kotahitanga? How will it affect your work?

Where do we need to be positioned in order to make an effective difference for

Māori students? What, in your opinion, is the most important thing about this element of the Te Kotahitanga framework?

5.

Move on to R for Relationships. How did we learn about this and what sits within this element? Write these ideas down. What can you remember about each one?

How could you explain this to others who have never heard anything about this project? What resources have the Professional Development team used that would be useful to help with your explanation? Who else could you use to support you with this element? What else do you need to know? What questions do you have?

6.

Now we should be ready to annotate around I for interactions. Think about each of the bullet points. These interactions, ordered in a range from traditional to more discursive teaching interactions, are what you have been identifying using the Observation Tool with teachers in your school. Write an interaction at each of the bullet points then briefly note what they look like. What do you know about the terms traditional and discursive? What important things did Māori students tell us about these types of interactions? Consider which interactions you have been seeing most frequently in your observations. What does having

Module 2

25

this information mean for your training? The Observation Tool gathers a wide range of information. What other pieces of information does it gather? Have a look at your notes. Is there anything else that you want to add? If there is put that down now.

7.

Move on to the S for strategies. Note down some of the strategies that you know will help your teachers become more discursive practitioners. Who in your area will be a good person to support professional development around a wide range of teaching and learning strategies? How could they be brought on board? Some of these strategies may also require teachers to change their existing classroom routines or seating plans. How might you respond to that?

8.

P is for Planning. How does this fit in to the total Te Kotahitanga framework?

What implications does this have to your training?

9.

Finally move to the top of the page, the arrows and the shading. Note the direction of the arrows and the boxes that are shaded in. Try and record in no more than three sentences or notes the significance of this.

10.

Reflection. In your reflection journal record your responses to the following questions:

What has this activity contributed to my theorising about Te

Kotahitanga?

What implications does this have for my practice?

What will I do differently?

What will our team do differently?

Module 2

26

G E P R I S P

G

P

E

R

C R C A

I

Observations

S

P

Module 2

27

References

Bishop, R. (1996). Collaborative Research Stories: Whakawhanaungatanga.

Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Bishop, R., & Berryman, M. (2006). Culture Speaks: Cultural relationships and

classroom learning. Wellington: Huia Press.

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Powell, A., & Teddy, L. (2007). Te Kotahitanga: Improving the educational achievement of Māori students in mainstream education

Phase 2: Towards a whole school approach. Report to the Ministry of

Education. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Tiakiwai, S., & Richardson, C. (2003). Te Kotahitanga:

Experiences of year 9 and 10 Māori students in mainstream classrooms. Final

Report to the Ministry of Education. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Bishop, R., & Glynn, T. (1999). Culture counts: Changing power relations in education.

Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Bishop, R., O'Sullivan, D., & Berryman, M. (2009 In Press). Scaling up Educational

reform: Addressing the politics of disparity. Wellington: New Zealand Council of

Education Research.

Bruner, J. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard

University Press.

Burr, V. (1995). An introduction to social constructionism. London: Routledge

Clark, C. (1995). Flights of fancy, leaps of faith: Children’s myths in contemporary

America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Colsant, L. (1995). “Hey, man, why do we gotta take this . . . ? ” Learning to listen to students. In J. G. Nicholls & T. A. Thorkildsen (Eds.), Reasons for learning:

Expanding the conversation on student-teacher collaboration (pp. 62–89).

New York: Teachers College Press.

Commeyras, M. (1995). What can we learn from students’ questions? Theory into

Practice, 43(2), 101–106.

Cook-Sather, A. (2002). Authorizing students’ perspectives: Towards trust, dialogue, and change in education. Education Researcher, 31, (4), 3-14.

Corbett, H. D., & Wilson, R. L. (1995). Make a difference with, not for, students: A plea for researchers and reformers. Educational Researcher, 24(5), 12–17.

Dahl, K. (1995). Challenges in understanding the learner’s perspective.

Theory into Practice, 43(2), 124–130.

Davies, B. (1982). Life in the classroom and playground: The accounts of

Module 2

28

primary school children. Boston: Routledge.

Durie, M. (1998). Te mana, te kāwanatanga: The politics of Māori self-determination.

South Melbourne, University of Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Finders, M. (1997). Just girls: Hidden literacies and life in junior high.

New York: Teachers College Press.

Heshusius, L. (1994). Freeing ourselves from objectivity: Managing subjectivity or turning towards a participatory mode of consciousness? Educational

Researcher, Vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 15-22.

Hudson-Ross, S., Cleary, L., & Casey, M. (1993). Children’s voices: Children talk about

literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Heineman.

Hunn, J.K. (1960). Report on the Department of Māori Affairs. Wellington:

Government Print.

Johnston, P., & Nicholls, J. (1995). Voices we want to hear and voices we don’t.

Theory Into Practice, 43(2), 94–100.

Lincoln, Y. (1995). In search of students’ voices. Theory Into Practice,

43(2), 88–93.

Ministry of Education. (2005a). Educate ministry of education statement of intent

2005 – 2010. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2005b). 2004 Ngā haeata mātauranga, annual report on

Māori education. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Nicholls, J., & Thorkildsen, T. (1995). Reasons for learning: Expanding the

conversation on student-teacher collaboration. New York: Teachers

College Press.

Oldfather, P., & Thomas, S. (1998). What does it mean when teachers participate in collaborative research with high school students on literacy motivations?

Teachers College Record, 90(4), 647–691.

Oldfather, P., Thomas, S., Eckert, L., Garcia, F., Grannis, N., Kilgore, J. (1999). The nature and outcomes of students’ longitudinal research on literacy motivations and schooling. Research in the Teaching of

English, 34, 281–320.

Parker, I. (1992). Discourse dynamics: Critical analysis for social and individual psychology. London: Routledge.

Sanon, F., Baxter, M., Fortune, L., & Opotow, S. (2001). Cutting class:

Perspectives of urban high school students. In J. Shultz & A. Cook-

Sather (Eds.), In our own words: Students’ perspectives on school (pp.

73–91). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Module 2

29

Shields, C. M., Bishop, R., & Mazawi, A. E. (2005). Pathologizing practices: The impact

of deficit thinking on education. New York: Peter Lang

Shor, I. (1992). Empowering education: Critical teaching for social change.

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Shultz, J., & Cook-Sather, A. (Eds.). (2001). In our own words: Students’

perspectives on school. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies research and indigenous peoples.

London & New York: Zed Books Ltd. Dunedin, New Zealand: University of

Otago Press.

Timperley, H, Phillips, G., & Wiseman, J. (2003). The Sustainability of Professional

Development in Literacy - Parts One and Two. Auckland: University of

Auckland.

Walker, R. (1973). Biculturalism in education. In D. Bray and C. Hill (Eds.), Polynesian

and Pakeha in New Zealand education. Vol. 1, Auckland: Heinemann.

Walker, R. (1990). Ka whawhai tonu matou: Struggle without end. Auckland, New

Zealand: Penguin Books.

Young, R. (1991). Critical theory and classroom talk. Clevedon; Multilingual Matters.

Module 2

30

DVDs and other resources to be embedded in this module

REMOVE THIS PAGE BEFORE PRINTING THE MODULE

PLEASE CHECK THAT THE ONLINE ARTICLES BELOW ARE IN FACT FREE TO

DOWNLOAD

ARTICLES

SET

Lawrence, Dawn (2011 no. 3). “What can I do about Māori underachievement?”

Critical reflections from a non-Māori participant in Te Kotahitanga. Full text article available online at http://www.nzcer.org.nz/nzcerpress/set/articles/what-can-i-doabout-maori-underachievement-critical-reflections-non-maori-pa - www.nzcer.org.nz/nzcerpress/set/articles/what-can-i-do-about-maoriunderachievement-critical-reflections-non-maori-pa

DVD “Te Kotahitanga” (2006) formatted in 7 chapters G E P R I S P

Iti’s DVD on Discursive positioning / repositioning. A question framework to accompany this DVD is currently being developed.

PPT of above DVD

Module 2

31