E Kaveinga: A Cook Island Model of Social

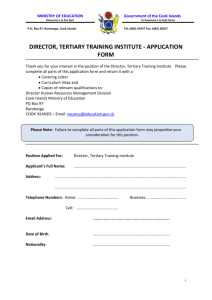

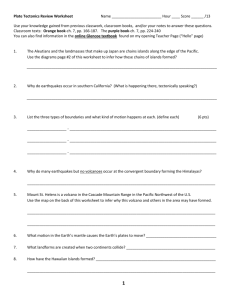

advertisement