Learning through Cross-Cultural Interactions:

advertisement

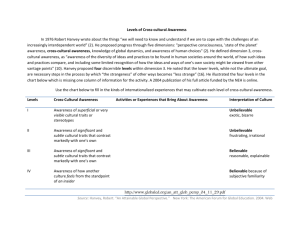

Xinquan Jiang & Marie Kendall Brown 1 Learning through Cross-Cultural Interactions: A developmental perspective on US and International Students Contemporary American society increasingly values international knowledge and understanding (Hayward & Siaya, 2001). A national survey conducted by the American Council on Education (ACE) showed that the American public overwhelmingly agreed to the importance of international knowledge and skills, and an increasingly diverse and complex worldview (Hayward & Siaya, 2001). Respondents further viewed higher education as a major source of international education opportunities. Colleges and universities have made educating for intercultural competencies and preparing for global citizenship an important educational outcome for their students (AAC&U, 2002; Guarasci & Cornwell, 1997). Further, many institutions have taken steps to create more diverse learning environments that are conducive to intercultural and international learning. One of the most common practices for creating a global experience on domestic campuses is the recruitment and enrollment of international students. The presence of substantial numbers of international students on campuses may benefit American students to the extent that it “brings the world home” to many undergraduates students who might not otherwise have the opportunity for firsthand exposure to different cultures and perspectives. Students benefit from direct interactions with international students through increasing knowledge of people from other countries and their cultures. Such knowledge and exposure to multiple, even competing, perspectives are important for promoting intellectual and moral development. As Gurin et. al (2002) note, the presence of diverse others and diverse perspectives, equality among peers, and discussion according to the rules of civil discourse are necessary conditions for fostering the orientations that students will need to be global citizens and leaders. These orientations include the capacity for perspective-taking, mutuality and reciprocity, accepting conflict as a normal part of life, the ability to perceive differences both within and between social groups, and a vested interest in the wider social world. While these benefits are widely recognized, few studies have examined the extent to which American students learn from interacting with international students. In fact, relatively little is known about what constitutes developmentally effective cross-cultural interactions and where and how such interactions occur. Background Literature International students have become an increasingly important source for internationalization and diversity for American colleges and universities. The Institute of International Education (IIE; 2006) reported that about 42% of 564,766 international students attending American higher education institutions were enrolled in undergraduate programs during the 2005-2006 academic year. Most international students came from Asian, especially India, China, South Korea and Japan taking the lead (IIE, 2006). The majority of international undergraduate students are traditional-aged college students who are financially supported by personal and family resources. They have traditionally been concentrated in academic fields such as business and engineering, but are increasingly entering the social sciences (IIE, 2006). Xinquan Jiang & Marie Kendall Brown 2 The presence of international students on American campuses enriches the learning experience of American students. A number of scholars have demonstrated that increasing the number of international students on campus is positively related to student engagement in diversity-related experiences and international understanding (Sharma & Mulka, 1993; Zhao, Kuh, & Carini, 2005). However, research on institutional structural diversity (e.g., how the presence of students and faculty of color affect informal and formal interactions across difference) has also found that simply increasing the number of students of color and international students does not by itself enhance student learning. Rather, as Hurtado (2007) points out “substantial and meaningful interaction (both informal and campus-facilitated) is central to the notion of how diversity affects learning” (p. 190). A number of scholars have noted that interactions between US undergraduate students and their international peers lack both breadth and depth (Sharma & Mulka, 1993; Zhao, Kuh, & Carini, 2005). In fact, a rather small proportion of US undergraduate students take advantage of the opportunity to interact with their international peers, and it is not clear to what extent those interactions are effective and meaningful. Conversely, international students are less satisfied with their social life and desire more opportunities to interact with their American peers. Interaction with faculty and peers has been identified as an important factor in facilitating international students’ academic achievement and personal development (Liberman, 1994; Stoynoff, 1997; Westwood & Barker, 1990). However, it has been suggested that interactions between international students and American students is frequently problematic due to language barriers and a lack of cultural awareness on both sides (Liberman, 1994; Pedersen, 1991; Schram & Lauver, 1988). International students often find themselves in social situations that elicit stress and anxiety due to cross-cultural differences (Kim, 2001). Stressful social situations can be ameliorated by establishing new friendship and social networks. Several individual and contextual factors, however, hinder international students from cross-cultural interactions, including lack of opportunities to interact with Americans, differences in culture and lifestyle, perceptions of disinterest from Americans, language difficulties, academic pressures, preoccupation with study, and cultural stereotypes and discrimination (Barratt & Huba, 1994; Rajput, 1999; Westwood & Barker, 1990). In fact, some international students forego a satisfying social life in order to focus on academic work. And, they may rely more and more on technology for interpersonal communication and social life (Zhao, Kuh, & Carini, 2005). It is also not surprising that many international students prefer the security of co-nationals for social support rather than dealing with the uncertainty of interacting with Americans. While some institutions have developed a variety of intentional intercultural learning programs to promote cultural awareness and meaningful interactions between international students and their American peers (Peterson et al., 1999), relatively few studies have examined the impact of international students and international education on American college campuses. As a group, college students tend to enter college with little experience interacting with culturally and ethnically diverse peers (Orfield, Bachmeier, Xinquan Jiang & Marie Kendall Brown 3 James, & Elite, 1997) and lack ethnic and cultural awareness and understanding (Hurtado, Engberg, Ponjuan, & Landreman, 2002; Saddlemire, 1996). The more specific question of how students learn through cross-cultural interactions and experiences is yet to be examined. This paper attempts to fill this gap by exploring cross-cultural interactions between US and international students that are considered developmentally effective in producing desired learning outcomes. Conceptual Framework Drawing upon constructive-developmental perspectives and Kegan’s (1994) notion of self-authorship, King and Baxter Magolda (2005) proposed a holistic developmental framework that describes how college students at varying levels of cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal development may approach meaning making with respect to intercultural interactions. The authors use the term intercultural maturity to describe the developmental trajectory of college students’ intercultural development. They argue that college students’ interpretations of their interactions with diverse others are developmentally grounded in their capacity for reflection and meaning making. Possessing less complex cognitive, intrapersonal, or interpersonal skills (i.e., less sophisticated levels of self-authorship) may interfere with college students’ capacity for developing intercultural maturity. Thus, the authors hypothesize that the developmental ability that is foundational to viewing individuals from other racial, ethnic, and cultural groups positively is grounded in the same ability that undergirds one’s ability to regard interpersonal differences favorably. We have chosen King and Baxter Magolda’s (2005) developmental model of intercultural maturity to ground this study because of its rigorous grounding in existing theoretical models of college student development, and because of its attention to elucidating the multifaceted dimensions of intercultural development. It presumes a complex interplay between how individuals construct difference in the world, how they function in intercultural situations, and whether they make sense of themselves as cultural human beings. Purpose The purpose of this paper is to investigate the extent to which college students engage in developmentally effective cross-cultural interactions. Baxter Magolda et. al (2007) define developmentally effective experiences as those that change the way a student sees or thinks about the world (the cognitive dimension), himself or herself (the intrapersonal dimension) and/or his or her relationships with others (the interpersonal dimension) in more advanced ways. Specifically, we will explore the developmentally effective (and ineffective) cross-cultural interactions and learning reported by American students with those of international students. We will also examine how student characteristics (country of origin, high school experience, international travel experience) and institutional contexts (density of international students, educational practices) contribute to effective cross-cultural interactions. The following research questions guide this study: Xinquan Jiang & Marie Kendall Brown 4 1. What are the features of American and international students’ cross-cultural interactions? 2. What are the characteristics of developmentally effective cross-cultural interactions? 3. What educational conditions and practices are effective in facilitating students’ crosscultural learning? Data Source and Analytic Methods This study used interview data collected as part of the cross-sectional pilot study of the Wabash National Study of Liberal Arts Education (WNSLAE), a four-campus mixed methods study designed to investigate critical factors that affect seven hypothesized outcomes of liberal arts education, including intercultural effectiveness. Each interview lasted from 60-90 minutes and was based upon an in-depth interview protocol that was designed specifically for the WNSLAE study by Baxter Magolda and King (in press) using a constructivist-developmental approach. The purpose of the interview was to elicit a clearer understanding of students’ meaning making about their college experiences. Interviews were conducted using an approach that incorporated both the “informal conversation interview” and “the general interview guide” (Patton, 1990, p. 228). For the purpose of this paper, we extracted from the interview transcripts all crosscultural interactions reported by US and international students. For US students, this includes interactions with non-American peers; for international students, a cross-cultural interaction is defined as an interaction with peers from a different country of origin. We then categorized the nature and characteristics of the cross-cultural interaction and coded it as either effective or ineffective. Developmentally effective cross-cultural interactions are defined as interactions that prompt a developmental change in the way a student sees or views the world, themselves, or their relationships with others that leads to selfauthorship. We developed an overall description of the data based on the recorded crosscultural interactions, student characteristics, and contextual information (Creswell, 2003). Sample The sample for this study includes all WNSLAE interview participants who were seniors at four-year institutions. We selected seniors because they are at the end of their college years and are well-positioned to reflect on their most significant collegiate experiences. The sample includes 60 students. Table 1 provides an overview of the sample characteristics. Although the sample is skewed in gender and country of origin, we felt that the overall diversity of the sample would illuminate the research questions noted above. [insert table here] Preliminary Findings Preliminary analysis has been completed on 19 interviews; the remaining analyses will be completed this summer. Two display matrices were created to assist in drawing descriptive conclusions about the data (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Each matrix for US and international students recorded the nature of each cross-cultural interactions and its impact on students, the developmental dimensions affected (i.e., cognitive, intrapersonal, Xinquan Jiang & Marie Kendall Brown 5 and interpersonal), the context in which the interaction occurred, and salient student characteristics. For US seniors, cross-cultural interactions fostered cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal development at different levels. Cognitively, students developed greater appreciation for different perspectives and were challenged to reevaluate their own values and belief systems. Students also gained more nuanced views of other cultures and people from different cultures. The opportunity to observe foreigners enabled them to reconsider previously held stereotypes about other cultures. Cross-cultural interactions also enabled them to gain new perspectives about themselves. Many US students reported a new found interest in international studies and/or international career aspirations. In the interpersonal dimension, US students with international experiences expressed appreciation and empathy for their international peers. As a result, they actively sought out more interactions with them. Cross-cultural interactions occurred in various contexts for US students. These included living with an international roommate and going abroad for various purposes (e.g., study abroad, internships, and traveling). Interestingly, students from rural communities greatly valued the presence of international students on campus. For international students, cross-cultural interactions fostered significant cognitive development. Specifically, students gained greater awareness of both American and international issues. Cross-cultural interactions facilitated students’ learning about American culture, its higher education system, and US racial and ethnic relations. Students also reported gaining a broadened understanding of global issues such as world politics and social justice. Cross-cultural interactions also influenced international students’ interpersonal development. Interacting with both domestic and co-national peer groups facilitated students’ adjustment to American higher education. Interactions across differences forced students to reconsider racial and cultural stereotypes. On the other hand, some students reported frustration at US students’ lack of world mindedness and disinterest in other cultures. In the intrapersonal dimension, cross-cultural interactions strengthened students’ sense of cultural identity and confirmed their own belief systems. Obviously, the American higher education system provided the primary context in which cross-cultural interactions occurred. Within that context, residential living, on-campus employment, interracial relationships, and campus community service organizations were cited as significant milieu for cross-cultural learning. Implications Understanding the impact of the presence of international students on college campuses and to what extent students learn from cross-cultural interactions have implications for educators, researchers and institutions. Institutions and educators can arrange educational experiences and contexts in ways that not only promote cross-cultural interactions but also engage international and American students in meaningful interactions that facilitate intellectual and personal development. Xinquan Jiang & Marie Kendall Brown 6 References Adelman, M. B. (1988). Cross-cultural Adjustment: A Theoretical Perspective on Social Support. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 12(3), 183-204. Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2002). Greater expectations: A new vision for learning as a nation goes to college. Washington, D.C.: Author. Barratt, M. F., & Huba, M. E. (1994). Factors related to international undergraduate student adjustment in an American community. College Student Journal, 28, 422436. Baxter Magolda, M., & King, P. M. (In press). Constructing conversations to assess meaning making: Self-authorship interviews. The Journal of College Student Development. Baxter Magolda, M.B., King, P.M., Stephenson, E., Kendall Brown, M.E., Lindsay, N.K., Barber, J.P., & Barnhardt, C. (2007, April). Developmentally effective experiences for promoting self-authorship. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association National Meeting. Chicago, IL. Bochner, S., Hutnik, B. M., & Furnham, A. (1985). The friendship patterns of overseas and host students in an Oxford student residence. Journal of Social Psychology, 125, 689-694. Creswell, J.W., & Plano Clark, V.L. (2006). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Guarasci, R., & Cornwell, G.H. (1997). Democratic education in an age of difference: Refining citizenship in higher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Hayward, F. M., & Siaya, L. M. (2001). Public experience, attitudes, and knowledge: A report on two national surveys about international education. Washington, D. C.: American Council on Education. Hurtado, S. (2007). Linking diversity with the educational and civic missions of higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 30(2), 185-196. Hurtado, S., Nelson Laird, T., Landreman, L., Engberg, M., & Fernandez, E. (2002). College students’ classroom preparation for a diverse democracy. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Association of Educational Research, New Orleans. Institute of International Education. (2006). Open Doors 2006: Report on International Educational Exchange. New York: Institute of International Education. Kang, T. S. (1972). A foreign student group as an ethnic community. International Review of Modern Sociology, 2, 72-82. Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Kim, Y. Y. (2001). An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. King, P. M. & Baxter Magolda, M. (2005). A developmental model of intercultural maturity. Journal of College Student Development, 46(6), 571-592. Liberman, K. (1994). Asian student perspectives on American university instruction. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18(2), 173-192. Orfield, G., Bachmeier, M.D., James, D.R., & Elite, T. (1997). Deepening segregation in American public schools: A special report from the Harvard project on school desegregation. Xinquan Jiang & Marie Kendall Brown 7 Patton, M.Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Pedersen, P. B. (1991). Counseling International Students. The Counseling psychologist, 19(1), 10-58. Rajput, H. J. (1999). Strangers in a strange land: Adjustment experiences of culturallyisolated international students., University of Minnesota, United States -Minnesota. Saddlemire, J. (1996). Qualitative study of White second-semester undergraduates’ attitudes toward African-American undergraduates at a predominantly White university. Journal of College Student Development, 37, 684-691. Schram, J. L., & Lauver, P. J. (1988). Alienation in international students. Journal of College Student Development, 29, 146-150. Sharma, M. P., & Mulka, J. S. (1993). The Impact of International Education upon United States Students in Comparative Perspective. . Stoynoff, S. (1997). Factors associated with international students' academic achievement. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 24, 56-68. Upcraft, M.L., & Schuh, J.H. (1996). Using qualitative methods. In M.L. Upcraft & J.H. Schuh (Eds.), Assessment in student affairs: A guide for practitioners, 52-83. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Westwood, M. J., & Barker, M. (1990). Academic achievement and social adaptation among international students: A comparison groups study of the peer-pairing program. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14(2), 251-263. Zhao, C.-M., Kuh, G. D., & Carini, R. M. (2005). A Comparison of International Student and American Student Engagement in Effective Educational Practices. Journal of Higher Education 76(2), 209-232. Xinquan Jiang & Marie Kendall Brown Table 1: Study Sample by Gender, Race/Ethnicity, Country of Origin, Citizenship Status, and Native English Speaker (N=60) Gender Male 22 Female 38 Race/Ethnicity* White 50 African American 1 American Indian 2 Asian 6 Latino/ Hispanic 3 Pacific Islander 2 Citizenship Status U.S.A. 46 U.S. Resident (Green Card Holder) 5 International Student 8 Other 1 International Students’ Country of Origin Canada 1 Ecuador 1 India 1 Japan 1 Singapore 1 South Korea 2 United Kingdom 1 Native English Speaker Yes 50 No 10 * Cell total exceeds 100% because respondents were asked to select their race/ethnicity from among several possible racial/ethnic categories, noting all categories that applied; some respondents marked multiple categories. 8