regional innovation systems - Universidade de Aveiro › SWEET

advertisement

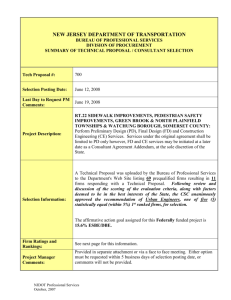

REGIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEMS - THE ANALYSIS OF THE PORTUGUESE CASE BASED ON THE TRIPLE HELIX CONCEPT Eduardo Anselmo de Castro Departamento de Ambiente e Ordenamento Universidade de Aveiro 3810- Aveiro- Portugal e-mail: ecastro@dao.ua.pt Carlos José Rodrigues Departamento de Ambiente e Ordenamento Universidade de Aveiro 3810- Aveiro- Portugal e-mail: cjose@dao.ua.pt Carlos Esteves Departamento de Ambiente e Ordenamento Universidade de Aveiro 3810- Aveiro- Portugal e-mail: cesteves@dao.ua.pt Artur da Rosa Pires Departamento de Ambiente e Ordenamento Universidade de Aveiro 3810 Aveiro- Portugal e-mail: artur@dao.ua.pt Abstract This paper contradicts the view which points out to the exhaustion of nation states and the elimination of space and territory as an effect of the increased trends of globalisation. The argument has its foundations in the evolutionary approach of economic development and states that the importance of national level grows within a globalised world driven by high levels of entropy. This entropy can be reduced through the emergence of national diversity based on different development paths of spatially defined regional economic systems, in which creativeness and selective capacity generate innovation and replication processes. The balance between innovation and replication underlies the dynamics of regional innovation systems, depending in turn on their internal coherence and ability to access external information. This theoretical framework is used to discuss the innovative capacity of Portuguese economy and to point out some solutions to overcome barriers to innovation. KEY WORDS: globalisation, diversity, selection, creativity, replication, innovation, regional systems, local governments, universities. 1. Introduction Globalisation is the outcome of three main factors which are releasing firms from physical distance constraints and from national regulatory frameworks: i) the significant decrease in transport costs; ii) the extraordinary development of telematics, which is the combination of telecommunication and information technologies; iii) the gradual removal of protectionist barriers to trade and to the circulation of capital. As a consequence it is often argued that globalisation is weakening nation states and eliminating the importance of space and territory as relevant dimensions of economic activity. Transnational firms can spread their activities around the world, creating subsidiaries and branch plants in the most convenient places, whilst there is also scope for the globalisation of SME´s. One of the most appealing imageries is that of virtual firms navigating in ciberspace, where the best suppliers and customers can be found and all types of business contracts can be made, no matter the geographical location and the size of partners. According to this view a globalised world is a very favourable 1 environment for footloose firms with an atomistic behaviour, only guided by individual self-interest and by the invisible hand of the market. Contradicting the point of view expressed above, it will be argued in this paper that such a global, delocalised and deregulated world, rather than favouring individual decision making and flexibility, will be a permanent source of uncertainty, informational bottlenecks and transaction costs. Using the theoretical framework of evolutionary economics, it will be also argued that this entropic world, rather than promoting innovation and economic dynamism, will push firms towards risk-averse routine behaviour and will increase the risks of technological lock-in. The argument will follow with the conclusion that the necessary reduction of the level of entropy cannot be undertaken by the simple functioning of markets. It will require instead the creation of other forms of institutional organisation influencing the relationships between economic actors and providing some guidance to their future action. In alternative to the concentration of this organisational role in the visible hands of a few giant transnational corporations (Chandler, 1977), released from any form of democratic control, public authorities must play an instrumental role to fulfil the requirements of order and organisation, defining policies and providing instruments of regulation and support of economic activity. Because the capacity to stay competitive in a globalised world is increasingly dependent upon the capacity to innovate and to absorb rapidly the innovations created elsewhere, a specific type of institutions is also required. These are the higher education and research institutions, which are responsible for the creation of the knowledge and competence background of the productive fabric. They are also responsible for the development of basic R&D activities and for the provision of technological guidance necessary to sustain innovation capacity. Firms, public authorities and academic/research institutions are the components of the triple helix, which is propelling the process of development. For an efficient operation of the triple helix mechanism a high degree of synchronism between its components is necessary, which in turn requires a strong social interaction between a multiplicity of individual and collective agents. This process of interaction is based on a common cultural background shared by the agents involved and implies the development of strong interdependencies based on mutual trust. As a 2 consequence, triple helices must be organised on a territorial basis, at different levels of aggregation, acting as the engines of national systems of innovation (Lundvall, 1992, Freeman, 1995) and of regional systems of innovation (Cooke, 1992). If, for a given territorial level, one or two helices are weakly developed or poorly sinchronised, the interaction between the productive apparatus, the research and education system and the public authorities is seriously compromised. For example, the Portuguese case shows that the passive role of regional public authorities is not enough compensated by the action of central administration. Being vertically organised along sectoral departments, the policies implemented by central state tend to be insufficiently adapted to regional specificities and, moreover, the set of sectoral policies lacks regional coherence, thus being unable to generate synergies. After the discussion of the theoretical issues presented above, the paper ends with an application of the triple helix concept to the case of regional economies which are starting a process of economic upgrading and development of innovative capabilities, such as some industrial regions of Northwest Portugal. It will be argued that the upgrading process should be aimed at the development of the capacity to be a creative user of technology, which involves in particular the capacity to be an advanced user of telematics. Both capacities are strongly dependent on the synchronic movement of the three helices at regional level, a pre-condition for the success of the Portuguese effort to catch up. 2. DO SPACE AND TERRITORY STILL MATTER? Globalisation have been often highlighted to argue that the leading role of nation-states is being considerably weakened. At the same time it is often admitted that the arising of the global village is eliminating the importance of space and subduing regional specificities to the logic of global markets functioning according to a deregulated framework. 3 This point of view is rejected by authors like Kitson and Michie (1996). Recognising the existence of an increased globalisation trend and its negative impact on the economic performance of some countries, they argue that there is a need for a strong intervention of national governments in order to maintain and improve economic performance: “rather than government intervention having become outdated, it may be that to see through the necessary policy will require more farreaching and radical intervention on the part of national governments than would have been the case in the previous, easier circumstances” (Kitson and Michie, pp 2, 1996). A complementary opinion is supported by Cooke et al (1992) who introduce the concept of global localisation in order to underline the growing relevance of place and specialisation within the process of globalisation, thus highlighting the role of regional economic and governance level. In line with the view of these authors, it is suggest in this paper that the analysis of both national and regional institutional frameworks is fundamental to understand how modern capitalist economies, which are based on free enterprise and decentralised decision making and which are subject to a high technological dynamism, do not generate completely chaotic and unpredictable environments. The understanding of the mechanisms which sustain this precarious balance between decentralisation, dynamism and order is one of the main concerns of evolutionary economics. This balance is reflected in the following dichotomies: i) coherence – diversity; ii) innovation – stability; iii) selectivity – generation of diversity. As argued by Dosi and Orsenigo (1988), the invisible hand of the market, facing constant technical change in a rather complex environment, is not enough to maintain a growing and changing economic system into a necessary extent of order and organisation. A globalised economy in a completely free market, such as it is often described by media, rather than corresponding to a world of maximised efficiency will lead to a monotonous world of maximised entropy. This is a world where millions of individual actors move in all directions and contact with everybody in the virtual space, each actor performing something like the brownian movement of a microscopic particle inside a gas1. According to Dosi and Orsenigo, emergence of 1 It is known that the behaviour of a gas in equilibrium is quite poor in terms of information, since it can be described by only three parameters: pressure, temperature and volume. 4 order and reduction of entropy implies the creation of other forms of institutional organisation aimed at the governance of the relationships among economic actors. The authors admit that the dynamic coherence of an economic system facing technical change conditions results from “particular architectures of forms of regulation which define the functioning and the scope of markets in relation to the specific properties of technological paradigms, the prevailing forms of behaviour and expectation formation of agents, the structure of the interdependencies of the system, and, finally, to nature and interests of the institutions which plan an active role in the economy” (Dosi and Orsenigo, pp. 32, 1988). Dynamic coherence is then the outcome of a favourable institutional framework which, rather than being the simple cumulative result of decentralised decisions spontaneously taken by individual agents, is strongly influenced by policies developed by nation-states providing instruments of regulation, support and selection of economic activities. The organisation of economic activities in localised productive systems is also an important source of coherence. The social capital (Putnam, 1993) which is associated with locally consolidated institutional routines and social conventions can contribute to reinforce the role of regions in economic development. Morgan (1996a, 1996b) takes trust as an example and, considering it as a key ingredient of development, stresses out that it begins as a rather local phenomena. Coherence should not be obtained at the cost of reducing diversity. In a complex world where the ex-ante selection of the best economic and technical solutions is subject to serious miscalculations, the efficiency of the alternative mechanism of ex-post selection of the best fitted depends on the diversity of available solutions. On the other hand, because creativity is often arising from the recombination of already existent pieces of knowledge (Törnqvist, 1990), diversity is also an essential pre-condition for innovativeness. It can be argued that diversity is the simple outcome of sectoral variety, without any contribution of territorial specificities. However the combination of sectoral and territorial dimensions will generate a pattern much more heterogeneous (LEIDESDORF ……..) than it would be the case of sectoral specialisation being the only source of variation. The co-existence of different industrial districts specialised, for instance, in high quality garments, competing with each other, creating each own 5 design and, of course, using a common package of global information and knowledge, will enable a higher degree of competition and selection and, consequently, a superior evolutionary process, than a single, unified and footloose national industry. Transnational fashion companies competing in a globalised environment can be seen as an alternative source of variation, much more powerful than industrial districts. However, the functional division of labour underlying the extensive networks of subcontracted companies organised by transnational companies is based on the specific capabilities of each location, reinforcing regional variation and inequalities, rather than eliminating them (Asheim and Dumford, 1997). In conclusion, there are strong reasons to think that nation states, rather than being pushed by the globalisation process to a marginal position, will keep an important role in the stabilisation of markets and in the definition of scenarios for future action. Simultaneously, regional specificities, in addition to their role as generators of coherence based on the share of a local social, cultural and technical background, are an important source of diversity, essential to feed the innovative process as well as for the operation of the ex-post selection mechanism. A good balance between coherence and diversity is also dependent on the ability of local authorities to adapt and to integrate horizontally the policies defined at the central state level in order to generate local synergies The territorial organisation of economic activities is an important means to keep the necessary balance between innovation and stability. In fact, in the absence of territorially based economic structures, the organisation of firms as members of giant global clusters according to a sectoral logic, would create a very heavy institutional environment with a strong inertia, and providing strong negative incentives to innovation. Firms forced to choose among thousands of suppliers and buyers, corresponding to a huge variety of productive solutions and product configurations and facing a high level of uncertainty about the outcomes of the different options, will almost certainly decide to minimise risks, adopting the old and already tested solutions. As Heiner (1988) explains, uncertainty reinforces routine behaviour rather than innovation. Conversely, the members of localised productive systems profit from an environment which reduces uncertainty. Sharing a common technical culture and knowledge basis as well as profiting from the existence of strong user-producer 6 relations (Lundvall, 1988), enabling the compatibility of innovations along the different phases of the productive chain, firms operate in an environment which stimulates innovativeness and non-routine behaviour. Assuming that innovation should be conceived as a process of interactive learning involving a broad institutional milieu (OECD, 1992), several authors recognise the adequacy of the regional level to set up a supportive environment for innovation (Morgan, 1996a, Cooke, 1994). Innovation is shaped by a wide range of institutional routines and social conventions which regulate economic life (Morgan, 1996b) and the balance between innovation and stability reflects the need to optimise the effects of creative effort. Creativity is a very scarce resource and research activities, based on the combination of multiple types of knowledge and competence and requiring frequently the use of sophisticated and expensive equipment are expensive and risky ventures. As a consequence, an innovative economy must be able to fulfil and integrate three different types of objectives: i) the selection of the main targets the innovative effort should attain; ii) the permanent screening of technological evolution at global level and the fast absorption of exogenous information and knowledge (Mowery and Oxley, 1995); iii) the consolidation of productive and organisational routines in the activities which will not be affected by important innovations, in order to maximise static efficiency. The capacity of firms to fulfil these three objectives is highly dependent upon the support provided by the local and national institutional environment and by the national and regional public authorities. It depends in particular on the support provided by learning system (schools, training centres, etc.), diffusing relevant knowledge and skills and the ability to use it, permanently renewing the knowledge and skill basis, and promoting technological diversity, the main raw material of evolution (Gregersen and Johnson, 1997). In which concerns de combined objective of selectivity and generation of diversity, territorial organisation plays also a key role. If a single firm, facing a globalised and de-localised environment, decides to innovate and develops an efficient solution, the diffusion of this innovation throughout the whole system appears to be rather problematic. Only giant firms which dominate the distribution channels and are powerful enough to launch global marketing campaigns would be 7 able to spread an innovation. In addition, if this innovation is really successful it can outcompete the alternative products and techniques. This, in turn, creates the risk of a long run technological lock-in. Much easier will be the diffusion of a successful innovation inside a smaller local productive system. Later on, this innovation, in the case of being really successful, can be spread nationally or even globally through a hierarchical bottom-up process2. The co-existence of several productive systems competing with each other, sometimes generating innovations and other times adopting exogenous technologies, will favour the maintenance of a reasonable level of product differentiation and technological diversity, thus decreasing the risks of lock-inn In conclusion, it can be said that the promotion of diversity and selectivity and the consequent balance between innovation and replication is strongly dependent upon the existence of regional systems of innovation with a higher degree of internal coherence and homogeneity and with a high capacity to absorb external information and knowledge. Coherence and homogeneity are local characteristics which affect the dynamic properties of regional productive systems, enabling them to compete in a globalised market. At the same time, competitive capacity depends also on the ability of regional systems to promote networking with the external world and on their capacity to adopt technical solutions generated elsewhere and to adapt them to local conditions. In other words, productive systems must acquire knowledge globally to think locally and a good capacity to think locally is a pre-condition to act globally. In addition to their fundamental role as generators of diversity, regional innovation systems must have the capacity to translate to the local context the policies defined at national level. In fact, the dynamics of regional systems, promoting cooperative behaviour directed to the exploitation of local synergies, to the horizontal co-ordination of activities, to the diffusion of information and to the definition of 2 Somebody with the uncommon family name Dobjansky, arriving to a big metropolis such as New York, is unable to spread his name and to transform it in a common one in the future, even if he succeeds to have ten or more children. Conversely, a very proliferous Dobjansky can rapidly disseminate his name in a small town and, if it happens to be the case that this small town starts a process of fast growth, inducing a very fast growth in the surrounding region, Dobjansky can be transformed into a very popular name in the long run. This example is adapted from Theodosius Dobjansky, quoted in Sagan and Druyan (1992) 8 development strategies, may be considered as a privileged means to minimise the limitations of national macroeconomic policies. According to Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff (1997) the institutional networking supporting regional innovation systems must form a spiral pattern of linkages, a triple helix intertwining the administrative chain of local or regional governments and their agencies, the productive chain made up of firms more or less organised along vertical and horizontal linkages and the techo-scientific chain of research and academic institutes. The concept of regional systems of innovation propelled by a triple helix networking engine can be applied to the particular case of economies based on traditional mature industries which are starting a process of economic upgrading and development of innovative capacity. It seems to be logic that such economies, rather than trying to compete in the most demanding so called high-tech sectors, should improve their capacity to absorb exogenous technical progress and to introduce incremental innovations in order to conquer market niches and to adopt process technology to their specific needs. It will be argued in the next section that this capacity to be a creative user of technology is strongly connected with the capacity to accede, select and use information and thus to the capacity to be an advanced user of telematics. This, in turn, requires the development of adequate regional innovation systems. 3. HOW REGIONAL INNOVATION SYSTEMS CAN PROMOTE THE CREATIVE USE OF TECHNOLOGY AND THE ADVANCED USE OF TELEMATICS. 9 INNOVATION IN PORTUGAL: IS A SYSTEMIC APPROACH FEASIBLE? Portugal has a long standing centralist tradition, and its administrative structure is based upon a strong central government, complemented by municipal governments endowed with a relatively high degree of autonomy. Regional government bodies are non-elected delegations of central state and regional specialised agencies are, in general, simple extensions of central departments, mainly performing bureaucratic tasks and showing very limited technical and financial capacities to undertake autonomous strategies. Are there regional innovation systems in Portugal which, in spite of the lack of strong regional powers, are able to generate autonomous innovative paths and to apply innovation policies adapted to the specificities of territorially based productive fabrics? Taking a simple definition given by Lundvall (1992), an innovation system “is constituted by elements and relationships which interact in the production, diffusion and use of new and economically useful knowledge”. Within this conceptual framework, a regional systemic basis for innovation should be considered as barely identifiable in Portugal. The lack of institutional co-operation and co-ordination which this conceptual framework implies can be highlighted as one of the main factors 10 hindering the development of regional innovation systems in the country. On the other hand, the weakness of the Portuguese regional innovation systems may also be associated with the prevailing characteristics of the socio-economic structure, which can be broadly summarised as follows: - lack of organisational and managerial capacities; - lack of awareness concerning the importance of intangible factors of competitiveness; - lack of an advanced technological basis; - scarcity of qualified labour force. These constraints are identified by several authors as pervasive factors hampering the development of innovation in Portuguese firms. The first two constraints are perhaps the most fundamental, an opinion shared by Simões (1996) who, in a technical report on innovation and management in Portuguese SMEs, concludes that the main barriers to innovation do not come out so much from a lack of technological capacity considered in a strictly sense, as from the limitations affecting entrepreneurial capacity, commercial management and learning. To this set of constraints, one should add the negative effect exerted by the financing system, lacking venture capital and hence avoiding to bear the risks inherent to innovative activities. A detailed empirical study developed by the authors under the scope of the European Union project REGIS- “Regional Innovation Systems- Designing for the Future”3, confirms the weaknessess of regional innovation systems in Portugal and validates the main hindering factors above referred. In Portugal, REGIS study focuses on the region of Aveiro, which is characterised by a relatively high level of industrial dynamics. The industrial fabric of Aveiro is made of a majority of small and very small firms, mixed with some medium and large firms, a few of them being branch plants of multinational corporations. They are mainly specialised in traditional sectors such as ceramics, metal manufacturing, footwear or cork products (much more than half of the cork stoppers of the world are 11 made in the region of Aveiro). Sectoral divisions are generally related to spatially concentrated homogeneous industrial clusters, revealing strong patterns of microspecialisation, stemming from a growing process based on replication of firms and forms of investment and complemented in more recent stages by the set-up of support activities. For example, the footwear industry is concentrated in a densely populated, semi-urban territory, with no more than 100 km2, where around 800 firms employ more than 30000 people. Most of these firms were replications created in the geographical neighbourhood of older ones by people who begun as employees and, after the acquisition of some technical expertise and market knowledge, have decided to start their own venture. As a consequence, one can detect geographical patterns of micro-specialisation, being some villages specialised in women footwear, others in children footwear and others in footwear components. Recently there is some evidence of upgrading, revealed by the growth of several supporting services and the appearence of some equipment manufacturers, reflecting an increasing division of labour and complexity of the economic fabric. In which concerns the innovative behaviour of firms, the results already obtained in REGIS project clearly show that organisational innovations are relatively scarce, while both product and process innovations tend to be incremental and are mainly aimed at the fulfilment of market requirements or at the resolution of very specific production problems. One can argue that the innovative effort of firms is mainly guided by a reactive response to external and internal factors, rather than by a pro-active attitude reflecting a strategy of gaining dynamic comparative advantages. Firms manage to maintain a set of regular clients and the sufficient turn-over to survive and, in general, their unique excellence goals are the accomplishement of delivery schedules and of product quality patterns. This can explain, on the one hand, the requirements of firms’ suppliers and customers as the main driving force for innovation, and, on the other hand, the low demand for technological or R&D services. 3 REGIS project, financed by TSER Programme (DG XII), is mainly aimed to evaluate to what extent innovation can be regarded as a regional systemic process. Eleven European regions with different socio-economic characteristics are being analysed by REGIS research team. 12 This type of behaviour is rooted in the characteristics of the industrial fabric. Firstly, there is a pattern of specialisation based on mature industrial sectors which are generally characterised by low or medium technological standards. The problems arising from sectoral specialisation are reinforced by the huge predominance of small firms, lacking the necessary critical mass to innovate. One should add the view that SMEs, trying to access information and knowledge to reduce uncertainty, have much more difficulties and proportionally higher costs than larger firms (CEC, 1996). An additional and pervasive barrier to innovation is the generalised lack of qualifications which affects both labour force and management. The poor academic background of managers, in most cases combined with their own image as self-made-men, explains another striking outcome of REGIS survey: the individualistic behaviour of firms, reflecting the lack of co-operation between themselves and between firms and innovation support institutions. When it occurs, co-operation generally assumes an adhoc and casuist type, based on informal contacts. Furthermore, these contacts are not regionally based, but geographically distributed by the two main metropolitan areas, Lisbon and Oporto, where the Portuguese economic and administrative structure is concentrated. Therefore, one can argue that the interactive learning process considered hereby as a key factor of an innovative environment is seriously affected. The individualistic behaviour evidenced by firms can be extended to support institutions, since the level of interaction between themselves is rather reduced or even not existing. On the other hand, co-operation with industry tends to be based on loose contacts aimed at the resolution of particular problems which occur mostly at a sectoral level. In general the managers of regional institutions interviewed by REGIS team do not acknowledge the existence of a regional innovation system and relate this with the top-down decision-making process, characteristic of Portuguese administrative tradition, and the consequent overwhelming dependency of the regional institutional structure relatively to the national techno-economic sphere. This dependency is evidenced in three different dimensions: firstly, the financial dependency on national (and European) funding provision, which exerts strong effects on organisational and strategic features and, in some particular cases (e.g. technological centres and R&D institutions), induces a project oriented behaviour, in which projects arise as a means 13 to have access to funding rather than as a means to reinforce a strategy; secondly, the technical dependency emerging from the lack of technical competencies within the region, giving rise to the resort to institutes located outside the region (mainly located in Lisbon or in Oporto); thirdly, the political dependency of regional agencies of national institutions, leading to the centralisation of policy and strategy definition in the capital city, though in different Ministries or central administrative bodies. The combination of these three levels of dependency raises severe difficulties to the establishment of a regional innovation system. The poor institutional basis combined with the lack of technical autonomy and the dependency on external financing sources and programmes, implies the acceptance of the policies which have generated them, hampering decisively the emergence of an interactive environment regionally focused. Moreover, the conflict between the vertical hierarchical structure depending upon central government and the relatively high degree of autonomy of certain regional institutions, such as Universities and industrial associations, gives rise to an almost absent horizontal co-ordination between the programmes and actions of different institutions. The summary of the conclusions drawn from REGIS survey lead us to assume that we are in presence of a regional productive/institutional fabric whose systemic dimension is rather weak, not to say that it cannot be identified. Hence there is no counterbalance to overcome the inefficiency of centralised policy making. In the light of these conclusions the potential advantages given by the geographical pattern of the productive system of Aveiro may become new barriers to innovation. According to the arguments presented in the previous sector, the combination of a diversified industial structure with a network of highly specialised industrial districts can be the basic ingredients for an economic system which is simultaneouly diversified and coherent, innovative and selective, creative and absorptive. However, in the context of Aveiro, the weakness of the institutional support, the lack of managerial and technical skills and the selfish tradition, create strong barriers to the circulation of information and to the development of a learning potential inside each industrial district and, moreover, prevents the building of bridges and the creation of synergies between the different districts. Thus, the economic system of Aveiro is made up of an amorphous set of industrial districts scarcely 14 related to each other, and with a poor level of internal organisation or, in other words, with a high level of entropy. Should this pessimistic view prevail or are there any windows of opportunity which can be open in order to induce a changing environment? In the following section, it will be argued that the weakness of Portuguese regional innovation systems, deeply rooted in the lack of strong regional powers, can be at least partially compensated by the combined action of municipal authorities, endowed with a relatively high level of autonomy, and Universities, a privileged centre of information and knowledge diffusion. 15 4. UNIVERSITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT: THE CASE OF AVEIRO The evolutionary path followed by local government and higher education institutions in the last decades has created the necessary potential to provide new opportunities to counteract the negative effects arising from the lack of a strong regional institutional basis. On the one hand, local governments in Portugal have been substantially reinforced after the revolution of April 1974, evolving from an almost total dependence upon central government and a rather limited technical competence4 to a legal status conferring them full administrative and financial autonomy. A significant extension of competencies was ratifyed, including their role in the promotion of socio-economic development. The gap which arose between the symbolic value and the actual consequences of this upgrading is becoming increasingly narrower, despite the strong centralist culture previling in Portugal (Mozzicafreddo et al, 1991). Municipalities, privileging the use of microeconomic instruments to promote socioeconomic development, namely through the planning, creation, maintenance and improvement of physical infrastructures, are emerging as a key actor within the public administration structure. On the other hand, most of the Portuguese universities are assuming new functions, which go far beyond the traditional teaching and research scopes. The debate about the external functions of universities is gaining growing relevance and, following global trends, raises new issues, such as, according to Charles (1997), the role of universities in the formation of human capital, as political agents within formal and informal local governance structures as well as their role as “regional embassies” of global innovation. In this context Portuguese universities are already undertaking initiatives which are deliberately directed to the strengthening of co-operation between the academic world and society, recognising the role that higher education institutions can play in providing and assisting regional/local development strategies (Pires, Rodrigues and Castro, 1997). 4 Before 1974 municipalities were simple an non-democratic controlling agents of central government decisions and conveyors of local economic interests (Mozzicafreddo et al, 1991) 16 However, local governments and universities are only a part of the “Triple Helix”. With the absence of the third element which is, in the case under discussion, a set of individualistic firms with a reduced willingness to network, what remains is a very crippled double helix. Then, how can this limitation be overcome? The new patterns of behaviour of local governments and universities combined with the low interactive capacity of industry seem to indicate that public and academic spheres should have a pervasive role to ensure that the missing helix is filled in, thus improving regional capacity to combine the three pairs of attributes upon which regional innovative capacity is dependent: coherence and diversity, competition and co-operation, codified knowledge and tacit techno-economic knowledge (Pires and Castro, 1997). The achievement of this role depends, on the one hand, upon the definition by universities of scientific and research programmes specially designed to tackle the needs of regional industry. It depends, on the other hand, upon the co-operative work between academia and local governments aimed at the dissemination of the information and knowledge generated by universities. Furthermore, academia and local authorities should act as institutions which shape the behaviour of economic agents (Dosi and Orsenigo, 1988), adverstising the need for an increased innovative mentality and undertaking concrete actions to promote the horizontal linkages among the whole regional institutional fabric, i.e., to foster an environment of institutional innovation. It is clear that this effort will be improved resorting to advanced telecommunication networks, considered as a basic precondition for the efficiency of social and productive systems and assuming an important role in improving both the internal coherence of productive systems and the external links essential to strengthen market power and to thicken the networks where information and knowledge are diffused. In this context, a number of initiatives are being carried out in the region of Aveiro, stemming from a co-operative framework established between the University of Aveiro and the local municipality. Two specific projects developing telecommunication networks, which are now in a preliminary phase, are briefly described below, trying to illustrate the synergies which can arise from a close co17 operative action of universities and local governments: the first corresponds to the elaboration of a regional masterplan of telecommunications, to be implemented by local authorities in partnership with other public and private institutions; the second is the creation and deployment of Internet based applications targeted to SMEs development needs. These two projects reflect to a large extent the coexistence, in the city of Aveiro, of a strong competence and scientific basis in the fields of telecommunications and urban and regional planning5. The regional master plan of telecommunications, has as starting points the need for improving the decision-making process and the co-ordination capacity of local authorities and, on the other hand, the need for a clear definition of the specific needs of firms and other economic institutions concerning the reception, selection, treatment and diffusion of information. The master plan will be designed to stimulate the local development of advanced telecommunication networks, triggering the initiatives of multiple agents and making compatible a multiplicity of interests and needs. It will include a viability study, assessing the consequences of different scenarios related to the greater or lesser likeliness of spontaneous supply of different services or sets of services as well as related to the possible roles of public institutions as promoters of those services which are more affected by high investment risks. One can argue that the innovative components of this project are twofold: firstly it is taking into account the specificity of economic institutions as potential users of advanced telecommunication services, commonly conceived as standardised infrastructures carrying on general purpose services; secondly, it will promote the coordination in terms of planning and decision-making, between different agents hitherto acting separately, namely telecommunication operators and local governments. The recognition of the need to take into account the specificity of each group of potential users of telecommunications is highlighted also in the second co-operative project, aimed at the creation and deployment of Internet based services targeted to regional SMEs requirements. The project’s background is added by the perception that the simple availability of telematic services, although necessary, is not a sufficient 5 The expertise stems from the location in Aveiro of the R&D centre of Portugal Telecom, complementing the knowledge capacity of the Departments of Electronics and Telecommunications and 18 condition for an efficient usage, which only emerges with improved skills and consolidated networks. As one can conclude from the previous section, regional SMEs, being the predominant type of firms within the region, tend to be characterised by low technological and informational content and by traditional methods of management, as well as by the lack of skilled labour. These features point out that advanced telecommunication services, once adopted, can be used much more as a means to improve the performance of routine tasks than as a lever to foster innovative capacity or to facilitate the search for new markets. In this context, one can argue that in order to improve competitiveness, a learning-to-use process is needed. On the other hand, SMEs generally do not have the necessary resources, competence and even time to access and process the key ingredient of competitiveness which is information. Taking into account this framework, four major objectives were defined: - to enable access to business information based on local and regional SMEs specific needs; - to improve the dissemination of information by local authorities, namely to reinforce local and regional networks; - to develop electronic commerce facilities targeted to the specific economic characteristics of SMEs; - to create Internet based tele-training facilities. The services will be provided by an operational centre which, under the aegis of the municipality of Aveiro, arises as an instrument for the co-ordination of local and regional key resources, gathering public, academic and private institutional spheres. of Environment and Planning of the University of Aveiro. 19 Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge the Directorate-General XII of the European Commission for the financing of REGIS project (TSER Programme) as well as the participating partners: Centre for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (University of Wales, Cardiff, UK), Department of Applied Economics of the University of the Basque Country (Bilbao, Spain), Catholic University of Louvain (Louvain-la-Neuve, Wallonia, Belgium), TNO Centre for Technology and Policy Studies (Apeldoone, The Netherlands), European Institute for Regional and Local Development of the University of Warsaw (Poland), Interuniversity Consortium for Cooperative Development Friuli (Udine, Italia), Faculty of Social and Economic Sciences of the University of Bamberg (Germany), Institute for Spatial Planning and Regional Development of the University of Economics (Vienna, Austria), Centre for Social Conflict Research of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Budapest, Hungary) and Work Research Centre of the University of Tampere (Finland). 20 References ASHEIM, B. and DUNFORD, M. (1997), Regional Futures, in Regional Studies, vol. 31, nº 55 (Special Issue on Regional Futures), pp 445-455. CEC (1996), Green Paper on Innovation, European Commission, CECA-CE-CEEA, Luxembourg. CHANDLER (1977), The Visible Hand - The Managerial Revolution of American Business, Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass). CHARLES, D. (1997), Universities and their Regions- Institutional Innovation and Changes in Governance Structures, in EUNIT Newsletter, Issue 5, March 1997. COOKE, P (1994), The Co-operative Advantage of Regions, paper presented in the Harold Innis Centenary Celebration Conference, University of Toronto (Canada), September 1994. COOKE, P., MOULAERT, F., SWYNGEDOUW, E., WEINSTEIN, O. and WELLS, P. (1992), Towards Global Localisation, UCL Press, London. DOSI, G. and ORSENIGO, L. (1988), Coordination and Transformation: an Overview of Structures, Behaviours and Change in Evolutionary Environments, in Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., Soete, L. (eds), Technical Change and Economic Theory, pp. 13-37, Pinter Publishers Ltd., London. GREGERSEN, B. and JOHNSON, B. (1997), Learning Economies, Innovation Systems and European Integration, in Regional Studies, vol. 31, nº 5 (Special Issue on Regional Futures), pp 479-490. HEINER, R. (1988), Imperfect Decisions and Routinized Production: Implications for Evolutionary Modelling and Inertial Technical Change, in Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., Soete, L. (eds), Technical Change and Economic Theory, pp. 148-169, Pinter Publishers Ltd., London. KITSON, M. and MICHIE, J., The Political Economy of Globalisation, paper prepared for the Euroconference on “The Globalisation of Technology or National Systems of Innovation?”, ISRDS, Rome, April 1996. 21 LEYDESDORFF, L. and ETZKOWITZ, H. (1997), The Future Location of Research: A Triple Helix of University-Industry-Government Relations, theme paper for a conference in New York City, January 1998. LUNDVALL, B.A. (ed.) (1988), Innovation as an Interactive Process: from Userproducer Relations to the National System of Innovation, in Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., Soete, L. (eds), Technical Change and Economic Theory, pp. 349-369, Pinter Publishers Ltd., London. LUNDVALL, B.A. (ed.) (1992), National Innovation Systems: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning, Pinter, London. MINISTÉRIO DA CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA (1997), Inquérito ao Potencial Científico e Tecnológico Nacional 1995, Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia, Lisboa. MORGAN, K. (1996a), The New Challenges to Collective Action in the Promotion of Local Development, lecture at the Encontro sobre Estratégias de Desenvolvimento e Financiamento Local, University of Aveiro (Portugal), October 1996. MORGAN, K. (1996b), The Learning Region: Why RTD is not Enough, paper presented in the 6th European Stride Conference, Bremen (Germany), March 1997. MOWERY, D. C. and OXLEY, J.E. (1995) - Inward Tecnology Transfer and Competitiveness: the Role of National Innovation Systems, in Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 19, nº 1, February (Special Issue on Technology and Innovation), p. 67-94. MOZZICAFREDDO, J. et al. (1991), Gestão e Legitimidade no Sistema Político Local, Escher, Lisboa. OECD (1992), Technology and the Economy: The Key Relationships, OECD, Paris OHMAE, K. (1993), The Rise of the Region State, in Foreign Affairs, spring, pp. 7887. PIRES, A.R. and CASTRO, E.A. (1997), Can a Strategic Project for a University be Strategic to Regional Development?, in Science and Public Policy, vol. 24, nº1, pp. 15-20. PIRES, A.R., RODRIGUES, C. and CASTRO, E.A. (1997), Universities Development Policy and Regional Innovation Systems, paper presented at the EUNIT 22 International Conference on Industry, Innovation and Territory, Universidade de Lisboa, March 1997. PUTNAM, R. (1993), The Prosperous Community: Social Capital and Public Life, in The American Prospect, no.13, pp. 35-42. SAGAN, C and DRUYAN, A. (1992), Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Portuguese Edition (1996), Gradiva, Lisboa. SILVERBERG, G. (1988), Modelling Economic Dynamics and Technical Change, in Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., Soete, L. (eds), Technical Change and Economic Theory, pp. 531-559, Pinter Publishers Ltd., London. SIMÕES, V.C. (1996), Inovação e Gestão em PME Industriais PortuguesasRelatório Técnico, GEP- Gabinete de Estudos e Planeamento do Ministério da Economia, Lisboa. 23