Ik zit even verder te denken over het paper dat ik kan maken

advertisement

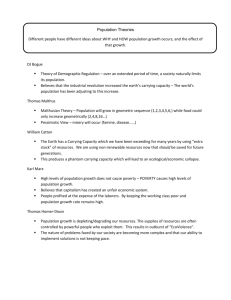

Complexity and carrying structures DRAFT learning-by-doing in urban planning Sybrand Tjallingii 1 and Gert de Roo 1 2 2 Delft University of Technology Groningen University Abstract Over the last thirty years one can observe a paradigm shift in urban and regional planning, or at least a shift in emphasis; from technical rationality to communicative rationality. Increasingly, we live in a continuously and rapidly changing world, full of uncertainties and unpredictable situations. In planning theory this has generated a transition from rational ‘objective’ systems’ thinking to interactive, inter-subjective planning process thinking. In the mean time, however, systems’ thinking evolved and has generated new approaches to chaos and complexity. This may bring new life to the academic debate about the possible interactions between technical and communicative planning traditions. This paper builds on these debates and confronts theoretical issues with experiences in planning practice, taking some Dutch urban planning cases as examples. Most practical planning situations are between the two theoretical extremes of technical and communicative rationales. In this ‘in between’ domain the paper focuses on two issues. The first issue concerns complexity and the stages of planning, from plan-making to planrealising and addresses the step-by-step process from vision generating to goals’ realising. The second issue is about complexity and the interaction between integrated and sector planning and addresses the conflicts between the search for synergism and sharp sector targets. We will emphasise here, the important role of objectifying conceptual tools in a learning-by-doing perspective of coping with complexity. The planning cases will illustrate the role of these tools that act as guiding models for the activities of planners and other actors in parallel planning processes. The guiding models discussed here illustrate their role in creating robust carrying structures as conditions for adaptive behaviour in two fields of planning. The first concerns urban water systems that can cope with the uncertainties of climate change. The second issue relates to non-linear spatial, economic and social transitions in the existing city. The conclusion part discusses possible implications for the interaction between complexity theory and planning. 1. Introduction Under the title The Question is Being or Becoming, De Roo (2009) confronts recent developments in complexity theory with planning theory. His reasoning leads to a scheme that positions technical rationality and communicative rationality on two sides of the spectrum (fig. 1). In recent decades, planning theory has developed two answers to the central issue of dealing with uncertainty. The first is the approach of communicative rationality, focussing on interaction in planning processes and inter-subjectively accepted interpretations of the planning situation. The second reaction emerges from the study of complex systems and combines chaos theory, adaptation and self-organisation with an evolution oriented approach to complex systems. In his paper, de Roo argues that complexity theory may have an important role to play in bridging the gap between the two extremes of rationality. The present paper will further explore the middle ground between the technical and communicative rationality. Most practical planning projects are muddling through this middle ground, combining technical substantive and communicative procedural issues. They try to avoid the pitfalls of unpractical sense and negotiated nonsense and seek to conceive strategies that build on the synergism of the two sides. Therefore, we will confront the theoretical debate with some practical experiences, widening the question from system-based Being or Becoming to the activity-based question of Doing. What may theory learn from practice, and how may it 1 guide practitioners through a world of complexity and uncertainty? QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Fig. 1. Between technical and communicative rationality (de Roo, 2009) As a first introduction we may briefly summarise a study about the methodology in Dutch municipal water plans (vandeVen & Tjallingii 2005, vandeVen et al. 2006). Some cities pioneered with municipal water plans since the early 1990s, but it was after the 2003 National Governance Agreement about Water that all municipalities were strongly encouraged to elaborate a co-ordinating water plan for their territory. Evaluating the first generation of these plans, the study distinguished three different approaches. 1. The target image approach. The basic idea is to agree about a blueprint of the future situation. The method focuses on testing measures for their efficiency to reach the target. The approach fits in the tradition of policy analysis and back-casting. Instrumental, technical rationality is the basis. Examples are the water plans of The Hague and Rotterdam that both combine ‘seducing’ images with precise ecological and chemical standards. 2. The guiding principle approach. The basic idea is to agree about a set of principles for development. The method focuses on the design of development strategies and physical conditions. A toolkit of guiding models, resulting from previous experiences of integrated planning is the basis for planning and design. The approach fits in the tradition of planning as social learning. Creating conditions and interaction are the basic elements. The water plans for Delft and Tilburg are examples. 2 3. The negotiating approach. The basic idea is bringing together the stakeholders and generating an interactive process that leads to targets and realisation. The method focuses on negotiating strategies. Communicative rationality is the basis. The approach fits in the tradition of planning as transaction. An example is the Almere water plan. At first sight the three approaches demonstrate a striking similarity with the dichotomy of technical and communicative rationality, described by De Roo and well known from planning theory literature. Obviously, the specific case of municipal water plans shows characteristics of a more general trend in both theory and practice. The approach of guiding principles and guiding models explores the middle ground and it is interesting to look at it more closely. How does this approach actually work in day-to-day practice? The Gorcum and Schalkwijk cases are good illustrations. Before turning to the theoretical debate these two cases will provide some concrete practical experiences. In the complexity discussion it seems that there are two options. First: a radical jump from object oriented systems approaches towards a process-oriented attitude. And second: improving the systems approach by integrating complexity research and adaptive planning. In this paper we will explore the middle ground between these two options by focusing on the interaction of technical and communicative rationalities in different situations illustrated by the two cases. 2. The Gorcum case planning situation Gorcum is a small city with 35.000 inhabitants in the area of big rivers of the Dutch Delta. The city was built at the mouth of a small river, the Linge, where it runs into the Waal, the large branch of the Rhine that passes Gorcum (Fig. 2). The area is on the southern fringe of the Randstad Green Heart where the pressure of urbanisation is high. The case concerns planning a new urban development of 1400 dwellings on the eastern fringe of the town and, more specifically, focuses on the role of water in the future development. As a consultant, the first author took part in the working party sessions devoted to these issues. Three stakeholder groups, three actors, participated in this stage of the planning process. actors and their discourses 1. The local government and private developers joined their efforts in a public-private development organisation. Their goal was to build houses. In their view the role of water is primarily to create a safe and attractive environment to enhance the quality of living in the new development. Naturally, the private developers wanted to make profit and also the local government welcomed a profitable project to generate the funds they needed for costly urban renewal projects in other parts of the town. For these actors, the most efficient means to achieve their goals is building more houses and make them more attractive. More space for surface water could be an option only, if more houses can be built. 2. The second actor is the waterboard, responsible for a safe and healthy surface water system. Their goals are specified objectives. The water level in the canals and ponds of the new area should not be less than 0.70 cm below street level. To this standard they add t = 10, meaning that a rainstorm occurring with a frequency of once in ten years could be tolerated to make the surface water rise above this level. The quality standards for surface water are: phosphate below 0.15 mg/l and nitrogen below 2.2 mg/l. The most 3 efficient means are also specific. To guarantee the water level of 0.70 cm a minimal surface of 10% of the built-up area should be designated for peak rainfall storage. The phosphate and nitrogen contents can be achieved by rinsing the system with the water of the river Linge that has phosphate and nitrogen levels slightly below the standard. This is common practice already for the adjacent existing residential area. 3. The third actor is the New Dutch Water Line initiative, whose representatives take part in the meetings. The goals of this organisation initiated by the National Government together with five Provincial administrations are related to the role of cultural heritage. The New Dutch Water Line is a 19th century defence line reaching from Amsterdam to south of Gorcum with fortresses and inundation works. Funds are made available to make this part of military and landscape history visible in future developments, such as the present plan for urban expansion of Gorcum. More specifically, the objective of this actor is to create conditions for a visible inundation event on “fortress day” a Saturday in September when the public is invited to visit all the New Water Line Fortresses and waterworks. The best means to realise this objective is to let in water from the river Waal near Fort Vuren, the place that was designed for the inundations. In the proposals put forward in the meetings of the working party on water planning, the three actors each followed their own technical rationality, based on the most efficient means to reach their own objectives. Communication was not easy because the developers talked in terms of economic stories, the water engineers presented their calculations and models and the Water Line representative was thinking and speaking in visible images. This is a more general barrier to learning and communication (Müller et al. (2005). Moreover, the plans of the actors in this case were not compatible. More houses do not fit in with the preferred image of the Water Line actor. Letting in water from the river Waal was rejected categorically by the water board because of the low quality of this water. guiding principles and guiding models At this stage of the planning process, that explores common grounds for integrated planning, the guiding principle approach played an important role. The actors shared principles of sustainable water management for health and safety and for the contribution of water in providing urban quality of life and enhancing landscape identity. There was a general agreement about the priority principle proposed by the State Committee on Watermanagement in the 21st Century: in urban water plans the first priority should be on-site retention, next comes storage nearby and only if rainwater has reached the river, discharge should be given priority (Commissie Waterbeheer, 2000). Agreement about principles is important, but the consensus remains rather abstract. To provide concrete guidance of planning and design processes a toolkit of guiding models has been developed and one of these seems to fit very well to the situation of this case: the circulation model (Tjallingii, 2007). The circulation model is a scheme for a robust carrying structure of an urban surface water system that can cope with extremes of too much and too little water. In this way the model creates conditions for addressing the complexity and uncertainty of climate change. In practice as in this case, the conceptual model guided the operational water models that produce precise calculations relevant for the technical objectives and the concrete dimensions of the plan. On the other hand the model also guided the design process, making the plan fit to the needs of the actors and to the ecological potential of the local landscape, as illustrated by Fig. 2. 4 The circulation model assumes on-site retention at the level of dwellings and streets but for the urban district level it focuses on creating rainwater storage in a small lake. This water is circulated through the surface water network of an urban area. Fluctuating water tables increase the peak storage and seasonal storage capacity. Storing rainfall peaks creates conditions for separating wastewater and rainwater. Seasonal storage creates a reservoir that is used in dry periods. Thus, the new system avoids both combined-sewer overflows and the summer-supply of polluted river water and in this way the circulation model effectively deals with the two most important sources of urban surface water pollution. By connecting the circulation system to the adjacent existing neighbourhoods the plan also creates conditions for disconnecting rainwater from the existing combined sewer system. This implies that in due time, also there the pollution problem of combined sewer overflows can be solved. Linge Outlet QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. weir New urban development pump Storage lake inundation area Helophytes Fort Vuren Waal Fig. 2. The circulation model and the structure of the water system for the new Gorcum development. The small pump in the circulation system continuously keeps the water moving, which is 5 good for water quality. A passage through a purifying wetland, the helophyte filter, is part of the system and can be designed for reaching the required phosphate and nitrogen standards. There is no more need for rinsing with external water, which is not a very sustainable idea anyhow. As the saying goes: dilution is no solution to pollution. On “fortress day”, in the Gorcum case, the weir on one side of the storage lake can be closed, and the pump on the other side supplies enough water from the system’s own sources to make the storage lake expand, inundating the adjacent meadows. There is no need to increase the number of houses, at least not for the financing of the plan. The storage lake in the eastern fringe of the plan will increase the value of the houses on the edge. As a whole the multifunctional nature of the plan creates conditions for multi funding and for public support from different actors. The guiding model generated a planning proposal that can fulfil the basic goals of the actors but not with the means they proposed. Rather than immediately looking for compromises between the proposals, the guiding model guides the actors to a deeper level, where it becomes possible to communicate between their basic needs and the basic potentialities of the ecosystem and the local landscape. This created a common language between the sector representatives and in the end, these actors agreed to the circulation-model-based spatial structure for the Gorcum development as a basis for further detailed operational planning and design. Summarising, the guiding model provided a tool for designing a robust carrying structure addressing both the complexity of climate change and the complexity of disagreement among the actors. 3. The Schalkwijk case In complex planning situations full of uncertainties, in the absence of clear cause and effect relations, one of the practical options is to start with a structure of the plan that creates basic conditions, a frame of carrying structures instead of a blueprint master plan. Water structures, as in the Gorcum case, are a good example. But, of course, urban planning is more than water planning. The Schalkwijk case may illustrate how water network structures can be combined with traffic network structures and how these two networks may act as carrying structures, providing a frame that allows for flexible infill in a socially and economically more complex planning situation (Fig. 3). planning situation Schalkwijk is a 30.000 inhabitants district of Haarlem built in the post-war period. It is a one-sided social housing area with predominantly rental apartments. As many of the apartment building developments of the same age, due to social and economic change the area threatens to slip into a downward spiral of unemployment, poverty and poor living conditions. A reconstruction and redevelopment scheme is well under way and the basic planning document is the 1999 Structure Plan. The spatial structure is based on the Two Networks’ Strategy, a guiding model that takes the networks of water and traffic as carrying structures for development (Tjallingii,1996, 2005). As in the Gorcum case, the guiding model stimulated the actors to discuss their ideas at a deeper level of needs and potentialities. In an early stage a residents’ festival generated seventy proposals that were used by working groups of public officials and private organizations for social, environmental and spatial issues in the plan. Van Eijk (2003) describes the details of the Schalkwijk communication process. In the context of this paper it is more relevant to focus on the way the Two Networks’ Strategy, as a guiding model, addresses complexity in this situation. 6 fast and slow lane dynamics All surveys demonstrate that most people highly value green spaces, but economically, parks and gardens are always less profitable than built developments. In the power play of urban development the quiet world of green spaces needs allies and water is an obvious candidate. Flood prevention and water supply are related to politically powerful issues such as safety, damage and health. Climate change increases the urgency to create space for water. Thus, the synergism of blue and green provides promising planning strategies for slow-lane environments. On the fast-lane side, the synergism of traffic and logistics creates an urban environment for dynamic activities, such as industry and commerce but also including intensified agricultural production and mass tourism. River Spaarne to motorway Storage lake Two Networks’ Strategy Fig. 3. The Two Networks’ Strategy and the Schalkwijk restructuring plan. On the map, the water is black. The arrows show where the road infrastructure gives access to the area. Together, the two networks create a robust framework that allows for flexible infill with a variety of projects for housing, shops, offices and public open spaces. It is not a blueprint of the future but it creates conditions. These conditions enhance the synergism of the activities on the fast-lane and slow-lane sides. The design of the framework should avoid conflicts between the dynamic and quiet sides. Guided by the strategy the Schalkwijk planning process led to the decision not to build a ring road in the urban fringe but to concentrate traffic, and slow down the speed, in the 7 central zone with most offices and the shopping mall. As a result, the fringe zone can become a quiet zone with a park, urban agriculture, interesting natural habitats for biodiversity. Here the storage lake and the wetlands with helophytes are positioned, the key elements in the water network. The circulation model also guided the design of the Schalkwijk water system From the storage lake, the water circulates through the built-up areas and then returns to the fringe. The redesigned fringe area greatly enhances the quality of the edge. Here, new houses were built for middle class incomes. Diversification of the housing stock is one of the social objectives. For those residents that improve their income, it creates possibilities to stay in the Schalkwijk area and move to the new houses on the edge with a very attractive view. Given the demand, investment and development is relatively easy. At the same time, also the lower incomes in the apartment buildings benefit from the presence of the green and quiet fringe zone. The quality-of-the-edge approach can also be seen in combination with green structure planning. A spatial structure of green spaces that follows the natural drainage pattern of small valleys and rivers, not only creates a blue-green network that enhances the identity of the city but also creates more edges with more quality. Research in many European cities has demonstrated the great potential of dynamic green structure strategies compared to static green belt strategies (Werquin, et al. 2005). In a process of urban sprawl many people jumped over the green belts to settle in the countryside and commute to the city, a process that has led to landscape fragmentation and traffic congestion in many urban regions. Creating attractive edges is a promising alternative, offering the proximity of both green and urban qualities. The future of urban development is not in the edge cities (Garreau,1992) but in the quality of the edge of the city. The two cases may illustrate a number of issues in the complexity and planning debate. The Gorcum case illustrates how a guiding model for water systems can play a role in bringing the discussions between different actors with different views to a deeper layer of fundamental needs and opportunities. This happened also in the Schalkwijk project. The description of this case throws more light on the role of a guiding model for urban development in general. The two networks create a frame for basic quality of flows and spaces and also provide a basis for adaptive decision making in the future. The two cases demonstrate the role of guiding models in both technical and communicative rationality as will be further discussed below. 4. Complexity, technical and communicative rationality a process perspective In the Gorcum case, the actors started with a goals and means perspective. The guiding model brought them back to basics, back to a stage in the planning process with more space for fundamental discussions about the long-term perspectives in this landscape at this stage of development. The communicative rationality addresses the complexity of disagreeing groups. But the instrument that plays a role in this communication process is a guiding model about the technical rationality of a carrying structure for long-term sustainable development. The guiding model generates answers to the complexity of climate change. So, in practice, communicative and technical rationality are inextricably bound up with each other. In a process perspective, the guiding model approach emphasises the priority of basic conditions over specific goals and means. This will only generate a basis for agreement, however, if the participants are able to link the basic conditions to their goals here and now. 8 The Schalkwijk case demonstrates the same issue of creating a common ground for different actors, but also highlights the role of carrying structures, creating a frame for adaptive planning decisions in the future. The complexity of uncertain future developments asks for conditions that create continuity with the urban landscape history, and thus identity. But at the same time there is a need for carrying structures that can cope with increasing traffic flows in uncertain network developments. The structure of the traffic and water networks generates a spatial plan that can play this role. In a process perspective, there is a need for step-by-step decision making, for no-regret decisions about a frame that leaves enough freedom for flexible future infill. Also here, we see an intimate link between communicative and technical rationality. Figure 4 illustrates different strategies to cope with complexity. In figure 4a we see an approach to planning processes that is increasingly popular and is inspired by the New Public Management (Hood, 1991). It is based on a solid belief in achievable and measurable results and on realizing clearly defined targets. Everything and everybody is held accountable for results. All planning should be ‘SMART’ – specific, measurable, agreed, results-oriented and time-bound. As a result, there is a very limited space for participation, innovation and coping with uncertainties. In government policy practice, plan testing with an overestimation of accountancy and justification dominates at the cost of good plan making. In the Gorcum case, the water board can show results even if the phosphate content of surface water is reached by rinsing, thus by shifting problems to other areas. In the Schalkwijk case, building a ring road, to replace the busy central road, would reduce the number of people living within a short distance from the road. And this is exactly one of the important indicators for results presently used in Dutch planning practice. Figure 4a demonstrates how, in the management approach, the planning process moves to formulate targets as a starting point. Plan making follows the targets and thus focuses on the way and the instruments to reach these targets. The central role of plan testing embodies the focus on accountancy and justification, often called transparency. Efficiency is the leading criterion. The carrying structures approach, represented in figure 4b, follows a step-by-step course that is comes close to the well-known tradition of strategic and operational planning (Faludi,1987:118). There is a balance between the strategic stage on the right side, where plan making dominates and the operational stages on the left side, where plan realising is the leading activity. The role of plan testing is not only important for the parameters of the parts but even more for the evaluation of the planning answers to uncertainty and complexity. Most important are the ex post evaluations after the realisation of the plan, in the stage of use and maintenance. That is the stage where we can learn about the usefulness of the plan. Guiding principles and guiding models primarily play a role in the process of plan making that leads first to a structure plan, a vision about the coherence and synergy of the activities in the future. The vision of framing and flexibility leads to a plan for the role and the nature of carrying structures. On the operational plan realising side efficiency is the principal criterion, but on the plan making side fit is the criterion. The question is whether the plan fits to the local landscape, the local actors and the planning situation. The management approach addresses complexity by assuming certainty in a process of trial and error. The business plan formulates sharp targets as if there was absolute 9 certainty about goals and means. If the underlying assumptions turn out to be wrong the business plan is adjusted. In the extreme case the company goes bankrupt. End results initiative PLAN REALISING PLAN TESTING efficiency (PLAN MAKING) Targets Fig. 4a A management model of planning processes Adaptive planning EVALUATION ex post PLAN REALISING initiative efficiency fit PLAN MAKING Guiding Models Carrying Sructures EVALUATION ex ante Guiding Principles vision structure plan Fig. 4b A carrying-structures model of planning processes. The carrying structures approach is based on the view that public policies and spatial planning cannot risk bankruptcy and cannot radically adjust their business plans after one year. In spatial and environmental planning, with its role in creating long-term conditions an approach of guiding models for carrying structures and adaptive planning is more appropriate. Learning and adaptation are the key issues in dealing with complexity. 10 a systems’ perspective The two cases may also throw light on complexity issues in planning practice from a systems’ perspective. This relates both to the actor networks, their communicative “systems”, and to the physical systems involved. The actors in the Gorcum case, the developers, the water-board technicians and the Water-Line officials, represent groups of actors, usually called “sectors”, operating in different “systems” with different discourses. As mentioned briefly already, in the political and economic systems of the developers, stories with convincing arguments count. The water-board technicians represent the system of technical discourse. They have to convince their colleagues with hard figures, calculations. The socio-cultural systems of the Water-Line officials follow a discourse in which convincing images play a major role. It is with the stories, the calculations and the images the participants in the meetings of the planning process have to convince their boards, councils and colleagues when they come back to their offices. If they fail to convince, their personal position is at stake, within the organisation. If the sector fails to convince their supporting interest groups, the position of the sector is at stake. The case illustrates how the communicative rationality asks for a way to generate discourse coalitions (Hajer, 1995) that can combine the political, the economic, the technical and the socio-cultural perspectives. This is what the carrying structures approach with the guiding models seeks to achieve. The Schalkwijk case, as discussed here, illustrates the physical system. In this case, the two networks’ strategy is the guiding model for the carrying structure of urban redevelopment. In traditional master planning, the end result of the system is defined in a spatial plan. Different sectors, such as the water, traffic and environmental departments have also defined their end results in terms of standards. They pose limiting conditions to the plan. Spatial planners often describe them in the first chapter of the planning document under the title “limitations”. Also natural and cultural heritage usually falls into this category. The two networks’ strategy is not an approach of limiting conditions but of carrying conditions, starting on the other side, the side of the basic potentialities of the ground layer of the urban landscape and the available strategies for robust technical approaches to traffic and water systems. Figure 5 represents the layers of the carrying structures approach. The triangles part goes back to one of the schemes of the Strategic Choice Approach, an influential school of thought and practice in planning theory (Friend & Hickling, 1987). The message is that communication at the level of positions is extremely difficult because there often is no common ground. In negotiations there is a better chance to approach each other if the discussion moves to the layer of interests. There is at least a common point. This is a weak base, however. To reach an agreement the actors should move to the deeper layer of needs. The Gorcum case illustrates how this moving to a deeper layer can work. Both the Gorcum and Schalkwijk cases also demonstrate how the layer of needs should be combined with the carrying structure of technological options and landscape potentialities. The layer approach in spatial planning (CEC, 1999) stresses the importance of the ground layer of the underlying landscape and the network layer as basic conditions for occupation and land-use decisions. Figure 5 combines the layer approach with the Strategic Choice. The scheme illustrates how the carrying structures should be rooted in the potential of the local landscape, combined with a robust frame of eco-technical networks as a basis for long-term needs that are less dependent on the uncertainties of changing interests and positions. Thus these structures can also carry 11 communication processes, demonstrating how inseparable the communicative and technical rationality are. Positions Interests Needs Technical options Landscape potentialities Carrying structures for basic needs sustainable development Fig 5. Layers of communication and planning (after Hickling). In practice this approach will meet with strong counter forces. Greatly encouraged by competing media and politicians, the sectors are being pushed to higher levels instead of deeper layers. They have to show results and position themselves as successful agencies. In this atmosphere of competition, loosing your face compared to other sectors is the worst thing that can happen, especially if it is made clearly visible to the general public. Division of labour is a key to successful management of complex matters. But the division of tasks in sector departments of public administration increasingly also creates barriers. The carrying structure approach explores ways to cooperate on the basic frame for the basic needs. 5. Conclusions How do these two specific cases and the remarks about processes and systems relate to more general literature about planning and complexity? Communicative rationality in planning is a concept inspired by Habermas’ Theorie des Kommunikativen Handelns (Habermas, 1981). The basic idea is the interaction between subjects in a non-hierarchical situation, seeking shared understanding about the situation and agreement to coordinate their plans. It is an action-oriented concept that contrasts with teleological rationality (goals and means), normative rationality (group conformance to common values) and dramaturgical rationality (presentation to an audience, strategic action). This paper started with the polarity between communicative and technical rationality. Technical, as we discuss it here, indeed starts with teleological goals and means reasoning, but the emergence of complexity theory with its emphasis 12 on chaos and adaptive planning may widen the scope. The approach illustrated by the two cases, a guiding model – carrying structure approach, can be described as both technical and communicative. It is technical in the sense of rational reasoning of creating robust conditions, but the approach is not teleological, not goals and means reasoning. It is also communicative in the sense that it has the potential to create a common base, even for actors that follow normative or dramaturgical rationalities. The guiding models are instruments that may be useful to create agreement about conditions at a deeper layer of potentialities and needs in an early stage of the planning process. Evidently, this does not mean that reaching an agreement is guaranteed. It may be rightly argued that the cases discussed here do not demonstrate deep cutting conflicts. This does not mean, however, that the guiding models approach may not be able to contribute to communication strategies in conflict situations. Even then, it remains essential to relate possible solutions or compromises to the deeper layers indicated in Figure 5. In the 1990s, communicative rationality emerged as a dominant feature in the collaborative approach advocated by Healy and others. This approach can be seen as a reaction to the modernist blueprint planning tradition. Healy (1998:1544) for example, focuses on “fostering the institutional capacity to shape the ongoing flow of ‘place making’ activities.” This relates communicative rationality to the physical world, but to places rather than to carrying structures. It addresses the infill rather than the frame. She criticises the economic bias of utility-maximising agency in favour of “ a social being, constructing and reconstructing identity and preferences in different social situations.” (Healy, 1998:1543). No doubt, institutional capacity can be a social carrying condition. But this approach does not address the physical carrying structure and its ecological and technical nature that creates the durable frame for flexible ‘place making’ that concerns us in this paper. Simplification seems to be the only way to address complex matters. Sometimes, in modelling or problem solving, information that cannot be used is simply left out. This reductionism has been successful in taking us to a modern technology dominated world. But the technical rationality of reductionism also failed to solve many problems and has generated new social, environmental and economic dilemmas. An increasing distrust of objective truth and progress was feeding post modernism. The idea that the world around us is just a social construct brought some to extreme relativism. But also within the modernist tradition, researchers, planners and philosophers reacted to the untenable claim of blueprints and linear goals and means reasoning. The Habermasian approach of ‘shared understanding’ is one example. In environmental policy studies the idea of Ecological Modernisation emerged (Hajer, 1995; Spaargaren et al. 2000), seeking to find a way between modernist objectivism and post-modernist subjectivism. This is not only “in between” technical control and undirected interaction. Ecological Modernisation is based on the idea of partnership with nature. Not only humans and nature have intrinsic values, but also “working with nature” has a value in its own right. Guiding models for deeper layer carrying structures can be considered tools for working with nature. These tools are not conceived for realising end results but for creating conditions. Thus the guiding model - carrying structure approach is not only about “being” or “becoming” but primarily about “doing”: creating conditions and interaction between human actors and the physical environment, even if the end results are unknown. In planning, a valuable contribution comes from the Strategic Choice approach (Friend & Hickling, 1987) that is the source of the human interaction part of figure 5. Closer to the technical rationality, systems research developed a better understanding of complexity 13 and uncertainty. One of the pioneers in this context is Checkland who developed the Soft Systems Methodology (Checkland, 1999). This approach focuses on organisations and the basic uncertainties of different goals of different actors in organisations. But in the work of Van Eijk (2003), he applies Checkland’s concepts to urban restructuring and the use of guiding models for carrying structures. Summarising: the guiding model – carrying structures approach we propose in this paper addresses the issue of complexity in two ways. First the carrying structures create a frame of robust conditions that serves as a basis for adaptive planning. Secondly, the guiding models provide the conceptual basis for a process of learning-by- doing. Learning, here, refers both to the learning process of improving the frames, the carrying structures and the process of ‘place making’ that can follow the construction of carrying structures. The examples of the carrying networks of water and traffic have shown that in urban planning practice these are promising carriers. But it is possible that other physical networks as those for energy will be able to play a similar role in specific planning situations. In this paper we focused on physical structures, but it is attractive to include in the carrying structures the institutional capacity for a learning-by-doing practice of adaptive planning. The guiding models are part of an open toolkit. Evaluation studies may improve and add the tools and in a given planning process the tool that fits can be used. Between the extremes of all-control systems and free-floating communication our approach combines creating conditions and a process of learning. Literature CEC, Commission of the European Communities, 1999: European Spatial Development Perspective: towards balanced and sustainable development of the territory of the EU. Luxembourg: Office for the Official Publications of the European Communities. Checkland, P. 1999: Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Wiley, Chichester. Eijk, P. van 2003: Vernieuwen met water; een participatieve strategie voor de gebouwde omgeving.[Renewal with Water, a participative strategy for the urban environment.] Eburon, Delft. Faludi, A. 1967; A decision-centered view of environmental planning. Pergamon Press, Oxford. Friend and Hickling 1987: Planning under pressure: the strategic choice approach. Pergamon Press Oxford. Garreau, J. Edge City: Life on the New Frontier. Doubleday, New York. Hajer, M 1995: The Politics of Environmental Discourse, ecological modernization and the policy process. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Hajer, M & W Zonneveld 2000: Spatial Planning in the Network Society, rethinking the principles of planning in The Netherlands. European Planning Studies 3:3:337-355. Hood, C. 1991, A Public Management for All Seasons? Public Administration 69:3-19. Mastop, J.M. & A. Faludi 1993: Doorwerking van strategisch beleid. [Performance of strategic policy] Beleidswetenschap 1:71-90 Müller, D., S.P. Tjallingii & K.J. Canters 2005: A Transdisciplinary Learning Aproach to Foster Convergence of Design, Science and Deliberation in Urban and Regional Planning. Systems Research and Behavioural Science 22 193-208. Roo, G de 2007: The Question is Being or Becoming! Confronting Complexity with Contemporary Planning Theory. Paper, AESOP Annual Conference, Liverpool. Spaargaren, G. A.P.J.Mol & F Buttel (ed.) 2000: Environment and Global Modernity. SAGE, London. Tjallingii, S.P. 1996: Ecological Conditions. Diss. TU Delft. 14 Tjallingii, S.P. 2005: Carrying Structures: Urban Development Guided by Water and Traffic Networks. In: Hulsbergen, E.D., LT. Klaasen & L Kriens (eds.) Shifting Sense, looking back to the future in spatial planning. (Amsterdam) Techne Press p. 355-368 Tjallingii, SP. 2007: The water issues in the existing city. Chapter 4 in: F.Hooimeijer & W vander Toorn Vrijthoff (ed.) More urban Water: Design and management of Dutch Water Cities. Taylor & Francis, London.p.83-99. Ven, FHM van de & SP Tjallingii (ed.) 2005: Water in drievoud [Water in three ways] Eburon publishers, Delft. Ven, FHM van de, S.P. Tjallingii, P.J.A. Baan, P.J. van Eijk & M. Rijsberman 2006: Improving Urban Water Management Planning. Proceedings of the Water Conference, Tokyo, Sept. 2006. Werquin, A., B.Duhem, et al., Eds. (2005) Green structure and urban planning. (Luxemburg) Final Report of COST action Cll. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. 15