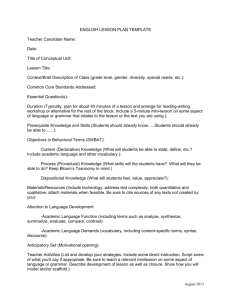

TOPICS - Universitatea din Craiova

advertisement