“Labor Law Reform, Social Dialogue and Union Power in

advertisement

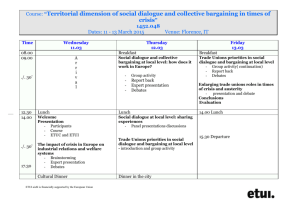

Work Matters: 28 Annual International Labour Process Conference Rutgers University, March 15-17, 2010 th SPECIAL INTEREST STREAM: Are bad jobs inevitable? “The Future of Good Jobs and the Crisis of their Representations in France” Donna Kesselman Université Paris Est Créteil The article studies emerging and diverging labor and employment market representations in France and their implications for defending good jobs. Case studies focus on two 2008 landmark industrial relations laws which overhauled: the common law employment relationship, rules for representative union recognition, collective bargaining. The nature of the laws is analysed through the prism of the process adopted to elaborate them, social dialogue, promoted by the European Union but taking a particular form in president Sarkozy’s France. Key words: labor, social dialogue, employment relationship, France, European Union, trade unions ** * *** * *** * ** Good jobs are a representation of employment relations in a given national labor market. Difficulties in preserving such jobs, or creating new ones, are reflected in their increasingly diverging representations. The link is striking in France whose strictly regulated employment relationship was rooted in widespread consensus. The growing presence of bad jobs corresponds to withering consensus. We propose to look at these various representations and their implications for defending good jobs in France. For representations coincide with work and labor market strategies promoted by social players, be they labor, management or the state. Case studies look at recent evolutions in the legal regime: the revision of the Labor Code, including the common law employment relationship, of representative union recognition criteria and collective bargaining. The battle of representations was a driving 1 force in elaborating this new labor law era through social dialogue, promoted by the European Union but taking a particular form in Nicolas Sarkozy’s France. During the first year of his presidency, high-profile social summits gathered the social partners – the social dialogue term for labor and management – to engage in top-down consensus-seeking, to be distinguished from balance-of-power based collective bargaining. While agreeing that traditional employment relations have been destabilized, strategic responses differed as to how to best represent workers. A continuum extended from propping up the employment relationship to doing away with it all together – i.e., negotiating transitions towards a flexicurity model, which transfers protections from the subordinate employee job status to the worker as individual. The result has been a fragmented legal representation which formally integrates these various concerns but whose reality will necessarily play out in the confrontation of social forces. Sarkozy is no Thatcher: the iron woman never received the unions to negotiate or dialogue, but rather gave herself the mandate to break their backs (Jeffrys 2009). For her younger neo-liberal co-thinker, as presidential candidate in France, a main campaign theme was for professional organizations, both labor and employers, to be take more responsibility in public affairs (Bévort 2008): “I will strongly support social dialogue… This implies thoroughly modernizing it. I hope the next five years1 will be those of revitalizing social democracy which is not lost time, but may be gained time if everyone plays the game. ….” (Sarkozy 2007). One year later, high-profile social summits had produced all but unanimous accords later transposed into statute laws which overhauled industrial relations in France. According to then president Sarkozy on April 19, 2008: “The complete refoundation of social democracy is on the agenda… The social dialogue between social partners has been a success.” (Le Monde). What could the right-wing president’s satisfaction mean for working people and labor organizations in France? Before examining the two 2008 labor laws, a look at social dialogue as paradigm in the European Employment Strategy provides the framework for industrial relations transformations in France. Finally, what may be deemed a “crisis” of work and labor market representations is indicative of underlying social and political tensions and trends. 1 The five year presidential mandate in France. 2 I. European Social Dialogue: A Story of “Rigidities” Social Dialogue is perceived as a new and potentially transformative paradigm. The lose International Labor Organizations definition includes: “…all types of negotiation, consultation or simply exchange of information between, or among, representatives of governments, employers and workers, on issues of common interest relating to economic and social policy. …. The concept of social dialogue and its definition vary from one country to another and from one region to another and continue to evolve.” (ILO A, emphasis ours) The common characteristic is joint labor and management consideration of economic and social policy issues. Its European Union representation has taken various forms. The EU Treaty mandates the European Commission to use social dialogue to achieve “better governance of the enlarged Union and as a driving force for economic and social reform”. (Europa A). It thus promotes national and decentralized territorial experimentations, when they serve to implement EU policies. (Jobert 2008) Pan-European social partner encounters have hammered out minimalist but principled framework agreements (Articles 138 & 139 EC), some transposed through binding directives into national law. These include: paternal leave, part-time work, fixed-term work. At another level, EU institutions have facilitated autonomous agreements of Europeanizing corporations and their transnational employee works councils. A more controversial area of social dialogue concerns employment policy, consolidated in the year 2000 Lisbon Strategy for Growth and Jobs. The lofty goal to “make Europe, by 2010, the most competitive and the most dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world” was to be achieved through an Open Method of Coordination (OMC), adopted to existing mechanisms such as the European Employment Strategy (EES), also called the Luxembourg process. (Europa B) The OMC formulates the “best” labor market practices in terms of benchmark2 objectives to incite member-states to follow suit. It is a somewhat watered down version of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty’s monetary union convergence scheme which sets strict command and control-type macroeconomic standards in member countries, such as its Stability Pact’s 3% annual budget deficit ceiling. The European Employment Strategy is thus a less top-down regulatory system of governance, approaching labor market goals through participatory policy-making by social partners. Albeit unsanctioned, the EES remains strictly coordinated, 2 The English term “benchmark is used as such. 3 seeking convergence or partial convergence though specific policies are shaped by national member-states. (Abbott, Snidal 2000) Each year social dialogue engages many levels of government, social partners and other actors to produce National Action Plans. Progress is closely monitored by EU institutions and new targets set (Trubek, Mosher 2001) The EEC ambitioned to usher in “a profound modernization of Europe's economy and social system for the 21st century… to meet the challenge of insufficient growth and intolerable unemployment”. Structural reforms would reduce unemployment by increasing labor market participation rates to 70% overall and 60% for women by 2010. Benchmarks promoted: more women working, unemployment activation and less early retirement; more part-time employment and, while encouraging skilled jobs, “fewer obstacles to low skill work” by adjusting tax systems. (Luxembourg Summit 1997) This EES’s representation of growth therefore implies more “bad jobs” – if defined as a deconstruction of open-ended, full benefit, long-term employment. It is essentially a supply-side strategy designed to alter macro-economic policies that create impediments to employment. (Trubek, Mosher 2001, 810) The Lisbon Strategy, relaunched in 2005 (Kok Report), is described as the convergence of two driving forces of the EU’s evolution: one to preserve a European social state; the other to strengthen participatory EU governance. (Natali, Porte). The two combined provide a working definition of today’s social dialogue: the tool of governance aimed at renewing a 21st century European Social Model by reforming it. The soft law approach is meant to accommodate EU macro-economic structural reforms (Europa C), with contradictory pressures to sustain national welfare state represenations and gains. Lisbon stimulated public debate over how the EES would affect the 21st century European Social Model (Husson 2008). The need for a changed representation, a “new development model”, originated in then European Commission president Jacques Delors’s 1993 White Paper on Growth, Competitiveness and Employment. It diagnosed labor and job market regulations as rigidities, the root cause of endemic, continental-wide unemployment and Europe’s lack of market dynamism, also known as Euroscleros. The EU thus incorporated the OECD’s pro-flexibility paradigm, modeled after American employment-atwill. In its dogged quest for national models (Esping-Anderson 2007), Europe’s most promising prospect to conciliate its ideals of economic efficiency and social solidarity since the welfare state has been “flexicurity”, the trendy doctrine which took policy-makers and academics by storm. Flexibility for firms, and security for workers, are not only not 4 contradictory, but mutually supportive, through the intermediary of social dialogue. It is most accomplished in the “Danish triangle” combination of easy hiring and firing (flexibility), high benefits for the non-employed (security), labor market activation policies in training and job placement. Job security – and unemployment – are replaced by revenue security, thus avoiding the displacement of risk towards the actors themselves like in Anglo-Saxon style Workfare. (Boyer 2006) The 10 year balance sheet of Lisbon is currently subject to debate but consensus exists over its failed ambitions, even before the recent crisis. France’s employment rate, while increasing 2 points from 2000 to 65,1% in 2008 still remained low compared to other OECD countries and is especially unequal due to low rates for the under 25 and over 54 year age groups. (INSEE 2009) As for structural rigidities, even the OECD has questioned the causality between labor market flexibility and job creation. (OCDE 2004, in Ramaux, 2006, p 84). In France, for instance, unemployment rates were hardly impacted from deregulation measures in the mid-1980s, such as the elimination public authorization for layoffs (Kesselman, 2009 JIST) The Lisbon process and EES has nevertheless been acknowledged for creating an environment for coordinated structural reform in national labor markets over time (European Union 2000; Doutriaux, Lequesne, 2008). And international financial institutions persist in promoting the flexibility paradigm. A joint OECD-French government conference held in 2006 urged France to remove obstacles to manpower demand, to adapt remunerations and labor costs to market evolutions and thereby contribute to economic dynamism. It evoked the “indispensable” need of reevaluating its national “conception” – one might say representation – of social protection legislation. (Cotis, Martin, DARES-OCDE 2006). So goes for flexibility. And what about security? In his conference contribution devoted to “Flexibility and Securization of Professional Career Paths”, Jacques Freyssinet commented on the prophetic promises of flexicurity. It is one of a series of vague concepts (concepts flous) that play a role in socio-economic debate. Their ambiguities are precisely what allow actors having different, even antagonistic objectives and analyses to adopt them as a common framework of negotiation. (Freysinnet 2006). This is the context of social dialogue in France. Determination on the part of labor market flexibility proponents alongside broad and blurred references to workers well-being. Social dialogue’s main quality is its inclusiveness of such vastly different work and labor market representations. The enormous and complex institutions through which the European Employment Strategy and member states interact, mobilizing actors and resources galore, all 5 come down to one question: how to represent and create more good jobs in the 21st century globalizing marketplace (Azaïs 2010). In the highly regulated French labor and employment markets such has been the long, and often rocky road, of social dialogue. II. Social Dialogue in Sarkozy’s France What did one key year of social dialogue mean for industrial relations in France? Two landmark laws embodied the French government’s institutionalization of social dialogue, whereby any bills dealing with work, employment or labor relations must be submitted by government for previous negotiation to national social partners (Modernization of Social Dialogue Law3), even at the expense of waning parliamentary prerogatives. (Teyssié 2009) The new 2008 French Labor Code4, symbolically announced on May 1 Labor Day, was based upon a previously elaborated social dialogue accord. By introducing new rules on union recognition and collective bargaining, the 20 August5 law’s first ambition was the “renovation of social democracy”. The same could also be said about the way the law came about: the transposition into statute law of the high-profile April 9 social dialogue accord referred to as the Common Position (Position commune). II.1. A New Labor Code: Flexicurity à la française? Revising the French Labor Code through social dialogue occurred under the name of government proclaimed “labor market modernization”. After months of bi-lateral social partner dialogue the 11 January 2008 agreement was signed by all management social partners and four of the five nationally recognized labor confederations. Was it a step towards flexicurity à la française? Its answer to this question reflects each organization’s own representation of good jobs. During negotiations, a continuum extended from the preservation and strengthening of the existing common law employment relationship to doing away with it through flexicurity transitions which transfer protections from the job market to the worker as individual, whatever direction her career path may take, including disconnections. In its Article 1 the 2008 Labor Code reasserts the open-ended contract with full benefits – contrat à durée determine (CDI) – as the “general and normal form of the employment “Loi n° 2007-130 du 31 janvier 2007 de modernisation du dialogue social” La loi n° 2008-596 du 25 juin 2008 « portant modernisation du marché du travail », publiée au JO du 26 juin 2008. La nouvelle loi reprend les principales dispositions de l’Accord national interprofessionnel (ANI) du 11 janvier 2008 signé par les organisations syndicales et patronales représentatives, à l’exception de la CGT.. 5 Loi n° 2008-789 du 20 août 2008. 3 4 6 contract in France” as well as the short-term (contrat à durée determine, CDD) and temporary (interim) work contracts as “the contractual alternatives to adapt to momentary manpower needs”. The reassertion did represent a setback for the government’s original intent to introduce a single contract (contrat unique, MEDEF 2004): one legal framework, modeled after U.S. style employment at will, to replace the numerous legally defined contract configurations; the three mentioned above and dozens of activation contractss The youth first job contracts were slated as a first step towards such flexibility, as employers could layoff under 26-year-olds without any motive or previous notice. However their forced withdrawal – one for large firms (contrat première embauche (CPE) ) under pressure of popular mass demonstrations in spring 2006 and the other for small firms (contrat nouvelle embauche (CNE) by international law, upon French union appeal to the ILO – was interpreted by some, including FO, as public support for the open-ended, full benefit CDI. Given its reading of the draft law as reinforcing the traditional employment relationship, the necessary means to defending good jobs, considering that it was not a step towards flexicurity, the Force Ouvrière (FO) confederation signed. (FO 2008) Au contraire, stated the CFDT confederation which also signed, but precisely because the labor code did mark, from its perspective a step towards flexicurity à la française. France’s flexicurity enthusiast touted the portability of complementary health-care benefits and training rights earned through seniority from one employer to, in case of layoff, a future employer, even if the degree of portability did not meet expectations and other proposals to secure professional career paths beyond the employment relationship were not incorporated. It While modest, this was a step in the right direction, for the gist of CFDT brand flexicurity is the ability to manage the inevitable nobilities, chosen or not, given the changing nature of work (CFDT 2006). The new accord was “an important advancement of social relations in France introducing new dynamics”. (CFDT 11 January 2008) The powerful MEDEF employers’ association signed and gave its blessings to what it also deemed “historical… new era for social relations and the economy in France: it invents French flexicurity”. Contrary to FO’s reading, had succeeded in “moving the frontiers (fait bouger des lignes)” of the employment relationship “which hadn’t been moved dozens of years”. (MEDEF 2008) It welcomed measures perceived as easing rigid legal layoff procedures such as the no-fault system of separation by mutual consent (concept of séparabilité) and the new “missions contract”. This non renewable CDD contract of 18 to 36 month duration is tailored to managers and engineers hired to carry out a clearly defined mission. It is nevertheless more strictly regulated than the initial version whereby realization 7 of the mission was sufficient to justify termination. (Virville 2004, MEDEF 2004). For the MEDEF, significant steps were made towards labor market flexibility, i.e. good jobs for employers. Only the CGT refused to sign. The recalcitrant majority labor federation agreed with this management flexibility analysis but denounced the deregulation of layoffs and missions contract as more precariousness. (CGT 2008) The CGT’s position on flexicurity is complex. In parallel to the CFDT it developed its own version called Professional Social Security (Sécurité Sociale Professionnelle) which advocated a system of universal workers rights linked to a new status for all workers, along the lines of social security healthcare (Grimault 2008). The confederation, however, is quite adept at its juggling act of presenting various flexicurity representation on the public it addresses. So while taken a radical anti-management stance when criticizing the January 2008 social dialogue accord, that it has helped to shape over previous months, its press statement also pointed out that the accord did not go far enough in gaining new guarantees to establish “transferable rights throughout one’s career and constitute professional social security”. (CGT 29 January 2008) The result is a fragmented legal representation which formally integrates these diverging and oft contradictory labor and employment market conceptions. They are witness to tensions which undermine what was formally a consensus around the employment relationship in France. A shakeout will among complex social and political forces, for securing and preserving good jobs, we necessarily occur through confrontations know, all comes down to waging a good fight. This is the link with the second major 2008 law which overhauled the collective bargaining regime in France. New emphasis is given to the local workplace, as opposed to professional sector-wide, called branch collective bargaining agreements (conventions collectives). Representations of the future of labor, as portrayed in social dialogue, impacted this legal regime in a context of declining workplace balance of power. II.2 A new representation of representative unions The 20 August 2008 law on representative union recognition and collective bargaining was heralded by president Sarkozy as the most important reform since the Liberation. (18 April 2008). It was widely acknowledged that existing criteria, set out in 1945 and decreed in 1966, needed updating. The labor landscape now includes such inter-professional 8 organizations as the UNSA and SUD, or professional sector federations such as the FSU in education. Sarkozy’s remark symbolically recalled the Liberation criterion for a labor organization’s “patriotic attitude during the [World War II] occupation” 6. But eliminating reference to the mythical French resistance movement marked as well his clear break with its program whose welfare state laid the basis of postwar social and political consensus: the first democratically elected government under hero Charles de Gaulle included the resistance movement’s broad spectrum, with Socialist Party and Communist Party ministers. As France’s first post-, postwar generation leader, Sarkozy hailed the new era of industrial relations and his satisfaction at renovating social and political consensus through social dialogue. Even more so than for its recent predecessor, the Labor Code, the April 9 Common Position pact which pre-negotiated the 20 August Law – endorsed by the main employer associations and the two biggest labor confederations, CFDT and this time the CGT – became social dialogue’s signature trademark. Gone was the previous system of national recognition by statute law, whereby the “Big 5” – CGT, CFDT, CGT-FO, CFTC, CFE-CGC7, who had met the national criteria in 1966 – were deemed automatically representative at all levels in collective bargaining and designating workers’ delegates. Recognition will no longer be determined top-down but bottom-up, depending on a union’s electoral scores8. This is a radical transformation in French labor history and culture: the system of election-based representation had been rejected since the early 20th century in the name of unions representing not only their members, but of the entire profession (Bévort, Jobert 2008). Unions represent popular interest in social institutions concerning public housing, welfare benefits, in labor courts. Only two of the “Big 5” unions signed the April 9 Common Position. Smaller confederations feared that electoral recognition thresholds fixed at 10% locally and 8% at branch and national levels would depreciate their influence or eliminate them altogether. The statute was also condemned by upcoming unions which had counted on reform to more Other criteria were: number members, of paid dues, the organization’s experience and seniority of the organization. 6 7 The CFTC (Confédération française des travailleurs chrétiens) was the organization remaining after the majority CFDT split in 1964, intending to weaken the links with Christian unionism. The CFE-CGC represents in particular the category of cadres, loosely translated by supervisory personnel at all levels who enjoy union rights in France. 8 The 20 August 2008 law sets out seven criteria: respect of Republican values, independence, financial transparancy, minimum two years seniority in the professional and geographical negotiating area, electoral criteria. 9 equitably reflect their presence. In its statement denouncing the Common Position, UNSA claimed: “This semblance of democracy has no other aim than the restructure (recomposer) the trade union landscape around the CFDT and the CGT. The new criteria will ultimately shift the balance of workplace power. And a restructured, bi-partite union landscape divvied up between the two biggest confederations is generally considered to be the most likely scenario. The CFDT, with 21.81% during the 2008 national labor court elections is slated to comprise the reformist wing and the CGT, at 34%, the more class confrontational wing. CGT general secretary Bernard Thibault concurs with this depiction, believing that it would help de strengthen labor because in France there are “too many unions and not enough union members”. (11 May 2008) Initial fusion talks between such moderate organizations as UNSA and the CFE-CGC have since collapsed, others are engaged. At its February 2010 convention the FSU education federation extended a hand to CGT and SUD leaders who addressed delegates. The FO confederation is situated somewhere in the middle: with its 15.81% in national labor court elections, it hopes to remain representative at national and branch scales, but its uneven presence among professional sectors is reason for concern. It was the big loser (with the CGC and the CFDT) in the first major electoral showdowns when losing its representative status in the SNCF national railways, edged out by the upcoming SUD-Rail union, portrayed as a more radical alternative to the CGT. The topography of labor representation in France could end up, however, looking quite differently from this hypothesis of bi-polar “hegemonic stability”. First of all, it clouds over internal tensions within Common Position co-signing organizations, notably the CGT. A number of rank-and-file unionists, on a principled basis and/or fearing for their own existence in smaller professional CGT unions, have contested the confederation’s endorsement of the Common Position, alongside the ultra-moderate CFDT and the employer associations, as noted in resolutions and proposed amendments at the 49th CGT Convention in Decmeber 2009 (in author’s possession). Legal scholar Françoise Favennec-Héry predicts, in lieu of renovating social democracy, overpowering trends towards decentralization and instability more likely to undermine its foundations. (Favennec-Héry June 2009) Decentralization would result from local union recognition: disparities in representation from one workplace to another and even within firms. Workers in small and mid-sized firms, where elections are less frequent, would be all the more vulnerable if unable to call upon national representatives to intervene. Representation would also tend to be unstable, for varying between electoral 10 cycles: a union may be recognized in one election then disqualified in the next, thereby excluded from union rights while awaiting new elections four years later. The replacement of presumed recognition by local electoral results is but the “technical expression” of a new conception of representative unionism with regards to is primary mission, collective bargaining. (Favennec-Héry March 2009, 639). Common Position negotiators were surprised to discover in the 20 August law, alongside the representative union recognition criteria, a workplace bargaining procedure which had not been previously submitted to consideration of the social partners. The issue of work time entered the sphere of local collective bargaining. Thus the full title of the law: on renovating social democracy and reforming work time. 9. No increase or reduction of work time was legislated; the legal 35hour annualized weekly average remains the norm. But local opt-outs (work week, overtime pay, reduction of comp-time days for white collar employees) can be negotiated between employers and representative organizations, as newly defined. The common law source for work-time henceforth becomes the local agreement, bargained directly by firm level social partners. Even provisions for individual employeremployee contracting are included. This may be the law’s most controversial provision. It denotes a major departure from traditional French labor relations which have privileged national, branch-wide collective bargaining accords. It reverses the “hierarchy of norms” (principle of favor) handed down from the 1930s Popular Front, which was specifically designed to prevent any firm-level exemptions from industrial-wide agreements or statute law when they are less favorable to workers. For some in the Parliamentary opposition and labor unions this reversal would create an ominous precedent, jeopardizing national statute law and branch collective bargaining agreements which have been the historical vehicles for social betterment. It breaches the social foundations of the Republic and has been dubbed the Trojan Horse of the Anglo-Saxon bargaining model. (Mélenchon 2008) In less lyrical fashion but acknowledging and advocating the same trend, the review Conseil d’Analyse Economique calls for a new model (refondation) of social law to better conciliate objectives of social protection and economic efficiency, which necessarily implies a reduction of regulatory law in favor of contract law and local bargaining. (2010) In sum, what is in jeopardy is the vertically unifying voice which leant legitimacy to contestation at all levels and workplace labor pluralism: as unequal it may have been in reality, it has existed in the collective consciousness and confidence of workers in France. 9 “La loi portant rénovation de la démocratie sociale et réforme du temps de travail” 11 Labor’s essential role at the branch level will inevitably be challenged. And yet automatic recognition of national unions to negotiate in all professional branch collective bargaining agreements – 99% of employees and almost all employers are covered – is a key to understanding the often cited paradox of sustained labor influence in a country which counts lower union-member density than even the United States. The fragmentation of labor representation resulting from election-based recognition runs the risk of diminishing labor’s representation a potent independent player in French politics. Conclusion: Social Dialogue and the Crisis of Representations Social dialogue has been posited as a potentially transformative paradigm. This is the least that can be said of 2008 social dialogue summits in Sarkozy’s France, a landmark year for industrial relations transformations: the common law employment relationship, representative union recognition and collective bargaining. At least as important was the procedure adopted to elaborate these transformations. The resulting legal fragmentation may be deemed a “crisis” of work and labor market representations which largely reflect a withering consensus and growing tensions around what goods jobs are and how to defend them. Resolving this dilemma may be asking too much of social dialogue. Certainly, the protracted debate over how they differ (Mias 2009) is in itself evidence that social dialogue, a notion which is deliberately imprecise, adaptable and evolving, is not equivalent to balance of power-based collective bargaining. Its goal, recalls the ILO, is to “…promote consensus building and democratic involvement among the main stakeholders in the world of work”. But what is consensus? The social dialogue process – also called social partnership, consultation, coordination – has been termed as neo-corporatism. The liberal democratic model, as opposed to its early 20th century authoritarian predecessors, described cooperative tripartite public policy governance under the aegis of 1970s left-learning governments in northern Europe; this “specific form of social regulation” has since evolved differently in Western European countries (Rehfeldt 2009). A common characteristic is the institutionalized cooperation of labor and management in employment and welfare policy-making (Kesselman, 2003). What has changed is the balance of social power as organized spokesmen of working people find themselves today on the defensive. In France top-down consensus-seeking therefore tends towards lowest common denominators, not the tough compromises hammered out through 12 social and political confrontation, and there is reason de doubt the real degree of consensus they represent. (Rehfeldt 2009) This may seem surprising for France whose social movement has entered the 21st century in rather healthy shape. Almost every year has seen mass movements, from the shop floor to the streets, in opposition to the 2003 retirement reform, first youth contracts, public school educator cutbacks, or higher university and hospital reform in 2009, to name a few. The 2005 groundswell “no-vote” to the European Constitution also merged with anti- reform protest, to the point of forcing into retreat left-wing parties and labor union leaderships who had supported the initiative. But there was no convergence between mass popular movements and social dialogue social summits. At no time did labor leader negotiators call for popular support when fundamental workers interests were on the table. This, certainly would not have been an easy task, given the diverging representations in presence. And while Margaret Thatcher, president Sarkozy is even less so a Scandinavian social democrat. The social partnership he fosters is a Bonapartist brand of social contract. 2008 social summit partner negotiators, especially labor confederations, were solemnly forewarned that if no agreement were reached, his conservative governing majority would proceed to legislate reform without them. In what the president unilaterally dubbed the “Shared Agenda” (agenda partagée), he announced: “On each theme, the social partners have a choice: either seize the subjects and negotiate amongst themselves… or if they prefer, allow government to take its responsibilities.” (Sarkozy, Dec. 2007). Such were the presidential rules imposed on the social dialogue game social partners had been summoned by candidate Sarkozy to play. National social dialogue has continued in France. Since fall 2009, the government has convened social partners and other actors to the Estates-General of Industry (Etats Généraux de l’Industrie), whose stated goal, on the official website, is to “accompany French industry, beyond the current crisis, towards long-lasting markets of growth and employment” through the elaboration of an “economic and social pact”. President Sarkozy has expressed his satisfaction at the labor market modernization which has been produced through social dialogue in France. In his 2010 New Years Greetings he explicitly paid “particular homage to the social partners who have demonstrated a great sense of responsibility”. A new social summit to organize social dialogue around retirement reform, the main issue on this year’s social agenda, has already been called but participating unions have warned that they “will not accept any masquerade of concertation” (AFP). Government objectives bring us right back to the EES benchmark targets: reducing labor costs and increasing the employment rate by extending the legal retirement age. Public finance 13 shortfalls due to the bank bailouts are also a barely hidden agenda. Critics fear that crisissolving social dialogue will be overwhelmed by employer agendas. (Freyssinet 2009) To what extent social dialogue and social movement converge may be the only way to judge to what extent new consensus is being forged in France, around the representation of good jobs as well as kind of labor unions and collective action are capable of defending them. 14 Bibliography Abbott, K.W., Snidal, D. 2000, “Hard and Soft Law in International Governance”, International Organization 54 (3). AFP, 14 February 2010, “Les retraites, réforme central de l’agenda social 2010”. Appay, B., 2006, Il lavoro ‘non standard’ nelle dimensione europea. Il caso francese. Il « nuovo » nel mercato del lavoro, A.N. Lavori, Roma, Sapere, pp. 4857. Azaïs, C. (ed), 2010 (to appear), Employment and work in a globalised world: lessons from the South? When globalisation sheds new light on, Brussels: Peter Lang Publishing. Bévort, A. 2008, “De la position commune sur la représentativité au projet de loi : renouveau et continuité du modèle social français”, Droit Social, n° 7/8, juillet-août, p. 823-833. Bévort, A., Jobert, A, 2008, Sociologie du travail : les relations professionnelles, Paris: Armand Colin. Boyer, R. 2006, La Flexicurité Danoise - Quels Enseignements Pour La France?, Paris : Cepremap. CFDT 11 January 2008 CGT 29 January 2008, “Négociation sur le marché du travail : La CGT ne signe pas l’accord”, Press Release. CGT, 15 January 2008, "Commentaires CGT accord Modernisation marché du travail du 12 janvier 2008”. CGT-FO, 15 January 2008, "Négociation: Marché du Travail”, Circulaire Confédérale. CFDT, July 2006, “Engagés dans une société en mutatation”, General Congress Resolution, Syndicalisme hebdo, no. 3083, p. 62-91. Conseil d’Analyse Economique, 2010, “Refondation du droit social: concilier protection des travailleurs et efficacité économique”, Analyses Economiques n° 1/2010. Cotis, J-P, Martin, J., 16 November 2006, Introduction, “La réévaluation de la stratégie de l’OCDE pour l’emploi: diagnostic, limites et enseignements pour la France”, DARES-OCDE. DARES, 2003, Les politiques de l’emploi et du marché du travail. La Découverte, Paris. DARES, août 2005, Les mouvements de main-d’œuvre au quatrième trimestre 2004. Premières informations et premières synthèses, no 32-2, Paris. DARES-OCDE., 15-17 novembre 2006, La réévaluation de la stratégie de l’OCDE pour l’emploi: diagnostic, limites et enseignements pour la France, colloque. 15 Doutriaux Y., Lequesne, C., 2008, Les institutions de l’Union européenne, Paris : La Documentation française, 7th Edition. Esping-Anderson, G, 2007. Les Trois Mondes de l’Etat-providence. Paris : PUF (2° édition). Etats Généraux de l’Industrie, www.etatsgeneraux.industrie.gouv.fr/ ETUC (European Trade Union Congress). 2001."Luxembourg” Process: ETUC Employment ‘Fiches’." Manuscript. Europa A, “Social Dialogue”, europa.eu/legislation_summaries/employment_and_social_policy/social_dialogue Europa B, “Social Dialogue”, europa.eu/scadplus/glossary/lisbon_strategy_ Europa C, “Growth and Jobs”, http://ec.europa.eu/growthandjobs/index_en.htm European Commission. 1997. An Employment Agenda for the Year 2000: Issues and Policies. www.europa.eu.int/comm/employment_social/summit/en/papers/emploi2.htm. European Commission, 2006, Emploi en Europe 2005. Direction générale emploi et affaires sociales, Bruxelles. European Commission. 2000. Joint Employment Report 2000, Part I. European Commission, 1997, Documents for Luxembourg Employment Summit. Favennec-Héry, F., March 2009, “Le droit de la durée du travail, fin d’une époque", Droit social, no 3. Favennec-Héry, F., June 2009, “La représentativité syndicale” Droit social, no6. Freyssinet, J., 25-27 Novmeber 2009, “Les réponses tripartite àla crise dans les principaux pays d’Europe occidentale” Forum on Social Dialogue and Industrial Relations, BIT. Freyssinet, J., 2006, Travail et emploi en France : état des lieux et perspectives. La Documentation Française, Paris, p. 47. Freyssinet, J,. 2006, “Flexiblité et sécurisation des trajectories professionnelles”, Colloque DARES-OCDE, novembre 2006. Husson, Michel, 2008, Avant-propos, La revue de l’IRES, no° 58, 2008/3. Jefferys, S., 2009, “Working hard to change the French Social Model: Is Sarkozy a French Thatcher?”in Béatrice Appay, Steve Jeffrey’s (ed), Restructurations, précarisation, valeurs, Paris: Rfoyop, Octares Editions. Goetschy, Janine. 1999."The European Employment Strategy: Genesis and Development." European Journal of Industrial Relations. 5(2):117-137. Grimault, S. January 2008, “Sécurisation des parcours professionnelles et flexicurité: analyse comparative des positions syndicales”, Travail et Emploi, no 113. ILO A, “Social Dialogue”, www.ilo.org/public/english/dialogue/themes/sd.htm 16 INSEE, 2009, “Taux d'activité et taux d'emploi depuis http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/tableau.asp?reg_id=0&ref_id=NATnon03168 1975” Jobert, A. (ed) 2008, Les nouveaux cadres du dialogue social: Europe et territories, Brussels: PIE-Peter Lang. Kesselman, D., 2009, “Le travail non standard comme outil comparatiste des frontière de la relation salariale : France et Etats-Unis”, Jounées internationales de la Sociologie du travai (JIST). Kesselman, D., 2003, “Nelson Lichtenstein vs. Nelson Lichtenstein and the 20th Century Labor Question”, Revue Transatlatnica, 1 |2003. Kok, W., 2003, “European Employment Task Force” Kok Report; Commission Européenne. Levy, Jonah. 1999."Vice into Virtue? Progressive Politics and Welfare Reform in Continental Europe." Politics and Society. 27(2): 239-273. MEDEF, Moderniser le Code du Travail. Les 44 propositions du MEDEF. Paris, mars 2004. MEDEF, 11 janvier 2008, communiqué. MEDEF, 11 janvier 2008, "Kathy Copp Interview”, France Inter. Mélenchon, J-L, août 2008, "Sur la Position Commune”, www.jean-luc-melenchon.fr. Mias, A. 2009. "Les registres de l’action syndical européenne”, Sociologie du travail 51. Pisani-Ferry, Jean. 2000. Plein emploi. Paris: La Documentation française. Natali, D., Porte, C., 2009, "La participation dans la stratégie de Lisbonne (et au-delà). Une comparaison des MOC sur la stratégie européenne pour l’emploi et les retraites”, La Revue de l’IRES, Numéro spécial : Stratégie de Lisbonne : échec ou solution pour le futur ?, n°60, 2009/1. Portugal Presidency. 2000."Presidency Conclusions." Lisbon European Council, 23 and 24 March. Ramaux, C., 2006, Emploi : éloge de la stabilité. L’Etat social contre la flexicurité. Mille et Une Nuits, Paris. Rehfeldt, U., November 2009, "La concertation au sommet toujours d'actualité face à la crise?”, Chronique internationale de l’IRES, no 121. Sarkozy, N. 2007, Presidential Program. Supiot, A. (ed.), 1999, Au-delà de l'emploi. Transformations du travail et devenir du droit du travail en Europe. Flammarion, Paris. Teague, P., 2001, "Deliberative Goverance and EU Social Policy", European Journal of Industrial Relations. vol. 7, no. l. Teyssié, B. 2009, “A propos de la rénovation de la démocratie sociale”, Droit Social, n° 6. Trubek, D., Mosher, J., 2001, “New Governance, EU Employment Policy, and the European Social Model”, Jean Monnet Working Paper No. 6/01, Symposium: A Critical Appraisal of 17 the Commission White Paper on Governance, European Union Center, Madison: University of Wisconsin. Virville, M., 2004, Pour un code du travail plus efficace. Rapport au Ministre des affaires sociales, du travail et de la solidarité. Paris : La Documentation Française. s 18