Working Conceptualization of Reflective Practice – Discussion

advertisement

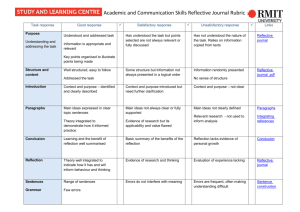

Introduction to “reflective practice” and a working conceptualisation for discussion purposes A work in progress – July 2011 – GAJE workshop Research project: Encouraging reflective practice in a professional school: Developing a conceptual model and sharing promising practices to support law student reflection As a Community Leadership in Justice Fellow, I undertook an action research project at a Canadian law school hoping to encourage the adoption of reflective practice as a core competency for legal professionals. In the pages that follow, I set out some brief background to explain the concept of “reflective practice”. (An Annotated Resource list is contained in the Resource Kit for Reflective Practice and contains references for the literature cited below.) The purpose of the working conceptualisation (which starts on page two) is to reconcile different definitions and to establish a holistic framework for discussion purposes. I’ve set out three key interrelated aspects of a reflective practice model based on what I’ve read in the literature, learned from the eight law professors I formally interviewed, observed while sojourning at the law school for an academic term and at legal education workshops, and from my experience as a poverty law practitioner in a community legal clinic for 26 years. Several of the professors I interviewed recommended a simpler working definition be developed—this is a work-in-progress and the current draft is at the end of this short discussion paper. How do you view “reflective practice”? Do you believe developing a “reflective practitioner” (RP) conceptual model specifically for legal education would be helpful? How can we encourage building reflective capacity and promoting the concept for law students? Can the concept be simplified so it is quickly understood? As a faculty member, would you describe yourself as a reflective practitioner? Do you model reflective practice for your students? How does it or could it help you improve your teaching practice? Context – Reflective practice is an important professional capacity and attribute Faculty in medical and health disciplines, teaching and social work professions have explicitly adopted reflection and reflective practice as essential attributes of professional competence, although the definitions are diverse and often amorphous. The legal profession has also begun to incorporate a notion of reflective practice both in law schools and in legal practice, although we are at an early stage. There is little academic literature promoting reflective practice as a component of legal education in Canada. In a 1993 article about poverty law scholarship, Buchanan stressed that lawyers should be “practising” critical theory, by becoming a “practicing theorist”, an aspect of critical reflection which enriches Schön’s (1983) original notion of reflective practice. Advocating for the encouragement of reflective practice, Macfarlane (1998, 2002, 2008) has described reflective practice as a method to encourage the development of the new legal skills required for mediation and alternative dispute resolution, and to help lawyers cope with the ethical challenges presented by these new ways of practicing law. Rochette and Pue (2001) argue that reflective practice helps meet evolving professional and societal demands which include developing “responsiveness to change, flexibility and professional self-growth,” contrasted with conventional legal education in “black letter legal rules” and doctrinal analysis. In the field of clinical legal education, American educators have encouraged reflective practice, principally through experiential learning opportunities, with reflection most often fostered through learning journals. Sonsteg et al (2007-2008) in A Legal Education Renaissance: A Practical Approach for the 21st Century extol the virtues of reflective teaching and learning. Ogilvy, Wortham and Lerman et al (2007) place a great emphasis on law students learning about reflective lawyering. Schwartz (2008) in his text Expert Learning for 1 Law Students stresses the role of reflection in the self-regulated learning cycle he recommends for students. Similarly, Stuckey et al (2007) endorses the development of a capacity for self-reflection while Neumann (1999) proposes six strategies to incorporate Schön’s concept of reflective practice, including in a first year skills’ course in legal writing. The movement to humanize legal education (Washburn Law Journal, 2008) and the field of therapeutic jurisprudence also discuss the need for building a reflective capacity in law students and thereby contributes to a more holistic model for reflective practice (Silver, 2007). In the United Kingdom over the last decade, law teachers have been augmenting their teaching strategies to develop law students as reflective practitioners with dedicated support from the UK Centre for Legal Education (Hinett, 2002). Julian Webb (2006) uses the term reflective practice to describe how to actualize Arthurs’ (1993) notion of humane professionalism, and there are also favourable references to the concept in his earlier text Teaching Lawyer’s Skills (Webb & Maughan, 1996). Some Australian law schools have identified reflective practice as a desired and expected attribute of law graduates, and at least one law school has proposed strategies to develop reflective capacity in the first year curriculum (McNamara & Field, 2007). That a galvanizing conception for RP is necessary seems self-evident. There is a growing awareness that legal education must be enriched to nurture the kind of legal professionals that our increasingly complex world requires. Professional knowledge is already multi-faceted, and the constant need to learn new skills and keep abreast of substantive law changes is challenging for lawyers. Practitioners require a range of skills, competencies and capacities that continue to expand. The influential Carnegie Report – Educating Lawyers: Preparation for the Profession of Law (Sullivan et al, 2007) identified a critical need to reform legal education to integrate knowledge, skills and values while at law school. Developing a reflective practice model could be a critical contributor to this need for integration. A Canadian law school reforming their upper year curriculum has identified a “reflective approach” and a reflective practice model as a key component of their three-pronged reform strategy which also includes “outcomes-driven” and “integrative” approaches to learning. An overview of the working definition Reflective practice has been described and understood in many different ways in the literature and in practice settings. It is important to establish a working definition to represent what it means in the context of developing legal professionals. To begin to conceptualize it, I incorporated three important aspects of developing reflective capacity. The first aspect is based on the original “instrumental” model popularized by Donald Schön (1983) which represents the importance of professional education including reflective practicums to help students integrate theory and practice, and to encourage the habitual practice of learning from experience for professionals. The second and third aspects illustrate the importance of developing the skills of critical reflection and self-reflection. The Venn diagram below with its three intersecting circles symbolizes the need to integrate all three aspects to develop an “integrated” Reflective Practitioner (IRP), An IRP is self-aware and can reflect on practice and critical theory as a self-directed life-long learner, often engages in collaborative reflection, and takes action to improve her/his professional practice. The benefits of developing a discipline of reflective practice apply to every stage of professional development from the novice law school learner through to the professional expert. The benefits also apply to all types of legal professionals including law students, law faculty, lawyers in practice, and those who practice law in other conventional and non-conventional ways (mediators,researchers, policy makers etc.) 2 Reflective practitioner (technical) Critically reflective practitioner Self-reflective practitioner Integrated Reflective Practitioner The (conventional) reflective practitioner (RP) In 1983, Donald Schön first coined the term reflective practitioner” in his seminal work The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. He described reflective practice as “a dialogue of thinking and doing through which I become more skilful” (Schön, 1987, p.31). Professionals must be helped to learn the “artistry” of their profession by progressively gaining knowledge about how to deal with complexity, indeterminacy and value conflicts. They must be able to apply technical knowledge in the “swampy lowlands” of actual practice – “confusing messes.” The capacity to “reflect-in-action” and “reflect-on-action” develops professional expertise through a rigorous and disciplined learning experience and builds reflective judgement. Later authors have asserted that developing capacity for “anticipatory reflection” before action is also crucial. This approach is synonymous with experiential, self-directed and action learning. Reflection on experience deepens learning and increases resiliency and effectiveness. At a minimum, this approach is intended to improve one’s technical practice by integrating theory and practice, and knowledge and skill. Critically reflective practitioner (CRP) A second aspect of the model is developing skills at becoming critically reflective. This includes the need to be constantly vigilant about unpacking assumptions and questioning our frames of reference or “mental models.” Ideological critique, deconstruction, consciousnessraising, unmasking power and privilege, and creating emancipatory knowledge also exemplify this aspect. A critically-reflective practitioner questions the status quo, understands law as a social construct, is curious about alternative conceptions of the role of law, is aware of legal pluralism, and engages in critical legal studies including poverty law scholarship, feminist and critical race theory. Furthermore, when learners are exposed to “disorienting dilemmas” (disturbing facts or information or critical theory that contradicts their earlier understanding), critical reflection can support transformative learning and shifts in perspective. Critical reflection appears to be strongly nurtured at the law school where I undertook my research, and the impetus to increase a critically reflective stance underlies much of the current curriculum reform. This type of reflection can tap into and support a nascent inclination for social justice, developing a perspective on professional responsibility that includes a desire to increase access to justice. 3 Self-reflective practitioner (SRP) The third aspect of reflective practice is developing the capacity to be self-reflective. Encouraging this capacity is fundamentally important to developing a personal vision or an explicit philosophy of practice, and to integrate professional knowledge, skills and values. This type of reflection fosters professional and personal integration. Self-awareness and a capacity for self-regulation support ethical and moral development, and contribute to civility. Self-knowledge and open-mindedness (“enlargement of mind”) help build intercultural competence, and an ability to work productively and creatively with others, supporting emotional and social intelligence. Furthermore, healthy self-reflection and self-care can help foster a stable work-life balance, increase personal coping strategies, and support improved emotional, mental, physical and spiritual health. Healthy self-reflection leads to increased selfefficacy and commitment to act on what one believes in. Reflection on learning and learning needs nurtures self-directed learning which in turn will support a desire for life-long learning. Being able to reflect on one’s strengths and weaknesses, to learn from constructive criticism, and to develop new strategies are important outcomes of self-reflection. The integrated reflective practitioner A growing synthesis between all three aspects develops an “integrated” reflective legal professional. It is possible to envision reflective activities helping to move one along a spiral of learning – touching on instrumental, critical and self-reflective aspects. New perspectives and actions are informed by this learning spiral. Reflective practice becomes a way of being, supporting a life-long journey of learning, professional growth and commitment to action. Reflective practitioners are committed to making changes to their practice based on what they have learned through all three types of reflective activity. Additionally, they reflect in community, subjecting their reflection to scrutiny by peers. Additional resources to inform our discussion I developed mind maps to explain why reflection and reflective practice are important learning and professional development tools for law students and legal professionals. (See Mind Map # 1 – Potential Outcomes of Reflection and Reflective Practice in the Resource Kit for Reflective Practice.) I also used one to organize the multiplicity of potential methods to encourage student reflection (See Mind Map # 2). There are many opportunities at law school to encourage reflection from the initial application process, to orientation, and on through to graduation (See Mind Map # 3). A pervasive approach to encouraging reflective practice would be most beneficial. In my view, the learning environment at law school is very rich and the potential for fostering more reflection is robust. To demonstrate the complexity and depth of the concept, I compiled a collection of quotes about reflection and reflective practice that can be found in the Resource Kit. To place reflection and reflective practice in the context of adult and higher education terminology, I have also developed a Glossary of Terms. The PowerPoint presentation provides an overview of some of the findings of the research project including some of the ideas and practices to encourage law student reflection that were shared by the eight professors I interviewed. 4 A simplified definition: A legal professional who: Learns in action and is constantly improving his/her technical competence through reflection on experience and action and learning from his/her practice Has the capacity, knowledge and desire necessary for critical reflection (in the many manifestations which could include ideological critique, critical thinking, unpacking assumptions and mental models, alternative conceptions about the role of law, enlarged conception of “access to justice,” critical legal studies including poverty law scholarship, feminist and critical race theory, legal pluralism, etc.) Is self-reflective (implying a personal vision, a philosophy of practice, personal and professional integration, growing emotional and social intelligence, ongoing ethical and moral development, self-aware, self-directed, self-regulating, able to articulate one’s core values, etc.) Reflects in community, and can engage in collaborative reflection. Prepared by: Michele Leering, 2009 LFO Community Leadership in Justice Fellow & Executive Director/Lawyer with Community Advocacy & Legal Centre, Belleville, ON, Canada leeringm@lao.on.ca 5