Partners of Industry-Jedediah Strutt and Richard Arkwright

advertisement

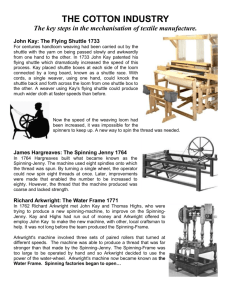

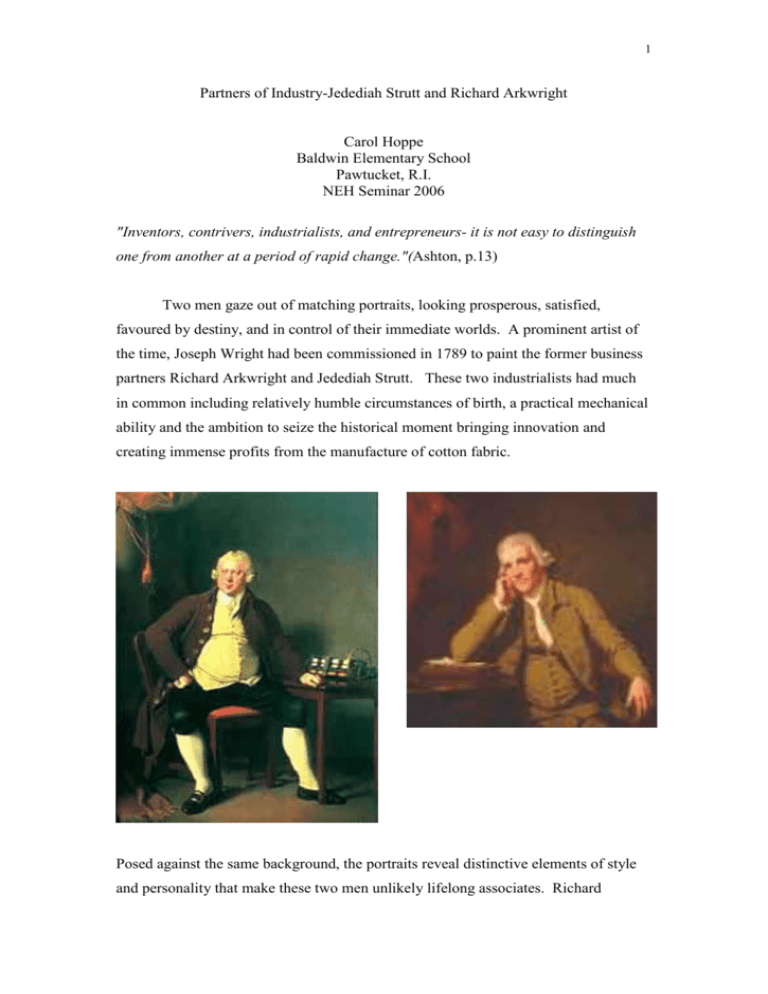

1 Partners of Industry-Jedediah Strutt and Richard Arkwright Carol Hoppe Baldwin Elementary School Pawtucket, R.I. NEH Seminar 2006 "Inventors, contrivers, industrialists, and entrepreneurs- it is not easy to distinguish one from another at a period of rapid change."(Ashton, p.13) Two men gaze out of matching portraits, looking prosperous, satisfied, favoured by destiny, and in control of their immediate worlds. A prominent artist of the time, Joseph Wright had been commissioned in 1789 to paint the former business partners Richard Arkwright and Jedediah Strutt. These two industrialists had much in common including relatively humble circumstances of birth, a practical mechanical ability and the ambition to seize the historical moment bringing innovation and creating immense profits from the manufacture of cotton fabric. Posed against the same background, the portraits reveal distinctive elements of style and personality that make these two men unlikely lifelong associates. Richard 2 Arkwright is a corpulent man, dressed in fashionable attire woven of rich, luxurious fabrics. He is posed with a model of his spinning machine including the end product, spools of tightly spun cotton thread. Arkwright peers out into the distance, one hand cocked at his hip, almost straddling the chair. His appearance (as well as his history) suggests a commanding personality, one who has tasted the riches of his world and intends to continue doing so. Jedediah Strutt is a quiet image, dressed in plain brown cloth and a white shirt. He occupies the frame turned to the side, chin resting in his hand, displaying a contemplative nature, he is posed in the company of books and papers suggesting values of education and philosophy. His portrait is considerably darker and more sombre in tone, he appears to be a solid presence, sure of his priorities, consistent in the way he works and lives. Silk stockings and wigs were the unlikely starting place for this partnership of 13 years duration. As with their business interests, their individual stories convene and diverge. Together with other partners, they pioneered the establishment of an enterprise in Cromford, which was the first water-powered cotton spinning mill allowing for the mass production of cotton warp threads, thus making possible the machine production of cotton calicos. This is the one industry acknowledged by all of our expert authors to be the source of staggering growth and technical innovation that sparked the changes that we refer to as the Industrial Revolution. Jointly and individually, directly and indirectly, both men went on to influence the formation of other mills responsible for the working lives of countless women and children. “However they are looked at, the cotton factories of Arkwright and his partners and licensees in the late ‘70s and 80’s were remarkable pieces of industrial organization which gave immense impetus to the factory system and the use of water power.” (Fitton and Wadsworth, p.91) A considerable body of correspondence and business records of J. Strutt have survived the centuries. There exist personal letters and drafts of business correspondence going back to the courtship of his wife, addressing issues with his children, his business partners and of course, Arkwright himself. This correspondence provides the material that is the basis for a book by R.S. Fitton and A.P Wadsworth. It seems fitting with Strutt’s frugal nature that he would save his records and letters. Unfortunately, also consistent is the lack of first person 3 information on Arkwright, who was secretive by nature and guarded his advantage with misdirection and slights of hand. When working on the mechanics of his spinning frame, Arkwright deliberately spread the story that he was developing a machine to determine longitude. One of the initial attractions of the location of Cromford for his first mill was the seclusion that would buttress his desire for secrecy. Jedediah Strutt, (Jerry to his wife) was born in 1726 near Alfreton, the son of a small farmer and his wife. Alfreton had an active community of Dissenters and this connection with the Dissenter religious and business community was a shaping factor in his personal values and his business success. In Credit Where Credit Is Due, James Burke characterizes Dissenters with entrepreneurial training, optimism, profit orientation, piety, schools and valuable business networks. Although not highly schooled, all of these other characteristics seem to have been significant elements of Strutt's success. At age 14 he was apprenticed as a wheelwright, a profession identified by Maxine Berg as an early technology training ground. During that 7-year period he boarded with a Dissenter family, the Woolarts, who were instrumental in his business life. The family had nonconformist intellectual connections and it was his first wife, Elizabeth Woolart, who maintained this network. During their long (7 more years) courting, Elizabeth worked in London and this proved useful when Jedediah was seeking capital and markets. The Woolart connection also brought Strutt into collaboration with a brother of Elizabeth, William Woolart who guided Jedediah's mechanical skills toward the hosiery business that was centralizing in the Derby and Nottingham areas. 1758 was a milestone year for Strutt. He filed his first patent, formed his first partnership and began operating as a middleman in a putting out business that supplied materials, machines and markets for independent small-scale hosiery manufacture. His invention, the Derby Rib Attachment, modified the stocking frame, invented by Reverend William Lee in 1589 as a tool for cottage industry. The Rib Attachment produced a stocking with vertical ribs that followed the shape of the leg, improving the fit and the appearance of the stocking. The idea for the machine originated with another man described only by surname, “Roper”, also described as “an indolent fellow”. Roper apparently never got to the point where he had a 4 practical, working model of his machine. Strutt modified this invention and filed a patent for his own Rib attachment. William Woolart and Samuel Need (of the Dissenter network) were his partners in this venture. The patent was challenged in 1765 with Strutt emerging victorious. The success of the Derby Rib Attachment moved Strutt to another plane of the Industrial Revolution; he was selling machinery and methods instead of producing an end product. This invention allowed Strutt to accumulate the capital that propelled him into the next phase of his career. Need and Strutt formed a partnership with Arkwright in 1769 at the moment when Arkwright was filing a patent for the spinning frame. Their investment of £500 bought them 1/5 interest and may have provided the money needed to pay the fees to complete the patent application for the spinning frame. (Fitton and Wadsworth). The partnership then proceeded to purchase land in the Cromford area even before they had a fully working model of the spinning frame. Strutt seems to have been an active partner although Arkwright was clearly in control of Richard Arkwright and Co. In 1774 Strutt successfully lobbied Parliament for a reduction in the excise tax on calicos. This opened the market for their product. More mills followed, Maxine Berg noted that even these partners initially preferred to open a number of mills of relatively limited size rather than fewer, larger mills. This same year, Elizabeth Strutt died. She had been an important factor in his early success as well as a confidant. She made trips to London without her husband to promote business interests. Later Strutt’s two daughters as well as the three sons worked in the business. Strutt remarried in 1781, choosing a widow from the Dissenter community. In 1782 Strutt and Arkwright were successful co-defendants in a patent defense of the spinning frame. Also that year they dissolved their partnership. The precipitating event was the death of one the partners, Samuel Need, and the need to resolve his investment. Arkwright seems to have had difficulty getting along with his partners almost from the beginning and probably resented dividing the profits. At one point Strutt writes of this problem to fellow partner, Smalley. "We cannot prevent him saying Ill-natured things nor can we regulate his actions, neither do I see that it is in our power to remove him otherwise than by his own consent for he is in possession and as much right there as we." (Fitton and Wadsworth, p. 75,76) At one point 5 Arkwright considered selling all rights to the water frame to Strutt and Need for £1000. Strutt, being more cautious, believed the partnership to be overextended. No doubt, life was easier for both partners after the dissolution, but they continued socializing and the two families often spent holidays together. Strutt took over mills in Belper, Milford, and Derby; Arkwright focused on Cromford (including Masson), Wirksworth, and Nottingham. In the late 1780’s young Samuel Slater served as an apprentice to Jedediah Strutt at Milford and Belper. By travelling to N.Y., then R.I. on a clandestine mission, he managed to take plans for the machinery and factory management system to N. America, opening Slater Mill in 1793. In both business and personal lifestyle Slater followed the example of his former master and mentor. (He found religious minority (Quaker) partners, used the family model in recruiting employees, required a minimum age of 7 years old and provided mill classes for child workers, married into the family where he boarded, eventually preferred individual ownership of mills.) By all accounts, the Strutt family lived modestly but well, having houses in Milford and Derby within sight of the mills. In Belper he built the Unitarian Chapel, still used today, he also made contributions to all of the religious congregations in the towns where he owned mills. Jedediah and his sons were major philanthropists in all three communities, contributing major public works such as parks, arboretums, gas lighting, schools, and art galleries. The eldest son, William became a well-known industrialist in his own right and is best remembered for innovations and improvements in mill design to render them more fireproof. The Strutt children were socially prominent and had close social relationships with Erasmus Darwin, Samuel and Jeremy Bentham, Robert Owen, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Jedediah died in 1797 at 70 having accumulated a fortune of £160,000. He wrote his own epitaph, claiming for himself "without having wit had a good share of plain Common Sense-Without much genius enjoyed the more Substantial blessing of a Sound understanding..." Richard Arkwright presents a radically different personality, lifestyle and a more significant place in the history of industry. Born in 1732 in Preston, he was the son of a poor, large family supported by a tailor. Richard was taught to read by his 6 sisters, but appears to have had no formal schooling, he apprenticed and worked as a barber and wig maker. He married Patience Holt in 1755, had a son Richard the next year and lost his wife the following year. Problems maintaining family relationships were a lifelong pattern. It is likely that there were issues with the family of his first wife (she was buried in the plot of her birth family with no mention of her married name). (Mason, p.1) In 1761 he remarried and his daughter Susana was born in 1761. Arkwright and his second wife were estranged and lived apart for much of their lives. He was also alienated from his son for a period of time after the son's marriage. Richard Arkwright also apparently had little to do with his mother; she became a recipient of public charity for a number of years. Arkwright purchased a pub in 1762, but could not make it successful and returned to barbering. A turning point in his career came in 1767 when he met and eventually hired John Kay, a clockmaker. Kay was a neighbour of Thomas Highs who had the earliest known idea of using machine rollers to spin yarn. Highs never completed a working model but it seems likely that the idea migrated from Highs to Kay to Arkwright. Arkwright and Kay worked in secrecy through 1768 and 1769 at which time Arkwright applied for a patent. Arkwright was obligated to take on partners to move his invention forward. In 1769 Strutt and Need joined his endeavour. It appears that the partners themselves had no firm idea of the scope of their improvements. In a letter dated 1772, Arkwright rhapsodises "wee shall not want 1/5 of the hands I First Expected" (Mason, p3) Cromford was a stunning, profitable success both in terms of the manufacturing efficiency and the quality of the product. They had originally planned to sell the cotton yarn to hosiers but it soon became apparent that the spinning was so tight that for the first time cotton could be used as weft and a much lighter, 100% cotton fabric was possible. "Roller spinning remained an idle discovery ‘till Arkwright took out a patent for a roller –spinning frame, worked by water power, in 1769. This water frame…produced a stronger thread than the wheels or jennies, a thread that could be used for warp; thus it was now possible to manufacture pure cotton goods…" Hammonds, SL, p51. The key to Arkwright’s spinning frame was that the space between the rollers could be adjusted to reflect the different length of staple in different types of cotton. Arkwright was 7 cagey and jealous of his ideas; in order to keep the lid on imitative efforts he restricted the sale of the water frame to industrialists with mills of 1000 spindles or more. This is the major reason that Berg gives for the different configuration of the cotton industry. "It was the Arkwright-type mills which marked the really big divide. These were thousand-spindle mills built to use Arkwright's newly patented water frame...this centralization was not caused by the development in technology. It was caused by key business decisions." (Berg p.230) Almost immediately after Cromford began running smoothly relations between partners became difficult. "Arkwright was a domineering, self-sufficient man and the relations with his partners was not easy." (Fitton and Wadsworth, p 76) Other industrialists generally disliked him although he commanded loyalty among many of his workers as evidenced by the militia of workers who formed to guard Cromford after Brikacre was destroyed by rioters in 1779. By 1774 William Strutt wrote to his father, "You begin to be much wanted at home and may also be at Cromford; I was there... and heard very unfavourable accounts of Mr. A.’s behaviour, I suppose he is going to leave you." (Fitton and Wadsworth, p. 75) After the death of Samuel Need in 1782, Strutt and Arkwright parted company but remained business allies and social contacts throughout their lives. Beginning the same year Arkwright filed a series of lawsuits defending his patent rights from interlopers (smaller manufacturers who did not have 1000 spindle operations). In 1785 the issue of the originality of the invention resulted in the loss of his lawsuits. The defeat left him enraged and bombastic. Matthew Boulton (of Boulton and Watt) reported “he swears he will take the cotton spinning abroad and that he will ruin those Manchester rascals he has been the making of "(quoted by Fitton and Wadsworth, p.98). By 1786 Arkwright’s long held social ambitions began to be realized however. He was awarded knighthood in 1786 and made High Sheriff of Derbyshire the following year. The ostentatious style that he brought to the office was legendary, including 30 richly dressed javelin men as an honour guard and a fine carriage with four matching grey horses. He had begun rebuilding Willersley Manor in 1782 but lost it to fire and did not live long enough to reside there. Arkwright did achieve the social prominence that he craved and in later years was a social peer of the 8 Nightingales and Erasmus Darwin. Arkwright’s actual residence in Cromford, Rock House was perched on a rock face that allowed him to overlook his kingdom; the mills and mill village that he was instrumental in creating. Arkwright died in 1792 at 60 years old. At the time of his death he had accumulated £500,000. He was living apart from family and commonly kept a working day that went from 5:00 AM to 9:00PM. Similarities and Differences Although extremely different in personality and temperament, Arkwright and Strutt shared many characteristics. Both men came from relatively humble family backgrounds. Each developed mechanical inventions using other men’s ideas as the springboard. Each invention was part of a process of innovation that extended from an existing industrial tradition. Both were well qualified to take advantage of the particular era in which they lived. They each survived the initial patent challenges although Arkwright eventually lost his patent cases by aggressive pursuit of other textile manufacturers. They each launched their families into fortune and social prominence. They used the same model of mill and workforce organization. The worker housing both provided followed the same basic plan and was of such quality that it is still used. They established a minimum and maximum age for their workers and promoted schooling and religion. Each industrialist used innovative worker incentives to keep production high. Their differences included their personal religions Arkwright was of the majority religion, Church of England, while Strutt was a Unitarian. Strutt was a family man who found satisfaction in plain living and family life, while Richard Arkwright had little sustained contact with his family. Strutt seems to have been regarded as intense, serious, gentle and ethical. Arkwright was widely disliked by other manufacturers and presented a brash, boisterous image. Strutt was the more conservative businessman; he also extended more benefits to his workers and engaged in substantial philanthropy. Treatment of Workers 9 "According to their lights and in the atmosphere of their times both the Arkwrights and the Strutts were good employers." (Fitton and Wadsworth, p.225) It is difficult to engage in comparison between the two men as employers because written record is available on the Strutt Mills and so little remains of the Arkwright business records. The two industrialists provided quality housing, of course, housing was a way to attract workers in numbers needed for the scale of their factories, but it would seem that both men went beyond what was merely necessary. In an effort to regulate health, Strutt’s worker housing at Belper was whitewashed regularly and the chimneys cleaned every 3 months. Both employers supported and built schools. Strutt required child workers to read, write, and count. Classes were available and required for two hours a day in the mill. Both industrialists used a work schedule consisting of a 12-hour workday and ran their mills day and night. According to the North Mill museum display, Strutt provided medical care and sick days through a "sick club" that lasted for six years before being disbanded. He also paid compensation to workers injured on the job. "This type of economy was seen at its best in some model establishments like those of the Gregs or the Ashtons or the Strutts, where the capitalist supplied church, school and reading room." Hammonds, TL, p. 42) Legacy "Whoever says Industrial Revolution says cotton. "This is the first sentence in Eric Hobsbawm's third chapter. The consensus among our course's authors is that whoever says cotton says Arkwright. "Arkwright's achievement was to combine power, machinery, semi-skilled labour, and a new raw material to create, more than a century before Ford, mass production" (Mason p. 7) Richard Arkwright is generally credited with one of the three pivotal inventions that brought the cotton industry into its place of prominence in the course of events that led the early Industrial Revolution. Of equal importance was the management style and employment practices that created one of the first worker communities. Arkwright’s effort to protect his patent by selling spinning frames only to large industrialists (1000 spindles or more) was a crucial factor. Maxine Berg identifies this as the reason that the cotton industry presented a different structural 10 pattern from the other textile industries. "It was Arkwright's patent which enclosed the machine within a factory, had it built only to large-scale specifications, and henceforth refused the use of it to anyone without a thousand-spindle mill." (Berg, p. 241) Both Arkwright and Strutt possessed great, practical mechanical aptitude. They used these skills to create their inventions that originated with the ideas of other men. It is somewhat puzzling that both men borrowed or poached the initial idea for their inventions without giving credit to the originators and that they seem to have had no qualms about doing so. Arkwright was an opportunist, but Strutt was an individual who made moral rectitude and generosity a defining part in his personality. I believe that his efforts to improve working conditions and living conditions were the result of his sincere religious belief as well as his idea of sound business practices. Part of the answer to this dilemma lies in the standards of the times and with the abhorrence of waste and laziness which seems to have been a prominent feature of British society in that era. Strutt describes Roper as “an indolent fellow”, as if that says it all. Arkwright’s testimony in his patent defence includes this statement “Suppose if any man has found out a thing, and begun a thing, and does not go forwards, he lays it aside… another man has the right to take it up, and get a patent for it.”(quoted by Mason, p. 2) There was the idea that industrial progress was similar to a force of nature and must inevitably be moved forward. If the originators of the technical ideas were unable to use them productively, someone else had to. Jedediah Strutt was responsible of a family of innovators and philanthropists “the Strutts of Derbyshire supplied not only schools and library, but a swimming-bath with an instructor, and a dancing-room.” (Hammonds ,TL p. 49) Jedediah Strutt and Richard Arkwright were among the first generation of selfmade industrialists to arise in Britain. They occupied a place that was without precedent in both occupational and social spheres. Arkwright in particular had an unusual background and was highly atypical in the extremity of his rise and the loneliness of his situation compared to other industrialists. It is little wonder that he had difficulty behaving gracefully. The two men were products and manipulators of their place and time. While it is difficult to enter fully into the spirit of that time, some conclusions seem clear. The fundamental inventions of the era were part of a 11 long progression of attempts to solve vexing production and technology problems. Neither of these two entrepreneurs was responsible for the original seed of the idea for their inventions. Their significant contribution was to create usable, factory-ready versions of the machines that made their place in industrial history. It may be that equal historical value should be given to the organisation of worker communities, the use of alternative (non- animal) power and the use of women and children as workers. As employers and industrialists, Arkwright and Strutt need to be judged by the standards of their period. In this regard they did better than many others in creating settings that were successful and somewhat progressive (for their times) places to work. Strutt is particularly noteworthy in the variety and scope of benefits to community and individual workers. This being said, all the mills employed standard work practices of hiring children, 12-hour days and limited safety measures. Arkwright and Strutt have left evidence of their careers, their personalities, their ethics and their contributions in the history of industry, the story of their succeeding generations, and the towns that attribute their existence to the textile mills they originated. In an ironic twist, their remaining companies were bought up by the English Sewing Cotton Company in 1958, one hundred seventy six years after being split apart. 12 Bibliography Ashton, T.S., The Industrial Revolution, 1760-1830, Oxford,U.K.: Oxford University. 1948 Berg, Maxine, The Age of Manufactures1700-1820, Industry, Innovation, and Work in Britain, 2nd edition, N.Y, N.Y.: Routledge. 1994 Chapman, Stanley, The Early Cotton Masters, Newton Abbot, U.K.: David and Charles.1967 Fitton, R.S.,, The Arkwrights, Spinners of Fortune, Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University.1989 Fitton, R.S. and Wadsworth,,A.P., The Strutts and the Arkwright 1758-1830A Study of the Early Factory System, Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University.1958 Hammond, J.L. and Barbara, The Skilled Labourer, London, U.K.: Longmans.1919 Hammond, J.L. and Barbara, The Town Labourer, London, U.K.: Longmans.1917 Hobsbawm, Eric, Industry and Empire, N.Y.N.Y.: New Press. 1968 Mason, J.J., Oxford DNB, http://via.oxforddnb.com/articles/0/645-article.html Mason, J.J., Oxford DNB, http://via.oxforddnb.com/articles/26/26683-article.html Power, E.G., Belper, First Cotton Mill Town, Belper, U.K.: Belper Historical Society. 1999