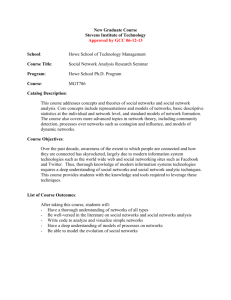

Thesis structure

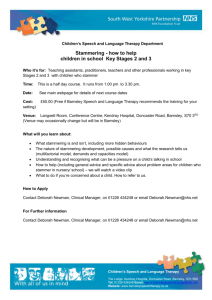

advertisement