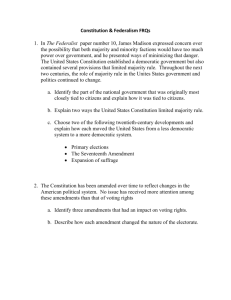

U.S. Democracy: Key Readings & Documents

advertisement