The Web and Model-Centered Instruction

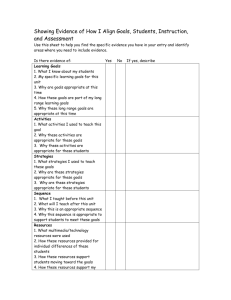

advertisement

The Web and Model-Centered Instruction Andrew S. Gibbons Kimberly Lawless Utah State University Thor A. Anderson Netscape Joel Duffin Utah State University Information and Instruction Both economy and effectiveness will determine the future success of the Web as an instructional distribution channel. The instruction the commercial web delivers will have to be powerful, but it will also have to be affordable. Consider the effectiveness issue. The web is today without dispute the world’s premier information system. But what will it take to make it the premier instructional system? That answer has to take into account the difference between instructing and informing. For our present purposes, we will define instruction as the engagement of two or more individuals’ wills or plans in a cooperative effort to first establish and then verify new personal meaning and performance capacity. Verification—the search for evidence that learning goals have been attained— distinguishes instructing from just informing. You are never tested to see if you learned what the newspaper informed you about, but you must demonstrate performance ability and the attainment of certain knowledge before you can be certified in an area of professional practice. During instruction, two individual wills negotiate learning and performance goals and then work in concert to achieve them. Sometimes the goals are unspoken and sometimes they are explicit, but they always exist, if it is instruction. What makes instruction effective? That question has been the center of a great debate, and some useful new answers are emerging. One thing certain is that instructional techniques that have been used regularly for years are being joined by new ones. Perhaps a better way to put it is that instructional methods that have been given low priority in the past are now being rediscovered and given much higher priority: at the same time, some of the old standbys are being given lower priority. The standard forms of the past 30 years are only a small subset of the possibilities that can be generated by considering new instructional roles, activities, formats, and relationships made possible by these newlyemphasized methods. Recent developments to remove some of the old assumptions of instruction emphasize the importance of the social context of learning (Collins, Brown & Newman, 1987; Rogoff, 1990), learning by problem solving (Barrows, 1985, 1992), and the situation of learning in realistic contexts (Lave & Wenger, 1991). These trends are closely related to an evolving instructional viewpoint called model-centered instruction (Gibbons, 1998; Gibbons & Fairweather, 1998; Gibbons & Anderson, 1994). Model-centered instruction, which is described later, involves an instructional relationship consisting of a learner and a companion-in-learning who together observe and interact with one or more real or modeled environments, cause-effect systems, and/or samples of expert behavior. The companion supplies instructional support in a variety of forms and through a variety of roles as the learner solves a series of problems of escalating difficulty defined with respect to a set of models or systems of escalating complexity. The work of White and Frederiksen (1990) summarizes principles for defining externalized instructional models, from which learners can construct corresponding internalized mental models. The import of model-centering is that it assumes experiencing a model or a system in some form as a primary instructional means. Model-centering assumes also that a secondary, companion function accompanies that experience in ways that guide and support learning. How can the Web make the transition from offering almost exclusively informational services to accommodating a greater share of truly instructional ones? This will entail considerable change: (1) a new web designer mindset changed from traditional instructional views to ones that incorporate model-centering, and (2) tools of new kinds not widely used yet, even for the development of stand-alone (non-web-based) computerbased instruction. As new instructional viewpoints such as model-centered instruction emerge to bring out the unique strengths of the computer as an instructional tool, they will broaden the computer’s traditional role to include new uses as a multi-purpose tool (Lajoie & Derry, 1993). To tease out the implications of the instructional web, let’s look at computerbased instruction in terms of its internal structures. Instructional Considerations: Convergence of Instructional and Logical Constructs An instructional designer, through the act of designing, builds abstract event structures that embody strategic plans. An event structure may consist of a presentation of information, a quiz, a practice exercise, a problem to solve, a demonstration of performance, or one of numerous other options. The designer designs these event structures so that a learner can have goal-relevant experiences. In order to move from design to product, designers must match these event structures with the expressive and interactive structures supplied by—and unique to—the medium they are using for instruction. Books supply page structures; computer-based authoring tools supply programming structures like control or decision points, icons or frames, branching, graphic objects, and text objects. The most important issue for computer-based instruction of all kinds—including web-based instruction—is the convergence zone shown in Figure 1. This is the place where the designer’s abstract instructional constructs and the concrete logic constructs supplied by the development tool come together to produce an actual product. At this point, the abstract event constructs are given expression—if possible—by the constructs supplied by the development tool. This zone is especially critical for computer-based instruction because CBI demands explicit and detailed specification of logical structures to a degree required by no other medium. Other media depend heavily on pre-sequenced blocks of content, message, and representation. The computer is capable of computing a sequence of events for individual learners. Attention to the convergence zone by CBI designers is crucial because the zone moderates: (1) the exactness with which the designer’s strategic plans are implemented and (2) the time and effort required for developing the instruction. The convergence zone is where the effectiveness and the cost of the instruction are mostly determined. Figure 1 shows that computer logic constructs are supplied by specific development tools and tool families. For instance, a frame-based tool supplies different types of frame (subroutine) logic. An object tool supplies generic objects that can be customized by the user to perform specific functions. Here is what happens at the convergence zone. The theoretic or paradigmatic orientation of the individual designer causes certain kinds of instructional construct to appear in his or her designs. The development tool chosen determines the logic constructs that will be available for use. The match or mismatch between the designer’s instructional abstractions and the tool’s logic structures at this point either constrains or supports the degree of implementation of the design. Since even software tools are maximized for certain uses and minimized for others, it is almost unavoidable that a given development tool will either express or restrict a given instructional event plan. This phenomenon has led in the past to a restriction in the designs themselves and encourages a kind of conformity to the tool rather than an expression of more powerful and effective designs. This pattern from the past needs to be reversed, and the instructional Web may be an opportunity to do so. Instructional Paradigm Development Tool Instructional Constructs Tool Logic Constructs Zone of Convergence Figure 1. Factors that define a convergence zone where abstract instructional constructs and logic tool constructs meet in computer-based and web-based instruction. In terms of abstract design constructs, the Web’s current metaphor is the network of hyperlinked documents and resources. Web tools provide logic constructs that match this metaphor perfectly. With a web tool you can construct web pages (of the document) with special formats provided by HTML. Pages are populated with various textual and graphic information resources and can provide special effects and interactivity using applets and controls, which are simply types of resources. Links or hotwords are the paths that tie pages together. The design constructs used for web pages for the most part correspond directly with the tool constructs provided by web development tools, and if the informational metaphor of the Web was also a suitable instructional metaphor, then the transition to the instructional Web using existing tools would be smooth and uneventful. But informing is not instructing, and so a significant shift toward instructional development tools for the web can be expected, and that may pose some difficulties to the mindset of designers and to the formation of development tools. The shift will involve not just web page construction tools but the information-linking design constructs now firmly implanted in the minds of tens of thousands of Web designers. These patterns of thinking and designing may in the short term hinder the use of the Web for highly interactive instruction, because they conflict with the instructional constructs that must come to share the Web. Let’s examine two prevailing views of instruction in more detail and the tool requirements they entail. Two Instructional Paradigms Hannafin and his associates (Hannafin, Hannafin, Land, & Oliver, 1997) provide an excellent description of two major views of instruction in their discussion of instructivist versus constructivist instructional approaches as foundations for instructional designs. These two major views of instruction lead a designer to apply much different abstract instructional constructs in their designs. The task of expressing these two families of constructs in the form of computer logic brings the designer face to face with two different families of logic structures. Gibbons and Fairweather (1998), for instance, define multiple, nested levels of construct that are involved in direct, or tutorial, instructional designs (see especially pp. 171-180 and 421-462). They define four levels of design construct: a strategic level, a content level, a message level, and a representation level. At each of these four successive levels, abstract design constructs from the previous level unfold to create a complete and detailed design, whose structures at the lowest level must in some way be made to correspond with the logic structures supplied by some authoring tool. This is the convergence zone. (Keep in mind that for the present moment we are focusing on direct, tutorial, strategy-centered instruction. What we are saying does not apply to the second type of instruction defined by Hannafin, which we will treat in a moment.) At the highest level of design construct (the strategic), the structure consists of a strategic plan divided into functional sub-constructs (for instance, “present information,” “provide an appropriate demonstration,” “provide practice”). Each of these strategic subconstructs splits along the lines of content structure to produce smaller constructs (“present one example of a concept class” or “practice of one step of a procedure”). These content-tempered sub-constructs break down further to produce message subconstructs (“present the definition of the concept,” “present one example,” “present one paired non-example”). Message-tempered constructs unfold one more step to produce representational sub-constructs (“provide the text portion of the definition at the appropriate screen position and at the right timing,” “accept the learner’s response to the non-example and check it”). It is at this lowest level of detail, the representational, that the structures, which to this point have been only conceptual and involve an abstract design, are made to correspond with the reality of some set of logic structures supplied by an authoring tool. Displaying the text for the concept definition may involve presenting a text string, a bitmap, or a fixed string in some typeface at some size, and at a particular place on the display. Accepting the learner’s response involves specifying several items of information: location of the response, type of response, disposition of the response (stored or not stored), appearance of the response on the display, and so forth. The authoring tool may or may not provide the type of service the author envisions. If it provides it, it may be easy (inexpensive, modest skill) or hard (expensive, high skill) to arrange. At this convergence zone and in this way, the authoring tool influences the cost and effectiveness of designs. Hannafin and his associates identify a second type of indirect instruction that relies more heavily on direct experience supplemented by coaching and other forms of learning augmentation activity. The constructs required to create this type of instructional experience differ considerably from those for direct instruction. They include: environments in which a problem can be posed and solved; the data and representations related to the problems themselves; interactive cause-effect systems (computer models) that can be manipulated during problem solving; systems of expert behavior that can supply models of performance for learners to observe; resources that supply content for problem solving; dramatic overlays that situate problems in realistic contexts; recording and analysis tools for the collection and manipulation of data; communication tools; and auxiliary instructional features that supply the functionality of a learning companion. These abstract design constructs can be subdivided and eventually matched with the logic constructs of the tool that will give them life, just like direct instruction constructs, but the indirect design constructs break down in different ways. For instance, environments for problem solving normally divide into individual locations (real or metaphorical) that can be “visited” to obtain information that is available there; pathways connect these locations, implying the need for movement controls. The representations used to display locations and their information ranges from simple textual presentation at one end of the spectrum to virtual experiences at the other, and the range of options between these extremes includes every form of representation available to computers and all combinations of them. The other high-level constructs listed earlier for indirect instruction break in similar fashion into sub-constructs in their own ways, but the goal of the reduction process is the same, whatever the structure, and whether for direct or indirect instruction: to produce a set of abstract design structures that can be matched with the logic structures offered by the development tool of choice. Since the constructs for indirect instruction differ from those of direct instruction, it turns out in many cases that the logic structures supplied by authoring tools designed primarily for direct forms of instruction match poorly with the abstractions created for indirect forms of instruction. This will prove to be the greatest challenge for the instructional Web. Tool Implications The benefit obtained from specialized web authoring tools is not just functionality but productive functionality. Increased productivity is the primary reason for building such tools. If no authoring tools existed, the designer would be required to use a highlevel programming language like “C.” In fact, some organizations do use high-level languages despite their higher development price tag because they have had a chance (paid for by volume production) to design their own set of specialized routines (logic structures) that can be strung together according to need to match a set of standardized design constructs. In effect, they have constructed their own special purpose authoring tool. Many large training software vendors are positioning themselves and their products to be web-compatible in this way. Likewise, virtually all major commercial authoring tool vendors, seeing the potential (can we say inevitability?) of the Web as an instructional channel, are migrating their products toward web compatibility and web-friendliness. Instructional designers now face difficult tool choices and wonder if there is a best choice that will not require future adjustments and re-programming of their products. Even more important, many are wondering how they will be able to implement a newer instructional paradigm (indirect instruction) in a medium that is not yet fully compatible (in terms of productivity) with the high interactive demands of the old paradigm (direct instruction). Examining the Web’s Underlying Metaphor More Closely During the coming period of transition, where the Web will try to embrace interactive instruction in addition to information access, it is a good time to reconsider the basic structural metaphors of instruction and to compare them with the structural metaphor of the Web and its tools. We should ask, “Can we see a clear path for the creation of Web development tools that will implement today’s instructional metaphors and allow for their future growth in feature and function?” We believe that the answer to this question begins with a closer inspection of the language metaphors currently available for Web development. We should begin an inquiry by examining the basis of the most common, popular, user-friendly, and productive web language, HTML, to see if it supplies the necessary logic constructs to implement the kinds of direct and indirect instructional designs we have described. HTML is the lingua franca of the web for the average designer. It is the tool most friendly to the average web page designer, and it is the tool taught to most beginning designers. It is designed specifically to allow page authors to prepare documents containing a range of resources and linkages once for interpretation and display on many properly configured computers. It allows designers to ignore differences in computer hardware, operating systems, display size, and local software preference settings. This alone is a spectacular achievement, especially appreciated by those who have worked in earlier environments where cross-platform compatibility was in most cases unobtainable. But much of HTML’s compatibility is a result of its membership in a larger group of markup languages (ML), all of which have similar cross-platform compatibilities. These markup languages are all descendants of a parent language called SGML (Standard Generalized Markup Language). Each markup language in the SGML family has the capacity for communicating a specific type of document, with its formatting, to a distant browser. The important point to be made is that markup languages derived from SGML are all based on the document metaphor, with a document, somewhat like a data base, having a certain standard structure (Leventhal, Lewis, & Fuchs, 1998). A markup language is simply a way of tagging the individual elements of a particular type of document (having a specific internal document structure) before sending the document’s elements for display. HTML documents have display elements such as “body,” “title,” and “list.” They also have reader-reactive elements such as form fields, click-sensitive graphic areas, and buttons. They also have relational links that permit the elements of the document to be accessed in various orders. But the range of structures and interactivity using this set of elements and resource types—as impressive as they are—is limited, especially when the processing of a learner response is taken into account. Moreover, markup languages are not sensitive to the context or meaning of a reader’s response, so a programmer has to supply it in the form of answer processing logic, which is not within the range of HTML user-friendliness. To handle these additional requirements, new tools like Java, and Perl are called into use and interfaced with HTML, and the user-friendliness and productivity of web authoring plummets. To escape some of the limitations of HTML, groups of users with specialized document types have created their own markup languages—derived from SGML and usually created in a tool language called XML—for the authoring, transmission, and display of documents that contain specialized structures. Mathematicians have constructed a Mathematical Markup Language (MathML). Its structures include formatting tags that allow the mathematician to specify to a browser how the individual elements are linked in terms of meaning (semantic or content tags) and how they are to be displayed. A sample of MathML is provided by Ion and Miner on their web page, Mathematical Markup Language: W3C Proposed Recommendation (www.w3.org/TR/PRmath/). The expression “x+a/b” can be tagged as: <mrow> <mi> x </mi> <mo> + </mo> <mrow> <mi> a </mi> <mo> / </mo> <mi> b </mi> </mrow> </mrow> The benefit of MathML is that equations that would otherwise be difficult to display in readable form come to the reader looking just like equations on a printed page, with spacing and placement of symbols just as they were intended by the author, regardless of the computer they are displayed on. Musicians have a Music Markup Language (MML). The benefits of Music ML are the same: musicians can send otherwise unreadable musical documents in a form that allows the receiver to read and interact with them. These and other markup languages, however, skirt the issue addressed in this chapter and do not deal with the implementation of highly interactive and sometimes adaptive instruction over the Web. The central question we must ask is whether the document metaphor and its implied logic constructs that lies at the base of the markup languages can be used as the base also for implementing the conceptual structures we have described—for both the direct and indirect instructional paradigms. We do not believe that the document metaphor alone can suffice, unless the definition of “document” as a data base of retrievable resources changes. The specialized markup languages are designed for the display of static document content. In contrast, the content of instruction, especially for indirect instruction which relies heavily on learner interaction with models and expert systems capable of making instructional decisions and exhibiting dynamic performance, is not easily contained within the boundaries of a collection of static, categorized structures that store and fit neatly within a data base. Indirect instruction often requires the construction of displays based on computed responses to learner actions. Tool Solutions How can tools be made easier to use, even when the forms of instruction created seem to be demanding more sophisticated logical structures and interactions between independent logical agents? What patterns of tool use and siting of logic processing will minimize traffic over the instructional web yet permit power, speed, flexibility, and individual learner attention in products? Some solutions present themselves that are within the immediate grasp of the designer while longer-term solutions continue to evolve: (1) the construction of reusable logic templates for direct instruction, (2) the construction of reusable components for indirect instruction, and (3) migration toward tools with more flexible and broadly applicable logic constructs for both types of instruction. Reusable templates for direct instruction. For many years, computer-based instruction developers have relied on template logic structures made of frames or handmade logic routines as an economy measure. Financial success for most CBI product companies is possible only by adopting a template approach. The economics of the Web will demand the same thing. Low-cost development will continue to be a requisite. Reusable templates are the most direct way to this goal for some types of instruction, especially the direct type. Reusable components for indirect instruction. Indirect instruction logics employ components that permit free play within an environment as well as system models and tools for use within a problem solving environment. Just as templates can be used to capture direct instruction logic for message delivery and practice interaction, reusable components can be manufactured that create environments, simulate cause-effect systems (models), and perform expert system functionalities. Many of these components can be created as empty logic shells that are provided with usable data at the time of use. Template components of this type have been used to create instruction for the training of aviators (Gibbons & Rogers, 1991a, 1991b; Gibbons, 1993), and for the training of library skills (Lacy & Gibbons, 1994; Wolcott, Gibbons, Lacy, & Sharp, 1994). These applications involve free-play environmental simulations followed by intelligent, real-time, performance-referenced feedback. These products involve the creation of independent, reusable components: a shell simulation engine, and a separate shell expert system for feedback. These efficient and compact instructional components are capable of generating instructional messaging from problem data files and live response records of the learner. Duffin and Gibbons (1997) and others (Gibbons, Duffin, Robertson, & Thompson, 1997) have also reported using object systems to create simple, parameterized, and switch-controllable expert systems capable of both coaching and feedback in either delayed or instantaneous mode. These expert systems operate on selectable comparison sources—either the expert’s or the learner’s own performance. These designs are well-suited to the web because of their parsimony. Migration to more flexible tools. Many designers find object-oriented development systems more economical and more flexible for building structures typical of indirect instruction. Not only can one-of-a-kind object suites be created, but templated object structures have been used to create efficient but instructionally effective object families (Gibbons & Thompson, 1997). Traditional authoring tool frames themselves can be created using object tools, suggesting that object systems represent a superset of tool constructs. In terms of web-focused object tools, Java appears to be preeminent, and authoring interfaces are emerging that provide non-programmers access to Java functionality. These facilitate designer creation both direct and indirect instructional products and allow a larger number of authors to access the power of the programming language. Object tools are uniquely suited for the construction of models of both natural and manufactured systems. The object-oriented approach to programming has its roots in creating simulations (Shasha & Lazere, 1995). However, simulation models alone do not constitute an instructional product. The experience of the model through problem solving normally requires support in the form of instructional augmentations (coaching, hinting, directing, explaining, giving feedback, etc.) that support the learner’s extraction of information from experience, construction of knowledge, and formation of performance patterns. These instructional augmentations often imply that two programs need to run simultaneously or in close coordination. The independence of these functionalities is essential for their portability and reuse. Conclusion We have tried to outline issues at the heart of web-based instructional design and production. We have invoked one old and one recent instructional paradigm to show the instructional implications for a medium hitherto purposed for information exchange. If the Web is to supply both direct and indirect instructional forms, new tools for web-based design and production must evolve. Several decades of experience that have already accumulated in computer-based instruction have shown that when the instructional constructs of a design correspond well with tool constructs provided by a specific tool being used, and when reusable logic patterns can be constructed and applied, the result is a product whose instructional plan is preserved intact and whose cost is reduced. However, when there is a mismatch between instructional and tool constructs, or when template logic cannot be used, instructional designs are compromised, or costs soar, and there are less frequently exportable and reusable elements of program code produced. The task of creating economical development tools that implement a new metaphor will be an especially difficult but critical challenge. Throughout the history of computer-based instruction, there has been a tendency for logic tool constructs to initially facilitate but later restrict the implementation of the designer’s strategic ideas due to the relatively rapid advance of theoretic ideas compared with the relatively slow advance of tools. Currently, conventional computer-based instruction faces these same challenges. The advent of the instructional Web will accelerate progress—hopefully in both webbased and stand-alone CBI. We therefore look forward with anticipation to the creation of the truly instructional web and more powerful CBI development tools than ever before. References Barrows, H. S. (1985). How to design a problem-based curriculum for the years. New York: Springer. Barrows, H. S. (1992). The tutorial process. Springfield, IL: Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the craft of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L. B. Resnick, (Ed.), Knowing, learning, and instruction: essays in honor of Robert Glaser. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Duffin, J. R. & Gibbons, A. S. (1997). Intelligent Interactive Math Testing Shells. Presented at the 9th Annual Summer Institute, Utah State University, Logan, Utah, August, 1997. Gibbons, A. S. (1993). New Tools for Creating Instruction and Simulations. Technical Paper No. 932600, Education, Training, and Human Engineering in Aerospace (SP-992), SAE International, Costa Mesa, CA. Gibbons, A. S. (1998). Model-Centered Instruction. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, April, San Diego. Gibbons, A. S. & Anderson, T. A. (1994). Model-centered instruction. Paper presented at the 6th Summer Institute on Automated Authoring of Computer-Based Instruction, Utah State University, Department of Instructional Technology, Logan, Utah. Gibbons, A. S., Duffin, J. R., Robertson, D. J., and Thompson, B. (1997). Instructional Feedback and Simulation: A Model-Centered Approach. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Northern Rocky Mountain Educational Research Association, Jackson, Wyoming, October, 1997. Gibbons, A. S. & Fairweather, P. G. (1998). Computer-based instruction: design and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications. Gibbons, A.S., & Rogers, D. H. (1991a). The maintenance evaluator: Feedback for extended simulation problems." Paper presented at the 9th Conference on Interactive Instruction Delivery. Society for Applied Learning Technology, Orlando, February, 1991. Gibbons, A. S., & Rogers, D. H. (1991b). Use of An Expert Critic to Improve Aviation Training. Paper presented at the Ohio State Symposium on Aviation Psychology. Sponsored by Ohio State University, Columbus, May, 1991. Gibbons, A.S., Thompson, B. (1997). Pseudosimulation: An example of low-cost authoring. Paper presented at the 9th Summer Institute on Automated Authoring of Computer-Based Instruction, Utah State University, Department of Instructional Technology, Logan, Utah. Hannafin, M. J., Hannafin, K. M., Land, S. M., & Oliver, K. (1997). Grounded practice and the design of constructivist learning environments. Educational technology research and development, 45(3), 101-117. Ion, P. & Miner, R. (Eds.)(undated). Mathematical Markup Language: W3C Proposed Recommendation. (www.w3.org/TR/PR-math/). Lacy, M., & Gibbons, A. (1994) The library location simulation at USU. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Educational Communications Technology—Region 8, Park City, Utah, May 1994. Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Lajoie, S. P. & Derry, S. J. (1993). Computers as cognitive tools. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Leventhal, M., Lewis, D., & Fuchs, M. (1998). Designing XML internet applications. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall PTR. Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: cognitive development in social context. New York: Oxford University Press. Shasha, D. & Lazere, C. (1995). Out of their minds: The lives and discoveries of 15 great computer scientists. New York: Copernicus/Springer-Verlag. White, B. Y. & Frederiksen, J. (1990). Causal model progressions as a model foundation for intelligent learning environments. Artificial intelligence. 24:99-157. Wolcott, L., Gibbons, A. S., Lacy, M., and Sharp, J. (1994) Navigating the information environment: An instructional simulation of information retrieval processes for university students. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Educational Communications Technology, Nashville, Tennessee, April, 1994.