Dialogues

advertisement

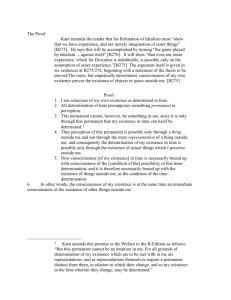

Hylas’s Last Objection The theory of immaterialism is inconsistent with the creation story of the Christian Bible. According to immaterialism, objects are just collections of ideas. And ideas cannot exist apart from being perceived by some mind. So to create a thing is just to create a collection of ideas in the mind of some spirit. But ideas cannot be created in God’s mind. (God is supposed to be eternal and unchanging, so that whatever “archetypal” ideas exist in God’s mind must be there eternally) So a creation of the world would have to be a creation of “ectypal” copies of God’s “archetypal” ideas in human minds. But according to the story, God created human beings last of all. According to immaterialism, and contrary to the creation story: Human beings must have been the first things to be created. The creation must be ongoing, involving the same activity now that it did at first (indeed, more in proportion to increases in the population) Berkeley’s Reply “All objects are eternally known by God, or, which is the same thing, have an eternal existence in His mind: but when things, before imperceptible to creatures, are, by a decree of God, made perceptible to them; then are they said to begin a relative existence, with respect to created minds.” Some other species of finite spirits (angels) existed prior to creation. God’s act of creation involved “decreeing” that different parts of the world (different collections of ideas eternally present in God’s mind) should gradually become perceptible to these spirits (that “ectypal” copies of God’s “archetypal” ideas should begin to be created in the minds of these spirits) A problem with this reply The reply implies that in order for a thing to exist, it is not sufficient that it be perceived by God. Because the existence of archetypal ideas in God’s mind is not supposed to suffice for the creation of things But then Berkeley cannot appeal to perception by God in order to explain what people really believe when they believe that objects exist in places where no finite spirit is around to perceive them. Nor can he present his theory as one on which God’s existence is necessitated by the belief in unperceived existence. A modified Berkeleian solution When we believe that vegetation exists in a desert where no finite spirit is present, what we really believe is that: i. God perceives the vegetation ii. God has “decreed” that, were any finite spirit present, then it would perceive the vegetation. Further problems Clause (i) is at best necessary, not sufficient for unperceived existence. It is the decree alone that suffices for the real existence of the thing. But this is tantamount to the counterfactual account of unperceived existence. Consequently: The common sense perspective is not preserved. Things do pop in and out of existence. The only sense in which they continue to exist unperceived is a hollow, counterfactual one: If someone were there, then they would get certain ideas of sense. What Berkeley Achieved He presented the classic version of an empirist theory of visual perception, showing that much of what we think we immediately or directly perceived is in fact due to early learning and unconscious inference. He worked out an anti-realist, instrumentalist philosophy of science according to which scientific theories do not tell us about the fundamental constituents of reality, but merely provide us with ways of calculating what sensory experiences we will have next. He offered a powerful critique of materialism and dualism, and a surprisingly coherent vision of an alternative picture of the world as consisting only of minds and ideas. His views shaped those of his most astute immediate successors (Thomas Reid, David Hume, Etienne Bonnot de Condillac, Immanuel Kant), whose work was developed in reaction to his own. In particular, he forced them to think more carefully about what a mind is, what an idea is, and what it means for a mind to perceive an idea.