Materiality/usage patterns - The Endocrine Society of Australia

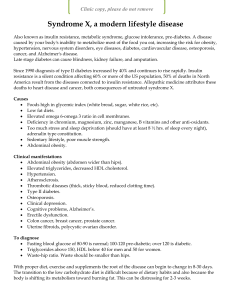

advertisement

1. Avoid routine multiple daily self-glucose monitoring in adults with stable type 2 diabetes on agents that do not cause hypoglycaemia Once target control is achieved and the results of self-monitoring become quite predictable, there is little gained in most individuals from repeatedly confirming. There are many exceptions, such as for acute illness, when new medications are added, when weight fluctuates significantly, when A1c targets drift off course and in individuals who need monitoring to maintain targets. Self-monitoring is beneficial as long as one is learning and adjusting therapy based on the result of the monitoring. Materiality/usage patterns Total utilisation of blood glucose test strips is growing at a rate of approximately 6.3% per annum. Approximately 35% of all blood glucose test strips dispensed are for people with type 2 diabetes not using insulin.1 In 2011-12, the Australian Government spent approximately $143.5 million subsidising glucose test strips for people living with diabetes, through both the PBS ($17 million) (Medicare Australia 2012) and the NDSS ($126.5 million). 2 Figure 1: Total Prescriptions (and NDSS equivalent supplies) for blood glucose test strips Source: Department of Health and Ageing 2012, ‘Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Products Used in the Treatment of Diabetes’, Report to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee Lessons from research and guidelines While self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) can improve glycaemic control, the clinically meaningful effects are negligible to small, particularly over the longer term. It is only recommended when there is appropriate education and willingness to self-adjust drug treatments based on readings. This makes the benefits of multiple daily tests even more questionable, particularly for those not using insulin. Paper Approach Conclusions Malanda et al 20123 Systematic reviews of RCTs, 12 included Farmer et al 20124 Meta-analysis based on individual participant data of RCTs published since 2000 with at least 80 participants Department of Health and Ageing and University of South Australia 20125 Literature review Clar et al 20106 Systematic review from 1996 to April 2009, 30 RCTs identified McIntosh et al 20107 Systematic review from January 1990 to March 2009 included RCTs and observational studies, 25 selected. International Diabetes Guidelines When diabetes duration is over one year, the overall effect of self-monitoring of blood glucose on glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes who are not using insulin is small up to six months after initiation and subsides after 12 months. Furthermore, based on a best-evidence synthesis, there is no evidence that SMBG affects patient satisfaction, general wellbeing or general healthrelated quality of life Not convincing for a clinically meaningful effect compared with management without self-monitoring, although the difference in HbA(1c) level between groups was statistically significant Studies and other recent evidence suggest that there is some initial benefit gained from blood glucose monitoring when a person is first diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. However, over time, that benefit is reduced as a person’s diabetes stabilises. Further, while regular testing may assist in identifying hyperglycaemia, regular engagement with healthcare professionals and periodic testing of a patient’s HbA1c is of greater benefit for patients not using insulin SMBG is of limited clinical effectiveness in improving glycaemic control in people with T2DM on oral agents, or diet alone, and is therefore unlikely to be cost-effective. SMBG may lead to improved glycaemic control only in the context of appropriate education and if patients are able to self-adjust drug treatment. Associated with a modest, statistically significant reduction in haemoglobin A1c concentrations, regardless of whether patients were provided with education. Did not demonstrate consistent benefits in terms of quality of life, patient satisfaction, prevention of hypoglycemia or long-term complications of diabetes, or reduction of mortality. SMBG should be used only Consistent with inclusion? Y Y Y Y Y Y Federation 20098 Allemann et al 20099 Systematic review and metaanalysis to 2009, 15 trials included. when individuals with diabetes (and/or their caregivers) and/or their healthcare providers have the knowledge, skills and willingness to incorporate SMBG monitoring and therapy adjustment into their diabetes care plan in order to attain agreed treatment goal SMBG compared with nonSMBG is associated with a significantly improved glycaemic control in noninsulin treated patients with type 2 diabetes. The added value of more frequent SMBG compared with less intensive SMBG remains uncertain N 2. Don’t routinely order a thyroid ultrasound in patients with abnormal thyroid function tests if there is no palpable abnormality of the thyroid gland Thyroid ultrasound is used to identify and characterize thyroid nodules, and is not part of the routine evaluation of abnormal thyroid function tests (over- or underactive thyroid function) unless the patient also has a palpably large goitre or a nodular thyroid. Incidentally discovered thyroid nodules on ultrasound are common. Overzealous use of ultrasound will frequently identify nodules, which are unrelated to the abnormal thyroid function, and may divert the clinical evaluation to assess the nodules, rather than the thyroid dysfunction, may lead to further unnecessary investigation, unwarranted patient anxiety and increased costs. Imaging may be needed in thyrotoxic patients; when needed, a radionuclide thyroid scan, not an ultrasound, is used to assess the aetiology of the thyrotoxicosis and the possibility of focal autonomy in a thyroid nodule or nodules. Materiality/usage patterns There is no specific MBS item for thyroid ultrasounds. Instead it is covered by the MBS items for neck ultrasounds. While not all neck ultrasounds ordered by endocrinologists will be thyroid scans (some will be assessing parathyroids), Figure 2 below shows the usage of neck ultrasounds ordered by all medical practitioners over the 2004 to 2014 financial year period while Figure 3 shows similar usage patterns just for endocrinologists over the shorter time period for which such specialised data is available over 2010 to 2014. Note that the data has not been separated out into data on the number of tests ordered as a first test by endocrinologists compared with those that need to be ordered as a follow up – which could better reveal the extent to which inappropriately ordered ‘first tests’ lead to additional follow up tests. We have requested customised data on this from the Department of Health but the data has not been received in time for the finalisation of this document. Bearing these caveats in mind, the figures show that there has been a significant increase in the number of neck ultrasounds ordered. For all tests over the 2004 to 2014 period the compounded growth rate has been 9.3% p.a. while the growth rate for the number of such tests ordered by endocrinologists has been more than 12.5% p.a. Total benefits paid out for these tests amounted to $9.8 million in 2004 but had grown to almost $28.3 million by 2014 which is an annual growth rate of more than 11%. This growth if anything may underestimate the opportunity costs from inappropriate testing as it does not include the costs for specialty consultations, subsequent surgery and other activity based on the initial inappropriate investigation. Nor have costs in terms of mental health burdens and anxieties caused by false positive results been taken into account. Figure 2: No. of services - MBS items 55032, 55033, 55011, 55013 Source: MBS website data Figure 3: No. of services ordered by endocrinologists - MBS items 55032, 55033, 55011, 55013 Source: MBS website data Lessons from research and guidelines There is insufficient evidence to evaluate the comparative benefit of a thyroid ultrasound for use beyond the boundaries of established indications, frequency, intensity, or dosage. Guidelines recommend that thyroid ultrasounds are useful in detection of nodules and cancer but not in the absence of any palpable abnormalities. There is also evidence that inappropriate thyroid investigations leads to the over detection and treatment of thyroid cancers including the lack of benefits from the use of RAIs for small papillary cancers. Paper Approach Conclusions Ahn et al 201410 Observational study Brito et al 201211 Clinical review Bahn et al 201112 Guidelines In 2011, the rate of thyroidcancer diagnoses in the Republic of Korea was 15 times that observed in 1993, yet thyroid-cancer mortality remains stable — a combination that suggests that the problem is overdiagnosis attributable to widespread thyroid-cancer screening. New imaging methods allow the detection and biopsy of thyroid nodules as small as 2 mm. There is an expanding gap between the incidence of thyroid cancer and stable death rates from papillary thyroid cancer which is evidence of overdiagnosis. Patients having thyroidectomy experience physical complications, financial and psychosocial burdens, and need lifelong thyroid replacement therapy. One caveat is that this inference about overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer is based on epidemiological and observational evidence. The use of thyroid ultrasonography in all patients with GD (Graves’ Disease) has been shown to identify more nodules and cancer than does palpation and 123I scintigraphy. However, since most of these cancers are papillary microcarcinomas with minimal clinical impact, further study is required before routine ultrasound (and therefore surgery) can be recommended’ Consistent with inclusion? Y Y Y 3. Don’t routinely measure 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D unless the patient has hypercalcemia or decreased kidney function Serum levels of 1,25-dihyroxyvitamin D have little or no relationship to vitamin D stores but rather are regulated primarily by parathyroid hormone levels, which in turn are regulated by calcium and/or vitamin D. In vitamin D deficiency, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels go up, not down. Unregulated production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D is an uncommon cause of hypercalcemia; this should be suspected if blood calcium levels are high and parathyroid hormone levels are low and confirmed by measurement of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. The enzyme that activates vitamin D is produced in the kidney, so blood levels of 1,25dihydroxyvitamin D are sometimes of interest in patients on dialysis or with end-stage kidney disease. There are few other circumstances, if any, where 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D testing would be helpful. Materiality/usage patterns As MBS restrictions have only recently (in October 2014) been introduced which break out a separate 1,25-dihyroxyvitamin D testing item, there is no useful dataset yet on long term usage patterns for this test item. Lessons from research and guidelines Guidelines recommend against using the serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (as opposed to the 25-hydroxyvitamin D) test for testing for vitamin D deficiency. The former test can be inaccurate because those with vitamin D deficiency can exhibit normal or even elevated levels of serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Paper Approach Conclusions Holick et al 201113 Guideline Holick et al 200714 Review article Recommends using the 25(OH)D] level to evaluate vitamin D status in patients who are at risk for vitamin D deficiency. Recommends against using 1,25(OH)2D assay for this purpose and are in favour of using it only in monitoring certain conditions, such as acquired and inherited disorders of vitamin D and phosphate metabolism. Serum 1,25(OH)2D does not reflect vitamin D reserves, and its measurement is not useful for monitoring the vitamin D status of patients. Serum 1,25(OH)2D is frequently either normal or even elevated in those with vitamin D deficiency, due to secondary hyperparathyroidism. Since the kidneys tightly regulate the production of 1,25dihydroxyvitamin Consistent with inclusion? Y Y D, serum levels do not rise in response to increased exposure to sunlight or increased intake of vitamin D.1-3 Furthermore, in a vitamin D– insufficient state, 1,25dihydroxyvitamin D levels are often normal or even elevated 4. Don’t order a total or free T3 level when assessing thyroxine dose in hypothyroid patients T4 is converted into T3 at the cellular level in virtually all organs. Intracellular T3 levels regulate pituitary secretion and blood levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), as well as the effects of thyroid hormone in multiple organs; a normal TSH indicates an adequate T4 dose. Conversion of T4 to T3 at the cellular level may not be reflected in the T3 level in the blood. Compared to patients with intact thyroid glands, patients taking T4 may have higher blood T4 and lower blood T3 levels. Thus the blood level of total or free T3 may be misleading (low normal or slightly low); in most patients a normal TSH indicates a correct dose of T4. Materiality/usage patterns Figure 5: No. of services - MBS item 66719 (2004 to 2014) Source: MBS website data MBS data (which does not include services provided to public patients in public hospitals or services that qualify for a benefit from the Department of Veterans' Affairs) shows an increase in the number of T3 level tests ordered over the 2004 to 2014 period. This has been at an average rate of 8.4% p.a. A breakdown is not available for the number of these tests ordered for hypothyroid patients. Nonetheless, the increase suggests there is a prima facie case for better selectivity in use of the ordering of these tests. In 2004 the total cost of these tests was more than $28 million. This had grown to almost $62.7 million in 2014 which is an annual average growth rate of around 8%. The variation in usage per capita is noticeable but not significant ranging from 5351 per 100,000 in NT to 10,685 per 100,000 in Queensland. Lessons from research and guidelines Guidelines states that the serum T3 measurement has limited utility in assessing hypothyroidism and can lead to both false positives and false negatives. Paper Approach Conclusions Garber et al 201215 Guidelines Serum T3 measurement, whether total or free, has limited utility in hypothyroidism because levels are often normal due to hyperstimulation of the remaining functioning thyroid tissue by elevated TSH and to up-regulation of type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase. Moreover, levels of T3 are low in the absence of thyroid disease in patients with severe illness because of reduced peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 and increased inactivation of thyroid hormone. Consistent with inclusion? Y 5. Don’t prescribe testosterone therapy unless there is evidence of proven testosterone deficiency Many of the symptoms attributed to male hypogonadism are commonly seen in normal male aging or in the presence of comorbid conditions. Testosterone therapy has the potential for serious side effects and represents a significant expense. It is therefore important to confirm the clinical suspicion of hypogonadism with biochemical testing. Current guidelines recommend the use of a total testosterone level obtained in the morning. A low level should be confirmed on a different day, again measuring the total testosterone. In some situations, for example conditions in which sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations are altered, a calculated free or bioavailable testosterone may be of additional value. Materiality/usage patterns Over two decades, total annual expenditure on testosterone products increased ninefold to $12.7 million according to PBS data and fivefold to $16.3 million according to IMS, a source of commercial pharmaceutical data. When adjusted for inflation and population growth, total annual expenditure on testosterone products increased 4.5-fold according to PBS data and 2.5-fold according to datafrom January 1992 to December 2010. Differences in total testosterone prescribed per capita between the states and territories with the highest and lowest rates of prescribing were roughly twofold at the beginning and at the end of this period.1 Figure 6: No. of scripts – testosterone products (2005 to 2011) Handelsman, D. 2012, ‘Pharmacoepidemiology of testosterone prescribing in Australia, 1992–2010’, Med J Aust 2012; 196 (10): 642-645. 1 Source: Australian Statistics on Medicines, various years, PBS PBS statistics show that there has been a steep increase in number of scripts written for testosterone products which increased by 5.23% p.a. between 2001 and 2011 (with the steeper increases starting from around 2005). The increase in injections and transdermal prescriptions has more than made up for declines in number of scripts written for other testosterone products. Lessons from research and guidelines Guidelines recommend that testosterone therapy should be considered in men who are androgen deficient. There is ongoing controversy over potential adverse effects associated with use of this therapy. Treatment should be preceded by consideration of the benefits versus risks in individuals. Research Paper Approach Conclusions Corona et al 201416 An up to date meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials involving 75 studies with 3,016 men treated with T and 2,448 with placebo for a mean duration of 34 weeks. Testosterone is not related to any increase in CV risk, even when composite or single adverse events were considered. In RCTs performed in subjects with metabolic derangements a protective effect of TS on CV risk was observed Finkle et al 201417 Cohort study of the risk of acute non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI) following an initial testosterone prescription (n = 55,593). Y Baillargeon et al 201418 Case-control study of men 66 years of age and older in which testosterone therapy was not associated with risk of myocardial infarction. Retrospective national cohort study of men with low testosterone levels who underwent coronary angiography (8709 participants) In older men, and in younger men with pre-existing heart disease, the risk of non-fatal MI was higher in the 90 days following prescription of testosterone compared with the preceding period.. In men at the highest risk, testosterone therapy was associated with lower incidence of MI Among a cohort of men who underwent coronary angiography and had a low serum testosterone level, the use of testosterone therapy was associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes. Testosterone therapy increased risk of a cardiovascular-related event. In trials not funded by the pharmaceutical industry the risk of a cardiovascularrelated event on testosterone therapy was greater than in pharmaceutical industry funded trials. Testosterone therapy was associated with reduced mortality, compared with no testosterone therapy ‘Our proposed diagnostic strategy reflects our preference to avoid labeling men with low testosterone Y Vigen et al 201319 Xu et al 201320 Systematic review and metaanalysis of placebocontrolled randomized trials of testosterone therapy among men lasting 12+ weeks reporting cardiovascular-related events.(27 trials included) Shores et al 201221 Cohort study in male US veterans with an initial low measured T concentration. Bhasin et al 201022 Clinical practice guideline Consistent with inclusion? N N Y N Y levels due to S HBG abnormalities, natural variations in testosterone levels, or transient disorders as requiring testosterone therapy. Our strategy also reflects our preference to avoid treatment in men without unequivocally low testosterone levels and symptoms in whom the benefits and risks of testosterone therapy remain unclear.’ ‘It is important to confirm low testosterone concentrations in men with an initial testosterone level in the mildly hypogonadal range, because 30% of such men may have a normal testosterone level on repeat measurement.’ The Task Force recommends against a general policy of offering testosterone therapy to all older men with low testosterone levels. (1 | +OOO) Fernández-Balsells et al 201023 Systematic review of studies from 2003 through August 2008, included 51 studies The Task Force suggests that clinicians consider offering testosterone therapy on an individualized basis to older men with low testosterone levels on more than one occasion and clinically significant symptoms of androgen deficiency, after explicit discussion of the uncertainty about the risks and benefits of testosterone therapy. Adverse effects of testosterone therapy include an increase in haemoglobin and haematocrit and a small decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. These findings are of unknown clinical significance. Current evidence about safety of testosterone treatment in men in terms of patientimportant outcomes is of low quality. Y 6. Don’t screen for gestational diabetes at 26-28 weeks using fasting plasma glucose, random blood glucose, glucose challenge test or urinalysis for glucose The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is currently the gold standard for the diagnosis of diabetes including gestational diabetes. If a woman has had gestational diabetes, a repeat OGTT is recommended at 6–8 weeks after delivery. If the results are normal, repeat testing is recommended between 1 and 3 years depending on the clinical circumstances. Caveats: This is likely to change with the pending Australasian Diabetes Society statement on HbA1c for diabetes diagnosis and the very poor compliance with OGTT ordering. New recommendations to screen for overt diabetes early in pregnancy for those at risk with a random or fasting glucose followed by an OGTT may challenge this. In addition, in the case of indigenous populations in remote areas, the random and fasting glucose tests may be the only practical and accessible alternatives to the OGTT. Thus limiting diagnosis to OGTT may limit diagnosis in these settings. Materiality/usage patterns Figure 7: No of services – MBS item 66545 (2004 to 2014) - Glucose challenge Source: MBS website data Figure 8: No of services – MBS item 66548 (2004 to 2014) - 75g oGTT Source: MBS website data Figure 7 shows the trend in number of services provided for only one of the glucose tests not recommended for gestational diabetes, namely the oral glucose challenge test (item 66545). By contrast the number of services provided for the oral glucose tolerance test which is recommended has grown significantly since 2004. This does not necessarily rule out consideration of this item on the shortlist though it does show that the use of inappropriate tests for gestational diabetes may be declining (and that correspondingly, use of the more appropriate test is increasing). Lessons from research and guidelines Guidelines recommend the oral glucose tolerance test over the glucose challenge test. Paper Approach Conclusions NICE24 Guidelines Offer early self-monitoring of blood glucose or a 2-hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) at 16–18 weeks to test for gestational diabetes if the woman has had gestational diabetes previously, followed by OGTT at 28 weeks if the first test is normal … Do not offer screening for gestational Consistent with inclusion? Y American Diabetes Association 201425 Guidelines diabetes using fasting plasma glucose, random blood glucose, glucose challenge test or urinalysis for glucose GDM screening can be accomplished with either of two strategies: 1. “One-step” 2-h 75-g OGTT or 2. “Two-step” approach with a 1-h 50-g (nonfasting) screen followed by a 3-h 100-g OGTT for those who screen positive Y 7. Avoid repeated measurement of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in patients with osteoporosis on stable Vitamin D supplementation Serum 25OH-D levels should not be retested once a desirable level has been reached through vitamin D supplementation unless risk factors change. Materiality/usage patterns Figure 9: No. of services - MBS item 66608 (2007 to 2014) Source: MBS website data MBS data (which does not include services provided to public patients in public hospitals or services that qualify for a benefit from the Department of Veterans' Affairs) shows a steep increase in the number of vitamin D tests ordered per year. However, the Department of Health does not link MBS data on these tests with their clinical purpose. Thus it is impossible to get a clear picture of the extent to which these tests are being used on those with osteoporosis but who already are on vitamin D supplementation. All that can be discerned is that there has been a steep increase in the number of vitamin D tests over time suggesting that the overordering of vitamin D tests is a ‘live’ issue and attempts to curb its use where unwarranted and introduce greater selectivity are to be welcomed. Lessons from research and guidelines Guidelines recommend against retesting of Serum 25OH-D levels once a desirable level has been reached through vitamin D supplementation unless risk factors change. It is also recommended that retesting should not take place before 3 months after administration of supplements. Paper Approach Conclusions Consistent with Royal College of Pathologists Australia 201326 Guidelines Nowson et al 201227 Guidelines Serum 25OH-D levels should be retested no earlier than 3 months following commencement of supplementation with vitamin D or change in dose. Once a desirable 25OH-D target level has been achieved, especially by the end of winter, no further testing is required unless risk factors change As it may take up to 2–5 months for serum levels of 25-OHD to plateau, retesting should not take place before 3 months’ inclusion? Y 8. Do not measure insulin concentration in the fasting state or during an oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin sensitivity Measurement of insulin either in the fasting state or during an oral glucose tolerance test is not a clinically useful method (and may be costly because of the insulin assay) to estimate insulin sensitivity. The hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic (HIEG) clamp is the gold standard for assessing insulin sensitivity as it is possible to assess tissue specific sensitivity and can be used in all types of populations. This feature is important because a method of standardisation must be developed to control for various factors prior to any methods for measurement. Materiality/usage patterns MBS data on the number of serum insulin tests is not available as the relevant MBS item number for this (66695) bundles together a number of blood assays. Data on usage of the OGTT is available but not sufficiently fine grained to measure incidence of usage for the purpose of assessing insulin sensitivity. Lessons from research and guidelines Guidelines state that the HIEG clamp is the gold standard for assessing insulin sensitivity while OGTT indices are not as precise. Guidelines also particularly recommend against the measurement of serum insulin levels as a method of assessing for risk of DM2 as part of the assessment of PCOS. Paper Approach Conclusions Antuna-Puente et al 201128 Clinical review Teede et al 201129 Clinical guideline Borai et al 201130 Clinical review Samaras et al 200631 Clinical review The HIEG clamp is the gold standard for assessing insulin sensitivity. OGTT indices are not as precise as the HIEG. Previous studies have noted that fasting blood glucose level alone appears to lack sensitivity in screening for prediabetes or DM2 in PCOS, with national and international groups recommending screening all women with PCOS with an OGTT It is important to note that assessment of IR or measurement of serum insulin levels has no current role in clinically assessing for risk of DM2. Where possible the HEC (hyperinsulinaemic euglycaemic clamp), as the most accurate technique available, remains the first choice but simpler and inexpensive methods may be appropriate provided the investigator is aware of their limitations. Serum insulin levels are poor measures of insulin resistance. Furthermore, Consistent with inclusion? Y Y Y Y there is no clinical benefit in measuring insulin resistance in clinical practice. Measurements of fasting serum insulin levels should be reserved for large population-based epidemiological studies, where they can provide valuable data on the relationship of insulin sensitivity to risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease References: Department of Health and Ageing 2012, ‘Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Products Used in the Treatment of Diabetes’, Report to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. 2 Department of Health and Ageing 2012, ‘Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Products Used in the Treatment of Diabetes’, Report to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee. 3 Malanda et al, Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 1. 1 Farmer et al, ‘Meta-analysis of individual patient data in randomised trials of self monitoring of blood glucose in people with non-insulin treated type 2 diabetes’, BMJ. 2012 Feb 27;344:e486. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e486. 5 Department of Health and Ageing and University of South Australia 2012, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Products Used in the Treatment of Diabetes, Part 1: Blood Glucose Test Strips. 6 Clar et al,’ Self-monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: systematic review’, Health Technol Assess. 2010 Mar;14(12):1-140. doi: 10.3310/hta14120. 7 Mcintosh et al 2010, ‘Efficacy of self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus managed without insulin: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Open Med. 2010;4(2):e102-13. Epub 2010 May 18. 8 International Diabetes Federation 2009, Guideline: Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose in Non-Insulin Treated Type 2 Diabetes. 9 Allemann et al, ‘Self-monitoring of blood glucose in non-insulin treated patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Curr Med Res Opin. 2009 Dec;25(12):2903-13. doi: 10.1185/03007990903364665. 10 Ahn et al, Korea's Thyroid-Cancer “Epidemic” — Screening and Overdiagnosis, New England Journal of Medicine 2014; 371:1765-1767. 11 Brito et al, Thyroid cancer: zealous imaging has increased detection and treatment of low risk tumours, BMJ 2013; 347 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4706 12 Bahn et al, Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid. 2011;21:593-646 13 Holick et al, Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jul;96(7):1911–30. 14 Holick, ‘Vitamin D deficiency’, N Engl J Med 2007;357:266-81. 15 Garber et al, Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Endocr Pract. 2012; Sep 11:1–207 16 Corona G et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with testosterone-boosting medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2014; 13: 1327-1351 17 Finkle et al, Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men, PLoS One. 2014 Jan 29;9(1):e85805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085805. eCollection 2014. 18 Baillargeon et al, Risk of myocardial infarction in older men receiving testosterone therapy. Ann Pharmacother 2014; 48: 1138-1144 19 Vigen et al, Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels, JAMA. 2013 Nov 6;310(17):1829-36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280386 20 Xu et al, ‘Testosterone therapy and cardiovascular events among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials’, BMC Med. 2013 Apr 18;11:108. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-108. 21 Shores et al, Testosterone treatment and mortality in men with low testosterone levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: 2050-2058 22 Bhasin et al, Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 95: 2536-2559 4 23 Fernández-Balsells et al, Clinical review 1: Adverse effects of testosterone therapy in adult men: a systematic review and meta-analysis, J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Jun;95(6):2560-75. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2575. 24 NICE Pathways, ‘Screening and diagnosis of gestational diabetes 25 American Diabetes Association, Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2014, Diabetes Care Volume 37, Supplement 1, January 2014. 26 Royal College of Pathologists Australia Position Statement - Use and Interpretation of Vitamin D testing, May 2013 27 Nowson et al, ‘Vitamin D and health in adults in Australia and New Zealand: a position statement’, Med J Aust 2012; 196 (11): 686-687 28 Antuna-Puente et al, How can we measure insulin sensitivity/resistance?, Diabetes Metab. 2011 Jun;37(3):179-88. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2011.01.002. Epub 2011 Mar 23. 29 Teece et al 2011, ‘Assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome’, MJA 195 (6) · 19 September 2011. 30 Borai et al, Selection of the appropriate method for the assessment of insulin resistance, BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011; 11: 158. 31 Samaras et al, Insulin levels in insulin resistance: phantom of the metabolic opera?, Med J Aust. 2006 Aug 7;185(3):159-61.