Print Request: Current Document: 6 Time Of Request: Friday

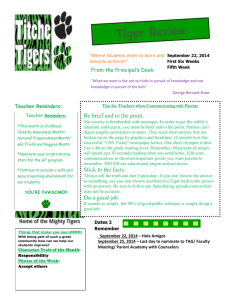

advertisement