Ethics, International Law and Human Rights

advertisement

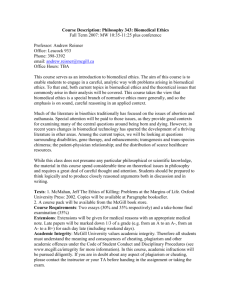

Ethics, International Law and Human Rights Featuring Dr. Pat Kuszler, Dr. Bruce Kochis, and Ms. Diane Atkinson-Sanford Dr. Patrica Kessler Mixing of law and health, and health related human rights with a focus on ethics. “How can we translate” many of the concepts we have developed in the field of health standards into the international community—the answer is via ethics and human rights. Specifically focusing on Bio-medical ethical (BME) concepts. The underpinning of biomedical ethics was brought out of the same era (post WWII) as human rights and they are tied. Example: Nuremberg trials and human experimentations began the debate that human medical status should be protected in terms of personal and cultural rights. BME has been an evolving concept and is now entering into a level of scholarship and has become part of the background of society. BME fell out of importance in the 195060’s. A rude reawakening occurred in the 1970’s after the Tuskegee project. The concepts were then tied into the common medical practice. The idea evolved that a person could not be a means to an end, and ethics must focus on the idea of community. It’s important to relate concepts of justice and benevolence to the medical field. Distributive and compensatory justice, in relation to health, is a human right. Many have argued that BME and therefore human rights must be globalized because they are dealing with global issues. How can we incorporate BME into the concept of human rights? A difficult point is that human rights is focused on the individual and must be transitioned to the community based need of health care distribution. Perhaps law can bridge this gap. Ms. Diane Atkinson-Sanford Goal is to tie in the international law side of the human rights-medical provision issue. Look at the levels of interventions and how health officials can make use of it. International health is a horizontal system. For example all countries must approve of the rights/law before it is enacted. Also a treaty not recognized by a country that does not approve with the treaty. Because international law is developed as a “bargaining evolution of theory” it often results in a simplified version of what was intended. Because the right to health is established, does it mean a right to health care? And if so at what level. Also because all other human rights are based on that idea, it has become toothless. It has evolved and is something that is progressively realized, ie always allowing the country to escape any real pressure. Enforcement often occurs on a vertical level, and in a micro-approach, which is very difficult with international law. Prevention is of better international law structure. 1. Prevent a specific action from occurring by injunction. 2. Using a human rights impact assessment (HRIA) 3. Ascertain what rights could be infringed upon by a countries action Example of reproductive health with adolescences in institutions, TB treatment depends on housing issues, economic issues etc Reporting: With multiple organizations and countries trying to assess the samesituation in a particular place, though troubled by difficulties, has the benefit of bringing attention towards a situation. Some international and regional organizations (UN etc) are involved in field work. Enforcement Requires an understanding of the law. Must understand what the underlying right to a problem might be, and enforce the problems resolution utilizing this right. Can use other routes of enforcement such as environmental law, or right to shelter etc. International Tribunals are formed with the concept of limited power between the countries. So international reaction is with political embarrassment or other avenues such as resources or deportation law. Dr. Bruce Kochis Speaking in general of human rights “regime.” Work of health provision requires you to become “public intellectual’s” ie health workers must understand policy and theoretical models and how they respond to actual issues in the field. Many distinct issues that effect specific locations. Items that effect Health provision Rights Inducements Rules Economics And Human Rights Historically Human rights began out of the disruption of World War II, and has a revolutionary quality about it. It has only evolved for fifty years and though it has grown rapidly it is not as developed as well as other structures. Development of Human Rights Standard setting 1 Treates conventions and laws protecting various levels of human rights. Forged out of many interests that are complex and allow many interpretations. Over 140 tools for declaring human rights that can be used by health care officials. 2 Investigation and Reporting Countries, NGO’s etc 3 Enforcement International tribunals, investigation etc. Least developed but is playing an increasing role. Three types of rights from cold war - bickering 1 Civil and Political rights 2 Economic social and cultural rights (right to health) 3 Solidarity rights- those things produced by the world for the people, peace, knowledge, technology Because human rights are a historical phenomena they are not inevitable. They are and will continue to evolve. Because it is always critical of the current order, it is always a destabilizing force and will remain unstable itself. Questions: Can you elaborate on State Department country human rights reports loosing their creditability? Kochis The reports began as political spin and but under the Carter administration became accurate. They have since served as a resource to gauge the level of human rights in all countries of the world except the US, with significant credibility. Recently they have begun to become increasingly political following the agenda of the US government. Do human rights organizations and health NGO’s work together and can one do both? Sanford Yes they do, but perhaps not enough. Some larger organizations are embracing the idea of partnership. There are many opportunities for work in this field, approach the orgs, take classes and get a law degree. With the changing political climate of human rights it will become increasingly important that these ideas overlap. Kochis Some situations require health professionals to be pulled into the legal field when they are the ones that uncover the problems. This will complicate your life and can put you in situations that you may not be prepared for. Can you talk about the ethics of economic sanctions and are these a case of violations of human rights? Kochis: Sanctions can be used as a tool for influencing human rights abuses. Example South Africa, human rights abuses were influenced by sanctions. Kuszler: It is not a simple system. Trying to improve human rights and health while enduring sanctions introduces a dynamic that’s more volatile, which is worse. Biomedical ethics and human rights are not individualized – rather, they are applicable to all. Both law and medicine involve daily action with concomitant risk. This is also true on a larger scale with external facilitation of human rights enforcement. Finding a balance is a challenge for political leaders & human rights professionals. Kochis: In 1994, Senator Tom Harkin introduced an act to congress to ban the import of goods to the US which were manufactured with child labor. This was well-intentioned; however, it resulted in the firing of 50,000 children from sewing factories in Bangladesh. These children then went into prostitution, mining, leatherwork – the most dangerous work – because they still needed to support themselves and their families, but couldn’t remain at the factories. Public policy is a complicated process. Learning about social science will help you grasp the implications of policies. A helpful book is “The Power of Human Rights” by Risse et al. In short, sanctions have beneficial as well as negative externalities. The impact can be both good and bad; anticipating that is difficult. What are the implications of patent law? Kusler: There has been a great deal of press coverage recently on drug patents and how they intersect with the pharmaceutical needs of developing countries. There are multiple frameworks to view this through. The original purpose of drug patents was to disseminate products in a market and not allow them to be exploited by the original developer. The large research and development costs shouldered by the production companies, combined with a capitalist system, means the companies want to make both cost and some profit through the revenue for their products. Hence, we have expenisive drugs on the market, protected by those patents. The exclusivity comes from the patent licensing fee. How can a country circumvent this exclusivity and high cost? There is tremendous regulation of drug costs in some countries, which shifts the costs to other countries that aren’t regulated, like the US. Unfortunately, often developing nations can’t even afford to buy needed pharmaceuticals at cost. How can we provide the people of developing nations with the drugs and medical devices that they need? Eliminating patents is not the answer. Doing this wouldn’t guarantee equity of distribution. The real root of the problem is that most countries are unresponsive to this quandary; it’s not just the patent system and the pharmaceutical companies. Is the model of US biomedical ethics a good example for other countries? Kuszler: One way to inculcate biomedical ethics ideals is through including them in the medical practices of developing countries. For example, neither informed consent nor involving the general population in decisions regarding societal health care are common in other countries. How would other countries adapt US ideas to fit their own culture? How can we encourage respect for the individual? If we want to achieve the maximum benefit, we need to take the maximum risk. The easiest, first step is to instill a heightened sense of obligation to provide equal access to health care in the US. Kochis: A non-governmental organization (NGO) in Senegal felt compelled to respond to female genital cutting. They didn’t simply say that it’s wrong. Instead, they did educational modules on health and human rights by teaching in villages. They would return every few to teach about various topics, and then cycle through again. Over the course of many years, local people made connections between the health education & human rights, they’d subsume it on their own under their own cultural systems. They changed their practices on their own and discontinued the female genital cutting. This took many years to implement. The education offered a human rights strategy that could be taken over by people in their own context. A law was eventually passed forbidding the cutting, after the people decided. The NGO believes that cultural change has to be village up (instead of laws coming down from the government) to really convince people. Which is more effective – the imposition of ideas or the infiltration of ideas? Another example is the issue of obtaining informed consent from someone without germ theory. Education and promulgating ideas is a slow process but an effective one. It’s being used in other areas. It encourages us to think about many ways of arriving at goal Kuszler: The previous story is similar to ones in the US. In some examples, enacting a law before obtaining public support is not the best method. When she taught in a Slovenian medical school, she learned that reproductive procedures are seen as a medical right, despite a population that is 80% catholic. The government has no role in this. A substantive and stable set of rights can be found through the appropriate path. Atkinson-Sanford: The negotiating process of law can restrain you in conversation and implementation regarding biomedical ethics. The interntional health community disregards informed consent. Health profession students find opportunities to consider any adverse impact of compromising biomedical ethics on human rights. How can I prepare to do human rights work? Kochis: If you’re interested in doing human rights work, there are many opportunities in organizations. There are about 80,000 NGO’s to work with. He suggests that you get involved in local communities. In order to be sensitive to and knowledgeable about those communities, LISTEN to people, ask about their situations, respect their perspective. In short, there are too many examples of Ugly Americans imposing rather than learning. Also, Kochis suggests that you become aware of the historic and current evolution of human rights, be well versed in the pertinent issues, and educate yourself about the language and current topics. A useful new journal is called Health and Human Rights. Kuszler: To do human rights work, prepare as assiduously as possible – be culturally aware, read, and talk to predecessors to learn as much as you can. Atkinson-Sanford: The Peace Corps recommends that you spend 1-1.5 years deciding how to implement your project in a new region. Ths means taking the time to know the people, build trust, formulate appropriate policy, establish communication, and figure out what’s appropriate and sensitive and will be received well. Examples were offered in an African village and a Bosnian town. Kochis: Do some reading about implementation – it’s often ignored. The issue of implementation is a different part of policy – it requires patience, understanding, and dedication. The theoretical models that can be quite exciting can also be short-sighted. NGO’s and governments need people who study policy because policy students are often trained in both implementation and subsequent evaluation. Atkinson-Sanford: In the globalization of biomedical ethics, it’s important that the rights of the individual are not forgotten. Weigh grave immediate risk as well as personal worth. The current Bush administration seems less interested in Human Rights, which raises the question: does administration change disrupt human rights work? Kochis: Perhaps – but it creates job security for the academic. Seriously, continuity is important. The US has good record and credibility, in part because Jimmy Carter made human rights a priority. For the US to not be involved with the new international criminal court and to not contribute to agreements makes us look uncooperative. It was really grim in 1981 with Reagan’s election but that administration couldn’t eliminate human rights as a priority because the human rights movement too strong. Also the core group of human rights workers get caught up in anti-globalization, which is not a well thought out movement, and detracts from human rights work. A new organization is currently being established which will try to offer a greater depth of understanding. Atkinson-Sanford: In her experience, it’s not always the regime of a country that affects international human rights. Sometimes it’s constituent based support. If human rights workers can find ways of communication it will be possible to be successful. A regime is more of a challenge than an end to one thing. Kuszler: There is a core level of support for human rights work in the US. However, any change in the US government can have a destabilizing or supporting effect. Many times the effect depends on the issue and on what stance is taken on it by the regime and by the core supporters.