Field Statement - English 613

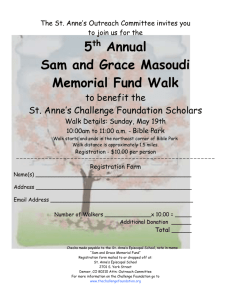

advertisement

Gared Alemtsahai Gared English 608: Intro to Critical & Research Methods December 16, 2010 “I believe in a true analogy between our bodily frames and our mental; and that as our bodies are the strongest, so are our feelings; capable of bearing most rough usage, and riding out the heaviest weather.” (Austen 155) – Captain Harville, Persuasion “Anne Elliot: Her Bloom, Body, and Physical Contact with Wentworth” Scholars have critiqued Jane Austen’s works for decades. One of the earliest critical texts, Jane Austen and Her Art, written by Mary Lascelles, was published in 1939, and then republished in 1995. Brian Southam, the writer of the foreword in Lascelles’s book, praised her because: “…since the publication of Jane Austen and Her Art, there has come an overwhelming body of critical writing about Jane Austen…this classic study…analysis of Jane Austen’s style and narrative art and the experience of life and literature” (Lascelles vi), changed the way critics critiqued Jane Austen. Many critical scholars of Jane Austen usually refer to Lascelles because Lascelles focused on Austen’s style, and narration, as opposed to solely writing her biography. Judy van Sickle Johnson, author of “The Bodily Frame: Learning Romance in Persuasion,” states in her article, “Mary Lascelles has noted that in Persuasion Austen uses the term ‘romantic’ in a new way: ‘…it is the first time that Jane Austen has used this adjective sympathetically’ ” (Johnson 44). In the subsequent decades after the publication of Lascelles text there seemed to be less critique of Jane Austen than recent decades. In the fifties, sixties, and seventies there was a few scholarly texts published about Jane Austen. Most of the chapter titles 1 Gared are the novel titles, and the chapters essentially fulfill what it sets out to do, which is discussing the novel in its entirety by incorporating long summaries. Some are like book reviews. Also, the chapters are not as long as the chapters written during and after the eighties. In the eighties there was a vast number of scholars writing about Jane Austen’s novels. There was a: “…shifting attention to previously unexamined issues, providing new terms for the critical lexicon, and reopening questions foreclosed or effectively abandoned by the reigning consensus” (Richardson 142). During the eighties scholars began writing critically about the novels instead of summarizing. It seems that scholars were finding ways to re-examine her novels by making connections to advances in science, sociology, psychology, and medicine. Also, they were “reopening questions” that were not considered before, or “abandoned”. It seems as if that initiative continued into the nineties, and the focus of the articles / chapters became less broad. Scholars would discuss a few related themes, and examine their relationships in the context of the novel, as opposed to touching on all themes. The texts and articles written in the present usually focus on one theme, or two, and the author critically examine that aspect of the novel. The above-mentioned quote, spoken by Captain Harville in Persuasion, mentions the key themes in the novel: “the bodily frame,” the “mental,” and the “feelings”. In my footsteps essay I introduced the initial article I worked with, Alan Richardson’s “Of Heartache and Head Injury: Reading Minds in Persuasion, which focused on the psychological aspects of the novel. The psyche, body, and emotions are very important in the novel, so most scholars focus on these themes that are so intertwined. The 2 Gared “romance” between Anne and Captain Wentworth is unlike all of the other “romances” in Austen’s other novels. The lack of dialogue between the heroine and Captain Wentworth, combined with Austen’s elaboration of the bodily sensations and physical contact between the two, is what makes this novel unique. As John Wiltshire, author of Jane Austen and the Body, states: “Persuasion is a novel of trauma: of broken bones, broken heads and broken hearts” (Wiltshire 165), which corresponds neatly with Captain Harville’s “the bodily frame,” the “mental,” and the “feelings”. Since I have already discussed the psychological aspect in my footstep’s essay, I plan on examining Anne’s bodily frame, her bloom and rebloom, and the scenes of: “…this new excitement of physical contact, this arousing consciousness of growing intimacy” (Johnson 44), between Anne and Captain Wentworth. The scholars that I feel are in conversation with each other by discussing the bloom and rebloom theme, the “body,” and exploring the bodily frame through physical contact, are: Judy van Sickle Johnson, Mary Ann O’Farrell, author of Telling Complexions: The Nineteenth-Century English Novel and the Blush, Amy M. King, author of Bloom: The Botanical Vernacular in the English Novel, Kay Young, writer of the article, “Feeling Embodied: Consciousness, Persuasion, and Jane Austen,” and John Wiltshire. Johnson elaborates on the “bodily frame” and how it affects the “romance” between Anne and Wentworth. O’Farrell’s argument surrounds the idea of “mortification” and how it affects Anne inwardly and outwardly. King interestingly utilizes Carl Linnaeus’s, “ ‘sexual system’ of plant classification” (King 3) to explain Anne’s bloom and rebloom, and how it effects her eligibility as a “marriageable girl”. Young delves into the “body/consciousness” and the “embodied language of feeling”. 3 Gared Wiltshire discusses the “nurse” role that Anne is placed in most situations in the novel, and how Wentworth occasionally becomes her “nurse” in times when Anne is distressed. All of these texts present different perspectives about the bloom plot and the physicality in the novel. All of the mentioned scholars found different ways of interpreting this unique and “romantic” novel. In the beginning of the novel Anne is a twenty-seven-year-old whose status as a “nobody with either father or sister: her word had no weight…she was only Anne” (Austen 5), makes her seem unappealing as a heroine. O’Farrell describes Anne’s: “…complex and perverse relation to mortification…inheres in her desire to exploit its capacity to refine and to render insensible. ‘Nobody’ to her father and sister, or at best ‘only Anne,’ she has had to accustom herself to mortification” (O’Farrell 30). O’Farrell argues Anne is constantly degraded by her family and she attempts to ignore this “mortification” by being “insensible” of it, despite Lady Russell’s pleas that Anne deserves to be acknowledged as an equal member in their family. Also, Anne “accustoms” herself to “mortification” and she wisely refrains from interfering, unless absolutely necessary, in the affairs of her foolish father and sister. Wiltshire similarly argues: “Anne Elliot is a woman oppressed and insignificant, a ‘nobody,’ discouraged by a burden of grief and regret that she has borne alone…” (Wiltshire155). According to Wiltshire, Anne is “oppressed” by her family; an “insignificant” woman placed in what Richardson terms the “Cinderella plot”. Wiltshire also mentions her grief over rejecting Wentworth and the “oppression” of that “burden” she has to carry “alone,” without any family support. She was persuaded to reject Wentworth and then she was left “alone” to tackle her “grief and regret”. Anne is 4 Gared “discouraged,” by her surroundings and situation, unable and unwilling to assert her, which makes her seems like a “nobody”. She is almost quite passionless by her “grief” until Wentworth returns, and then she is transformed from a “nobody” into a passionate woman through the revival of her bodily sensations. Kay Young discusses Anne’s place in the family circle as a “nobody”. She intricately scrutinizes Anne’s body and consciousness by literally separating the word: “To be ‘nobody’ …means to have ‘no body’. Anne with ‘no weight,’ as disembodied to them, erases Anne as a mental image for her remaining family. She has no words…so she gives way because she has no other way to be with them. To be ‘only Anne’ means for Anne not to be to them…not held in her family’s consciousness” (Young 82-3). Young suggests Anne as a non-existent being to her family, a person with “no body” in the “family consciousness”. Anne also “gives way” by not standing up for herself and she does not know how “to be” with them. Young uses the phrase “to be,” similar to Hamlet’s use of the phrase in his soliloquy, which demonstrates the family’s disregard of Anne as a “body” worthy of respect. Her father, Sir Walter, does not respect her because of her “bloomless body” and her sister considers her “insignificant” because Anne is not as conceited as their “blooming” selves. Anne’s bloom is connected to her physical appeal and the “early loss of bloom and spirits” (Austen 20), causes Captain Wentworth to believe Anne “so altered” (Austen 41). Wiltshire mentions Anne’s “prematurely aging body and face” (Wiltshire 155), while King goes more in depth about the “alteration” Wentworth sees: “The insistence in the narrative about Anne’s bloom signals that bloom is no mere description… That bloom refers primarily to the marriageable girl…Wentworth improves physically while 5 Gared Anne Elliot declines, a difference the novel employs to assert the relative importance of courtship to female destiny” (King 127). King claims that Anne cannot fulfill her destiny as Wentworth’s wife if she’s not in bloom. Without her bloom she is not eligible as a “marriageable girl”. O’Farrell builds off of King’s claims by describing the: “…hurt…by what she seems to learn here about her personal appearance. Hurt to think she has become unattractive, Anne imagines that Wentworth, when in her presence, looks at her only to trace in her face the ‘ruins’ of what he had once found pleasing” (O’Farrell 34-5). Although she’s not in bloom, she has emotions; her emotions start to become more overpowering as the novel progresses. O’Farrell brings up this concept of attraction: does Anne even consider personal appearance before Wentworth mentions it? Anne seems insensitive about her “unattractive” state until he comments on her looks, which “hurts” her feelings. She starts to become more perceptive of her “bodily frame” through her emotions. Young contrasts the difference between being “in bloom” and desirable, and being “faded” and ignored. To elucidate her point she uses the colors red and white to demonstrate the difference in bloom: “Having ‘bloom’ makes a woman visible (because marked in red as desirable, admirable, sexual) and being ‘faded’ makes her invisible (because marked in white as bloodless, sexually erased)…she needs figuratively to feel seen ‘in bloom’ to feel conscious of her sexuality, beauty, and embodiment as a woman of twenty-seven” (Young 83). Anne’s bloom is important for her inwardly and outwardly. Without “bloom” Anne is “invisible” and “sexually erased,” which is difficult for “a woman of twenty-seven” to deal with. She already has to live with the regret of rejecting Captain Wentworth, and the “consciousness” of her own loss of bloom, while 6 Gared he “improves physically” and condescendingly looks at her “ruined” face. Despite Captain Wentworth’s sneer at her “alteration,” he behaves most gallantly towards her when she requires the most assistance. Most of the scholars I researched discuss scenes where Anne and Wentworth experience physical contact. These scenes are important because: “The renewed courtship between Fredrick Wentworth and Anne Elliot is remarkably, almost dangerously nonverbal. The man and woman say very little to each other, but much is felt, physically as well as emotionally” (Johnson 46). Since their “renewed” relationship is “dangerously nonverbal,” these scenes give us a glimpse into their heart through their emotions, despite the interferences of reason and denial. Also, “much is felt, physically,” through body contact, and “emotionally through “renewed” feelings. Wiltshire uses a quote from Johnson to elaborate on the “physically” and “emotionally” relationship between Anne and Captain Wentworth: “It’s power, as she [Johnson] describes it, ‘resides in Austen’s success in sustaining the credibility of a renewed emotional attachment through physical signs. Although they are seemingly distant, Anne and Wentworth become increasingly more intimate through seductive halfglances, conscious gazes and slight body contact’ ” (Wiltshire 190). The “slight body contact” greatly assists their “nonverbal courtship”. The “intimacy” between them increases as they meet more often, which provides ample opportunities for “seductive half-glances” and “conscious gazes”. Their “distance” decreases as they slowly acknowledge they still love each other. The first scene of bodily contact is when Anne is kneeling and tending to her nephew who dislocated his shoulder. Captain Wentworth walks into the room and is 7 Gared startled that he is almost alone with Anne. Charles Hayter, the cousin of Anne’s brotherin-law, comes into the room followed by her other two-year-old nephew, who climbs on her back and clings to her neck in a way that it’s difficult to get him off. She tries to get him down, but to no avail (Austen 54). Wentworth goes to her silently and frees her of the child, and: “…Wentworth relieves Anne’s body through the agency of his physical contact with the body of the child...The rescue leaves Anne quite speechless, overwhelmed with confused emotions” (Wiltshire 173). Shortly after the others arrive and Anne leaves the room to compose herself. It would seem appropriate for Hayter to “rescue” Anne, instead of Captain Wentworth. Wentworth “rescues” her instinctively when he feels she is in discomfort. Wiltshire places Wentworth in the “nurse role,” and Anne as the distressed patient (Wiltshire 172). Throughout the novel Anne nurses and helps everyone, without receiving any help from anyone, except Wentworth, who is receptive of her discomfort (Young 85). His gallantry overwhelms Anne and leaves her “quite speechless”. She would have never expected such an act of kindness from Wentworth! It gives him creditability as an honorable man, although Anne has grievously wronged him. King draws our attention to the concept of “physical awareness” of Anne and Wentworth that is introduced through this child. King claims that “Wentworth’s touch” is what causes Anne’s “disordered feelings” and “painful agitation” that leaves her puzzled by the experience (King 129). In her helpless condition, kneeling before one child and then being harassed by the other demonstrates Wentworth’s vulnerability towards her suffering; he cannot ignore her when he perceives she is in pain (Young 85). Anne has not been near, or touched by Wentworth for years, so this little act of kindness 8 Gared brings “passionate warmth” and the hope of “romantic possibility” (Johnson 53). It also awakens her ill-suppressed feelings towards him. She cannot walk away from this experience without feeling the stirrings of love that she believed were extinguished long ago. The second scene of bodily contact is when Anne and Captain Wentworth are apart of a group of women and men walking outdoors in the country. After walking for most of the morning, Anne becomes tired and Wentworth notices her fatigue. Coincidently, his sister and her husband come alongside the group in their gig and offer any of the women a ride. They politely decline and when they are ready to leave Wentworth whispers to his sister to offer Anne a ride. Before she could object: “She was in the carriage, and felt that he had placed her there, that his will and hands had done it, that she owed it to his perception of her fatigue, and his resolution to give her rest” (Austen 61). Wentworth’s relieves her pain because he shares in her pain (Young 85). Wentworth is “physically aware” of Anne and her pain. King debates whether or not he actually touches her by placing her in the carriage because of the ambiguous statement “felt that he had placed,” which is open to interpretation (King 129). Young suggests that Wentworth’s touch makes Anne conscious of her body and “emotional aliveness” (Young 86). Johnson also feels that way, and the experience enables them to have an: “…an exquisite moment of physical contact, however, evokes even greater pleasure, a sharper sense of mutual warmth and attraction…” (Johnson 54). This “pleasure” Anne feels has to do with knowing Captain Wentworth is not as unfeeling towards her as she had supposed before. This goes back to Wiltshire’s argument of Wentworth helping her by taking on the “nurse” role when she requires it, 9 Gared which demonstrates his “warmth,” and Anne’s “renewed” growing attraction for him. Through this consideration for Anne’s well being Wentworth’s icy barrier starts to melt and become less formidable. His sensibility towards her becomes more apparent as he starts to compare her to her unworthy anti-heroine, Louisa Musgrove (Richardson 141). He starts to restudy Anne’s characteristics to determine if he is just by stating she is “altered”. Through bodily contact and Captain’s Wentworth’s chivalrous deeds of saving Anne, there inevitably comes the “arousing consciousness of growing intimacy” between the two. As Anne becomes more aware of her body through her emotional responses: “pain,” “confusion,” and “renewed passion” towards Wentworth, her bloom returns! It happens when Anne and Wentworth’s party goes to seaside Lyme. While they are in Lyme she sees her cousin, who is unknown to her at the time, and he instantly: “…admired her exceedingly. Wentworth looked round at her instantly in a way which shewed his noticing of it. He gave her a momentary glance…which seemed to say, ‘That man is struck with you, – and even I, at this moment, see something like Anne Elliot again’ ” (Austen 70). At the time her cousin “admires” her simultaneously with Wentworth, Anne is “looking remarkably well” because she has “the bloom and freshness of youth restored”. Austen makes her twenty-seven-year-old heroine in bloom again, and the “mortification” of being “unattractive” has ended. Wiltshire believes that perhaps during this scene there is a switch of roles between Anne and Wentworth, where she “improves physically” and he becomes “confused” with his emotions because: “Wentworth is already, perhaps unknown to himself, in love with Anne Elliot, and the incident is only one of a series of moments which confirm his awakening feelings” 10 Gared (Wiltshire 185). Wentworth is becoming “physically” and “emotionally” aware of Anne, especially when she is “exceedingly admired” by another man. This sets-up a rivalry between the men, and Wentworth’s realization that Anne is a sexually desirable woman, who is worthy of any man, and superior to any woman in his perspective. Both King and Young mention Wentworth’s reinstated position as Anne’s suitor. But, since her cousin, Mr. Elliot, is Wentworth’s rival it complicates the plot because: “The triangulation produces the social narrative of marriage, while Anne’s renewed bloom indicates a renewal of their courtship; for the first time since Wentworth left, Anne’s bloom is ‘restored,’ indicating not only her flourishing readiness for marriage but the return, in intention as well as presence, of her lost suitor” (King 130). As soon as Wentworth begins to feel the suppressed love he has for Anne, she is “noticed” by another man; a man more suited to the wishes of her family and Lady Russell. This “renewal of their courtship” connects with the return of Anne’s appearance to what it had been eight years ago when they first fell in love. Now that she is starting to gain her attractiveness and is: “Blown back to life, touched from without to become animated within, Anne is again visible, ‘admired,’ in bloom. She becomes in this momentary glance of brightness the object toward which Wentworth’s consciousness (re)turns” (Young 87). His “consciousness returns” because he is recognizing the Anne Elliot that he saw in their initial courtship, not the “altered” woman whom he resented. Wentworth genuinely loves her and now that she is regaining her looks and is “visible,” he cannot resist his “awakening feelings”. O’Farrell attempts to account for this new phenomenon of rebloom by looking at Anne’s “mortification”. It’s similar to Young’s claim that Anne has been “blown back to 11 Gared life,” but more complex because she asserts that Anne’s “mortification” had a way of being therapeutic and beneficial when she regains her bloom. O’Farrell claims: “Anne’s miraculous return to complected beauty extends to the nature of her reestablished relationship with Wentworth…The source of Anne’s color, like the source of Anne’s pallor, lies in Austen’s own restoration to faith in the material work of mortification. Rejuvenating through mortification the heroine who has sought mortification for its numbing and hardening effects, Austen reveals that heroine to have profited by its quickening pains. Austen’s homeopathic mortification enlists mortification against itself and dispatches Anne’s tired blood to perform its enlivening work.” (O’Farrell 52-3) O’Farrell claims that Anne’s slow “reestablished relationship with Wentworth” helps her rebloom because she becomes happier in his presence. When Anne becomes prettier and noticed by other men, her mortification, or embarrassment, of being noticed by these other men, and especially Wentworth, helps her be “blown back to life,” and makes her “tired blood” pump full and strong in her body. In Wentworth’s presence she feels emotions that were dormant for years. She also feels her sexuality, instead of being an “invisible” corpse-like addition to her family circle. Now that her feelings are “awakening,” she is able to be “enlivening” and “sexually desirable,” as opposed to being “only Anne”. I believe each of the scholars I used made a compelling argument by elaborating on there own different perspectives about Anne’s bloom and rebloom, her body, and the scenes of physical contact. These elements that I focused on are dominant themes in Persuasion and discussed in depth by the scholars of Jane Austen. By focusing on the 12 Gared psychological aspect and the feelings in the footsteps essay, I felt branching out and discussing the body would be a good approach in understanding the novel and Austen’s motive. The emotional affects on Anne’s body, her loss of bloom, and how physical contact between her and Wentworth makes her rebloom forms this “romance,” as Lascelles says, unlike Austen’s other novels. It also gives hope of forgiveness in love. Wentworth, thinking himself alone in suffering and longing for years says to her in a passionate letter, “You pierce my soul. I am half agony, half hope…I offer myself to you again with a heart even more your own, than when you almost broke it eight years and a half ago” (Austen 158). With this beautiful declaration of love and devotion, he writes to Anne that he loves her now more than he ever did. He entreats her to accept him after “eight and a half” years ago, something that would seem impossible in the beginning of the novel. Austen slowly weaves the story in a realistic manner by addressing Anne’s mortification, her unattractive body, Wentworth and Anne’s consciousness of each other through physical contact and Wentworth placing himself in the “nurse” role, and the bloom plot that makes her a “marriageable girl”. 13 Gared Bibliography Austen, Jane. Persuasion. Norton Critical Edition. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1995. Johnson, Judy van Sickle. “The Bodily Frame: Learning Romance in Persuasion.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction Vol. 38.1 (June 1983): 43-61. King, Amy M. “Austen’s Physicalized Mimesis: Garden, Landscape, Marriageable Girl.” Bloom: The Botanical Vernacular in the English Novel. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. 103-131. Lascelles, Mary. Jane Austen and Her Art. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1939. O’Farrell, Mary Ann. “Mortifying Persuasions, or the Worldliness of Jane Austen.” Telling Complexions: The Nineteenth-Century English Novel and the Blush. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1997. 28-57. Richardson, Alan. “Of Heartache and Head Injury: Reading Minds in Persuasion.” Poetics Today Vol.1 (Spring 2002): 141-160. Wiltshire, John. “Persuasion: The Pathology of Everyday Life.” Jane Austen and the Body. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. 155-196. Young, Kay. “Feeling Embodied: Consciousness, Persuasion, and Jane Austen.” Narrative Vol.1 (January 2003): 78-92. . 14